- Share via

The laid-back enclave of Ojai, tucked within the Topatopa Mountains some 80 miles north of Los Angeles, boasts the unofficial motto, “There’s nothing to do in Ojai, and not enough time to do it.” For some culinary enthusiasts, the phrase “nothing doing” has pretty much summed up the restaurant scene of this tiny tourist town, but many locals prefer it that way — which may account for the “Keep Ojai Lame” bumper stickers seen here and there.

If the gastronomes are real old-timers, their touchstones may be the Ranch House, which grew out of a vegetarian boarding house in 1950 and is still in operation several iterations later, or Suzanne’s Cuisine, a mom-and-daughter mainstay that persevered for 25 years but closed in 2017.

On the outskirts of town, the Ojai Valley Inn will celebrate its centenary next year. The upmarket destination resort has made a national splash, enlisting Nancy Silverton to curate seasonal events like last November’s sold-out, beef-centric dinner prepared by celebrity Tuscan butcher Dario Cecchini for $500 a pop (plus tax and tip). But if you make a weekend trip to Ojai and stay in another hotel or one of the many Airbnbs in the area, the guest-focused inn probably will not be an option.

Now a handful of young restaurateurs have set up shop a few blocks from one another in the small downtown, invigorating the dining landscape. Three of the four new restaurants make their own sourdough, which prompted one customer to suggest christening the area Ojai’s Sourdough District.

The entrepreneurs, all of whom launched during the pandemic, quickly formed an alliance. “We reach out to one another for a bundle of aprons or a bag of flour,” said Meave McAuliffe, chef of Rory’s Place, a farm- and ocean-to-table collaboration with her younger sister, Rory. “On our respective days off, we eat at each other’s establishments. It’s very sweet.”

Meave and Rory grew up near the beach in Venice and spent their adolescence helping out in their mom’s Santa Monica bakery, Odeon Breads and Pastries. The family summered on the tidal flats of Cape Cod, where the girls harvested and shucked oysters. Meave went on to become head pastry chef at Gjelina in 2009 and ran the kitchen at Saltwater Oyster Depot in Marin County. While she put together a project of her own in upstate New York, Rory, a front-of-house veteran, was imagining a wine pub in L.A. called Rory’s Place. “I thought it was a great name,” said Meave. “I’d never want to have a restaurant named after me, though.”

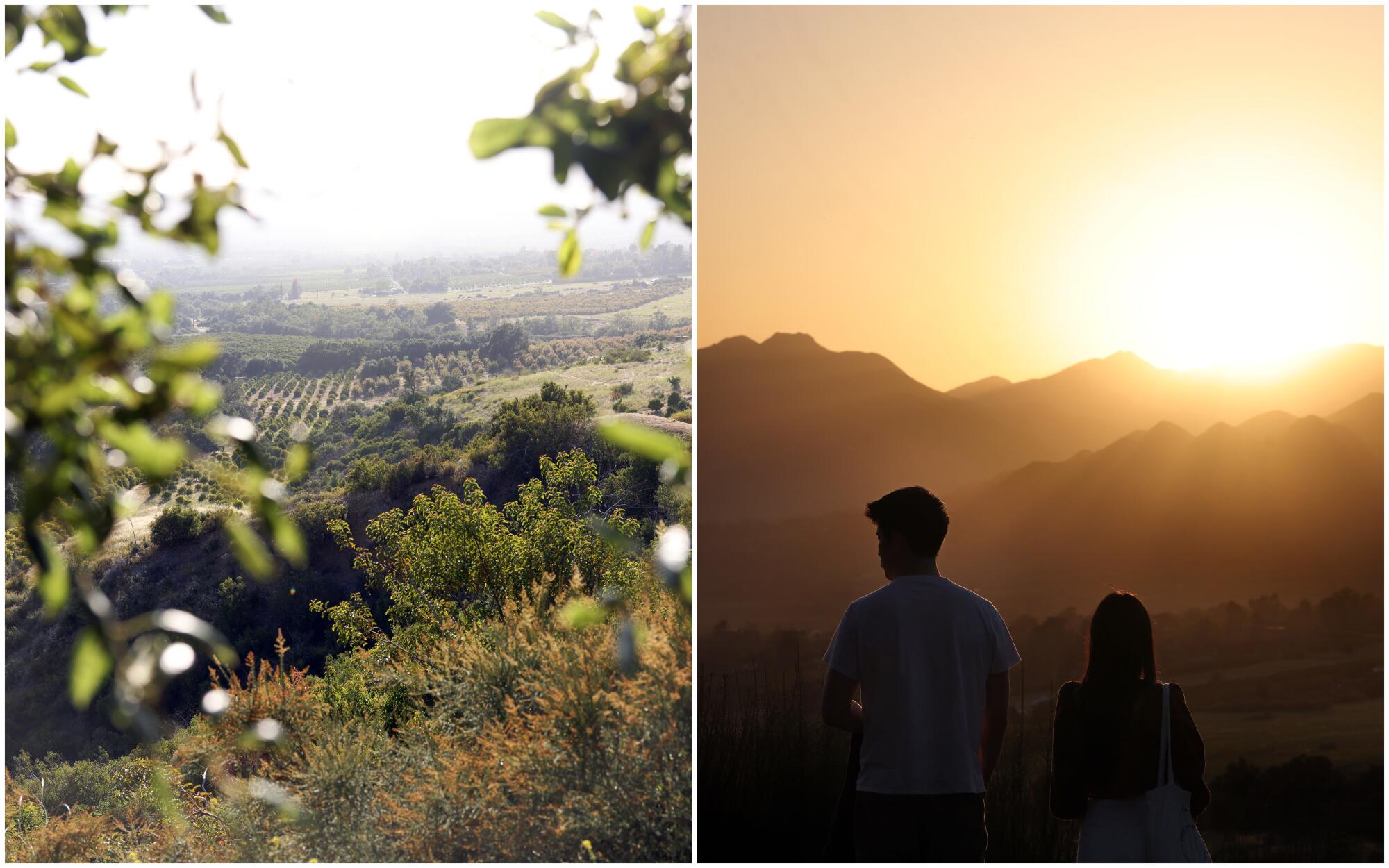

Their plans coalesced in Ojai, which had long enchanted them with its Meditation Mount, its groves of sugary Pixie tangerines and its otherworldly “pink moment,” a fleeting period before sunset when the peaks that frame the northern edge of the valley take on a pastel glow. “We wanted to add a truly elevated dining experience to the local mix,” said Meave. “Something personal and thoughtful and surprising and playful. Something people would travel here for.”

Though Ventura County is rich in farming and fishing traditions, some Ojai bistros don’t typically procure raw ingredients from local purveyors. Most restaurants exist on such thin profit margins that they can’t afford to buy local. There’s also a problem of seasonality — the menu has to reflect what’s available.

“As we formed partnerships with farmers and fisherfolk in the region, we realized that their bounty was being underutilized,” said Meave. “We brought a new approach to eating in Ojai — an old approach really: eating the food that’s produced close by.”

Beside crudos, gem salads and winter squash tempura, Rory’s offers such inventive takes as halibut agua chile with passion fruit, and agnolotti stuffed with bottarga and spiny-tail lobster. Among the fun twists on old standards are broiled oysters in fermented chili butter, and a half-chicken that’s been brined, air-dried, seared, roasted with escarole over a wood fire and dotted with blackberries.

While Rory’s rough-hewn, Craftsman-era space adjoins the theater that in 1914 showed Ojai’s very first movie (“Valley of the Moon”), the Dutchess occupies the building in which baker Wilhelm Koch — who in 1916 won $500 in a wheatless-bread-making contest and legally changed his name to Bill Baker — created a one-ton fruit pound cake decorated with 2,000 frosting roses and 1,000 birds. Later in the century, the facetiously named Ojai Men’s Prostate Club met there every morning for coffee.

Named for Baker’s original oven, whose bricks were repurposed last year as the backyard patio, the Dutchess was touted by Vogue — which called it “a chic new all-day restaurant and bakery” — even before opening day. The proprietors are Zoe Nathan and Josh Loeb, whose L.A. establishments include Rustic Canyon, Milo + Olive, Tallula’s and Huckleberry. At the start of the pandemic, the couple moved their family to a 3½-acre farm in Ojai. “We had no intention of opening another restaurant,” said Nathan.

By day, the Dutchess is a bakeshop run by local sourdough sensation Kate Pepper and Kelsey Brito; by night, it’s a Burmese-themed operation presided over by chef Saw Naing, a onetime heavy metal musician who emigrated from Rangoon, Myanmar, to L.A. in 2007 after repeated jailings for the political content of his songs. A decade later, Nathan made him executive chef at Tallula’s.

One day last spring, Nathan was giving a tour of her new farm to her old friends Pepper, Naing and Milo + Olive pastry chef Kelsey Brito. When she got to the pigpen, she confessed, “I can’t bring myself to kill my pigs to eat them, and it’s not because I’m Jewish.” Suddenly, she had a vision: “Let’s start a restaurant that’s a bakery with Burmese food in this Jewish lady’s house where you get a hug, and her mom is liable to walk in any second.”

“Cool!” chorused her three guests.

And on that slender column, the Dutchess was born.

Just inside the kitchen door, savory smells waft with the heat — cloves, turmeric, tamarind, cinnamon, curry leaf and fenugreek: a catechism of Burmese cookery. Naan dough goes into a big, black tandoori oven thin and flat and round as a cardboard moon; 30 seconds later, it comes out puffed up into a toasty brown pillow fat enough for a pasha’s divan.

Though less adventurous dinner guests can order a flat-iron steak or quail tikka masala, the most popular dish is a Naing-Pepper creation, the biriyani (chicken cooked in spiced basmati rice and cashews) encrusted in puff pastry. Brito is responsible for the passion fruit lassi pie and rose geranium kulfi, a frozen fever dream of cardamom and pistachios.

While the Dutchess is an outpost in a vast hospitality empire, Pinyon is a pioneering collectivist experiment. The pale, long-haired staff of this pizzeria, natural wine store and sandwich shop — it’s the only spot in town that serves hoagies — tend to look like denizens of Middle-earth who’ve been locked away from sunlight. Credit the Pinyon business model: Every employee gets a cut of the profits and is paid the same wage — $20 an hour — regardless of position. “We’re trying to empower people to take ownership of their work,” said pizzaiolo Jeremy Alben, who launched Pinyon with his friends Tony Montagnaro and Sally Slade.

The son of a poet and a UCLA law professor, Alben is a protégé of the Swedish chef Magnus Nilsson, whose New Nordic ethos emphasizes locavorism. After finishing high school, Alben apprenticed at Nilsson’s fabled two-Michelin-star restaurant, Fäviken, in the wilds of subarctic Sweden. When not foraging for moss, juniper and pine needles, the teenager learned to ferment moose sausages and fry breaded pig heads on a skewer. Neither is featured on the menu at Pinyon, where the most outré topping on the five weekly sourdough pizzas is pureed pumpkin.

Alben polished his pie-making skills at Roberta’s in Brooklyn and Culver City, and mastered them with Montagnaro, whose family owned two pizza parlors in New Jersey. They hope the chief virtue of Pinyon’s pizzas (think asparagus, lamb-cetta and local goat kefir) is what Neapolitans call digeribilità (digestibility), an endearing term for easy-to-eat pies that your body welcomes with seeming effortlessness.

That aspiration chimes perfectly with Ojai’s harmonious vibe. Ashton MacSaylor, a teacher at the local Krishnamurti school, observed: “Seating at Pinyon feels like being served gourmet, multicultural food in your best friend’s backyard. If those friends were hobbits.”

The name Ojai is derived from the Ventureño Chumash word for moon. Yuya and Asaka Ueno, the Japanese husband-and-wife team who run Izakaya Full Moon, attribute the birth of their first son, Kirato, to the gravitational pull of Earth’s only natural satellite. On a moonlit night in 2011, during her first visit to Ojai, Asaka was pregnant, and when her water broke, she calmly drove to UCLA Medical Center in Santa Monica and delivered the baby. “It was the magic of the moon,” she said.

Six years ago, Asaka and Yuya opened Cagami Ramen in Camarillo. Their unassuming Ojai cafe — five patio tables and a seven-seat sushi bar hidden behind Magic Hour, a specialty tea emporium — specializes in authentic, deceptively simple bar snacks like tai chazuke (grilled rice balls doused in snapper broth), barbecued skewers and karaage fried chicken. Yuya’s recipe for white corn tempura comes from his hometown on the rural Bōsō Peninsula; the goma kampachi (amberjack sashimi marinated in a tahini-esque sauce) is a specialty of Kyushu, the island on which Asaka was born. “In Ojai, we feel part of a small community of restaurant owners personally looking after the quality of experience of each guest,” said Asaka.

Anna Thomas, author of the cookbooks “The Vegetarian Epicure” and “Love Soup,” is a longtime resident of Ojai who has viewed the dining scene as lacking. “Ojai has always had a great food culture,” she said. “But the great food hasn’t been in restaurants; it’s been in the farmers markets and people’s homes.”

Now, to Thomas’ delight, great things are happening in the town that takes pride in being lame.

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.