Garrett Eckbo and the art of landscape

The Sidney and Frances Brody estate, an 11,511-square-foot mansion set on more than 2 acres in Holmby Hills, brought together for the first time three Midcentury Modern masters. Architect A. Quincy Jones designed the house, decorator William “Billy” Haines created the interiors, and for the garden, the Brodys chose the leading Southern California landscape architect of the era, Garrett Eckbo. The house is for sale at $24.95 million, but keep clicking to learn why the design collaboration is priceless. (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

Frances Brody maintained one of the most highly valued private art collections, including works by Picasso, Matisse and Alberto Giacometti, many of which were among 56 lots that sold at auction in May for more than $335 million. Fittingly, Garrett Eckbo (1910-2000) viewed landscape architecture as a fine art and looked to modern painting and sculpture, including artists Joan Miró and Naum Gabo, for the forms, shapes and geometries that appeared in his work.

“The way Eckbo planted and grouped plants was transformed,” said Mark Rios, principal of Rios Clementi Hale Studios, an environmental design firm in Los Angeles. “He was more interested in the character and texture of plantings. He would select a plant for its sculptural quality or create mass plantings in a painterly fashion. He redefined the ideas of planting design instead of following the tradition of planting by species. It was less of a garden-y approach.” (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

The entry to the house steps up to bedrooms and down to the entrance of ... (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

... glass openings to a courtyard living area. Of the hundreds of gardens that Eckbo designed during a career spanning more than 50 years, the Brody property remains one of his most exceptional -- and intact -- residential projects. The house required a coordinated effort among the three designers. Eckbo believed that “it is best to plan the whole lot at once as a series of indoor-outdoor rooms” and that “gardens are places in which people live out of doors” -- a recurring theme in books Eckbo wrote on landscape design. (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Here in the courtyard: a fireplace and furniture, just like one would see in an traditional indoor room. (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

“You cannot tell exactly where one person’s work starts and stops,” said Rios, also a former director of the USC landscape architecture program. “Quincy was honestly active with the design of some of the outdoor spaces, like the pool house, and I think Eckbo’s patterning and forms in addition to the landscape probably influenced him, along with the furniture in the atrium and the outdoor furniture that Haines also designed, and how it was all used. It is a wonderful model of collaboration that all of us practicing today want to have, that kind of seamless approach in our work.” (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

Jones created large windows, sliding glass panels, multiple entryways and patios, and vistas from the inside out and the outside in. (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

In seemingly every room, the connection to the outdoors was as important as the world-class art collection that the Brodys maintained. (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

The plan of the house, Eckbo said, “increased the sense of space, movement, and interest” and eased the transition between indoors and outdoors. (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

A lamp design by interior decorator Billy Haines, a key part of the design trifecta. (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

Eckbo’s understated water fountain near the dining room is another integral connection between the interior and exterior. (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

The two terraces in the master suite upstairs appear as floating landscapes that raise the ground plane from below. On the exterior, vertical steel trellises for plants to climb become natural walls -- half architecture, half landscape -- to further define the open and enclosed areas in private and public spaces. (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Another look of how the second floor relates to the first. (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

Stairs leading to the bedrooms ... (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

... and a different view of the courtyard. (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

The master suite has its own living area with fireplace and terraces for sunshine and fresh air. (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

The master bedroom. (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

Another bedroom. (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

Did someone say 1952? In the Brody house, the outdoors were brought inside in many ways. After the completion of the Brody house, architect A. Quincy Jones, landscape architect Garrett Eckbo and decorator Billy Haines collaborated once more for the Gary Cooper house, also in Holmby Hills. Although each designer had his own long and successful career, the three did not share another client like the Brodys. (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

Eckbo taught at USC and became chairman of the landscape architecture department at UC Berkeley. He was especially interested in the social benefits of site planning, anticipating the increased need for smart growth and sustainability. But it is his body of enduring landscape projects for which he remains best known. Eckbo worked with widely recognized architects of the era: Gregory Ain, Pierre Koenig, John Lautner and Richard Neutra, among others. (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

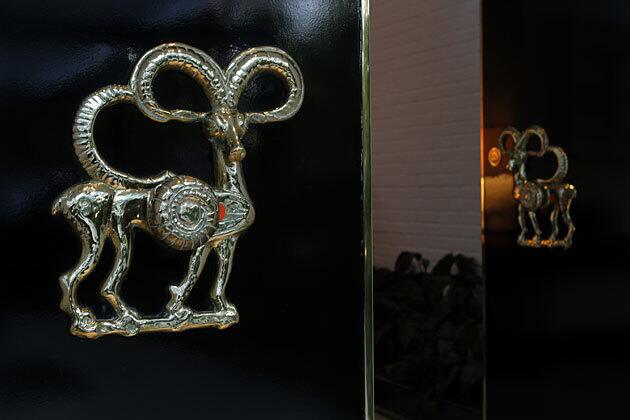

Billy Haines’ elaborate door knobs stood sentry at the front door. After the Brody house, Eckbo was sought for commercial and residential projects alike. He often expressed to clients that a building only exists, visually and spatially, in relation to the surrounding landscape. And the site, as he stated in his book “Landscape for Living,” exists in relation to people. “The building and the site are one in fact and in use.”

MORE

100 California homes in pictures

L.A. Times’ sustainable gardening column

(Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)