Finger lime: the caviar of citrus

- Share via

This year, for the first time, you don’t have to be a scientist or an Australian to taste citrus caviar from legendary finger limes, as the initial, very small harvest from commercial plantings in California has started to show up at local markets and restaurants.

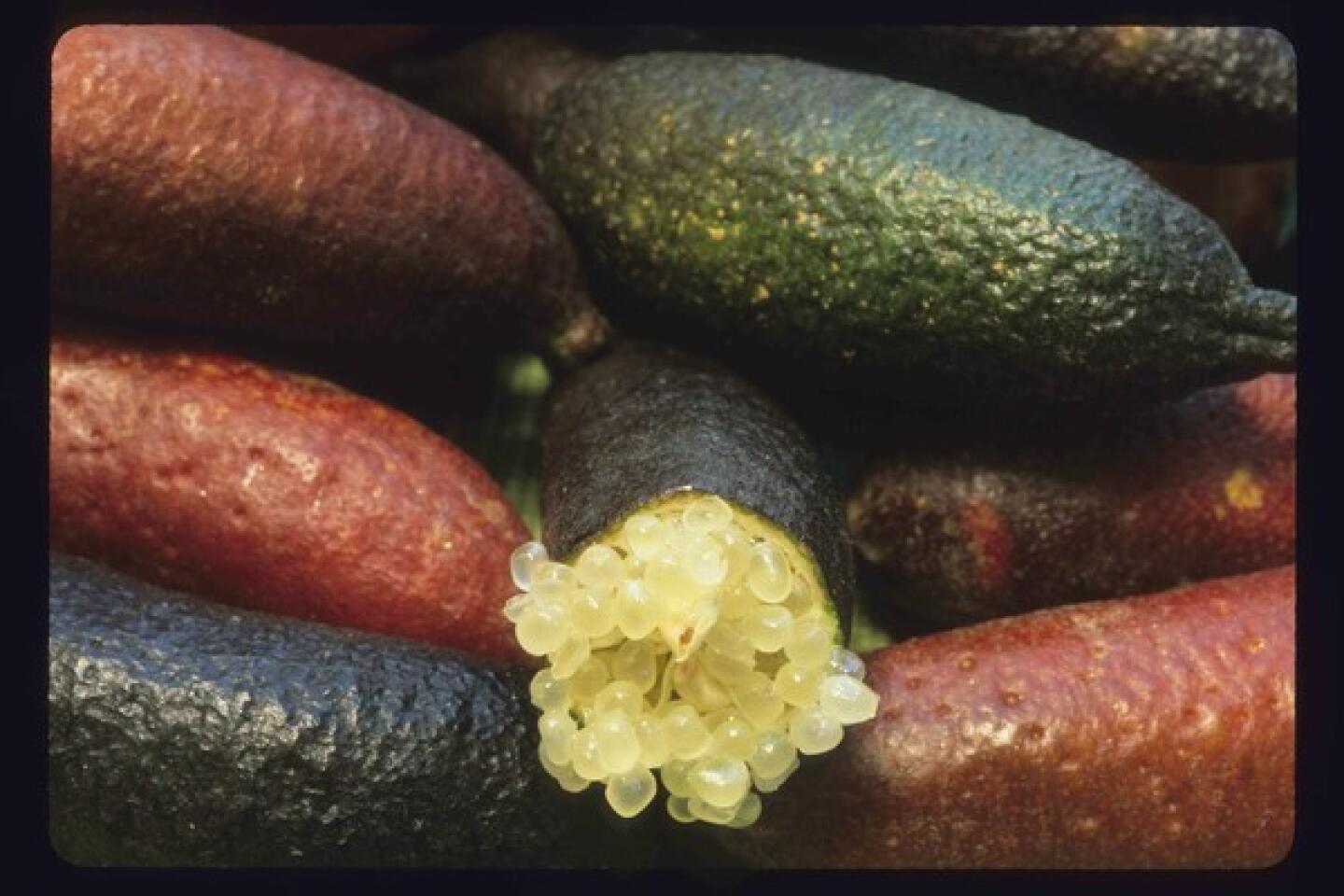

The finger lime is very different from other citrus, somewhat resembling a gherkin, elongated in shape, and up to 3 inches in length. Its skin is thin and can range from purplish or greenish black, the most typical color, to light green or rusty red. When the fruit is cut in half, the juice vesicles, which are under pressure, ooze out as if erupting from a mini-volcano. Unlike the tender, tear-drop-shaped juice sacs in standard citrus, the translucent, greenish-white or pinkish vesicles in finger limes are round and firm, and pop on the tongue like caviar, releasing a flavor that combines lemon and lime with green and herbaceous notes. The rind oil is also quite aromatic, and contains isomenthone, which is common in mint but rare in citrus.

What do you do with these digit-shaped prodigies? Like other acid citrus, they’re really too tart to eat fresh, but even so, the first time you encounter one, try cutting it in half and sucking out the caviar, squeezing it out of the rind like toothpaste from the tube, just to experience the fruit to the fullest. Next try some on a slice of Fuyu persimmon, to balance that fruit’s unidimensional sweetness with a pleasing smack of sourness. A little goes nicely with fish, but not too much, because the assertive flavor can easily overpower delicate seafood.

And mixologists are already developing trendy finger lime cocktails -- Australian margaritas, anyone?

Craft restaurant in Century City applies a vinaigrette containing what it calls “lime caviar” to both hamachi sashimi and Kumamoto oysters. “When the juice vesicles pop in your mouth, there’s an explosion of flavor,” says chef Anthony Zappola. “Customers are surprised, they think it’s some kind of molecular gastronomy, and they’re shocked to find that it’s from a natural piece of fruit.”

The fruits are not cheap, at almost $2 apiece, but a little goes a long way, he added.

Chefs, or more particularly the buyers who supply them, are vying furiously to obtain a supply. Kerry Clasby, the forager who provides finger limes to Craft, says she was sworn by the farmers who sell to her not to divulge their identities, lest they be besieged by finger lime fanatics. “Hopefully in a year or two the supply will increase and it’s not going to be an issue,” she says.

The finger lime is Microcitrus australasica, one of six species of citrus native to Australia, in this case to the eastern coastal rain forests. It differs significantly from conventional citrus in several ways, including having very small leaves and flowers, which in 1915 prompted the great citrus scientist Walter T. Swingle to assign the finger lime and its kin to a separate genus, Microcitrus. In 1998 the botanist and taxonomist David J. Mabberley proposed reclassifying Microcitrus as Citrus, but genetic analyses are inconclusive, and scientists have not universally accepted this move. A few decades ago scientists surmised that a Microcitrus species might be one of the parents of regular limes, but current evidence does not support this.

In the last two decades, as part of a wider interest in native “bush tucker,” Australian growers have cultivated finger limes on a modest scale, and fruit breeders have made selections and crosses to come up with improved varieties, in a rainbow of colors -- green, red, pink and yellow. Fresh finger limes cannot be imported legally to the United States, however.

The Department of Agriculture imported finger lime seeds or cuttings more than a century ago, and Swingle worked on the trees in a greenhouse in Washington D.C., but it seems that the species never became established in this country. The finger lime variety being grown today in California is derived from material imported from Australia, via Arizona, in the 1960s, when scientists planted it at the UC Riverside Citrus Variety Collection. For several decades scientists mainly used the trees for rootstock trials and hybridization, but they and visitors also got a kick out of the fruits, and five years ago the university released budwood of the variety for California nurseries to use in propagating trees. (Disclosure: I occasionally assist the collection as a volunteer researcher and photographer.)

From the introduction of a variety to the appearance of fruit at markets is a lengthy process, as nurseries figure out how to grow the trees, farmers buy and plant them, and the trees slowly mature and bear fruit. Currently one or two dozen farms around the state grow finger limes, on a total of about 10 to 15 acres. One of the oldest and largest groves is at Venice Hill Ranch, in Visalia, where three years ago the owner, James Shanley, planted 600 trees, which are just starting to bear in semi-commercial quantities this year. Peak season is November and December, but the trees produce some fruit year-round in coastal districts.

Growers have quickly discovered how difficult it is to cultivate this crop. The young trees of other citrus species typically produce extra-large fruits, but most juvenile finger limes are tiny, often no longer than an inch. When the fruits do reach a decent size, they tend to fall on the ground at the slightest breeze. The fruits mostly grow inside dense, bushy foliage, which bristles with nasty thorns.

“We’re really striking out in new territory with this baby,” says Lance Walheim of California Citrus Specialties, a grower and packer that will market the harvest from Venice Hill Ranch next week. “We’re still trying to figure out how to grow it.”

Barbara Foskett, a partner of CCS, says the fruits will probably be packed in small plastic clamshells, such as are used for berries, but that she has not yet set a price. Some of the harvest will go to Davalan Sales, a produce distributor in Los Angeles, and Robert Morse, a salesman for this firm, says that if there are enough finger limes to sell to retailers, they will probably go to high-end markets like Pavilions, Bristol Farms, Gelsons or Whole Foods.

Melissa’s World Variety Produce will also be receiving a consignment, and based on availability, may sell some directly to the public by mail order.

Just a few farmers market growers have planted finger limes, including Mud Creek Ranch of Santa Paula, which will sell a few fruits from its 12 trees at the Hollywood market this Sunday. Churchill Orchard of Ojai, which has 15 trees, will sell any remaining fruits when they start coming to the Ojai farmers market around Jan. 10.

Finger lime trees are available from several sources, including Maddock Nursery in Fallbrook ([760] 728-7172) and Four Winds Nursery in Winters.

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.