- Share via

The smell grabs you first. Barely charred meat kissed by the radiating heat of binchotan charcoal and salty-sweet tare glaze sends out cartoon-worthy wafts of smoke. They lead to the grill where social-media sensation and self-proclaimed “yaki hypeman” — best known as Yakitoriguy — is brushing, fanning and flipping kushiyaki.

Between his frequent pop-ups, his online tutorials and his behind-the-scenes videos of izakayas and other yakitori specialists around the world, Yakitoriguy — who has dropped his given name and insists on his nom de yakitori — is spreading the gospel of Japanese grilled chicken one skewer at a time.

The former Bay Area startup worker now spends his days in front of not computers but birds. He loves that the full circle of his method deconstructs the whole chicken, then reassembles it, bringing it back together for diners, yet another way to educate. Each skewer is a map of how much the bird can vary from piece to piece.

“If someone says something tastes like chicken,” he says, “I always say, ‘Well, which part of the chicken?’”

L.A. is home to traditional yakitori and kushiyaki, as well as modern spins that add California flavor to the beloved Japanese cuisine. Here’s where to find the best skewered meats grilled over binchotan charcoal.

That yaki education for U.S. diners is crucial to Yakitoriguy’s mission. While ramen and sushi have been embraced in this country, true yakitori is harder to find. The traditionally casual form of dining is often found in izakayas or street stalls, typically inexpensive skewers arranged by morsel: Chicken is king, with yakitori options broken down by thigh, heart, wing, gizzard, tail, skin, tsukune (meatball) and beyond.

Kushiyaki, the broader designation of grilled skewers, can mean scallops, beef tongue, bacon-wrapped vegetables or pork belly, plus any and everything else imaginable thrown atop a small grate over binchotan, also known as white charcoal and made from condensed tree logs. L.A.’s specialists — Torihei in Torrance, Torimatsu and Shin-Sen-Gumi in Gardena, Torigoya in Little Tokyo, Yakitoriya in Sawtelle and more — lean casual, though a burgeoning pop-up community that includes private-dining options like Tori! Tory! Toré! and Ryoji Yakitori offers more bespoke experiences.

That’s not to say that yakitori doesn’t have more permanent fine-dining moments in the U.S., as it does in Japan: New York’s Torishin is the first yakitori restaurant to garner a Michelin star in the U.S., while Torien, also in New York, is sibling to Tokyo’s Torishiki and also holds a Michelin star. Both require weeks-ahead — if not months-out — reservations.

“I think there are people who are crazy about bacon, or crazy about pizza, or barbecue or tacos or burgers — all these foods have this cultural following behind it,” Yakitoriguy says. “Yet yakitori, at least in the States, doesn’t. But sushi does. Ramen does. So I felt lonely in the beginning.”

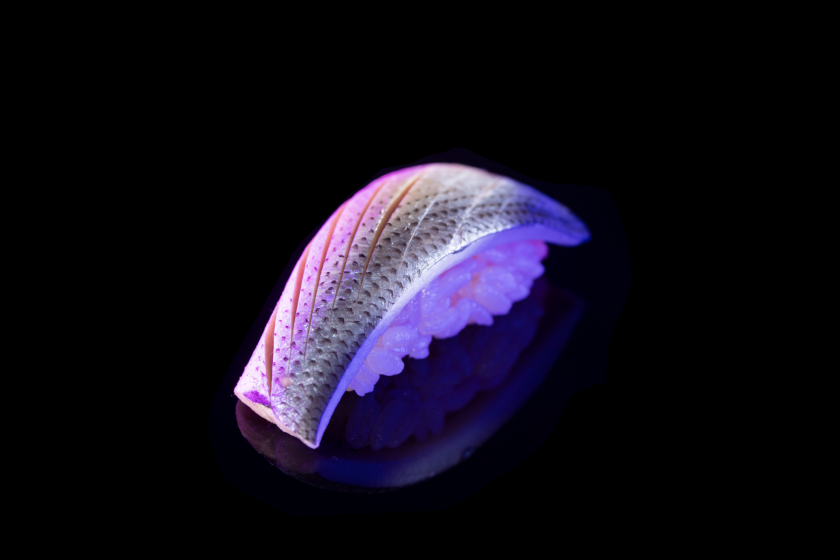

From vegan sushi to hand rolls, modest supermarket sushi to high-end omakase — the greater-than-ever scene in L.A. has what you’re looking for.

He attributes yakitori’s lack of brand awareness partially to a dwindling number of yakitori masters, especially in the U.S.; there are few specialists, and many are older — and not social media savvy.

Keizo Shimamoto, one of the world’s leading ramen authorities and the creator of the viral ramen burger, thinks that one reason yakitori hasn’t made the leap is the labor required: Hours of preparation go into the breakdown of the chicken and the formation of the skewers. But Shimamoto — who first met Yakitoriguy through Instagram DMs and then became a kind of mentor to the chicken-crazy chef — believes that Yakitoriguy is greatly helping to spread awareness of the cuisine in America.

“I mean, he is the resource now,” says Shimamoto, who was the resource proselytizing ramen a decade ago. “If you want to learn how to break down a chicken, you can go to YouTube and he shows you how to do it step by step. The funny thing is, I invited him to my daughter’s birthday party. My daughter’s friend’s parents that I’d never even met, when Yakitoriguy walked in, were like, ‘Hey! You’re Yakitoriguy!’”

The social media star’s YouTube channel, with tutorials and restaurant visit videos, goes out to nearly 38,000 followers, while his Instagram, clocking nearly 80,000 fans, provides behind-the-scenes looks at his pop-ups. His TikTok channel followed with a goal of tapping into a younger audience; since 2021 he’s grown that channel to more than 109,000 followers.

“If there are 100,000 people right now on social media, that means at least 100,000 people know what yakitori is,” he says. “When I started, a lot of people that I met on the street didn’t know what yakitori was; they thought it was teriyaki chicken. That’s like saying, ‘Is ramen just noodles in soup?’”

The biggest change, he notes, has been the recognition: People sometimes approach him both abroad and locally in Japanese grocery stores and when he’s dining in a yakitoriya or izakaya in Japan. That fame has also brought behind-the-scenes access to restaurants.

“They’re very eager to show me,” he says. “They know that I’m going to share their shop or their craft to the world, so they’re actually very happy that there’s someone who’s going to help share their story or their technique. Even in Japan, a lot of customers go there to just eat and aren’t asking questions.”

And yet beyond his online persona, Yakitoriguy is an enigma.

The chef withholds his given name from the public due to a privacy and safety concern regarding a former work acquaintance. But his origin story is unambiguous: He was born in Sapporo, Japan, with Japanese as what he characterizes as both his first language and first culture. At 5 he and his parents moved to West L.A., where he spent weekends visiting the Japanese Buddhist temple, and in Gardena and Little Tokyo, where he experienced Japanese American culture for the first time. He attended college in Santa Barbara, which proved to be an eye-opener: He was raised by parents who don’t drink, and bar culture was a colorful new world for him.

Japanese yakitori. Middle Eastern kebab. Argentine and Chilean asados. Thai satays. Korean barbecue. All contribute to the great cacophony of how we cook with fire in Los Angeles.

“That sort of drinking-dining culture became my favorite,” he says. “This became my Buffalo Wild Wings: Happy hour was not nachos and sliders and fried wings; it became grilled wings and Japanese drinks.”

He went on to work in tech startups until his hobby grew into an obsession, setting him on the path of the chicken. Beyond yakitori — his relationships, other hobbies, even the city he calls home — is harder to glean. But the mysterious nature of Yakitoriguy works for his mission: Removing personal details about himself makes for a clear educational purpose and message.

Pay no attention to the man behind the yakitori. Keep your eyes on the bird.

He does reveal one turning point: when he told friends around a campfire that his 2018 New Year’s resolution would be to learn yakitori — not to become an authority, but simply to grill for himself.

The first thing he did was search on YouTube: “How to make yakitori?” The results, he says, were dismal. Most videos featured food bloggers cooking skewers slathered with teriyaki sauce, not traditional yaki brushed lightly with or dipped into tare sauce. Typing in Japanese yielded more results, but the videos were crudely edited and not too user-friendly. He’d found his niche.

Around Month 2, he became obsessive. He tested dishes for friends and began a private, ticketed dinner service at $50 per person in March 2018 — what his tech start-up background would refer to as proof of concept. More friends wanted a seat, resulting in a secret pop-up in his Bay Area studio every weekend, booked a year out. By September of that first year he’d quit his job to study in Japan, finding mentors and building community through Instagram and local restaurants. He tried to visit Japan twice a year; during the pandemic, when the country closed its borders to international travelers, he dreamed of his return and, last September, visited for six weeks — hitting 26 yakitori shops, taking video footage and doing interviews. Most still haven’t been edited and uploaded to his channel.

His tare recipe, along with all of his other know-how, is on full display for free on his YouTube channel and social media. After all, he says, his own mentors and other chefs he’s encountered have been open with their recipes and tips — why gatekeep? A public Amazon list he labeled “Getting Started” includes items every yaki novice could need: budget-friendly binchotan, wooden dowels, ube and shiso pastes, commercial-grade bins for marinating, a range of grills, paddle fans to clear the smoke, pastry brushes for applying tare.

The tare is crucial to yakitori, at once a glaze and a seasoning, never gloopy or heavy. It is often a blend of soy sauce, sugar and sake or mirin, with the sugar adding sweetness and caramelization on the grill. It differs from teriyaki sauce as it’s not simply a glaze but what Yakitoriguy calls a vessel: In Japan, skewers already mostly grilled are dipped into large clay jugs of the tare sitting next to the grill. Every time smoky chicken fat is dipped into the jug, the tare takes on more nuance, building flavor like a mother sauce. Often they’ve been kept going for years, some for as long as a century.

“Now, does 100-year-old tare taste like 100 times better than 1-year-old tare? No, not really,” he says. “But it’s bragging rights.”

At Gardena’s Torimatsu, one of Yakitoriguy’s favorite L.A. restaurants, Shoji Ishikawa uses a thick tare more than 30 years old — and once guests have lifted their skewers from the serving tray, the staff brushes the excess left on the platter back into the large jug, never wasting a drop. Yakitoriguy’s own tare, while only 5 years old, involves a kind starter aged 39 years from a shop he worked at, as well as another former employer’s, which was only 2 years old.

“It’s just the spirit of the product that’s in there at this point,” he says. “It’s my baby. I’d never want to lose it.”

Once, when he was moving apartments, he spilled a fourth of his tare — which is why he always keeps a backup in his fridge. In late July he flew his tare to Seattle for a pop-up, storing it in two screw-top water bottles and hoping for the best. (His 24-inch grill fit into a rolling bag, all its parts Saran-wrapped to itself for organization.)

A spring pop-up saw the yakitori evangelist arriving at the kitchen of Little Tokyo’s Japanese American Cultural and Community Center at 8:45 a.m. and prepping for roughly nine hours. To break down chickens so precisely and cleanly, he uses a small arsenal of knives, and sharp ones at that. He designates his “chicken cutting knives” almost exclusively to working with poultry to keep them in top form, slicing through and around skin, tendon and cartilage.

On any summer weekend in Los Angeles, parks are filled with amateur grill masters and chefs cooking up traditional and nontraditional global feasts.

The sharp point of the triangular, stiff honesuki knife, specifically designed for chicken, allows him to maneuver between the muscle and the bone. The garasuki, longer and thicker, allows him to cut easily between bones. “You need the cleanest cut of the chicken to be able to then get the cleanest meat, you need the cleanest meat to yield the cleanest skins,” he said. “Every step matters. It’s a process.”

Especially in the U.S., where yakitori is not as ubiquitous, specialized parts of the chicken aren’t often sold individually; to acquire the oysters, the arteries, the tail, the shoulders and other cuts he opts to break down whole chickens for his pop-ups, with each guest eating through half of a chicken by evening’s end. Japan’s yakitori chefs are lucky, he says: They can simply call their providers and request bags of chicken tails.

Out of necessity he began serving his own kind of signature skewers, combining pieces: The tail, for instance, includes a soft bone running through the end, with meat on either side, which he separates and serves with smaller pieces from the thigh so that two diners can receive tail meat from the one chicken. It takes him three to five minutes to break down a chicken now without rushing, but when he started it took him around 45. Some of his novice YouTube subscribers comment that breaking down a bird and assembling the skewers can take them upward of three hours.

Extra pieces, such as carcasses, removed bones, necks and membranes, are added to chicken stock that’s been on his menu for five years and simmers on the stove with kombu, onion discards from negima skewers and other aromatics, to be served toward the end of the night with a grilled onigiri, the rice just barely charred — though at one pop-up, he ground the neck cartilage and shoulder, then stuffed it into a deboned chicken wing and grilled it together.

At the JACCC, Chris Ono, who runs Hansei restaurant within the cultural center, is helping Yakitoriguy break down chickens and lending his team to do so too. It’s their first time cooking together, slicing in tandem, though they’ve known each other since high school.

“I like asking him a lot about grills because I’m not really into yakitori as much, but I love it,” Ono says. The knowledge exchange works both ways: While Ono asks for advice on grilling and skewers — especially for the launch of his own kushiyaki pop-up hosted at Virgil Village wine bar Melody — every so often the yakitori specialist will pick Ono’s brain for tips on working with fish.

That collaborative spirit is endemic to yaki chefs. Perhaps it’s the tie to camaraderie and drinking culture, but in Japan the accessible, affordable nature of the dish has brought together hundreds of chefs for a number of yakitori-focused festivals — a network of professionals happy to share their knowledge with one another and, thanks to Yakitoriguy’s newfound spotlight, more curious diners and home cooks alike.

He hopes that this community will more readily spread to America, but in the meantime, he hopes to take over a local yakitori spot for an event where he isn’t even cooking but emceeing the restaurant’s usual chef, explaining to diners what techniques are being employed and what each course entails — an excuse to hype up another yaki master.

On a busy night at Torimatsu, Yakitoriguy sits against the far wall at one of the restaurant’s hotly requested counter seats. He orders rapidly in Japanese: a range of yakitori and kushiyaki, a preference for scallion salad and, later, shochu on the rocks and a small bowl of chicken sashimi.

He doesn’t have a favorite skewer. It’s a yakitori chef’s job, he feels, to take every cut of the chicken, to give it use and purpose and appeal — even to those who might not normally order it. Partially, it’s due to innovation: If the breast is often too dry, it could become juicier when wrapped in skin or wedged between yuba or fat before it hits the coals. Liver, when cooked expertly, has a tendency to become creamy and lose its overt iron taste.

He watches Ishikawa, rapt and captivated, just as his own followers and diners tend to stare at him, wide-eyed and eager, during his own pop-ups.

“I think my whole romanticized fascination is with any craftsman from Japan — whether they’re making swords or this — because they’re doing it for life,” he says. “There’s something about repetitive skills. Through repetition, knowledge and experience that builds up, kind of like the tare: just over time.”

Like his own tare, built on contributions from the masters who came before him, it’s a fascination layered with information and aid from his global network of fellow yakitori evangelists. Maybe, he says, he can be that authority and provide guidance to a future yakitori chef, keeping the specialty — and the tare — going for generations to come.

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.