Critic’s Notebook: How should television be defined nowadays?

- Share via

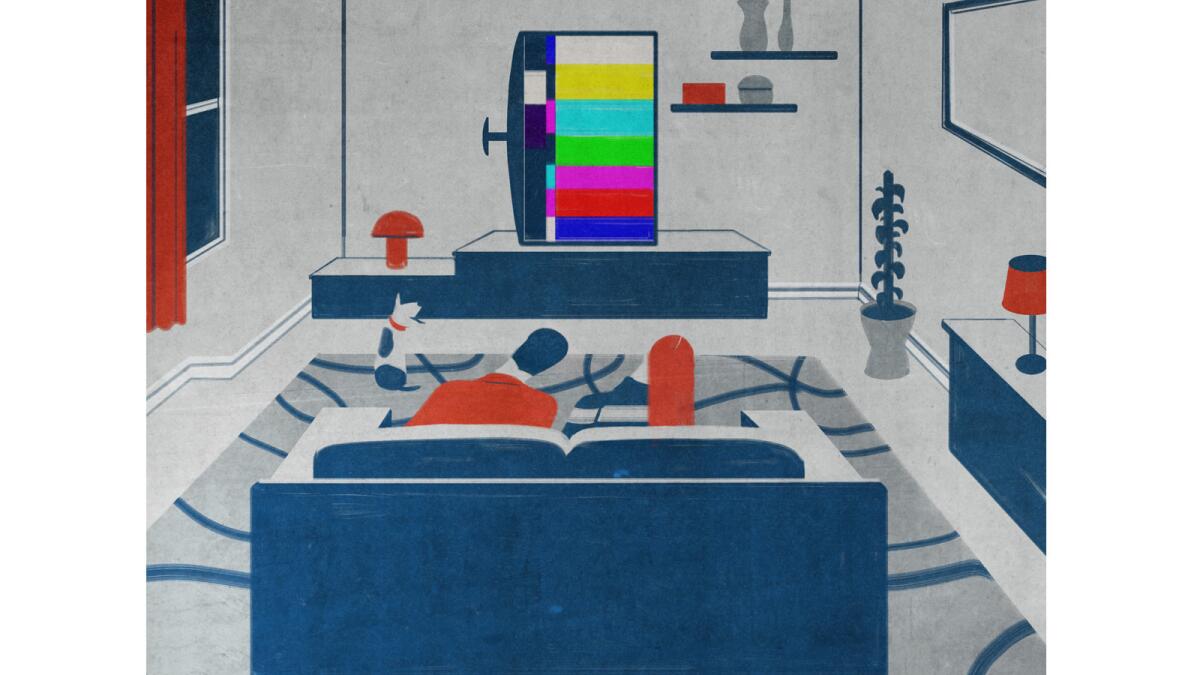

What is television? It seems a fair and timely question to ask, now that it’s coming at us from so many angles, on so many platforms, from so many producers.

Let’s begin near the beginning.

Once upon a time there was a thing called a television set. You knew where you stood with it, and you knew where it stood: in your house, in a fairly stationary, semi-permanent, prominent way — a box, sometimes a very big box, a piece of furniture. It didn’t hang on a wall, you couldn’t carry it around in your pocket or wear it on your wrist.

For many years, everything that came into a television set came out of the air, on invisible waves of light. Just how much TV you were able to see had to do with how the frequencies in your area were apportioned and how close you lived to a transmitter. There wasn’t much of it, compared to today, but there was still more than anybody could watch, even if, like Lyndon B. Johnson or Elvis Presley, you had three sets going at once.

Then television started coming through a cable as well, bringing dozens upon dozens of new channels to what was now just a figurative dial. Eventually it would also arrive through the telephone line or off a satellite or by way of a computer modem — and not into the squat single-purpose set of yore but into other machines that would become televisions just for a time and then go back to being computers, cellphones or a thing to play video games on.

Each new technology created new sorts of content, some of which bore only a cursory resemblance to the TV that preceded it and new sorts of business models that remodeled the older models. Now, for instance, HBO, a premium cable network, and CBS, one of the original broadcast networks, are making their wares available directly over the Internet — doing a Netflix — while Vimeo, the arty YouTube, is selling its first scripted series for $1.99 an episode (It’s called “High Maintenance,” and it’s about marijuana), as if it were iTunes or Amazon.

I once would have described television in terms of the formal qualities of its content: its standardized length, its episodic nature. And, as a professional critic, it seemed for a time necessary to limit the definition, almost as if one were defending “real” television against the barbarian hordes of terrible first-generation Web series — things that either tried to be like real TV and failed, like the twentysomething soap “Quarterlife” from the creators of “thirtysomething,” or that wrapped themselves prankishly in the medium, like “Lonelygirl5,” revealed to be nothing but a limp conspiracy thriller once it stopped pretending to be an actual vlog.

We have moved on from there into a world of video wonders. Now I am inclined to define television as any moving picture — at all — watched on any sort of screen not located within a movie theater. From a 30-second clip of a baby wombat to a fancy long-arc drama starring people whose other job is being a movie star, whether it was made by unionized professionals or rank amateurs, for fun or for profit, for crass reasons or noble purposes, art, garbage or garbage-art — I am happy to call it all TV. Whether you are shelling out for a full menu of premium channels and streaming sites or just consuming what you can pick up off the Internet for free, there is more to watch, and worth watching, than any reasonable person could ask for, or want.

Many distinctions, which I would call “real but imaginary” — that is, based on actual differences but mostly psychological in effect — have been applied to the medium through its history. In the unimaginably long time before cable, it was understood that VHF channels were qualitatively different from UHF (in L.A., the old home of public broadcasting and of Spanish-language). There was a perceived difference between network television and local television, between older networks like ABC and newer networks like Fox, between broadcast television and cable television, and between basic cable television networks and premium cable television networks. Those perceptions faded with use. Now we are reckoning with streaming services like Netflix and Amazon and Hulu making the jump from content distribution to content creation; they are already lining up for Emmys.

There is a certain amount of trauma that attends these changes. Television networks seem to regard one another as enemies engaged in a total war in which ratings get banner headlines and victory is claimed for dominating such and such a demographic at such and such an hour on such and such a day in such and such a week. They play a zero-sum game in which every pair of eyes tuned in to another network’s product is two fewer eyes you can take to the bank.

Regard the apocalyptic hubbub whenever a new brand of competitor edges into the Emmy race to challenge the last-established version of the establishment — first premium cable, then basic cable, now streaming systems like Netflix, each wanting a piece of the pie, each fighting for a seat at the table. The TV table.

As writers about television, we do tend to note the differing circumstances, economies, legal or practical constraints and degree of freedom that influence the kind and number of programs being made. As viewers, however, we do not — one channel is as good as another to a remote control. Obviously, there is a difference — many differences — between a piano-playing cat shot on a smartphone and a scripted program whose creation required hundreds of professionals and hundreds of thousands of dollars. You can’t judge one by the standards of the other. And yet, as I would declare it, each is television and, as a televisual life experience, potentially of equal value.

The Emmys, for their official part, have acknowledged that their universe is an expanding one, with awards for original interactive program (including crowd-sourced and/or user-generated narratives) and social TV experience (a synchronous or asynchronous social experience that supports audience communication and interaction for a linear program or an original interactive program) and expressly naming mobile (smartphone or tablet), computer, over-the-top set-top box or console, or Internet-connected/smart TV as platforms to be considered. There is an Emmy too for programs lasting less than 15 minutes — “Too Many Cooks,” anyone? — including those that are Web-based. (There is a chance for you too, “The Future With Emily Heller.”)

In 2014, and beyond, television is everything and anything that pours into whatever it is you watch it on. Without getting up once from the couch you might on a given evening watch a 1950s sitcom, a cartoon a teenager made in his bedroom, a TED talk, live broadcasts from the Senate or space, highlights of last night’s late-night talk shows, a concert video shot on a cellphone, a Korean soap opera, soccer in Spanish and half a dozen cats playing half a dozen pianos. Where the material originated can be interesting and even useful to know, as it is interesting and useful to know that the Mississippi River, which is partly fed by the Ohio River, which is partly fed by the Cumberland River, flows into the Gulf of Mexico or that the Amazon empties into the Atlantic. But it is all one watery body of water in the end.

So it is with television, a stew with ever more ingredients, in an ever bigger pot, and pleasure is limited only because you have to sleep, probably work and will most likely not live forever.

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.