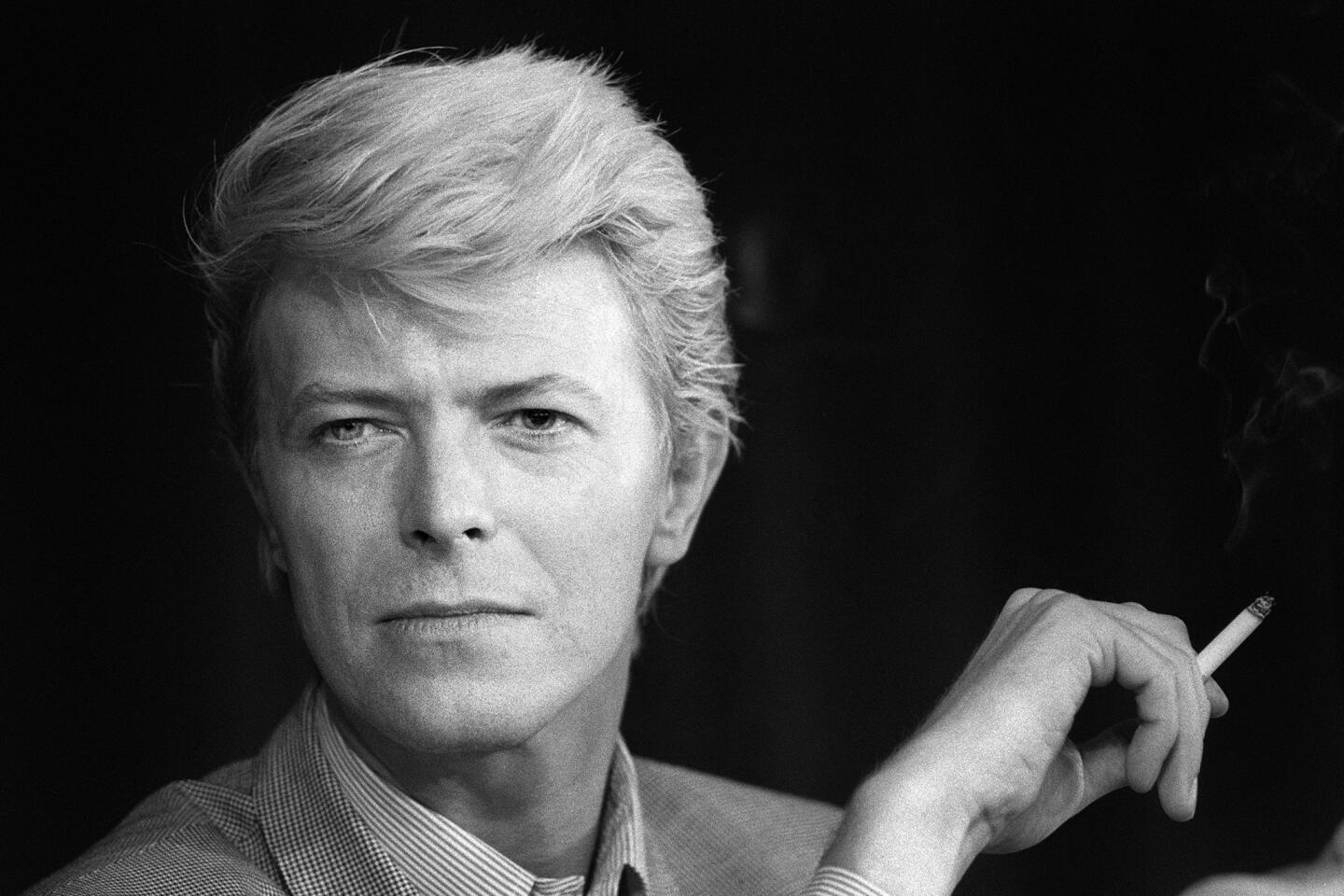

Appreciation: David Bowie was a vivid and gentle presence who never stopped exploring

Illustration by Ken Fallin.

- Share via

He was just like us, David Bowie.

Sounds wrong, doesn’t it? What could we have in common with the glamorous bundle of hangers? Which of us could find the hairline between genders and camp there for years? Could we make leg warmers look fabulous? Could there be any commonalities between regular folk and this alien who loved the world?

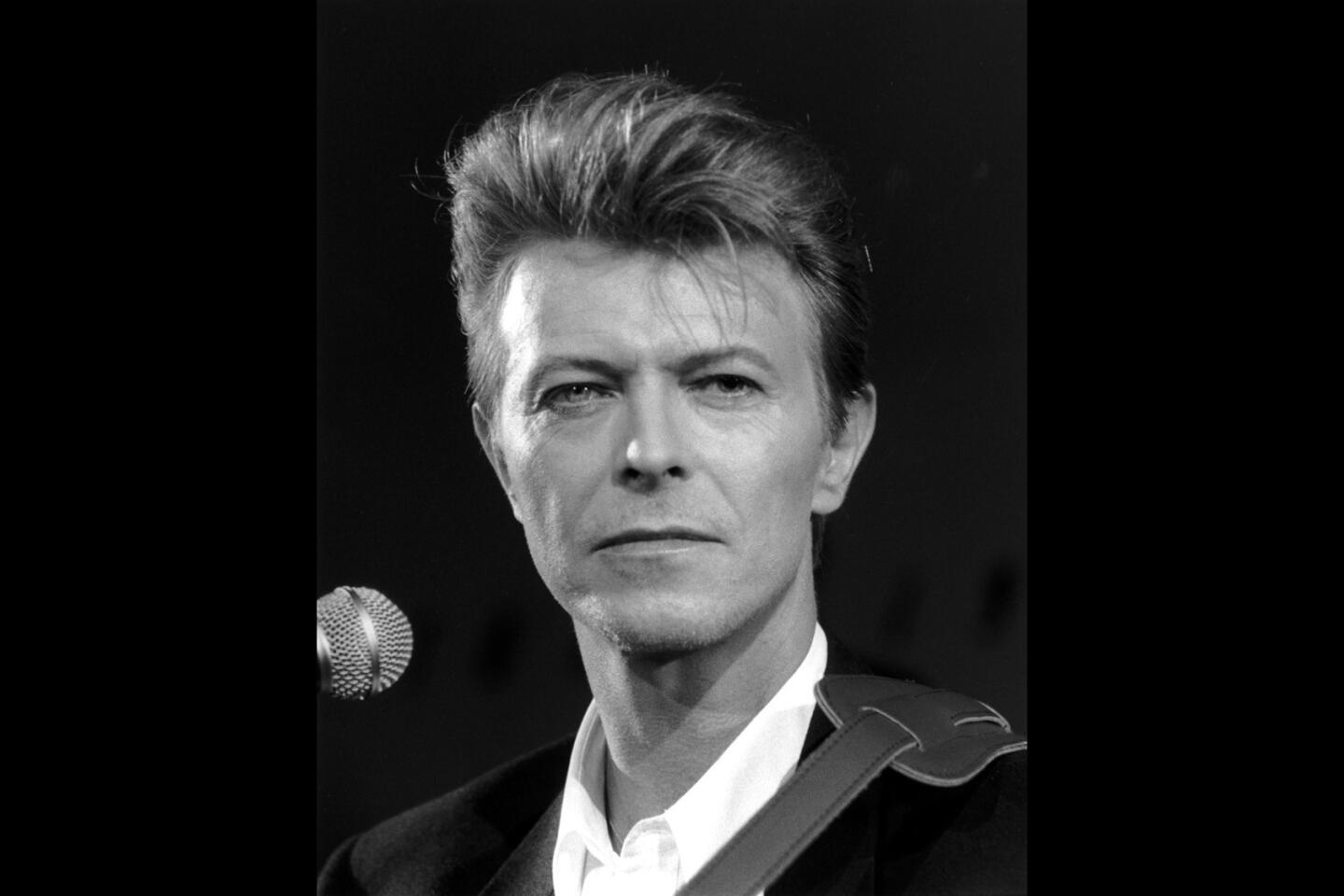

Look at the end or the beginning and you’ll find the key. You’ll see a disciplined, almost illogically sweet man who paid exquisite attention to everything. Bowie was equally fascinated by the mundane and the bizarre, the accidental charges and the planned, grinding make-work. He made himself from both.

DAVID BOWIE: A life remembered in 10-plus articles >>

Of course, David Bowie was nothing like any of us beyond two tendencies: He worked like a dog, and he paid attention.

When his career began, roughly 50 years ago, he was just plain David Jones, known professionally as Davie Jones. There ended up being another such Jones, in the Monkees, so a new name was needed. The David Bowie futzed with variations of folk and tweaked the idea of a music hall dandy, loading it with bits of hippie culture, without finding a successful hybrid.

The songs, though, started coming early: “Space Oddity” (1969) and “The Man Who Sold the World” (1970). His stylistic range started wide, which is where it stayed. “The Laughing Gnome” (1967) is a descendant of music hall comedy in England and usually mocked. Not hard to see why. Bowie chim-chim-cherees and trades lines with a studio chipmunk voice, making puns on the word “gnome.” You don’t need to hear more than half of it at most. But that Bowie never goes away — in 1986’s “Labyrinth,” Bowie plays Jareth, the Goblin King, essentially performing “The Laughing Gnome” again, except this time he and his gnomes come perilously close to rapping.

And all of this is more baffling if one tries to connect that Bowie to Ziggy Stardust, the character he found in 1972, taking him from intermittent chart presence to superstar. Slightly tweedy before Ziggy, Bowie was styled by his wife, Angie, into a chromatic exclamation point. From his new American friend, Iggy Pop, Bowie borrowed four out of five letters for a new stage name and a sense of uninhibited sexuality. With Iggy, that physicality read as dangerous, but Bowie tended to make things look elegant and fun; he had no love of shock or aggression. In a 1984 interview with People, Pop said “David was actually very turned off by the onstage violence I got into.”

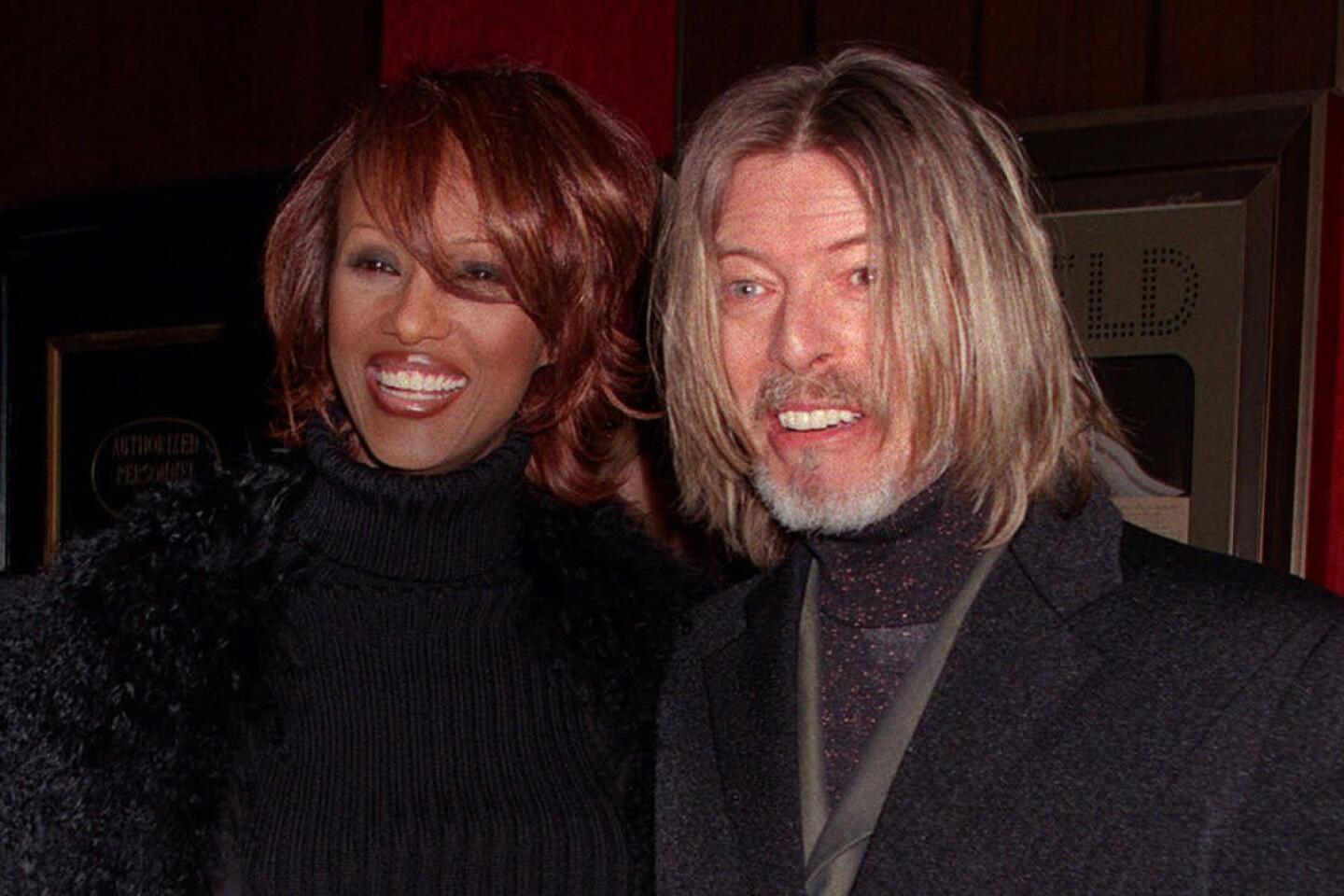

Then there was his nearly 24-year marriage to Somali American Iman Mohamed Abdulmajid, a model who went on to build one of the first cosmetic lines aimed at women of color, a major commercial success. There was his seemingly out-of-the-blue dressing-down of MTV in 1983 for the network’s lack of racial diversity in programming.

One vital aspect of his public life with us was an openness to other people’s work. He was constantly being tagged — usually by himself — as a magpie. (He used the term “collector” in an early television interview.) But after he’d pick something up — German rock of the mid-’70s, American soul, drum and bass — he’d usually put it back down after a year or two, like a friendly neighbor returning a book you’ve lent him and forgotten about.

Which brings us, out of order, to the present. Not the hideous present but the recent past. When I spoke to saxophonist Donny McCaslin about the making of Bowie’s latest and last album, “★” (spoken as “Blackstar”), he told me they talked constantly about books. A few years before that, I had the unexpected honor of interviewing Iman, who unprompted began talking about how much Bowie loved to read and how they had to make up fake names so the mailman wouldn’t know who all the Amazon deliveries were for.

Move sideways from that comment and scroll back to the early aughts. Once settled in Soho, Bowie and Iman were two of New York’s most public famous people. It feels insane to write these words, but I saw him so often on the streets that I stopped taking note of it. He always seemed to be coming out of a museum or a bookstore or going into his office on Chrystie Street. It was one reason so many of us, especially those living in New York, could end up thinking he’d always be around.

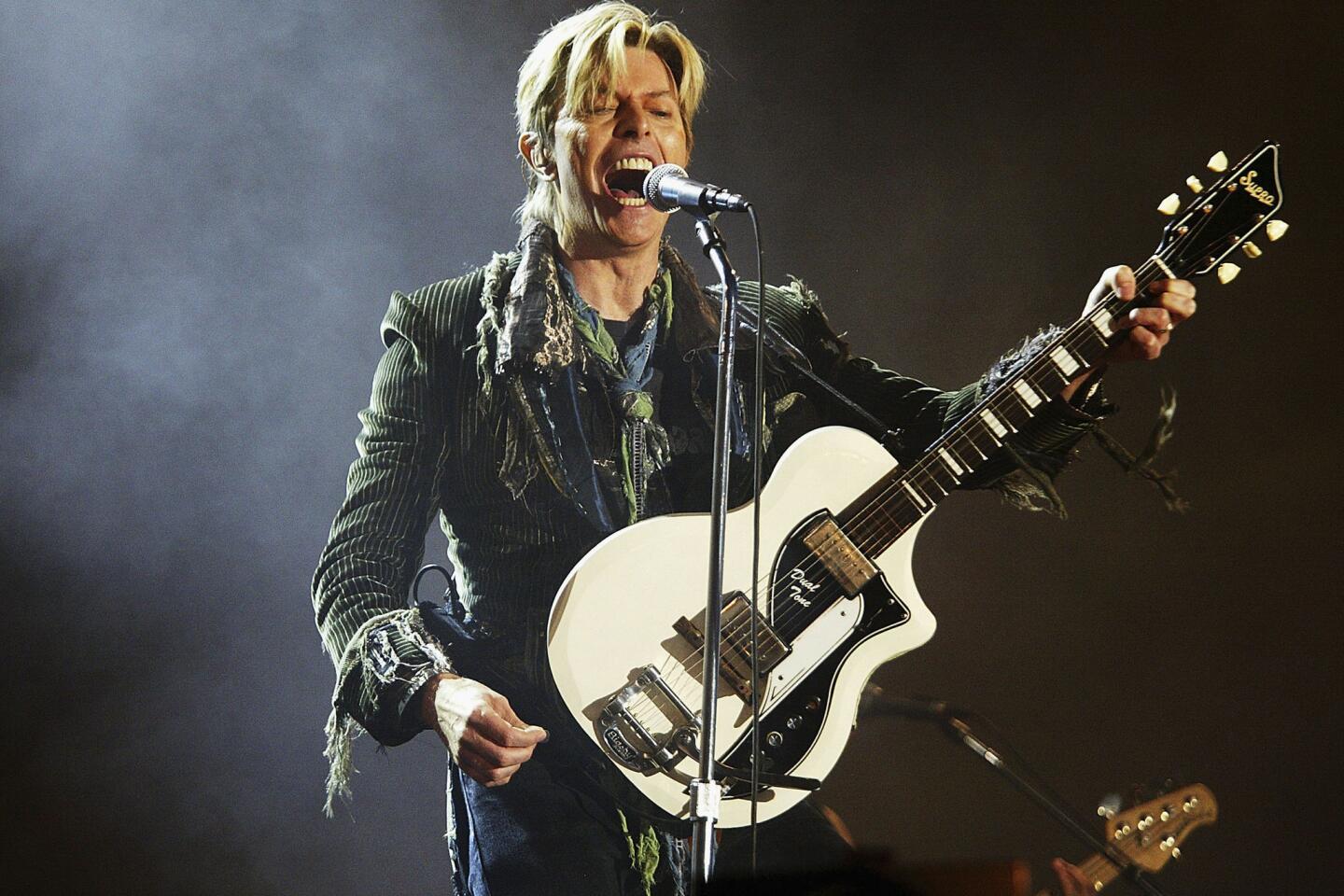

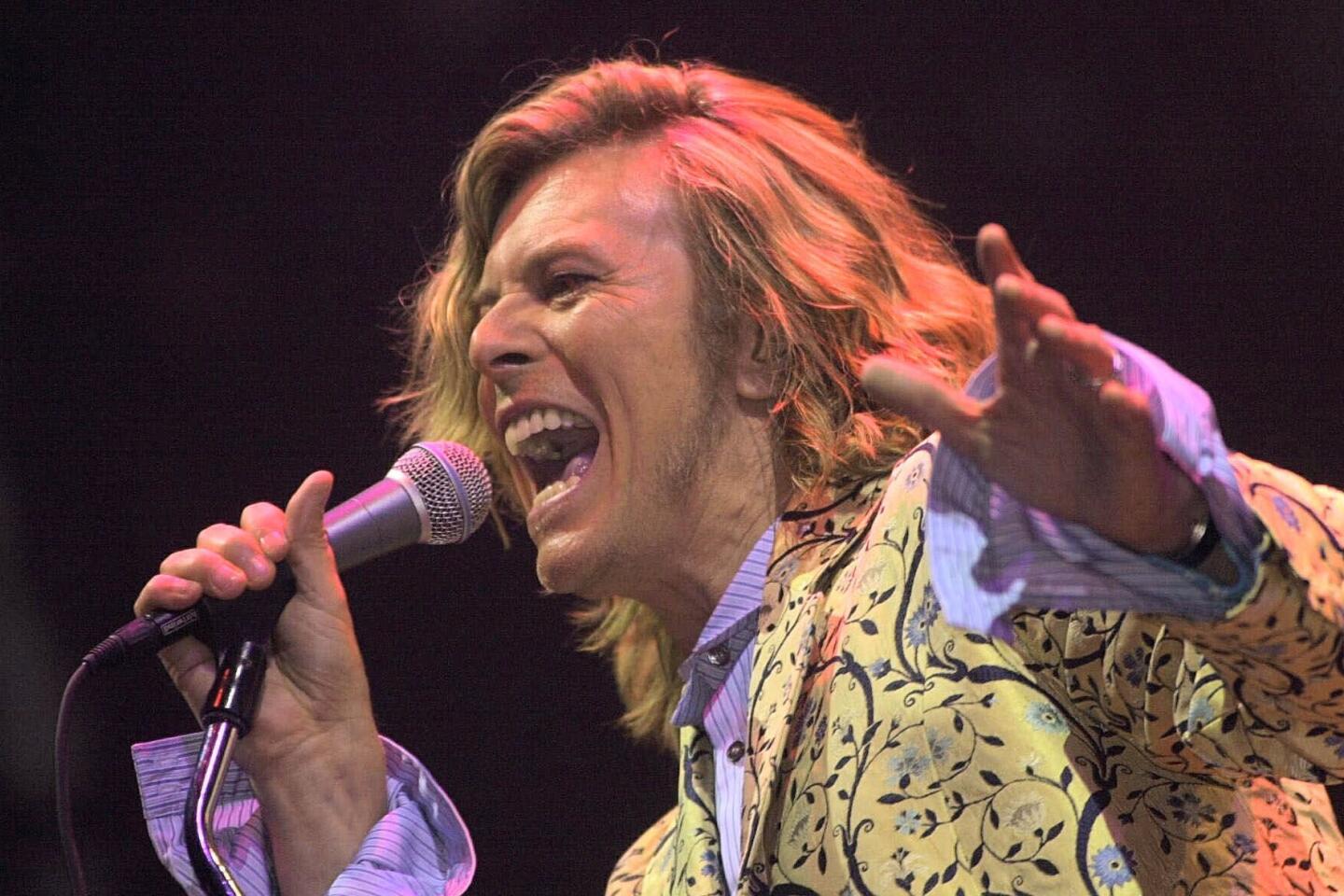

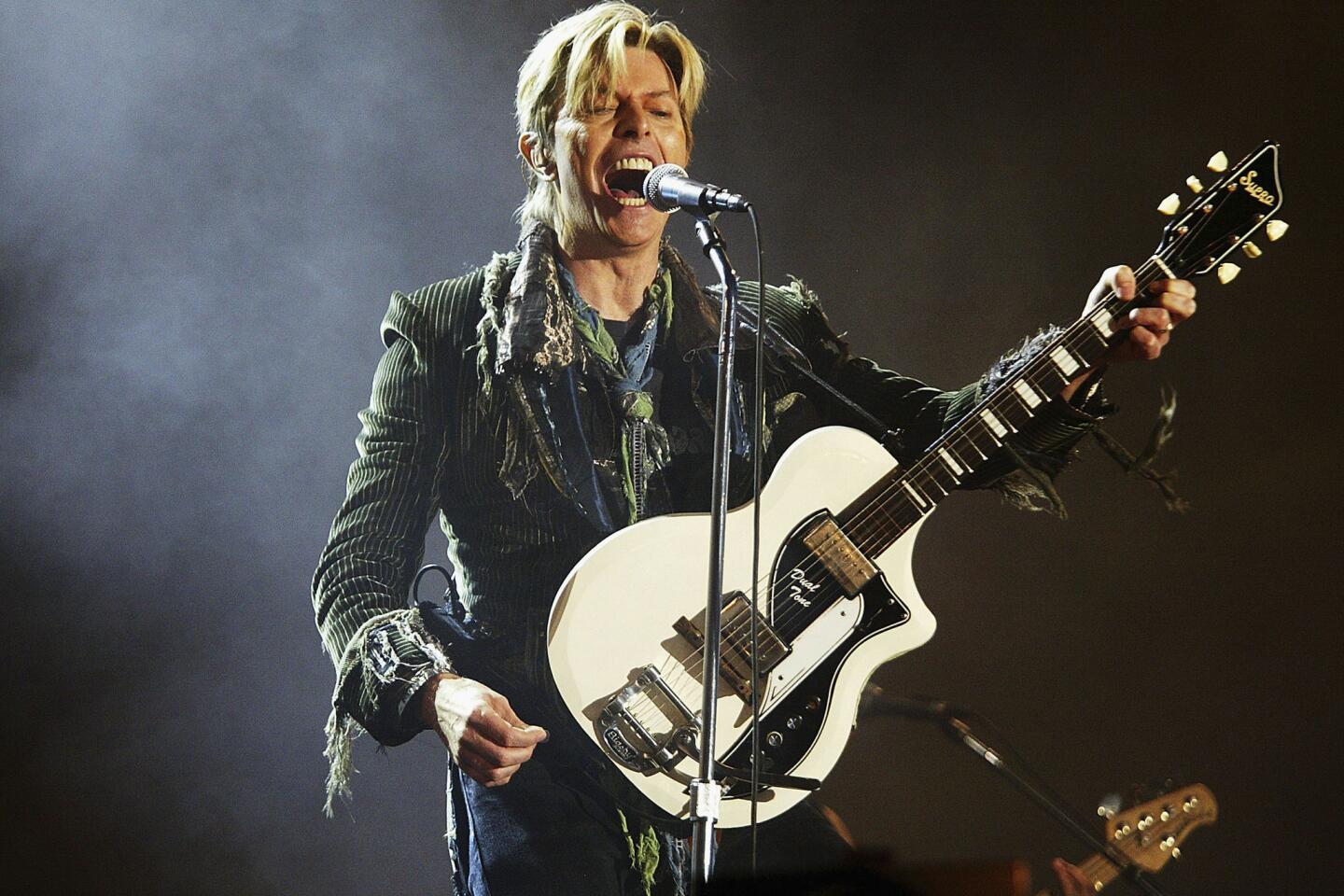

He was always around, and for most of the time, putting out material, appearing in movies, being David Bowie. As vivid as the ‘70s were, with Ziggy Stardust and the Thin White Duke and Berlin Bowie rolling around, Bowie spent the longest period of all being a public student with no fixed target. He stopped the full-on theatrical immersion and let us watch him be as curious.

There was only a vague character at the center of 1983’s “Let’s Dance” — perhaps an amateur boxer based in Miami? Maybe. After that, Bowie was just a working artist unafraid of bombing and then turning around and dropping something worthwhile.

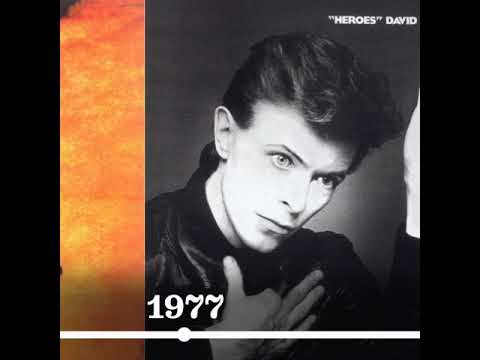

A timeline of David Bowie’s studio releases

His collaboration with Queen on “Under Pressure” is almost its own genre of music, some kind of skeletal stadium disco that addresses the human condition in an entirely sincere, almost awkward way. His cover with Mick Jagger of “Dancing in the Street” is an adorable night out with a friend that has no reason to exist. Except that it reminds us Bowie wasn’t flustered by failure, and here is how he never calcified. Plenty of artists had a hot seven-year streak, and most of them became embittered traditionalists. Bowie left this world seeing small live shows and finding a jazz quartet that channeled electronica.

In 1980, he was delicate and unpredictable on Broadway in “The Elephant Man.” Three years later came “The Hunger,” Bowie playing a goofball vampire in a movie with a straight-to-VHS horror aesthetic. High, low: whevs. In both cases, his moral bubble remained level. Empathy was more interesting to Bowie than menace, hence his time as the most peaceful alien until E.T.

One scene from Nicolas Roeg’s 1976 film “The Man Who Fell to Earth” does a decent job of summing up Bowie’s gentle brand of exploration. Being an alien, Bowie has to insert lenses over his native cat eyes — y’know, other atmospheres and all that — to appear human. When Candy Clark watches him remove the lenses, revealing those yellow eyeballs, she screams as if being attacked. Bowie just stands there, doing nothing. This bemused traveler shows up in many interviews, where Bowie is being asked to provide salacious weirdness. Time after time, he disappoints. He returns, over the years, to many variations of “Well, this is interesting, isn’t it?” When one interviewer asked him about the “alienation” he heard on “Low,” Bowie took no visible offense and patiently responded, “Well, it’s a new language.”

How many times could Bowie have said that? Even when borrowing from African American soul in the ‘70s, working with a young singer named Luther Vandross and Roy Ayers’ drummer, Dennis Davis, Bowie didn’t render “Young Americans” as a soul album. We hear the Bowie filter, processing a new batch of material, a trace of how he heard. Before long, he used it to mulch Kraftwerk and Neu! and Brian Eno, with Eno himself doing some of the mulching.

This may be why cultural appropriation feels different with Bowie — he immerses himself entirely, while highlighting his own idiosyncrasies. He never seemed like a carpetbagger because he rarely lost himself in the work.

He was obviously comfortable being an actor and even admitted to being one while appearing — in a jittery state — on “Dick Cavett” during the ‘70s. If so, he was often the most charming bad actor in pop. We always knew it was him. Which would make sense with his love of hybrids. He would be an unusually physical actor when in plays or movies but not a particularly emotional one. He would be a theatrical pop star but not a cathartic one.

Where so many aging rock stars hand out a weird, barely believable line about not listening to “the crap on the radio,” Bowie was right there with us, listening to new music, sifting through the digital bins.

He rejected the term “rock ‘n’ roll” entirely, so he had to fulfill some unnamable role. And maybe he never told us what it was, and never chose, because it was all worthwhile.

MORE:

Full coverage: David Bowie’s life and career

David Bowie: The Man Who Changed the (Music) World (1947-2016)

Remembering David Bowie through his 100 favorite books

Mikael Wood review: David Bowie looks far beyond pop on jazz-inspired ‘Blackstar’

From the Robert Hilburn archives: David Bowie spends the ‘80s convincing us he’s just a normal guy

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.