- Share via

Is there a best practices model for climate literacy education in Los Angeles, a program that integrates lessons across all subjects for students of all ages in an environment prioritizing outdoor learning?

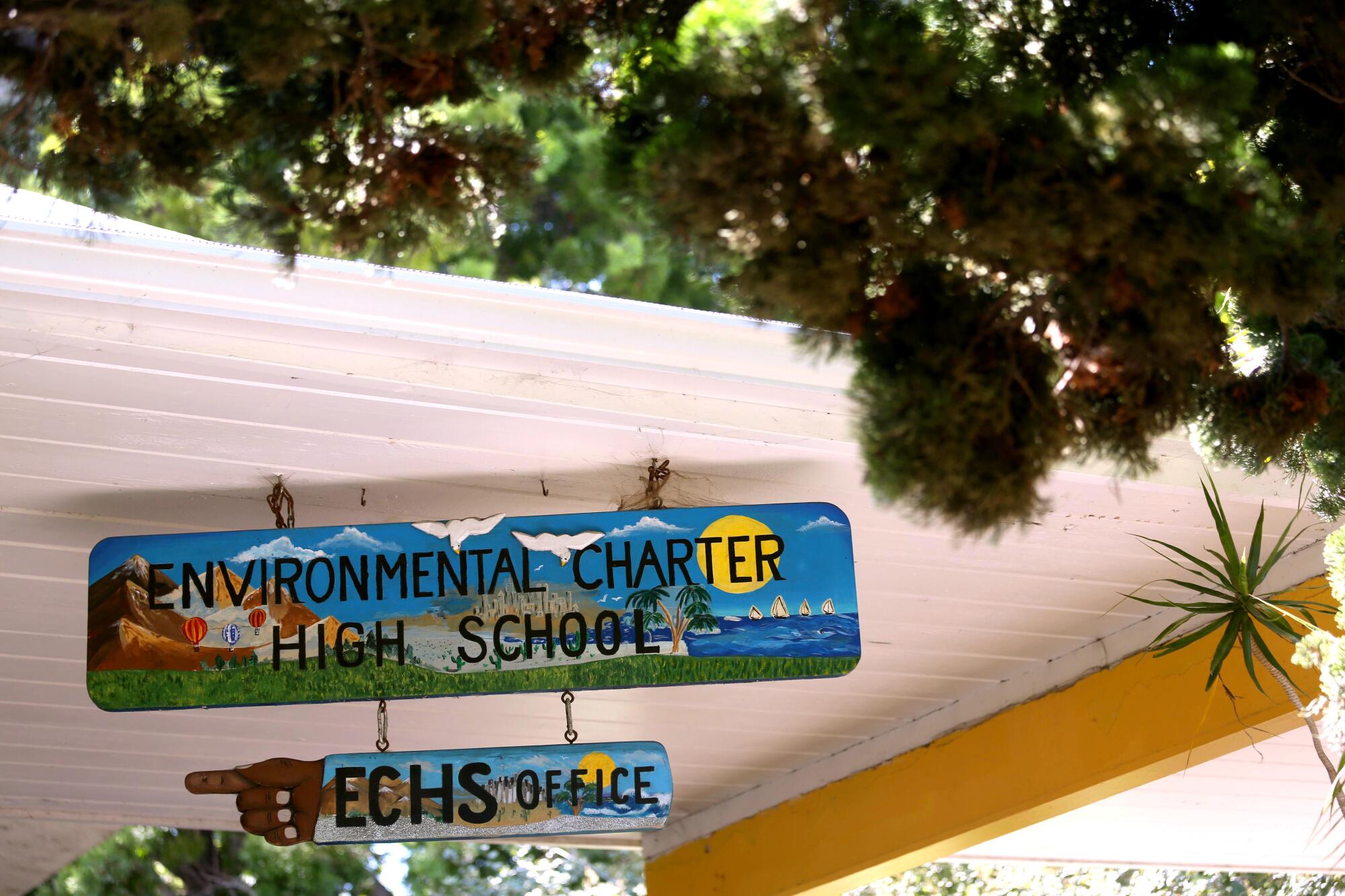

Twenty years ago, when she founded Environmental Charter High School’s Lawndale campus, Alison Diaz believed the answer was no.

A former public school teacher, Diaz said she believed that students from poor neighborhoods suffering the effects of environmental degradation would respond to learning about what was happening around them.

That education needed to be taught on a campus full of trees, plants, ponds and animals reinforcing classroom learning. So, that’s what Diaz, who worked as an educator with Tree People, a Los Angeles nonprofit dedicated to wildland restoration, built.

Today, there is a second environmental charter high school campus and a middle school in Gardena and an environmental charter middle school in Inglewood. The four schools serve 1,840 students.

“When students learn about environmental injustice in their community,” Diaz said, “they want to do something about it.” When students present their ideas to school boards and city councils, adult leaders listen, she said. “Kids don’t realize that will happen.”

This type of education, Diaz said, inspires students to learn how to write persuasive letters to public officials. They are taught math and science skills so they can create and use statistics, surveys, data collection and observation. They learn the history of their community. They get to know their neighbors.

“Nature is a vehicle to teach students the tools and knowledge to be an advocate for their community,” said Tashanda Giles-Jones, director of the school’s environmental program. “Social justice and equity are built into everything we teach.”

Our Climate Change Challenge

Creating their own curriculum

California wants climate education for its students. Meet some of the teachers, schools and nonprofits making it happen.

Diaz has retired but sits on the board of Green Schools National Network, an organization that embraces the ECS approach with other schools.

Environmental science and biology classes are mandatory for every ECS student, but the linchpin of the climate curriculum is the 10th-grade Green Ambassadors environmental advocacy class, Giles-Jones said, where students learn the basics of community organizing and advocating for change, including written and oral arguments.

“We make sure the kids understand that sharing what they learn here is their responsibility. Our mission is to change the world.”

A 2016 ECS graduate, Tulsi Patel returned to the Lawndale campus after college to teach the advocacy class. She said she likes to teach in the school’s gardens, where student art and murals are scattered everywhere.

1

2

1. Student Julian Garcia, 16, holds up a jar containing the top of a pineapple that will eventually be planted on campus. to grow into an edible pineapple. 2. Jocelyn Hernandez, 16, shows one of the eggs she collected from the hens. (Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

“The school is very open to all different modes of using the outside space,” Patel said. “Students like to just sit outside and do their work as well.”

“We provide adequate space for nature to have a commanding presence,” said Eddie Cortes, who manages the school’s garden. “Everywhere you look, every corner of this school, there’s something going on. There is a giant spider web. Butterflies and bees zip around. There’s bird nests in the bushes.”

A Green Ambassador from last year’s class, Sophie Munguia-Rodriguez, said she grew up near the 405 Freeway, and her father, mother, sister and cousin all have asthma. The school, she said, motivates her to advocate for them. “Teachers don’t want us to ‘normalize’ injustice,” she said.

ECS schools depend on support from large local philanthropic organizations, including the Ahmanson foundation, plus a collection of nonprofit and corporate partners including the Nature Conservancy, Heal the Bay, the Bay Foundation and, surprisingly, Chevron Corp.

Of nearly $1 million in private support raised in the last two years, $840,000 came from foundations and corporate funders. Partnerships and private donations account for the rest. Most of the funds go to facilities and operations.

“Our kids are not hopeless,” said Patel. “Teachers are so invested in them. That makes them think about greater things and what can be done.”