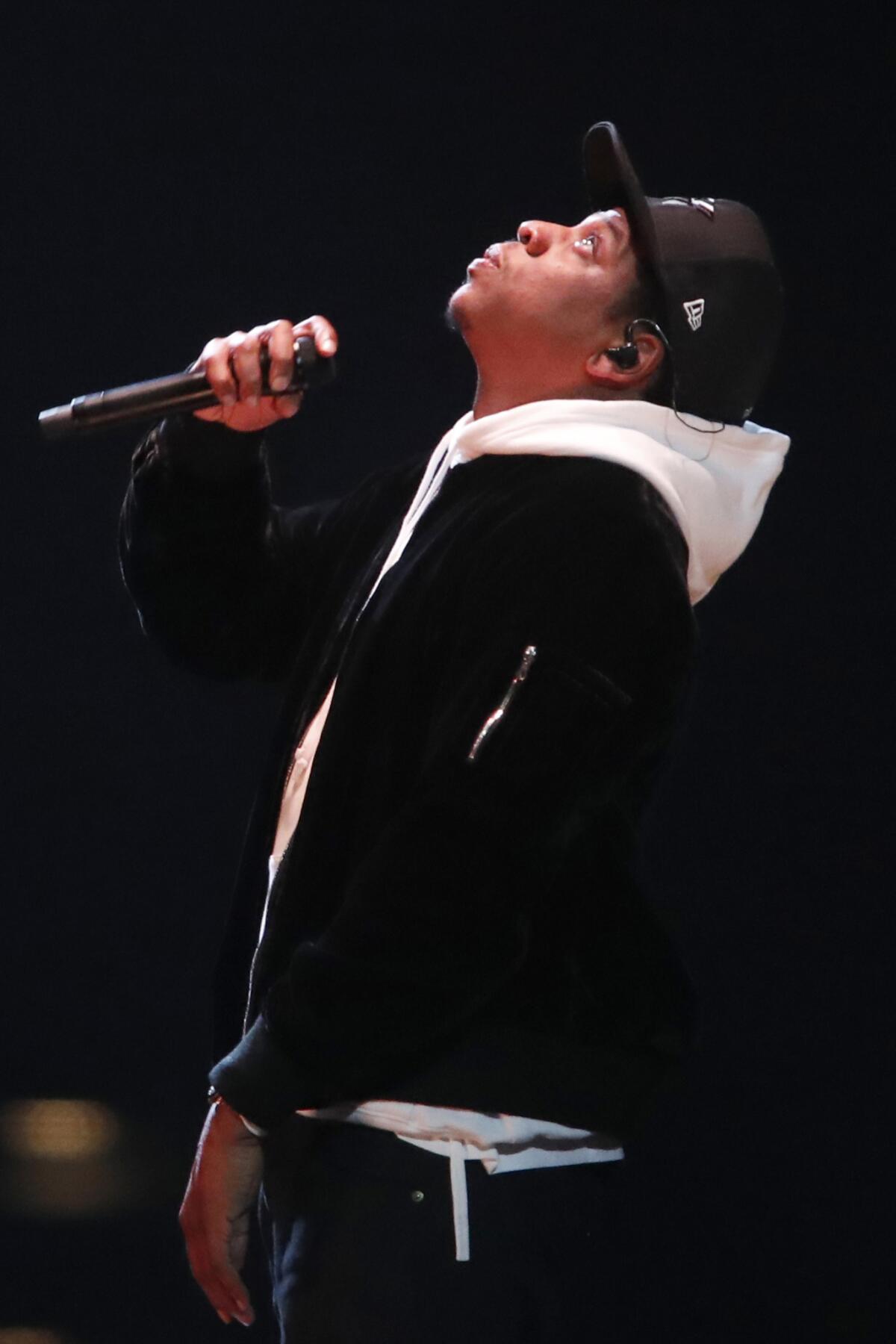

The Grammys’ hip-hop game-changers Kendrick Lamar and Jay-Z: An East Coast-West Coast contest

- Share via

Both men have sold millions of albums. Both have headlined the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival. And both made former President Barack Obama’s list of his favorite songs from 2017 — an especially meaningful achievement, perhaps, for two African American artists eager to share their political views (not to mention their scorn for the guy who now holds Obama’s old job).

So in a year when hip-hop might finally rule the Grammy Awards, it makes sense that Jay-Z and Kendrick Lamar would be the rap kings closest to victory come Sunday night.

With eight nominations, Jay-Z, the assured veteran, leads the field of contenders for music’s most prestigious prize, followed closely by Lamar, the upstart phenom, who has seven.

ALSO: The Age of Hip-Hop — From the streets to cultural dominance

All of Lamar’s nods put him in competition with Jay-Z in categories including album of the year, where his anthemic “Damn” is up against Jay-Z’s more intimate “4:44.” (They’ll also vie for record of the year, rap album, rap song, rap performance, rap/sung performance and music video.)

And Jay-Z’s eighth nomination? It’s for song of the year, for his album’s confessional title track, which marks only the second time in Grammys history — following Eminem in 2011 — that an MC has been nominated for the three biggest awards on one night.

If the overlap between Lamar and Jay-Z suggests that the two are cut from the same cloth, though, the work they’re being recognized for presents a different picture.

Both have undeniably changed the game, moving hip-hop into the mainstream (or keeping it there) as they’ve raised the bar for the kind of personal success available to a rapper. But each man followed a separate path to superstardom — and is using that platform in his own way.

Jay-Z’s risky (if successful) ‘4:44’ remakes hip-hop as a vehicle for middle-aged concerts.

In hip-hop, more perhaps than in any other genre, one’s hometown roots matter supremely, and for Jay-Z and Lamar that amounts to the latest iteration of a classic hip-hop rivalry between East Coast and West Coast.

Born and raised in Brooklyn, Jay-Z, 48, has long drawn on New York’s popular mythology as a place for hustlers and braggarts; not for nothing did he conjure echoes of Frank Sinatra by having Alicia Keys sing the city’s name over and over in “Empire State of Mind,” his 2009 tribute to that “concrete jungle where dreams are made of.”

And that idea of the town is still alive in his music (even if he and his wife, Beyoncé, seem to spend most of their time these days in Los Angeles). In “Marcy Me,” a slow-rolling cut from “4:44,” Jay-Z vividly describes the housing projects where he grew up — part of the grimy “old Brooklyn,” as he puts it, not the developer’s haven that now “feel[s] like a spoof.”

Thirty-year-old Lamar, a proud Compton native, fills his songs with just as many references to his specific surroundings, as in his song “Element,” from “Damn,” in which he mentions Tam’s Burgers and Stockton Street, where he once danced on the roof of the now-shuttered Compton Swap Meet in the music video for his song “King Kunta.”

With early endorsements by Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg, Lamar emerged around the time of his major-label debut, 2012’s “good kid, m.A.A.d city,” as an heir to the gangsta-rap legacy that began in the 1980s with Dr. Dre’s Compton-based N.W.A.

Yet Lamar’s modification was to present himself as a conflicted observer of gang violence rather than an active participant — a shift in perspective from N.W.A and also from Jay-Z, who’s never shied from his past as a drug dealer. That’s a crucial distinction: For Lamar, as for others in his generation, drugs and gangs aren’t sources of pride or community; they’re reasons to question authority.

Sonically, too, Lamar has worked to advance the West Coast’s signature sound. Though it still features the Dr. Dre formula of heavy beats and funky bass, “Damn” expands gangsta rap’s palette with slick synths and psychedelic guitar.

Kendrick’s ‘Damn’ expands gangsta rap’s palette with slick synths and psychedelic guitar.

Jay-Z, for his part, isn’t uninterested in daring production. His work in the early 2000s with Timbaland and the Neptunes — classics like “Big Pimpin’” and “I Just Wanna Love U (Give It 2 Me)” — still carry a whiff of adventure.

But with “4:44” the rapper took a determinedly old-school approach, working with the producer No I.D. to build the tracks around dusty samples of tunes by Nina Simone, Donny Hathaway and the Clark Sisters; his rapping too is some of the plainest, albeit most effective, he’s ever done, with a clear emphasis on being understood on a word-for-word basis.

The tension between tradition and innovation is a familiar storyline at the Grammys, as we saw in 2017 when Adele went up against Beyoncé in the major categories.

And it’s in play elsewhere among this year’s nominations. Lamar and Jay-Z’s competition for album of the year, for instance, includes Lorde, the boldly youthful New Zealand singer and songwriter, and a pair of clever R&B revivalists in Bruno Mars and Childish Gambino.

Yet it’s not right to conclude simply that Lamar is disrupting the established order embodied by Jay-Z.

Sure, Jay-Z has won 21 Grammys, whereas Lamar lost album of the year both times he was previously nominated for it — one indication of the Recording Academy’s hard-wired tendency to reward proven winners.

In a sense, though, it’s actually Jay-Z’s maturity, and the way he addresses it on “4:44,” that makes him an outlier. With deeply felt songs about his troubled marriage and his failings as a father, the album represents Jay-Z’s risky (if successful) attempt to remake hip-hop as a vehicle for middle-aged concerns, as opposed to the challenges and paranoia that preoccupy Lamar on “Damn.”

In his hit single “Humble,” nominated for record of the year against Jay-Z’s “The Story of O.J.,” Lamar isn’t stressing his own humility; he’s warning away folks who might wrongly assume they can step to him.

Where the two come together is in their thinking about race and about the value — as well the cost — of black achievement in Donald Trump’s America.

In his song “Yah,” Lamar raps about being targeted by the conservative pundits at Fox News who “wanna use my name for percentage.” Jay-Z, meanwhile, lays out his plans to pass on his wealth to his children as a means of combating the institutional bigotry he’s certain they’ll encounter as they grow up.

That both rappers are in contention for the music industry’s crowning accolade — and with no fear of being pushed aside by Steely Dan or Robert Plant or some other past-it Grammy fave — is proof of progress in that fight, at least for anyone who wants awards shows to properly reflect what matters in culture.

With that in mind, maybe who wins Sunday is beside the point. The real triumph was the space hip-hop gave these diverse voices to flourish.

Twitter: @mikaelwood

ALSO

The Grammy Awards at 60: What a long, strange trip it’s been

Julia Michaels on taking ‘Issues’ — and her issues — to the Grammy Awards

After losing steam, the Stereotypes almost hung it up — now they are up for producer of the year

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.