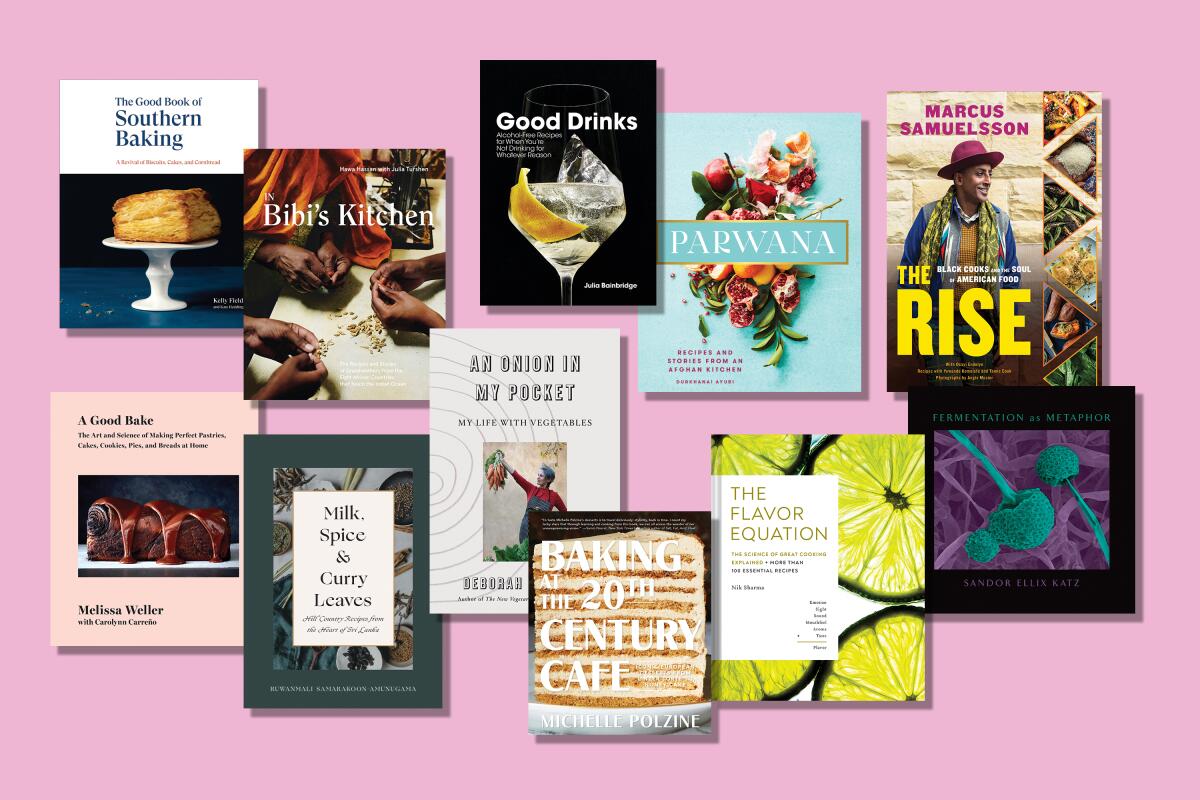

The 11 best new food books to add to your collection

- Share via

Cookbooks are always about connection — written to share the love of a cuisine or celebrate ancestry, or sometimes to eulogize broken bonds and safeguard history.

If you’ve run out of ideas or motivation for preparing your next meal, if you’re longing to be somewhere far away or want to explore fresh approaches to comfort food at home, or if you’re thinking about the broader context of food in our troubled culture, take heart and inspiration from 11 standout books of the season.

‘Baking at the 20th Century Cafe’

“Admit it,” begins the jacket copy of Michelle Polzine’s hefty, handsome book. “You’re here for the famous honey cake.” Well, yes and no. The 10-layer version of the Russian cake that Polzine serves at her cafe in San Francisco’s Hayes Valley, given mysterious depths by caramelizing the honey and lightened by dulce de leche in the frosting, deserves its legendary status. Honestly? I likely won’t bake this opus myself, nor roll out strudel dough thin enough to cover a table, as Polzine instructs; I will go eat them immediately on 20th Century Cafe’s marble counter the next time it’s safe to head north. But many other less involved and richly gratifying desserts (cranberry-ginger upside down cake, sherry trifle with Meyer lemon mousse, black walnut and buckwheat tea cakes) make the book worth owning. So does the indomitable life force of its author, whose mischievous spirit shines as brightly in her sentences as it does at her restaurant.

I can envision Nik Sharma — a molecular biologist turned pastry chef, columnist and author — lying awake at night, arranging and rearranging the elements of flavor in his mind the way Beth Harmon imagines moving chess pieces on the ceiling in “The Queen’s Gambit.” In his second cookbook, Sharma invites readers to consider recipes through the lens of science. Engaging charts on food pigments, aromas by chemical structure and the functions of taste buds lead to chapters grouped by aspects of flavor. Among them are “brightness” (spareribs in malt vinegar and mashed potatoes), “sweetness” (saffron swirl buns with dried fruit), “richness” (crab tikka masala dip) and “savoriness” (Goan shrimp, olive and tomato pulao). Dense in information and balanced by Sharma’s color-saturated photography, “The Flavor Equation” never loses sight of the most critical calculation: deliciousness.

When Sadelle’s, a re-imagining of a Jewish deli from New York’s Major Food Group, opened in 2015, the buzz hummed loudest over Melissa Weller’s pastries: the exceptionally delicate dough of her rugelach, the crackling layers of her salted caramel sticky buns, her plush take on chocolate babka. Behind the comforting sweets is a mind of science. Weller was a chemical engineer before switching careers, and she brings the discipline to breads and viennoiserie — and also to layer cakes and brownies. Which is to say: Don’t be daunted by the length and detail of the recipes. Weller, who authored the book with Carolynn Carreño, writes in a precise but familiar voice. When she suggests letting the dough for oatmeal cookies rest in the refrigerator for four days to achieve an ideal crisp-chewy texture, trust the process: They are exceptional.

‘The Good Book of Southern Baking’

Gently sweetened buttermilk cornbread. Angel biscuits (and drop biscuits and sweet potato biscuits!). Peach, blueberry and bourbon cobbler. Hummingbird cake brimming with pecans, pineapple, banana and warm spices. The world can use more top-notch Southern sweets right now. Kelly Fields — owner of Willa Jean, a bakery and restaurant in New Orleans loved as much by locals as visitors (which says a lot) — is one of this generation’s virtuoso pastry chefs. Her baked goods and desserts sing of the region without sliding into stereotypes; these recipes are honed but not daunting. Co-written with Kate Heddings, “The Good Book of Southern Baking” is the kind of cookbook you’ll grab from the shelf, thumb through and say, “I can do this.” Los Angeles photographer Oriana Koran stunningly captures New Orleans, Fields’ kitchen style and (especially with the picture of Fields’ hand smashing a strawberry cake on page 255) her wry humor.

Non-alcoholic drinks concocted by our savviest bartenders have made quantum leaps since they first began appearing on menus under the wince-inducing label of “mocktails.” Julia Bainbridge took a cross-country road trip in 2018, collecting recipes and tracing schools of thoughts around the subject (a big one: imitate classic cocktails or no?) into a compendium that considers every angle. Boozeless concoctions often lean syrupy. Bainbridge addresses this head-on: “The tension between sweet, sour, salty, bitter and umami is what the palate wants in a drink whether it contains alcohol or not.” Organized by their time-of-day appeal, with a helpful rating for the commitment level it takes to make them, recipes bounce from hoppy to citrusy, creamy to herbal, refreshing to intense. One favorite: U-Me & Everyone We Know by former Los Angeles bartender Gabriella Mlynarczyk. It’s an uplifting mix of tomato-watermelon-basil juice, simple syrup, lemon juice and a splash of umeboshi vinegar.

Hawa Hassan — a native of Somalia who modeled in New York before founding the bottled sauce company Basbaas — has assembled a project that is equal parts vital documentary, compelling scholarship and cookbook. With food writer Julia Turshen, she collects stories and recipes from bibis (grandmothers) who represent eight countries in East Africa that touch the Indian Ocean: Eritrea, Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique, South Africa and the islands of Madagascar and Comoros.

Dishes as varied as stewed plantains, denningvleis (lamb braised in tamarind), cornmeal porridges, spaghetti with spiced beef, chicken biryani and steak sandwiches doused with piri piri shed light on history, colonization, cultural connections and the daily lives of these women and their families. Try one of Hassan’s favorite comforts: digaag qumbe, a spiced chicken stew with potatoes and carrots in a yogurt and coconut sauce (served over rice or, as Hassan prefers, over a bed of spinach) with banana alongside as traditional accompaniment.

‘Milk, Spice and Curry Leaves’

Ruwanmali Samarakoon-Amunugama grew up in Canada; her parents immigrated to Toronto from Sri Lanka, and her mother prepared family recipes from the island’s lush, central hill country to keep her children connected to their heritage. As a teenager, Samarakoon-Amunugama began taking detailed notes on her mother’s cooking and on dishes she tasted during trips to Sri Lanka. After decades of observing a lack of Sri Lankan cookbooks on Canadian store shelves, she decided to help fill the void with her own collection of recipes.

Samarakoon-Amunugama sets the scene (“My late grandmother’s home in Peradeniya sits on a property that you wish only to walk barefoot upon”) and lays out the foundation of the cuisine: coconut is a bearing wall for flavors; onions, garlic, ginger, chiles, curry leaves and spice blends become frequent building blocks. She makes it clear where substitutions might be acceptable (frozen and even dried coconut can stand in for fresh) and where they are not (store-bought curry powder is no replacement for roasting and grinding your own). Her careful instructions and adaptations for North American cooks culminate rewardingly in the recipes such as peppered beef with coconut milk and black mustard seeds, its clinging sauce by turns rich and spicy and sharp.

I’ve been longing to visit Parwana Afghan Kitchen in Adelaide, Australia, since ex-L.A. Weekly restaurant critic Besha Rodell wrote about it for her Australian Fare column in the New York Times in March 2018. The restaurant’s cookbook — written by Durkhanai Ayubi, who runs the restaurant with her mother, Farida Ayubi, father, Zelmai Ayubi, and four sisters — conveys far more than escapist fantasies during a pandemic. Narratives between recipes and evocative photos detail centuries of Afghan customs and, more urgently, the modern political crises that led the Ayubi family to flee Afghanistan to Pakistan and ultimately to migrate to Australia. Farida Ayubi’s recipes for jeweled rice dishes, herbed kabobs, mantu (dumplings bathed in yogurt and tomato sauces) and gently spiced sweets exist as remembrances and acts of preservation. “Parwana [the word is Farsi for ‘butterfly’] is underpinned by my mother’s vision — her belief that through her knowledge of the art of Afghan food, gifted to her from her mother and her foremothers, she had been entrusted with a treasure of old, a symbol of Afghanistan’s monumental and culturally interwoven past.”

The most important cookbook published this year begins with a manifesto: “Black food is not monolithic. It’s complex, diverse and delicious — stemming from shared experiences as well as incredible individual creativity. Black food is American food, and it’s long past time that the artistry and ingenuity of Black cooks were properly recognized.” Megawatt chef Marcus Samuelsson teams with James Beard Award-winning writer Osayi Endolyn to frame the stories and cultural contributions of more than 50 Black chefs, journalists and activists .

Accompanying Endolyn’s perceptive, unflinching essays on many of the featured talents are recipes Samuelsson developed with Yewande Komolafe and Tamie Cook that honor the individuals. There’s a gumbo inspired by Leah Chase; a saucy, okra-embellished shrimp and grits as tribute to Ed Brumfield, the executive chef at Samuelsson’s Red Rooster Harlem; and spice-rubbed spare ribs with kimchi-style pickled greens as a nod to Los Angeles chef Nyesha Arrington.

“The Rise” is as useful in the kitchen as it is meaningful on your reading table. To spur further immersion, an invaluable resources section highlighting other chefs and media is provided at the back of the book: It’s a conclusion and also a beginning.

TWO NOTEWORTHY NON-COOKBOOKS:

Sandor Katz calls himself a “fermentation revivalist.” He’s spent the last 25 years learning and practicing the microbial transformation of foods into sourdough starters, yogurt, kombucha, kimchi, beer, wine, cheese and cured meats. His dedication meets a moment in America when the food world has embraced fermentation as an aspect of culinary reclamation — which is to say, as a reaction against industrialized food systems.

With this slim, 118-page volume, Katz turns from recipes to philosophy. He considers the wider meanings of fermentation: “Anything bubbly, anything in a state of excitement or agitation, can be said to be fermenting.” Later he is more specific: “When a group of people whose reality has been pathologized organize to claim respect for who they are, that is fermentation.”

“Fermentation as Metaphor” is a swift, spicy, timely read. Addressing viruses (including his own experiences living with HIV), our obsessions with cleanliness and borders, and the need for ferment in a time of social upheaval, Katz is provocative but also calm and reasoned. If his observations stoke your literal appetite, check out his bestselling books “Wild Fermentation” and “The Art of Fermentation.”

Since publishing “The Greens Cookbook” in 1987, Deborah Madison has been one of America’s guiding thinkers and instructors around modern plant-based cuisine. She cooked at Chez Panisse before becoming, in 1980, the founding chef at still-thriving Greens in San Francisco. Her books mirrored the evolving California culinary ethos: eat what grows close to home, study the world’s cuisines for unending inspiration. Any serious cook should own her two knowledge-packed masterworks, “Vegetarian Cooking for Everyone” and “Vegetable Literacy,” if only to crib her gifts for flavor combinations.

“An Onion In My Pocket,” Madison’s foray into memoir, traces her upbringing in Davis, Calif., the path to opening Greens, the hard lessons she learned helming the restaurant and her transition to cookbook author. The kernel of the narrative, though, emerges from the nearly 20 years Madison spent as a student and practitioner at the San Francisco Zen Center, beginning in the early 1970s. It’s a period of her life, she admits at the start of the book, that she’s spent little time examining until now. The self-inquiry pushes her writing into absorbing terrains.

Though I’m a long-lapsed Zen student, I recognize the existence Madison describes: the aching knees after hours of meditation, the disappearance into community, her struggles as tenzo (head cook) to please everyone’s tastes. Zen is anything but the spa-induced calm that popular culture makes it out to be. Practice teaches you to observe the mind — your own as well as the commonalities of the human mind — and there’s a wonderful, ambling quality to the book’s flow that feels keenly influenced by Madison’s reclamation of her Zen years.

A passage on page 127 discusses how the food served during a practice period near the end of her time in the Zen community had morphed from monkish (often simple soups and grains) to on-trend; she was startled to find one bowl during lunch filled with an arugula and goat cheese salad. “It made everything the same,” she writes, “and what had been special about eating in the zendo [meditation hall] was the opportunity to experience food that was truly modest, even humble, and maybe not very well prepared, and have it be okay. Even more than okay. For me zendo food was about having less and discovering that it was more.”

The intersections of food and spirituality are under-explored topics in American literature. Nourishment can be about more than an inventive recipe or a dazzling meal. Madison’s reflections remind us of larger, slipperier kinds of hunger that call to be satisfied.

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.