L.A. near settlement to create shelters and clear homeless people off the streets

- Share via

The Los Angeles City Council appears to be heading toward a settlement of a federal lawsuit by agreeing to provide new housing or shelter for thousands of homeless people, while being able to use anti-camping laws to clear anyone remaining on the streets.

The new beds would be spread across the city, based on the number of homeless people estimated to be living in each City Council district in 2020, and could require every council member to find locations for hundreds of new beds.

It’s not clear how much the city might have to spend to fund this ambitious expansion, although it’s a question council members have asked city finance officials. It’s also not clear what the balance would be between permanent housing and homeless shelters, which are designed to be temporary stops.

Spokesmen for both Mayor Eric Garcetti and City Atty. Michael Feuer declined to comment.

Late last month, the City Council deliberated more than four hours in closed session on a deal that would have it create enough shelter over the next five years for 60% of the homeless people in each council district, according to multiple sources familiar with the matter and documents obtained by The Times. It also calls for the “decompression” of skid row by 33%, by attracting people to other parts of the city, to rectify the city’s past policy of containing homelessness downtown.

Council President Nury Martinez said the discussions are “moving in the right direction.”

“L.A. is never going to get out of this crisis unless we’re all committed to this,” she said. “There needs to be full participation from all parties, elected officials, and even residents for us to be truly effective in our goals.”

Late last month, the City Council deliberated more than four hours in closed session on a deal that would have it create enough shelter over the next five years for 60% of the homeless people in each council district, according to multiple sources familiar with the matter and documents obtained by The Times

An agreement does not appear to be imminent, and the talks between the city and lawyers for a group of business owners and residents who filed the lawsuit last year could still break down. Still, most councilmembers seem willing to accept the 60% ratio— modeled after a settlement in an Orange County case overseen by U.S. District Court Judge David O. Carter, who is also in charge of the Los Angeles case. In that settlement, more than a dozen cities agreed to create enough shelter for a specific percentage of the local homeless population. As a result of the lawsuit, shelter or housing was created for more than a thousand people — some in cities that once resisted shelters.

The 60% threshold was based on the experience in Orange County, where the 40% who did not go into shelters or housing “migrated away from the areas, reunited with family, resolved homelessness on their own, entered into substance abuse or mental health facilities, or other unknown result,” according to the proposal.

“There’s a model that Judge Carter used in Orange County, and I see great promise in that kind of a mode,” San Fernando Valley Councilman Bob Blumenfield said.

The proposal would “allow” council members to first clear the homeless camps they find most problematic in their districts as soon as space is available for the people in those camps, and then expand to other parts of the district over time, according to a copy of a proposed settlement, which was obtained by The Times.

At 76, Judge David Carter knows he shouldn’t be on skid row exposing himself to the coronavirus. But he wants more for L.A.’s homeless people.

It was given to the council before its last confidential session and will be discussed again Wednesday when it meets again in closed session.

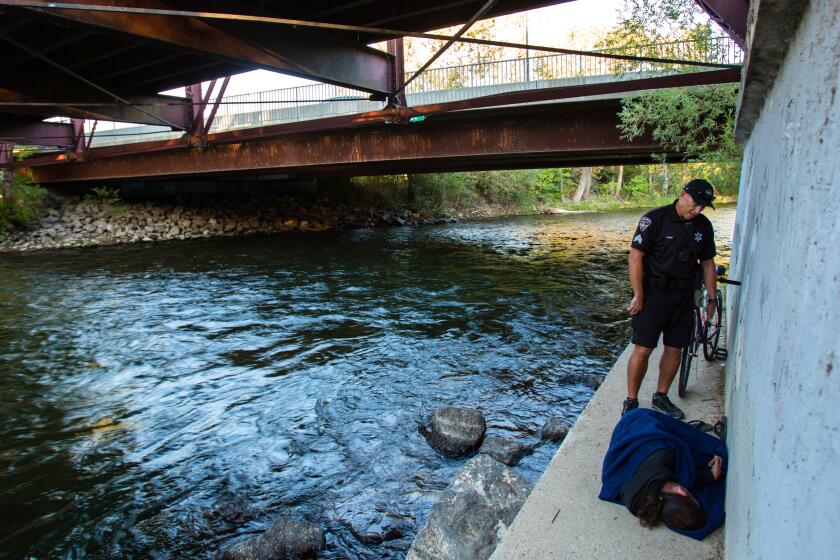

Once the council offices had identified certain “designated areas,” like large encampments under freeway overpasses, outreach would be conducted and a date would be set when people would be asked to relocate.

After an area is cleared, the city’s anti-camping ordinances would be enforced to prevent people from returning, according to the proposed settlement. Enforcement of those laws has been limited by legal rulings that prohibit the ticketing or arrest of homeless people unless the city can provide them an alternative place to live. The proposal calls for a dispute-resolution process if homeless people are unhappy with the housing or services they are offered.

“This lawsuit presents a historic opportunity to make a difference on an issue that is a blight not just on our community, but sort of on the soul of the community here,” said Matthew Umhofer, one of the attorneys for the plaintiffs group, the L.A. Alliance for Human Rights. It is a coalition of business owners, downtown residents and others who are demanding solutions to what they call unsafe and inhumane conditions in encampments.

It is, he added, “the best opportunity the city and county have had for decades to actually resolve this issue and to actually take care of our homeless and unsheltered brothers and sisters.”

Thousands of homeless people living near freeways in Los Angeles County are in line to receive alternative shelter during the COVID-19 pandemic after a federal court judge ordered local authorities to find them housing.

Umhofer, who is with the law firm of Spertus, Landes & Umhofer, wouldn’t discuss the details of the settlement offer or his conversations with city officials, citing confidentiality. The L.A. Alliance filed the lawsuit in March 2020 just before it became clear how serious the pandemic would be and how much of a danger it would be for homeless people.

The 92-page lawsuit cited state and federal law in 14 allegations, accusing the city and county of breaching their duty to abate a nuisance, reducing property value without compensation, wasting public funds and violating the state environmental act and state and federal acts protecting people with disabilities.

Several City Council members interviewed by The Times said they sense a general desire among their colleagues to reach an agreement, but there are still divisive issues that would need to be resolved.

Some don’t like that a deal of such great consequence is being hashed out behind closed doors.

Councilman Kevin de León, whose district includes skid row, said he is concerned that the 60% standard could allow council members whose districts have fewer homeless people and would have an easier time meeting that threshold to drive out their remaining homeless people, who might then head for skid row.

De Leon was on board with the “decompression” of skid row, but acknowledged it is a contentious issue. He said his priority is finding better locations for women, families and children and giving them a chance to be housed and reestablish their lives elsewhere.

“Skid row is no place for women and for children,” he said. “I made it very clear that I don’t want women and children in skid row. I want them in Silverlake. I want them in Echo Park. I want them in Hancock Park. I want them in Sherman Oaks.”

Councilman Curren Price, whose South L.A. district abuts de Leon’s district, said he could support the requirement for new shelter in proportion to the homeless population, but worried about the proposals related to “decompressing” skid row.

“I support providing more resources for skid row,” he said. “Shifting the homeless population from one council district to another is the wrong approach.”

Pete White, executive director of the Los Angeles Community Action Network and an intervenor in the case, said he was unaware of the specifics of the proposal until it was described to him by The Times.

Boise is a midsize city with a manageable homeless population. But it is setting standards for how much bigger cities deal with homeless encampments.

He decried it as “a smoke-filled backroom deal, where property owners and politicians sat around negotiating away houseless people’s civil rights.”

White said the proposal allows too much money to be spent on shelters and in the process criminalizes homelessness.

The terms “would force the city to sink hundreds of millions of dollars into incredibly expensive temporary band-aids that admittedly will not reach all who need them,” White said. “In exchange, the LAPD gets to arrest houseless people and banish them from public spaces.”

While the city is moving toward a settlement, Los Angeles County has gone in the opposite direction, petitioning the court to dismiss it from the lawsuit. Multiple city officials said that even if the city were to agree to a deal, it would require some financial support from the county. Some were leery of the city making a commitment to build beds without first knowing if the county would participate.

The county has participated in prior proceedings in the lawsuit and agreed in a partial settlement to provide services for shelters the city committed to creating for 6,700 people estimated to be living near freeways.

“We need to have the county on board,” Blumenfield said. “They need to be part of this. I don’t think the judge is going to let them go.”

In a motion filed late in March, lawyers for the county asserted that it should never have been named as a defendant.

The lengthy motion argued that the county has aggressively responded to homelessness without any direction from the court by adopting a comprehensive plan, spending hundreds of millions of dollars annually through the Measure H sales tax and developing innovative strategies such as Project Roomkey in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Project Roomkey is a state program that provides temporary funding for cities and counties to rent hotel rooms for homeless people during the pandemic.

Skip Miller, a partner with the Miller Barondess law firm who represents the county, said it decided to contest the fundamental basis of the lawsuit after lawyers for the plaintiffs said that they planned to file a preliminary injunction asking that the court be given more authority over the county’s homelessness response.

The plaintiffs filed a motion for a preliminary injunction Monday.

“Who do you want opining on and resolving who gets housing first, lawyers and the courts?” Miller said. “Or do you want the experts, front-line professionals and county officials, who have more than met their legal obligations in tackling this complex problem? The answer should be obvious”

Both the plaintiffs and members of the City Council have criticized the county’s move to extricate itself from the case, arguing that it is using legal arguments to circumvent a historic opportunity to address homelessness.

“This is much bigger than any litigation tactic,” Umhofer said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.