Review: Joan Baez masters the art of the farewell concert

- Share via

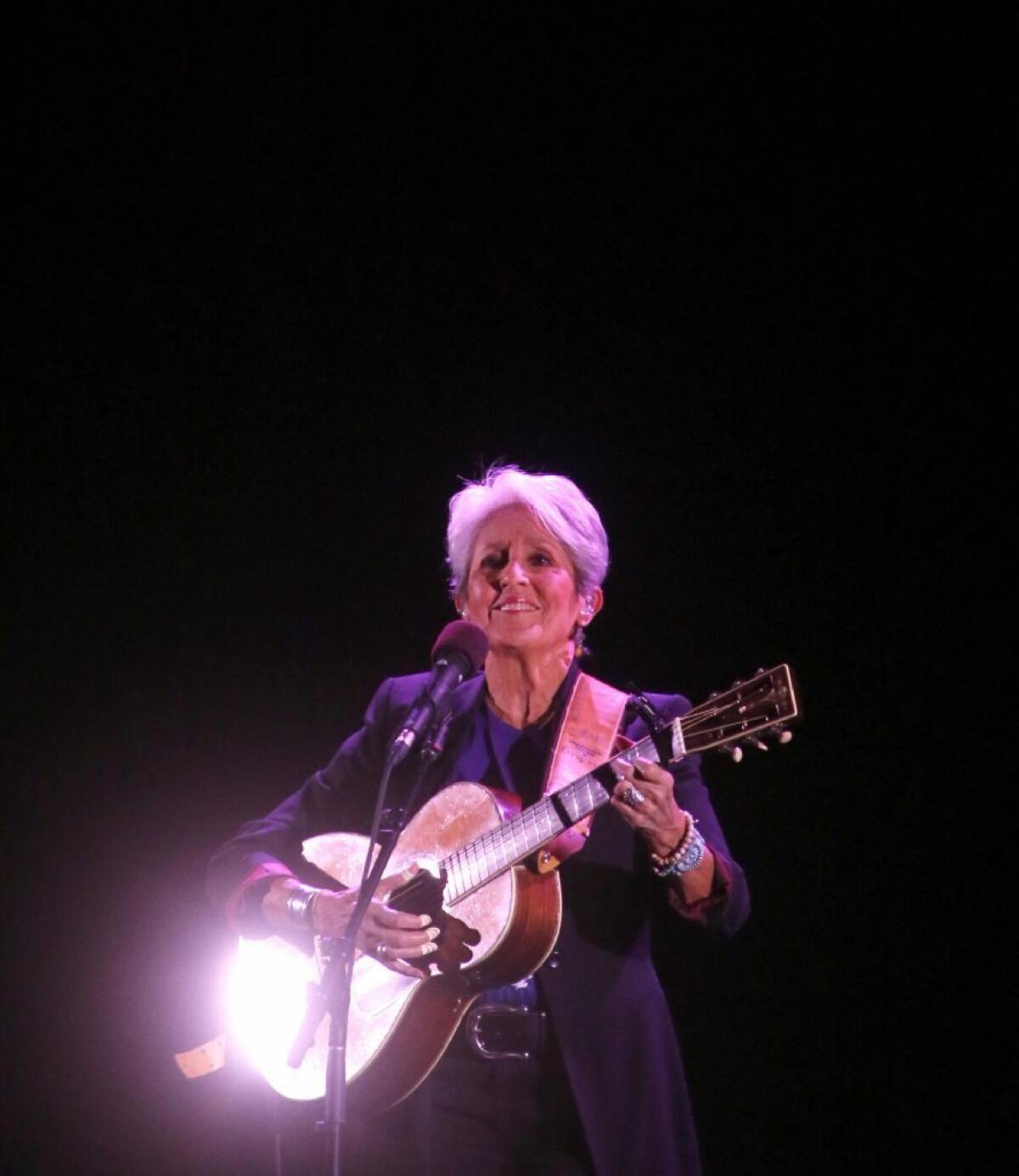

Joan Baez has commanded stages since 1959, back when she was a raven-haired teenager parting audiences’ hair with her piercing soprano in folk clubs around Boston.

When she announced late last year that she was retiring from touring, she said she got the idea from an unlikely source: her own voice.

“When I asked my first voice teacher… ‘When will I know when to stop singing?’ he said, ‘Your voice will tell you,’” Baez, 77, told The Times in 2017 around the time she was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

When Baez played to a sold-out crowd at UCLA’s Royce Hall on Saturday, it wasn’t obvious why she’s retiring — or why she should. Her guitar prowess was intact, as clean and crystalline as her skyscraping vocals once were. Her voice isn’t exactly shot, but she’s starting to notice its limitations, particularly when she goes long stretches between performances.

“Now it’s really wonderful. It’s a different voice, and I do whatever stuff I can cram into the right range,” Baez said in a phone interview a few hours before the Royce Hall concert. “There are compensating things, and as long as we stay smart about it, this [tour] can go on for a while.” (At the moment, Baez has no tour dates planned beyond next May, and Saturday’s concert was likely her last in Los Angeles.)

Baez treated the performance like any other, devoid of any cheap sentiment. There was no extended bow or teary fare-thee-well speech. Instead, she gave fans what they’ve always expected of her — impassioned performances and politics. (To answer your inevitable question: She kept President Trump out of the mix, save for a humorous aside at the end of “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.”)

Instead, she advocated for the rights of migrant workers [Woody Guthrie’s “Deportee (Plane Crash at Los Gatos)”] and the power of grass-roots organizing (“Joe Hill”). She also read a solemn passage she had written to reflect on the destruction of the deadly Southern California fires that wreaked so much havoc on the area.

The songs, especially a few from her new album, “Whistle Down the Wind,” told the story of her long journey. After a stark, opening rendition of “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” — one of a handful of Dylan songs she performed, “because they’re the best we’ve got” — Tom Waits’ “Last Leaf” seemed fitting, if a little comical.

“As in, me,” Baez joked with the audience. “OK, let’s face it — a lot of us here are the last leaf on the tree.”

Baez often performed with just her acoustic guitar, the way the world first discovered her, sweetening the melodies with her flamenco-like strum. That iconic voice is still a pleasure to behold, frayed lightly around the edges but resonant and relatable in a way that it wasn’t early on in her career. Now she imbues a chestnut like “House of the Rising Sun” with a bluesy melancholy that suggests a deeper understanding of the material.

Baez is on the road with her leanest but most dexterous band in recent memory. Dirk Powell was a virtuoso on many instruments, veering from subtle flourishes to show-stopping solos on piano, banjo, mandolin, bass, guitar and fiddle.

On understated backing vocals, Grace Stumberg restored some of the high notes Baez used to deploy like missiles, notably on “Forever Young.” And the presence of Gabriel Harris, Baez’s only child, on percussion lent an air of familial intimacy, particularly when she performed “Honest Lullaby,” which Baez penned in the ’70s as a meditation on the bond between mother and son (and her own mother).

Baez is still finding new ways into some of her signature songs. “Diamonds and Rust,” her devastating account of her love affair with Dylan, was luminous with its skeletal guitar accompaniment and the way Baez delivered the story with conversational grace.

Her interpretation of “Another World,” written by Anohni (formerly known as Antony Hegarty of Antony and the Johnsons), showcased a more experimental side of Baez’s craft. She tapped her guitar strings while fretting chords for a staccato rhythm, with Harris adding a vaporous undercurrent with jazz brushes. Baez said the lyrics synthesized her thoughts on the state of affairs: “I need another world / This one’s nearly gone.”

Baez is not alone in her conviction to go out on top. We’re saying goodbye to more and more of our icons these days, at least onstage, as Paul Simon, Elton John, Neil Diamond and George Clinton — all in their 70s — announced their retirements this year from decades relentlessly on the road.

Going into a farewell concert, it’s bittersweet to realize that it’s likely your last chance to hear an artist live one last time. Before a note is ever sung, we’re already under the spell of what their music has meant to us, the way it has soundtracked our lives. Some know when to hang it up while they’re ahead, while others — Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones, even 92-year-old Tony Bennett (coming soon to a California casino near you) — are still making the touring life work for them.

Last week, when the curtain rose to reveal a regal Joni Mitchell at the end of a birthday celebration in her honor, several fans at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion (including this critic) dabbed their misty eyes. Mitchell, clutching a cane and steadied by friends, never said a word, but as the cheers become deafening, it felt like it was our last glimpse of her. Talk about an anvil to the heart.

When asked earlier in the day about the spectrum of emotions she’s feeling on this tour, Baez sounded like the full brunt hadn’t hit her yet.

“I’m sure I will be upset,” she said. “I can’t pretend this is an easy thing to do. I love the shows.” And how are fans treating these farewell performances?

“There’s a lot of crying going on,” Baez said. “I figure I’m doing my job if they’re crying. I think part of it is, ‘Oh, my God. You can’t leave. Keep singing.’ And I get it. There aren’t that many people who do what I do and speak to the conditions of the world.”

Follow me on Twitter @jreedwrites.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.