Who knew Vespertine’s Jordan Kahn could make such comforting takeout food? (He did)

- Share via

Before Jordan Kahn’s unearthly project Vespertine took up residence in the four-story building at 3599 Hayden Ave. in Culver City, architect Eric Owen Moss simply called his structure “Waffle.” No nickname could be more apt: Its form resembles several squared-off Eggos dipped in hot chicken spices and built into a wobbly fort. From a certain angle its heaving walls also suggest a squat beast that has recently gobbled breakfast. Even now, empty of guests, the restaurant somehow looks full.

I study the tower and its outlandish beauty in my rearview mirror, one of a half-dozen cars waiting in the parking lot for the staff to bring out our takeout dinners. The late April sky seems more deeply blue against the building’s mutable red. Soon we will rush home to unpack our meals. We don’t know the specific contents yet, only that the week’s theme is “A Southern Supper.”

While idling I think about my last time inside Vespertine — which, when fully operational, is one of the most polarizing indulgences on the planet. The dinner was in September, with three other food writers. Nothing that Kahn prepares for his tasting menu, which can last more than four hours, appears familiar. No cultural touchstones, no bragging about ingredient provenance: The near-sentient building is the defining sense of place. He channels the alien in his cooking; he dwells in the future, not the past.

Still, having been to the restaurant previously, I recognized ever-evolving variations on some of Kahn’s visual wonders: a cookie of burnt onion, blackcurrant and flowers in a vessel shaped like an obelisk with its point chopped off; a dish whose edible surface was as black and craggy as asphalt, hiding Hokkaido scallops. Preserved bougainvillea petals glowed in their translucence. Discs of almond buttercream (concealing icicle radishes and trout roe) revolved inside the bowl like planets circling in their own lonely orbits.

Hypnotic, cyclic music from the Texas band This Will Destroy You at turns lulled me into a trance and put me on edge. Servers, quietly ascending and descending internal staircases, were polite but austere and sometimes a little spooky — a tone Kahn has set since the restaurant opened in 2017.

A meal at Vespertine can quickly add up to $1,000 for two people. Writers have rhapsodized, ranted and scratched their heads, sometimes in the span of one article. I ate there with a well-traveled friend last year and she practically ran screaming from the place. Chefs tend to love it. Alex Stupak, who owns New York’s Empellón and worked with Kahn at Alinea in Chicago, told Grub Street last year, “I can’t think of a more original, perfectly curated and artistically subtextualized experience than Vespertine in the last decade.”

I respect Kahn and the purity of his aims, but in the building I’ve never quite relaxed into enjoyment.

***

Today, in the center of a devastating pandemic, Vespertine’s website still describes its ambitions as “a gastronomical experience seeking to disrupt the course of the modern restaurant.” The novel coronavirus has accomplished this goal more swiftly and terribly than any of us could have imagined.

Kahn, like many chefs, sprang into survival mode after the shutdown, embracing takeout menus to keep his staff employed. He started with straight-ahead comfort dishes (chicken thighs overlaid with a dense, bright salsa; a gorgeous black carrot salad with endive; brownies) that slightly intersects with the menu of his nearby daytime restaurant, Destroyer. On the second menu, he packaged pork belly banh mi, a savory rice porridge with an egg yolk and hazelnuts, and other menu signatures from his years as chef of now-closed Red Medicine in Beverly Hills. Kahn’s cooking, by necessity, had an identifiable time and place again. It all felt nourishing, and it tasted plainly delicious.

When he announced the “Southern Supper,” I learned Kahn grew up in Savannah, Ga. I’m a native Southerner; I lived in Atlanta for nearly 20 years. I felt especially pulled to the theme of this menu. Could a chef who felt called to forge a cuisine with no cultural anchors circle back to soulfully reconnect with the foods of his childhood?

In the Vespertine parking lot I recognize Megan Sokol, the restaurant’s front-of-house manager. Instead of delivering dishes in stone bowls with mysterious one-word descriptions, she wields a clipboard to check off takeout orders. I have the impulse to leap from my car and hug her. Of course I don’t.

On the roof of the building where my colleague Andrea Chang lives, we unpack the meal. It’s a splurge at nearly $50 per person, but there’s so much food. We’ll have leftovers.

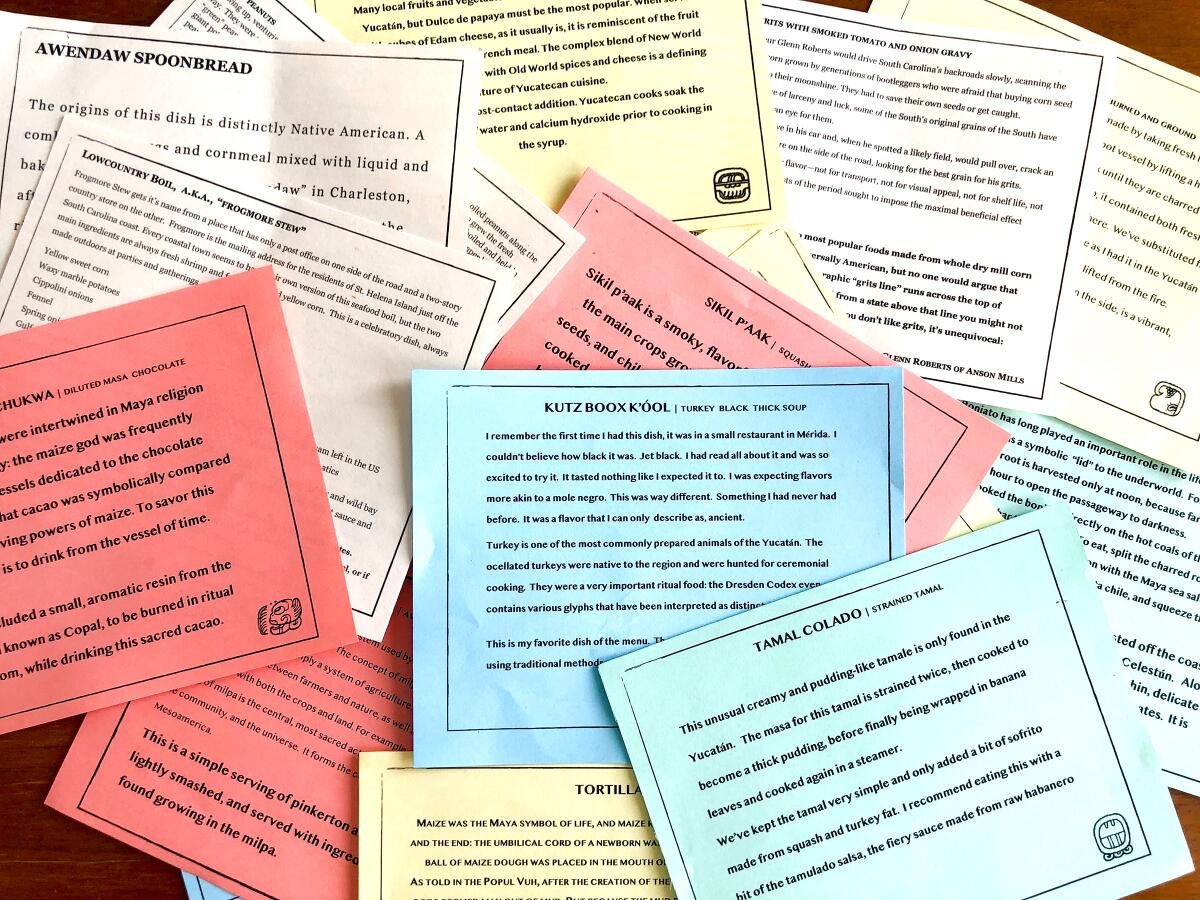

I hold up a sealed plastic bag full of shrimp, potatoes and hunks of sausage and corn on the cob. “Is this Frogmore stew?” I ask aloud through a fog of memory. Andrea looks at me questioningly. We flip through the menu’s detailed explainer cards (a 180-degree departure from Vespertine’s usual enigmatic aesthetic). Sure enough, Kahn knows the dish — also called Lowcountry boil, the ingredients simmered in beer and spices and shrimp stock — by its micro-regional name of Frogmore stew as well.

There are creamy white grits from Charleston’s Anson Mills, with a side of smoked tomato gravy, and collards cooked to utter tenderness in a balance of pork, vinegar and brown sugar. Cornbread is nearby to sop up the pot liquor from the greens. For snacks Kahn has made boiled peanuts, a staple roadside snack in rural Georgia; bread and butter pickles; and pimento cheese with crackers made from benne, the West African seed brought to America on slave ships. Sweet potatoes have been doused in blackstrap molasses and sorghum; bitterness equalizes the sweetness. A box of raw vegetables comes with a buttermilk dip; buttermilk reappears in a small round custardy pie painted with berry sauce.

I reach for the small bottle of hot sauce instinctively, before cognitively recognizing that Kahn would think to include hot sauce for this supper.

Art exists in the cooking, a different face of Kahn’s virtuosity. My reaction is largely personal. This feast, the cumulation of its scents and flavors, takes me home. I’d wondered what home even meant during a pandemic. Now I feel it. The doors inside I’d barred to protect myself — the ways we’ve all needed to shelter to survive — open for a minute. Warm California winds blow across the rooftop and pass through them. I clench my jaw to keep from crying in front of a co-worker. Tears brim over anyway.

***

Practicality largely overrules surges of emotion in this moment. Where is the place for artful creativity during a worldwide crisis? People are suffering and dying. Tens of millions have lost their jobs; some of L.A.’s best restaurants already have closed permanently. There’s little bandwidth for “difficult” books or films or challenging, abstruse food. Difficulty is oppressive and unpleasant; you can be difficult only in times when you can waste a meal. How out the window the idea seems, in times of imperiled survival, to engage in any sort of high-mindedness about art and beauty and pleasure.

Talent alone isn’t enough to endure this disaster. Yet most chefs choose their professions for a reason: Among the bills and the long hours and the repetitiveness and the politics of the kitchen there is an unshakable urgency to create. An outlet to express has to be found, spiritually and financially, even when dining rooms must remain unoccupied. Creativity is survival.

Sushi legend Mori Onodera is busy crafting pottery. After shutting down his businesses temporarily to cook for hospital workers, chef Josef Centeno has built takeout windows into his downtown restaurants Bar Amá and Orsa & Winston; he’s also ramping up a clothing line called Prospect Pine, for which he hand-dyes the garments. Guerrilla Taco’s Wes Avila is considering teaching a Zoom class on every aspect of starting a food truck. Compelling pickup/delivery startups such as FEW For All, Ceci’s Oven and Parm Boyz are materializing weekly.

The fruits of creativity can strengthen a sense of social cohesion in a time of isolation. Even sitting among a row of cars with popped trunks in front of Vespertine feels like community, knowing we’ll soon be eating the same inventive meal in our own homes.

Kahn has modified his culinary output more radically than any other chef in the city — arguably the country. Following the coastal South, his current menu pays tribute to the foods of the Yucatán Peninsula. Its centerpiece is recado negro — a turkey stew with an inky sauce that takes three days to prepare and involves cooking chiles until they catch on fire. It resembles mole but the flavor veers in smokier, duskier directions.

Among cochinita pibil, a creamy tamal, candied papaya with fresh cheese, tortillas and barely sweetened hot chocolate (this is another generous meal with illuminating liner notes), signs of Kahn’s bleeding-edge artistry are reasserting themselves. A riff on ceviche is crowned with passiflora caerulea, or wild passionflower, a favored drink garnish at Vespertine; the blue and white bloom, which Kahn harvests from Malibu’s canyons, is so spellbinding you want to stare into its mazelike center, searching for meaning. A menu card describes a Mesoamerican method of using a hot rock lifted from an earthen oven to char and cook beans. In the carryout bowl, Kahn meticulously arranges the beans around a stone. (“Please do not eat the rock,” the card says.)

Where had Kahn leapt with this menu? To a cuisine about which he was curious? Was there another personal correlation? I’d always taken Vespertine at face value; its self-contained context seemed the whole point. These new menus prompted questions.

***

“I’m a bit of a mutt,” Kahn says over the phone a few days later. “I’m half-Cuban, a quarter Sicilian, a quarter Hungarian; my father was adopted by Ashkenazi Jews from New York. With a background of classic French training and modern progressive cuisine [French Laundry and Alinea, among others] and a restaurant in California, I’m not sure what cuisine I’m supposed to be making. It can be very hard to distinguish between the person and the chef. There are times when the two are connected, and also often they’re very much at odds with each other.”

During a 70-minute conversation, we talk about how his attraction to Moss’ building was like a gravitational pull and how the meals he serves there stem from the surroundings almost intuitively. But even Kahn, one of the most radical innovators, has roots — and he draws on them more than you might think. He learned to cook from his Cuban grandmother, who fled the island with Kahn’s grandfather and mother, landing in Spain before moving to the United States. She would ask Kahn, about 8 at the time, to taste as dishes came together, quizzing him in Spanish about whether the salt and acid in the ropa vieja was on point.

He connects parallels: “She cooks from what’s inside of her. And when I cook from what’s inside of me, it doesn’t look like what you think it should look like. I can only follow my own voice.”

He’s still mulling whether to create a Cuban menu during the shutdown. “It’s tricky,” he says, “because it’s really a sacred cuisine to me.” We’re more likely to see handmade to-go containers from compostable ingredients, a problem he’s fixated on solving.

The culinary journey to the Yucatán sprang from his Cuban heritage; part of his family there came originally from Quintana Roo, and he traveled to the Yucatán with kin when sanctions on Cuba lifted last decade. This part of the world has been percolating in him for years now. Destroyer is named for the asteroid or comet that created the Chicxulub crater, now buried underneath the peninsula. “I thought it might be a nice nod to do some cooking for my ancestors,” he says.

Have these culinary side trips to the South and Mexico been fulfilling? Kahn tells me he’s received plenty of wonderful feedback. “When guests email to say it’s felt like a surprise — made them think or it made them giggle — or made for a momentary escape, I’ve been like, OK, we’re on the right path, because a place like Vespertine is meant to be escapist. We don’t talk about culture or locavorism because, even though that’s all in there, the experience is not about anything other than your journey.”

With the popularity of his takeout efforts, which have all eventually sold out, Kahn hasn’t furloughed a single employee; he’s kept them all at their previous pay rates. It’s clear through our whole talk, though, that however he may be funneling his personal sensibilities into these menus, he really wants to get back to his calling — to serving meals inside the building. He’s happy I’ve been uplifted by his recent cooking but he would much rather I’d called to discuss an indecipherable Vespertine dish I was still puzzling over.

I ask him about the place of artists in a fractured world. He bristles at the pretentious overtones of the A-word but considers the question. “What I think about a lot with what we do here ... it’s not about ‘restaurants.’ It’s not about food. It’s not about chefs, not about farmers or foraging or plates or techniques or any of this. It’s about the connection. An artist can take something and articulate an emotion that strikes you so perfectly right when you need it.”

Yes. With Frogmore stew brought home in a paper bag — and maybe soon with edible gravel and moons of Saturn made from buttercream, consumed inside a magic tower.

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.