Why a fight over homeless people could determine how much coronavirus hurts California

- Share via

Despite unprecedented attention and spending on homelessness, tens of thousands of people are still living on the streets of California amid the coronavirus outbreak.

Officials say failing to help them move indoors is a stumbling block in efforts to slow the spread of the COVID-19 virus, as cases across California spike and hospitals are rapidly filling up.

A new study puts the risk homeless individuals face in stark terms: It estimates that nearly 2,600 homeless people in the Los Angeles area alone will need to be hospitalized for COVID-19, and about 900 of them will require intensive care. The data shows how an outbreak in this vulnerable population could strain an already fragile hospital system.

If that many homeless people do indeed stream into local hospitals in the coming weeks, it could lead to increased competition among all patients for beds and ventilators. Officials have said California has far fewer of both than will be needed in coming weeks as hospitals fill up with the sick.

Homeless people, who are more likely to have underlying health conditions and weakened immune systems, often from living on the streets, are at a higher risk for developing severe forms of COVID-19 than the general population.

“It’s a really urgent thing,” said Thomas Byrne, a co-author of the study and an assistant professor at the Boston University School of Social Work.

Far from giving in to such dire projections, state and local officials have started working on ways to quickly move people indoors, though so far the numbers have been small. What Gov. Gavin Newsom billed a week ago as a coordinated effort has in reality rolled out in the same patchwork, locally led approach that has hamstrung solutions to homelessness for decades.

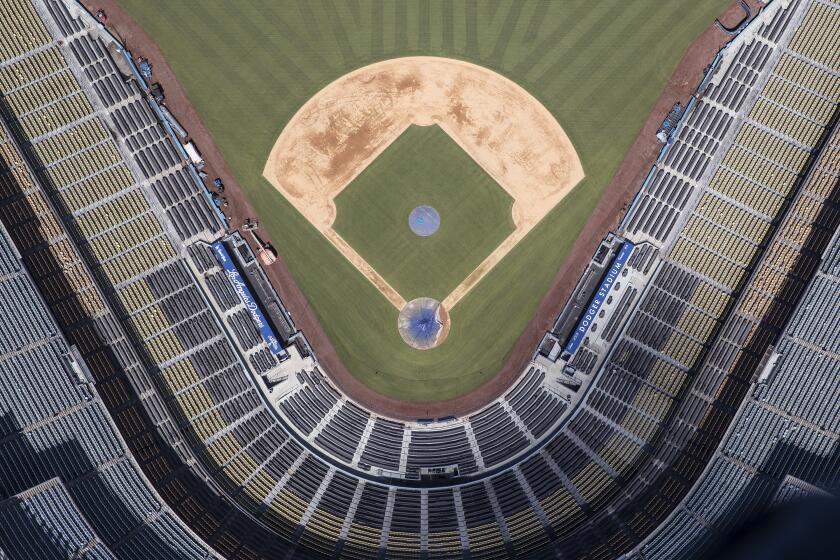

Gov. Newsom has issued a stay-at-home order and all nonessential businesses are closed due to the coronavirus outbreak. So what does it look like outside — from above?

Some cities and counties are rushing to open mass shelters and drawing up plans for how to leave some people outdoors. Others are pinning their hopes on a state-backed effort to secure hotel and motel rooms.

Federal guidance has been confusing on how best to address homelessness during the outbreak and limit the spread of the coronavirus. And some local governments lack the personnel for the massive challenge of moving people indoors quickly.

There also is a growing awareness that many beds and rooms originally planned for homeless people might instead be needed for patients if hospitals are full, or for doctors, nurses and first responders who may be unable to return to their homes between shifts for fear of infecting their families. That is despite the fact that Newsom this week drastically increased the number of hospital beds in the state to handle the expected flood of COVID-19 cases.

Statewide, there is little consensus on the best approach to getting homeless people off the streets.

Last week, Newsom allocated $50 million to purchase or lease hotels and motels across the state for that purpose, along with an additional $100 million in emergency grants.

On Wednesday, he said that there are now 4,305 hotel rooms available across the state, all intended to be run by local jurisdictions.

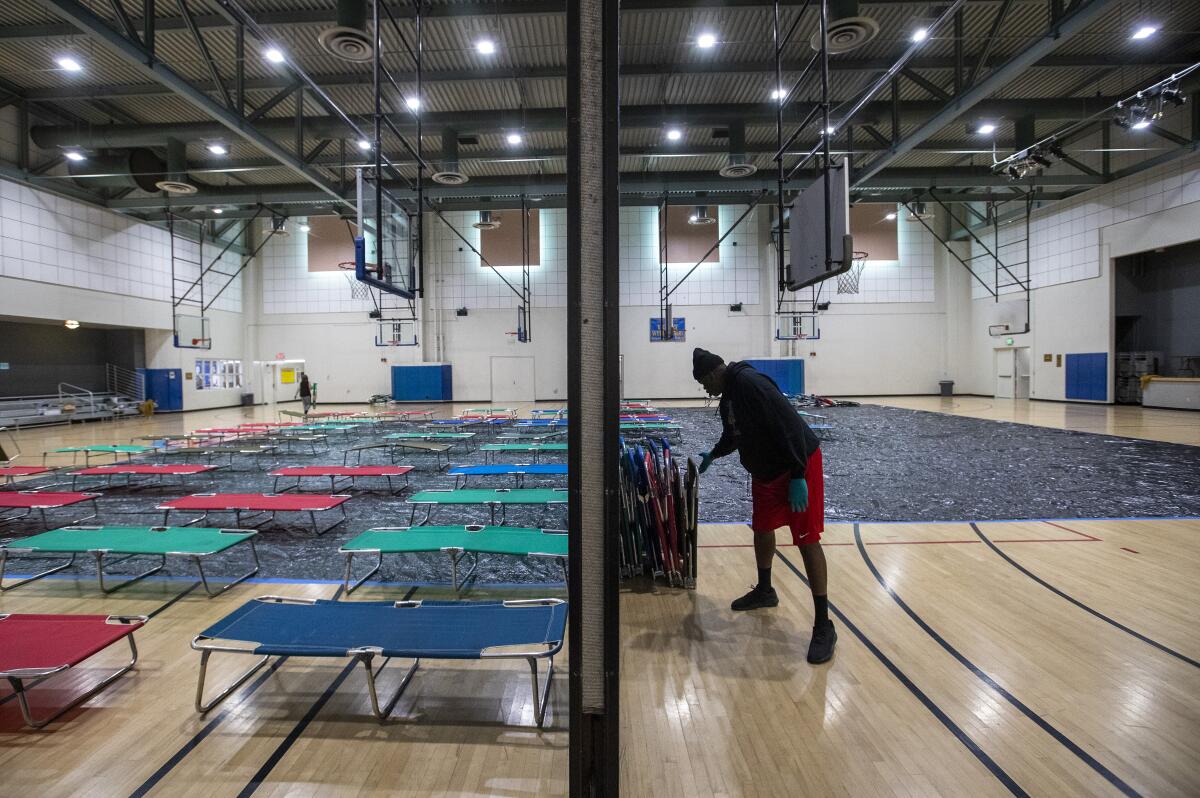

But Los Angeles is relying heavily on new emergency shelters. Some 6,000 beds are planned in city-owned recreation centers.

As of Monday, eight of those shelters had opened with a total of 366 beds. And as of Thursday, most were at 100% capacity, said Heidi Marston, interim executive director of the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority. She said five more shelters were to open by the end of the week, for a total of 13 with 561 beds.

Gov. Gavin Newsom has ordered Californians to stay at home. With businesses and popular destinations closed, The Times’ Luis Sinco documented the surreal scenes.

There has been pushback to using the recreation centers, though, and a fear that they could be incubators for spreading the novel coronavirus among an already high-risk population. While most health experts, advocates and some politicians agree that quick action will require using multiple types of shelter, they say single-occupancy spaces such as motel or hotel rooms are safer.

L.A. City Councilman Mike Bonin said while he’s encouraged by the shelters at recreation centers, he is angry and frustrated that there hasn’t been more movement on the issue of hotel rooms.

“I think, based on the public health advice, that the best thing is for everyone to be housed in a hotel room, motel room or college dormitory,” he said. “That is optimum from a public health perspective.”

Meanwhile, Los Angeles County has compiled a list of 5,000 motel and hotel rooms that could be rented for homeless people who are at high risk for COVID-19, said Phil Ansell, director of the L.A. County Homeless Initiative.

That list has been sent to the state, which will negotiate with the owners of the hotels and motels. It’s unclear how many rooms the state will fund.

The county also is trying to cobble together 2,000 hotel and motel rooms for anyone who needs to be quarantined or isolated because of the virus, not just people who are homeless.

So far, two hotels with 314 rooms are up and running with medical services, food, laundry service and security. Three more hotels with 442 rooms are under contract and are being prepared for patients, said Kevin McGowan, director of the Office of Emergency Management.

“We continue to prepare for additional capacity,” McGowan said Thursday.

San Francisco has embraced the hotel approach in a dramatic fashion. Last week, the county put out a call to see which hotels and motels might be interested in housing people. The rooms mostly would be used for quarantine and for housing those who now live in San Francisco’s roughly 19,000 single-room occupancy hotels, where bathrooms are often shared and conditions are crowded.

Several hotels, including posh establishments such as the Palace Hotel and the InterContinental Mark Hopkins, have offered more than 8,000 rooms for use during the pandemic. Trent Rhorer, executive director of the San Francisco Human Services Agency, estimated the need at about 4,500 rooms. Three hundred have been secured.

About 1,000 of those rooms would be reserved for medical workers and, potentially, to move patients from crowded hospitals if they required a lower level of care.

The residents of San Francisco’s current homeless shelters would likely move to smaller motels, “where we can better provide services that they would need.”

But the city also is planning to open three other shelters with about 2,500 beds, so those who remain in group settings can have more space. They also want to create more space for people who are suspected of having COVID-19 and need to be isolated.

Rhorer declined to say how much San Francisco was willing to pay to rent hotel and motel rooms because negotiations were still underway, but said “literally tens of millions of dollars” would go toward accommodations and meals.

Dr. Mark Rosenberg, an epidemiologist and former assistant surgeon general of the U.S., said that while single rooms are best, shelters could still be useful because it would allow for monitoring, finding and isolating infected people.

“That doesn’t happen when people are on the street,” Rosenberg said.

Staffing shortages

Finding space for homeless people is only part of the holdup, though. There also aren’t enough people to provide services for the newly housed.

“That is the main reason why a whole lot of things haven’t opened up so far,” said Sam Cobbs, chief executive of Tipping Point, a Bay Area nonprofit that works on poverty issues. “It’s not because the places to put people aren’t there. It’s because of the staffing.”

Which agencies should be providing medical care, meals and other services also has been a point of contention.

While typically, county homeless services departments oversee homeless funding and nonprofit partners run shelters, Cobbs and others said the critical nature of the pandemic should mean county public health departments or medical professionals should provide some staffing.

“It’s not a skill thing. It’s a will thing,” Cobbs said. “The emergency relief workers, they’re not interested or willing to staff the shelters because they are saying, ‘Hey, that is not a medical emergency.’”

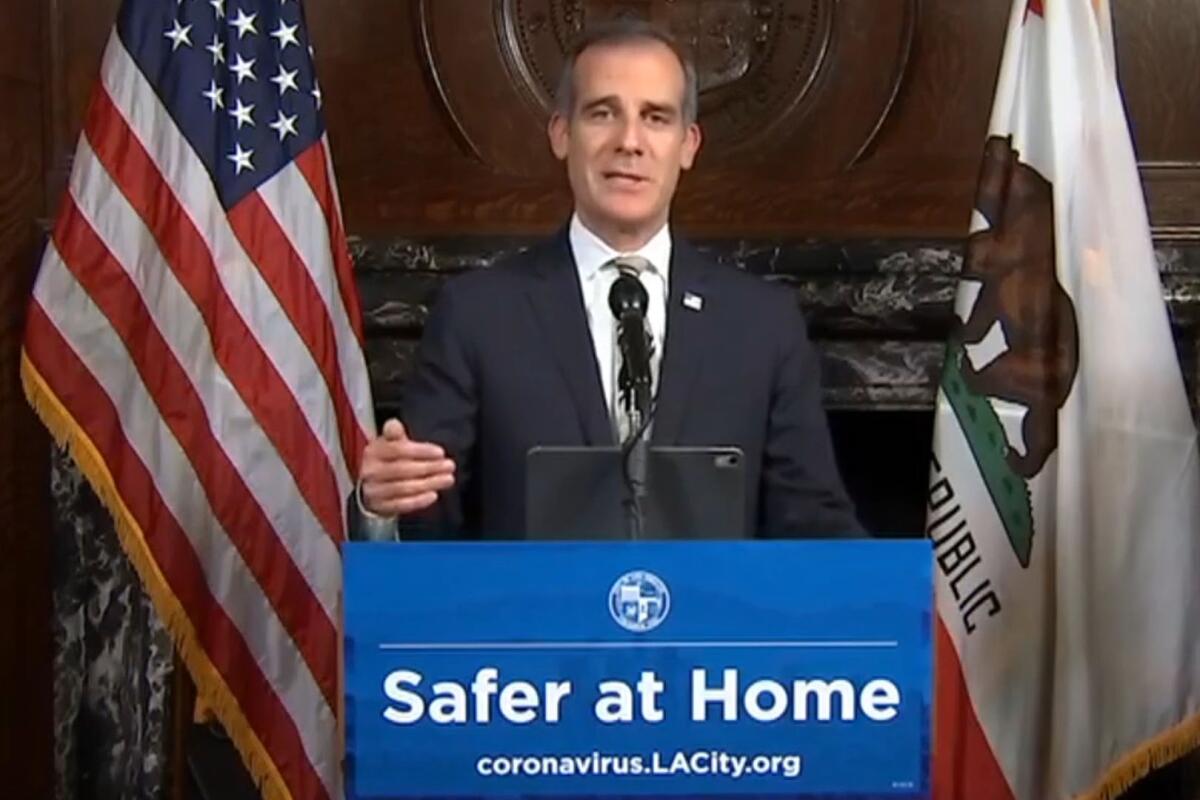

In Los Angeles, Mayor Eric Garcetti cited some of the same concerns.

“You can’t just put somebody in a hotel room,” he said Tuesday. “You have to be able to monitor them and make sure that you can check on their temperature or, if they are symptomatic, you can check health.”

Some cities and counties, faced with staffing limitations, are now planning to leave homeless people on the streets. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently put out revised guidelines, advising local governments not to clear encampments if indoor space isn’t available, and instead allow people to remain where they are with enhanced sanitation services.

“Even if communities are able to offer housing, forcing people against their will into services or accommodations of any kind is simply not an effective approach,” said Barbara DiPietro, policy director of the National Health Care for the Homeless Council. “Trained outreach workers understand how to build relationships and engage people into care — and unfortunately, many communities are having to pull back outreach services at this time, which may leave very vulnerable and isolated people without a trusted source of information and care.”

For those left on the streets, the pandemic has already disrupted daily life and caused a secondary set of problems.

Shaunn Cartwright, an activist in San Jose — where Santa Clara County has announced that at least one homeless person has died from COVID-19 — said the strict social distancing mandated by health officials is making it hard for homeless people to find food and services because many businesses are closed.

“When we went to shelter in place, it took away 90% of the places where they charge their phone — McDonald’s, libraries, Starbucks,” Cartwright pointed out.

Randall Kuhn, a UCLA researcher who helped compile the study on how the coronavirus will affect homeless people, agreed that the shutdown in California and other states has meant that those sleeping on sidewalks are living without the resources they need.

Across the United States, nearly 22,000 homeless people, or 4.3% of the homeless population, could require hospitalization, though researchers say the final number could go as high as 10%. More than 7,000 may need to be placed in intensive care. Researchers estimate that 400,000 additional beds at a cost of $11.5 billion would be required to address the country’s emergency quarantine and shelter needs.

Kuhn said that Los Angeles in particular needs more ways to bring people inside because it’s not a given the outreach workers will be able to continue working on the streets if the outbreak continues.

“The proportion of unsheltered individuals who could legitimately ride out more than a week or two of serious lockdown is probably no more than 10%,” Kuhn said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.