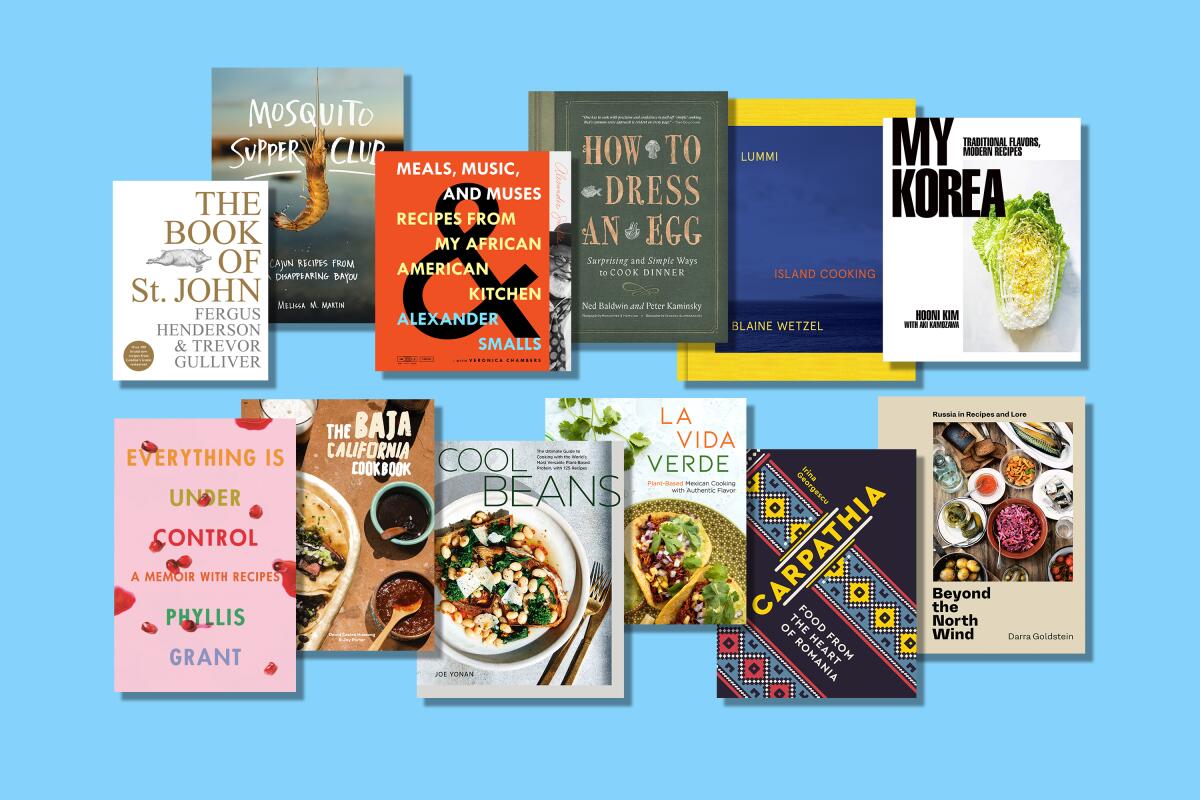

12 cookbooks that refresh the spirit and inspire in the kitchen

- Share via

This is an excellent time to have some absorbing cookbooks on hand. Not only because many of us could use inspiration figuring out what to cook while we shelter but also because we’re craving connection.

A parallel has emerged between restaurants and cookbooks in recent years: In the same way that chefs are expressing autobiography through their menus, hazarding to reveal themselves and where they come from, the best cookbook authors have also become willing to risk exposing their truest selves on the page.

It’s a daunting feat, being equal at recipe mastery and storytelling. Some of the recent books that achieve this remind us about what we’re missing while restaurant dining rooms remain closed; others shed light on home traditions around the country and the world. Each offers us a chance to disappear into finely wrought words and worlds and, if we’re up to it, into our kitchens.

The Baja California Cookbook: Exploring the Good Life in Mexico

What could have been a day trip two months ago now feels like a distant reality: driving 200 miles south to Baja California’s Valle de Guadalupe and lingering over duck sopes at Fauna, the fine dining restaurant where David Castro Hussong is chef. This culinary homage to his birthplace, written with Jay Porter and sumptuously captured by Los Angeles photographer Oriana Koren, is the closest we’ll get in the immediate future. Hussong cooked at such luminary kitchens as Blue Hill at Stone Barns and Eleven Madison Park, but the recipes in the book are largely approachable. Grilled halibut burritos, charred cabbage over spicy cabbage purée (a Fauna essential), and mussels and pork simmered with guajillo chiles and garlic outnumber (worthy) projects like beer-battered fish tacos fried in lard and dressed with three sauces. The introduction, in which Hussong sets a scene of the area’s markets laced with local history — it turns out, for example, Russian emigrants in the 1920s began planting the vines for what has become a thriving wine region — makes the longing to join him in the Valle all the more powerful.

Beyond the North Wind: Russia in Recipes and Lore

Darra Goldstein — the Russian scholar who founded the academic food magazine Gastronomica — first traveled to the U.S.S.R. in 1972. Grocery shelves were bare, but new friends showed her where to find street snacks like meat pies and hot doughnuts. It lit a culinary curiosity in her that never extinguished. In 1983 Goldstein published her first book on Russian cuisine, a mix of Soviet-era curios and French-inspired haute cuisine. With “Beyond the North Wind,” she challenges herself to keep foraging past layers of stereotypes and borrowed cultures to the flavors and techniques that are most fundamentally Russian. Savory pies, dumplings with nuanced fillings, 20-minute pickles and fermented fruits and vegetables: The food has (to me) surprising kinship with contemporary American cooking. It’s one way the book, while acknowledging political fractions, also illuminates commonalities. The stories of her Russian travels and her many fascinating asides on hospitality traditions makes it a riveting read, no cooking required. Anyone looking to change up the morning routine, though, should try Goldstein’s recipe for lightly fermented oatmeal.

The Book of St. John

It was the makings of full-circle glory. St. John, the legendary London restaurant run by chef Fergus Henderson and business partner Trevor Gulliver, had helped persuade American chefs — and by extension the dining public — to embrace whole animal cookery and uncomplicated, seasonal pairings of meats and vegetables. The duo were on course to open their first restaurant in America this year, in Culver City. If the project’s future is uncertain, we at least have their cookbook, released late last year to commemorate the flagship’s 25th anniversary. The expected St. John signatures — bone marrow with parsley salad, a set of instructions labeled “A Happy Journey Around a Pig” — dutifully appear, but the variety of pickles and homey dishes (braised lamb with frozen peas, Welsh rarebit) is a reminder of the restaurant’s range. I was particularly happy to see the custardy, sherry-laced trifle I’ve loved as a finale to dinners at St. John. One note: Measurements are given in grams and liters, which might require converting for American cooks.

Carpathia: Food From the Heart of Romania

“Romania is a culinary melting pot,” begins Irina Georgescu. “Its character is rooted in many cultures — from Greek, Turkish and Slavic in the south and east, to Austrian, Hungarian and Saxon in the north and west.” Outlining the influences of the chef’s native cuisine gives the reader anchoring context, but Georgescu beautifully details how Romanian cooking has melded into something soulful and self-possessed. Hearty succor fills the pages: baked apples stuffed with ham and feta; pan-fried chicken with caramelized quince; grape leaves filled with sticky rice and raisins; a cake, called chec, marbled with fresh berry syrup. A warm wryness seeps into Georgescu’s writing. She translates bors, a ubiquitous wheat-based fermented liquid for flavoring broths, as “The Ingredient.” And she has this to say about scovergi: “When I was growing up, these cheesy, gooey flatbreads were something to munch on while chatting around the table, or watching television in the living room, even when television was only on for two hours a day and full of programs about the achievements of the Communist party.” A captivating immersion course.

Cool Beans

Long before the bean reached its current pandemic-driven scarcity, Washington Post food editor Joe Yonan was a dedicated vegetarian and legume proselytizer. His bible aims to convert. He lays out persuasive arguments about beans’ versatility, healthfulness and deliciousness, particularly when the heirloom varieties come from Napa Valley’s cult bean seller Rancho Gordo. Then he gathers recipes from every corner of the globe: Ecuadorian lupini bean ceviche, Nigerian black-eyed peas and plantains, Lebanese-style foul moudammas, Edna Lewis’ Southern baked beans (minus her addition of salt pork). Now Serving L.A. recently presented an online conversation with Yonan; host Evan Kleiman asked him to name his favorite recipe in the book. He hemmed and hawed and then called out the cacahuate (a.k.a cranberry or borlotti) beans flavored with garlic, tomatoes and chiles and crowned with pico de gallo — a recipe from chef “Lalo” Garcia of Maximo Bistrot in Mexico City. Its ease and lushness will make you a believer.

Everything Is Under Control: A Memoir With Recipes

Phyllis Grant opens her memoir (I’m sneaking one outstanding non-cookbook into the pile) by describing the tart dough she’s making in her Berkeley home kitchen, her two children nearby. The page’s single-line spacing suggests a poem. She juxtaposes the scene with flashbacks to cooking in white-tablecloth New York restaurants: “There is no Chef. / I lean all my weight into the flattened disc. / No dupes. / Roll, spin, quick flip, flour, exhale.” She details how her parents and grandparents met before settling into her own narrative; it lifts off as she becomes a dance student at Juilliard and flows into her grueling stint as a chef (the restaurants go unnamed, though her bio mentions that she worked at ’90s high-flyers Nobu and Bouley), her marriage to actor Matt Ross and the complexities of motherhood.

Every page has a unique layout. Some contain two lines; others one or two paragraphs. Without feeling contrived, the structure frames the writing somewhere between poetry and prose. It serves Grant’s candid, spare and rhythmic style. Food may be the throughline that connects her stories, but it is her searing honesty — around misogynistic kitchen culture, postpartum depression and grief in many guises — that propels the reader beyond evocations of chocolate souffles and avocado bowls. That said, dishes that loom large in Grant’s life reappear as recipes at the end. Big yes to jammy tomato anchovy sauce.

How to Dress an Egg: Surprising and Simple Ways to Cook Dinner

Ned Baldwin, chef and owner of Houseman in New York’s Greenwich Village, unwittingly wrote a book made for the moment: He and co-author Peter Kaminsky present 20 staple dishes, each with three to six smart variations. A recipe for “gently cooked shrimp,” for example, spins off into shrimp salad with peas, dill and tarragon; spicy shrimp with peanuts, mint and cilantro; buttery potted shrimp (an English pub standby); or shrimp rolls. Scanning riffs on pot roast, broccoli, roast chicken, grilled asparagus and, yes, dressed eggs sparks the brain to improvise with what’s on hand. A recipe for broccoli with poached prunes and speck is likely an homage to Gabrielle Hamilton’s East Village institution Prune, where Baldwin was chef de cuisine. He absorbed Hamilton’s aesthetic for the direct, common-sense pleasures of the table, and he makes them his own.

Lummi: Island Cooking

In August 2016, I had the most extravagant breakfast of my life at Willows Inn, a tiny luxury hotel and restaurant on Lummi Island two hours north of Seattle. It wasn’t caviar and truffles that made the meal opulent. It was the summer fruit — local wild strawberries, black huckleberries, white raspberries, plums and doughnut peaches so amplified in flavor it was like I’d never before known the true meaning of ripeness. Breakfast came the morning after a four-hour tasting menu orchestrated by Blaine Wetzel, the chef who turned Lummi into a singular destination. His cookbook — really more of an art book, with gorgeous, color-soaked photography by Charity Burggraaf — would have read like fantasy even before the crisis. The recipes really speak to other chefs; rice koji is a recurring ingredient, and few of us will ever lay our hands on bay leaf buds. But if you’re looking to drift to another galaxy, if you want to dream over green strawberries steamed with rhubarb and gooseberries, or gaze on the impossible, swirling beauty conjured from a dish humbly dubbed “heirloom peas and bitter greens,” Wetzel offers heady escapism.

Mosquito Supper Club: Cajun Recipes From a Disappearing Bayou

In 2006 New Orleans chef Melissa M. Martin fled post-Hurricane Katrina Louisiana for Napa, following a winemaker friend. While there she read “Cooking by Hand” by Paul Bertolli; his loving words about Italian cooking sparked epiphanies of her culinary upbringing in south Louisiana’s Terrebonne Parish. Her book is a love letter to Cajun culture in which she lays out plainly the history of the Acadian diaspora, her feelings on inaccurate portrayals of Cajuns and their foodways (no one is shouting “bam!” or blackening redfish) and the effects of climate change as her homeland slowly disappears into rising waters. The heart of the book gives way to utter beauty. Denny Culbert’s sweeping photos of bayous and fertile farmland will make you ache to travel. The book is named for the NOLA restaurant where she serves seasonal family-style menus, and though recipes like crab jambalaya and crawfish étouffée thrum with their specific sense of place, her smothered chicken and seasonal treats like blackberry dumplings translate so well they could be Californian.

Meals, Music, and Muses: Recipes From my African American Kitchen

Intertwining the subjects of food and music comes innately to South Carolina native Alexander Smalls, who was a professional opera singer before refocusing his career as a chef and restaurateur in New York (including, most recently, the Cecil at Minton’s Playhouse in Harlem). He also puts the pairing into a larger context: “In the United States, food and music are inextricably linked, especially in the African American culture. Both Southern music and Southern food are rooted in a knotty lineage that connects West Africa and Western Europe.” He matches dishes to musical forms — appetizers with jazz, starchy comforts with spirituals — but what’s most compelling are the essays that pepper the book, a mix of memoir, scholarship and conversational reassurance. These are Smalls’ takes on classics, the dishes forged by the hands and minds of black cooks that are the backbone of American cooking. Fried okra, creamed corn, succotash with fresh mint, peach shortcakes: His recipes have me missing the South and yearning for summertime.

My Korea: Traditional Flavors, Modern Recipes

Early in his enveloping guide to Korean home cooking, chef Hooni Kim — who owns two Manhattan restaurants, Hanjan and Michelin-starred Danji — details rousing eating experiences during early visits to Korea and then relocating from the U.K. to New York as a child and experiencing its Korean food culture. “Having spent so much of my youth in Koreatown,” he writes, “I understand the feeling of being transported by where you are and what you eat to a different time and place — despite the fact that the food there lacked any real flavor.” How might his life have been different had his family instead moved to Los Angeles, with its vast and superior Ktown? No matter: Kim’s book is a boon to anyone who savors Korean flavors. While Angelenos are missing Soban’s sanjang gejang (soy-marinated raw blue crab) and slurping doenjang jjigae in Jun Won’s dining room, we can study the dishes’ mechanics through Kim’s detailed instructions — and try our hand making straightforward jajangmyeon at home.

La Vida Verde: Plant-Based Mexican Cooking With Authentic Flavor

Five years ago native Angeleno Jocelyn Ramirez left a teaching career at Woodbury University to start Todo Verde, a catering company that serves plant-based dishes grounded in the Mexican and Ecuadorian flavors of her heritage. “La Vida Verde” details the building blocks of her repertoire — the ways she uses ingredients like jackfruit and tempeh for satisfying textures in tacos, tamales and pipiáns, and her approachable recipes for creams and cheeses made from nuts. Most persuasively, Ramirez makes the case that the fundamental deliciousness of Mexican cooking never relied on meat. “The things we love to eat are all flavored with plants (herbs and spices), and anything can taste great if you apply the same techniques to a plant-based option,” she writes. The notion applies to something as simple as guacamole given crunch with a mix of seeds or to an absorbing undertaking like mushroom-filled enmoladas blanketed in spicy sweet mole colorado. These are the flavors of Los Angeles we need right now.

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.