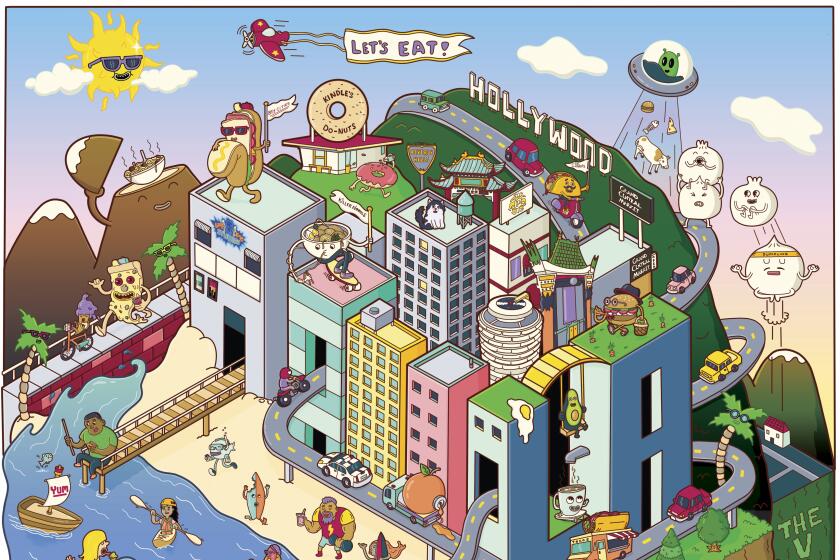

Food writer Eddie Lin pays tribute to a chef who embraced the multiethnic mixture of L.A. after emigrating to Baja.

- Share via

I first met chef Lupe Liang in June 2010, when I was invited to emcee the very first Chinatown Summer Nights event. It would be a big community party with food, music and art. He and I helped plan the culinary stage programming, and I had some preperformance jitters.

“Don’t worry,” Lupe said to me with a gleam in his eye. “I cook something good.”

For much of the evening, the audience was sparse, most opting to hang out across the street at Central Plaza where there was a DJ, bar and dancing. However, once Lupe set up for his cooking demo, a decent-sized crowd started to gather.

His virtuosity with a wok was legendary. With a flick of his wrist, he’d launch chunks of orange chicken into the air like a flock of birds and then catch every morsel without a single casualty.

People gasped in awe with each toss of the wok. He relished the response. The crowd’s enthusiasm relaxed me; Lupe had the demo under control. “OK, Eddie?,” he’d smile at me, knowing the answer was a resounding “Yes.”

After Lupe finished cooking, volunteers passed samples of food to the crowd. The audience couldn’t get enough of it. The delight on his face was priceless. Cooking was in his blood. He had cooked since he was 7 years old. Chef life was the only life he knew.

Liang “Lupe” Ye Ning, proud owner of Hop Woo BBQ & Seafood in Chinatown, beloved husband, father, brother, chef, captain of his kitchen crew, honorary Mexicano, son of Chinese farmers, pillar of his community, is now gone.

He was 61.

The chef was also my close friend and, to me, the embodiment of Chinatown and, by extension, the best of L.A.’s multiethnic ferment.

Lupe Liang, along with his wife, Judy, both from Guangdong, China, ran their restaurant for roughly three decades. Chinatown denizens respected Lupe, Judy and Hop Woo, and visitors considered the Liangs’ restaurant to be among Chinatown’s most popular attractions, like the twin dragon gateway on Broadway, or Central Plaza’s lucky wishing well.

With its roast ducks dangling in the window, hanging lanterns, laughing Buddha at the door, the restaurant could be lumped among many Chinese restaurants of its kind in L.A. or anywhere else in the country. But Lupe’s was extraordinary, and as I got to know him better, I had to let other people know. I began writing about Hop Woo.

The Hop Woo BBQ & Seafood co-founder is survived by his wife and two daughters, and his Chinatown restaurant.

I lived in Chinatown as a child, playing tag at the Alpine Recreation Center, attending kindergarten at Castelar Elementary School and making wishes at the wishing well. On Sundays, my father treated me to a bowl of wonton noodle soup at the old Mayflower restaurant. This was our ritual and one of my most visceral food memories from childhood. Soon after, my family left Chinatown for the suburbs in search of a better future. This was the way of the immigrant in L.A.

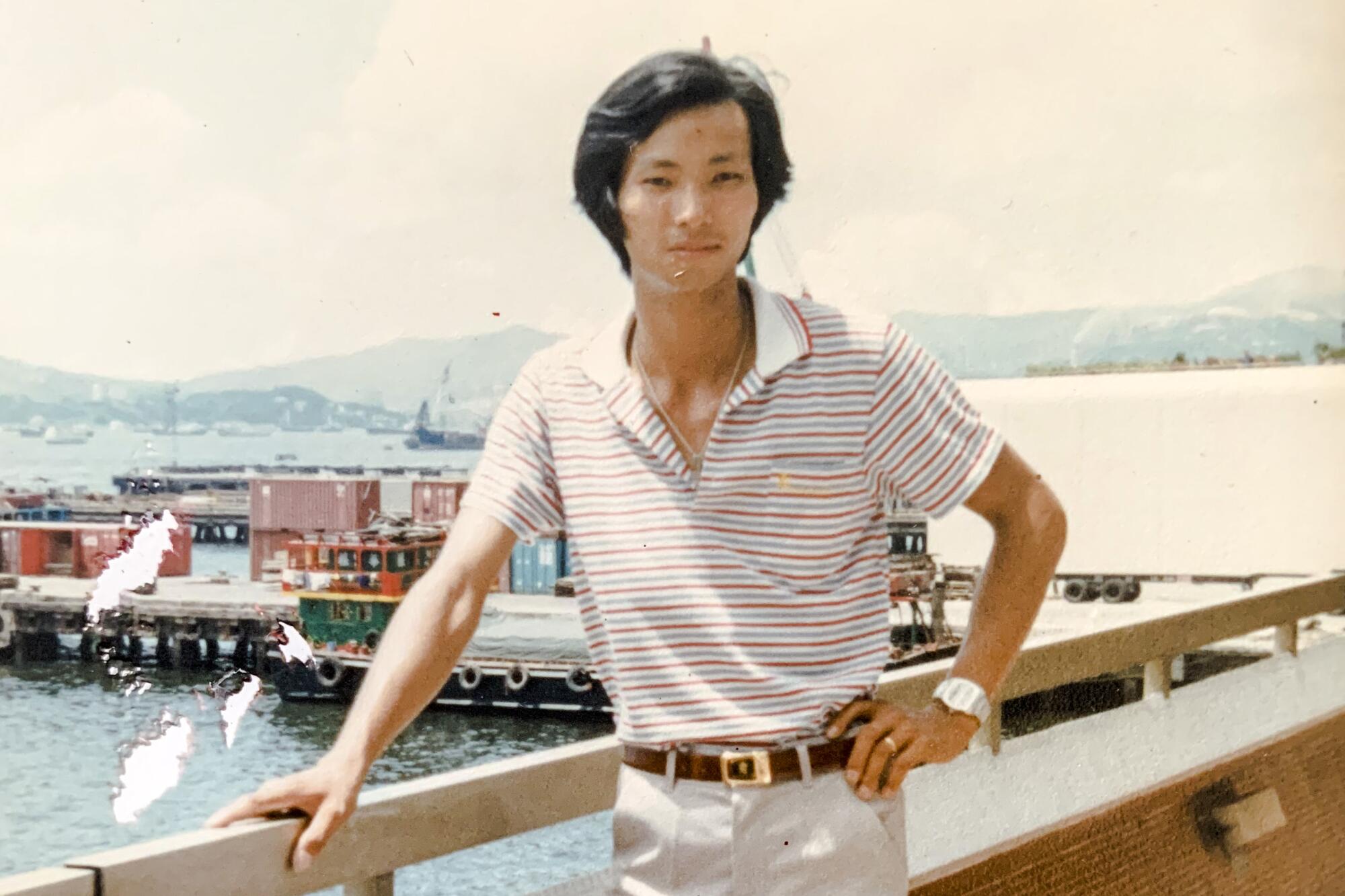

Lupe and Judy came to L.A. by way of Mexico. The two met when Judy was vacationing at Rosarito Beach and Lupe was working at his brother’s Chinese restaurant nearby. Lupe had been working there since 1978, the year he emigrated to Mexico from Hong Kong, his home at the time. Lupe lived in Mexico long enough to become fluent in Spanish and adopt the name Lupe, short for the name Guadalupe.

By the ’80s, the Liangs had arrived in Los Angeles, and by 1993, they’d own Hop Woo, a tiny eight-seat hole in the wall serving Cantonese cuisine. The couple would later transform it into a larger, more appealing restaurant that still sits at 845 N. Broadway.

During my years away from L.A., I’d every so often visit my old Chinatown neighborhood to soothe pangs of nostalgia. One day I returned to L.A. to live, this time with a family of my own. I didn’t reside in Chinatown, but now I visited more often and brought my family with me.

Lupe and I would present many more cooking demos together in years to follow. We were a team. I’d share the stage with Lupe, and occasionally Judy, who was his partner in everything and a constant presence as Hop Woo’s front of house. As soon as his demos ended, Lupe and Judy rushed back to Hop Woo to meet the throng of hungry audience members who wanted more of Lupe’s food.

A friendship blooms

As a food journalist, I’m expected to be unbiased and objective, as it should be. But there are people I meet who will challenge this dispassion with their humanity, kindness and decency, and you can’t help but like them. Lupe was one of those people.

Whenever I’d come into Hop Woo alone for a quick bite, Lupe never needed to ask for my order. Magically, a bowl of wonton noodle soup with beef stew and tendon appeared before me — the hearty soup that was my Chinatown childhood in a bowl. I shared with him the story of my comfort food early on in our friendship, and he never forgot how important that humble dish was to me.

My daughters practically grew up at Hop Woo. I have photographic evidence of their growth from photos of them posing next to the 3-foot-tall laughing Buddha statue at the restaurant’s entrance. In each photo they gained height on the Buddha. When I see my two daughters through Hop Woo memories, I can’t help but think of Lupe’s two daughters, Mary and Kelly, and how they’ve lost their father far too early. Too soon.

I’ve brought my parents, my kids, my life partner, my siblings, all of my closest friends, food writers and so many others to Hop Woo over the years. In each of those moments, Lupe never failed to greet and treat everyone like family by making a meaningful connection and offering his disarming smile. “Don’t worry, I cook something good,” he’d say.

Then came the feast.

Lupe had been a part of my family’s Thanksgivings and Christmases for more than a decade; we’d head to Hop Woo to pick up our Chinese turkey and side dishes like beef chow fun and roast pork. I’d be sure to send him a family Christmas card every year (and I don’t send out too many of those). We also rang in both Western and Lunar New Year with Lupe’s food as the centerpiece of the celebration, making sure we ordered all the good fortune and long life dishes, such as whole steamed sole or yi mein with XO sauce.

We celebrated birthdays and other special occasions there too. One particular Valentine’s Day dinner I experienced at Hop Woo involved a unique aphrodisiac soup made with Chinese medicinal herbs, various roots and “pizzle,” a.k.a. beef penis. Just for me. Just in case. “Make you strong,” he promised mischievously. It was better than a box of chocolates.

As Chinatown has become one of L.A.’s trendiest dining destinations, its elderly immigrant residents live in a food desert, struggling to buy groceries easily and affordably.

Lupe was there for me again when I’d roll into Hop Woo like a fool after having over-imbibed, a fertile subject for blogging. He was determined to defuse my hangover before it got ahold of me. “Don’t worry, Eddie. I cook something good for you.” His cure was chicken feet and abalone soup spiked with his famous blend of Chinese herbs and roots. The relief was immediate.

After serving the magic elixir, he paraded out a platter of deep-fried duck tongues (beaks still attached) and a round of ice-cold Tsingtaos — I assumed this was the hair-of-the-dog portion of the hangover cure. He then drank with me as I regaled him with my adventures from the night.

If you’ve ever found yourself overwhelmed by Chinese restaurant menus, you know how helpful it is to have a menu printed in your first language, and for many in L.A., that’s Spanish. Hop Woo was the first restaurant in Chinatown to include Spanish on the menu.

Lupe himself was more fluent in Spanish than he was in Mandarin, his dialect being Cantonese. He modified certain spicy dishes by adding jalapeños. Hop Woo’s Thanksgiving Chinese turkey had origins in Mexican Thanksgiving celebrated in cities like Tijuana. Over the years, I’ve seen his dining room become more diverse as word spread that Hop Woo was the local Spanish-friendly Chinese restaurant.

A trilingual menu was only the beginning as far as separating Hop Woo from other restaurants in the city. Lupe offered crowd favorites from Peking duck to shrimp fried rice, but he made sure to keep his more adventurous clientele happy too. This was where his secret menu made its appearance.

We asked Times writers: Where do you like taking visitors to eat? From Redondo Beach to Atwater, Sherman Oaks to K-Town, here are some answers

Hop Woo’s off-menu fare was kept off the regular menu for good reason. The stuff can be pretty intense. Madeleine Brand’s show on public radio covered Hop Woo’s secret menu of deer meat and star melon, oysters with “hair vegetable,” deep-fried chicken knees, goose intestines, lamb testicles and armadillo soup. Vice Media shot an episode for its food channel about Hop Woo’s seven courses of boa constrictor, which included everything from the snake’s skin to the gallbladder bile. Nothing, and I mean nothing, was wasted.

Most of these dishes I wrote about in my food blog Deep End Dining because they weren’t meant for mainstream consumption.

Lupe could be counted on always. During the depths of the pandemic, when many residents of Chinatown were in despair, Lupe and his staff prepared hundreds of meals to give to those in need, even as his own business suffered. When it was time to help promote Chinatown, Lupe consistently said yes, while other restaurants bowed out. He had so much love for people. Above all, he loved feeding everyone, like a true chef.

Family was of ultimate importance to him — anybody’s family. He came from a big one: seven brothers, three sisters. They all helped one another. He deeply loved his wife and daughters. He’s so proud that Mary is, in a way, following in his footsteps with her baking business, Mary’s Makeshop.

He was also like any restaurant owner who faced the realities of the business day to day. His staff was important to him. They were truly family, some of them with him since Day 1. There were many employee celebrations throughout the years that brought joy and levity to the often long and grueling days, some days closing as late as 3 a.m. I’ve witnessed those times. The good times. The difficult times. The kind of times that make up life for each of us until there’s no time left at all.

Lupe Liang’s passing could be the end of a Chinatown institution. Lupe ran out of time much too soon. He had so much more to give to Chinatown. His Chinatown.

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.