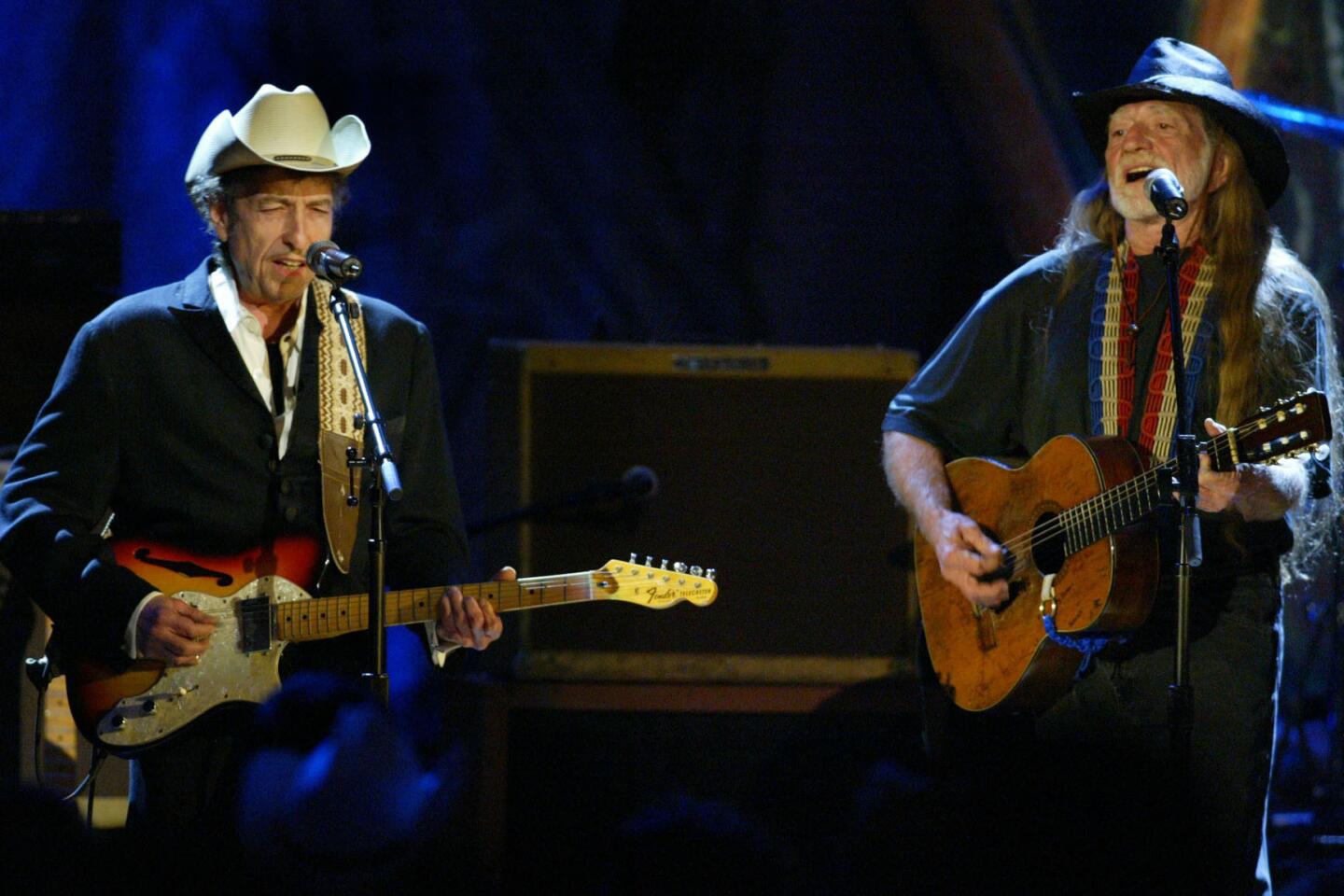

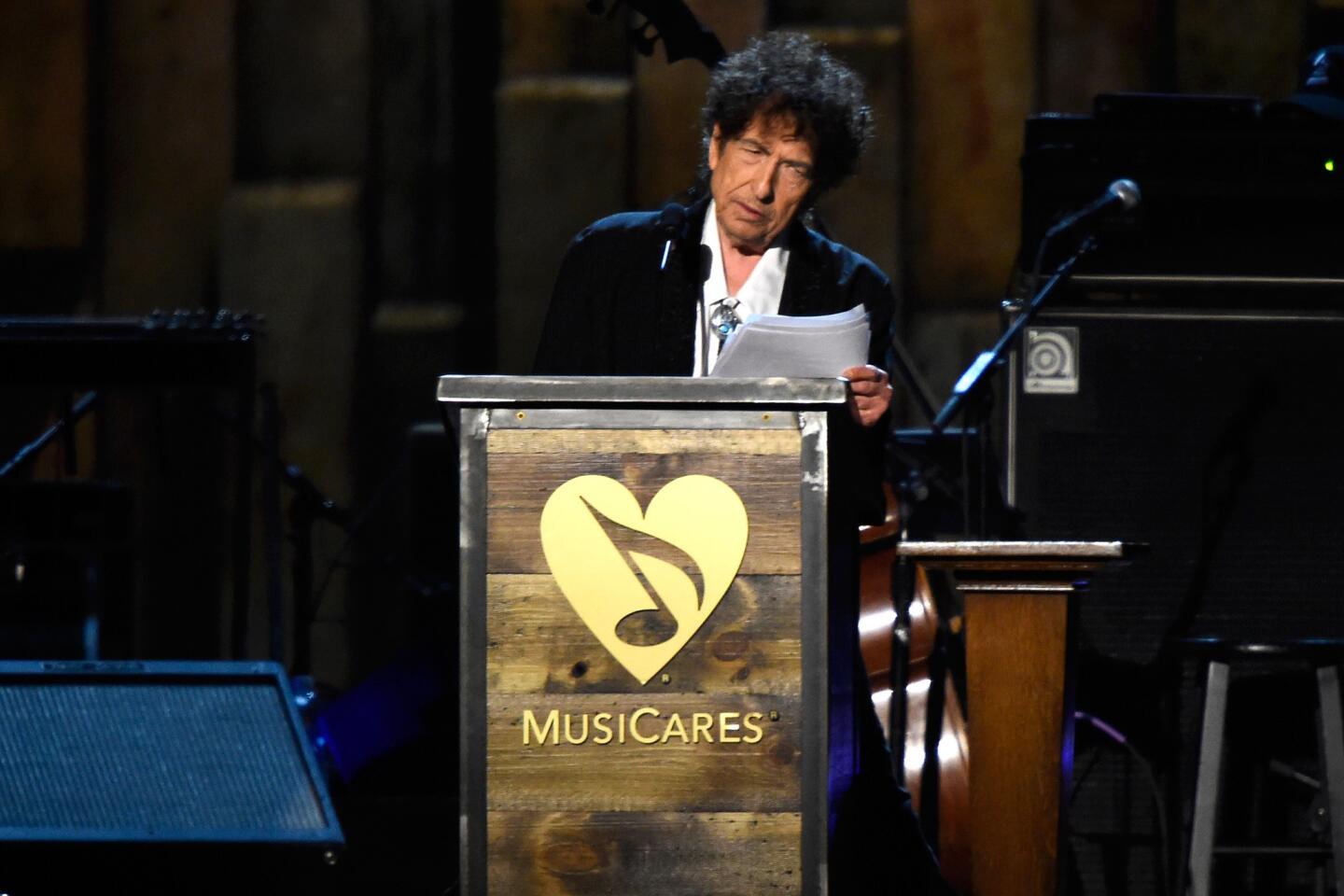

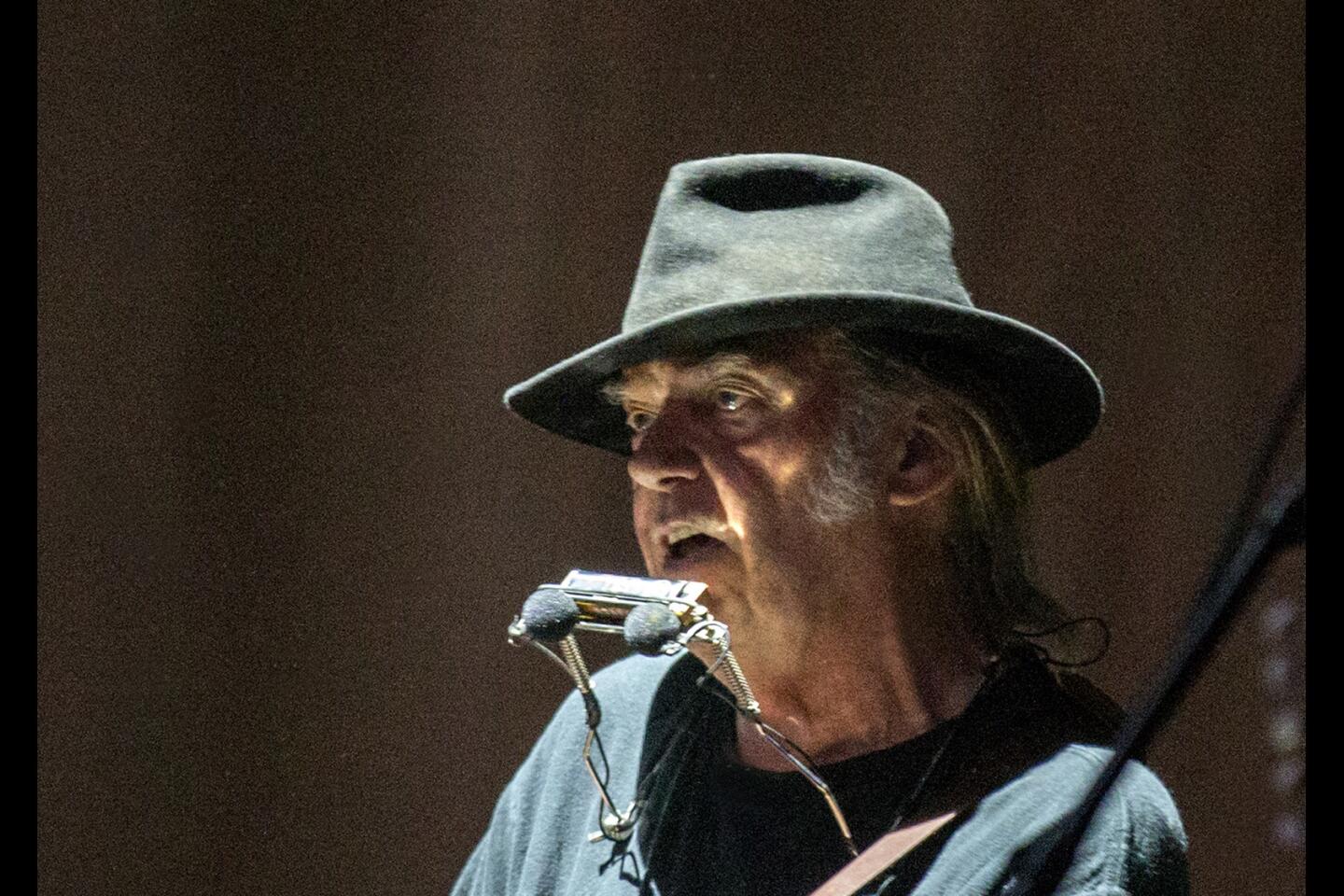

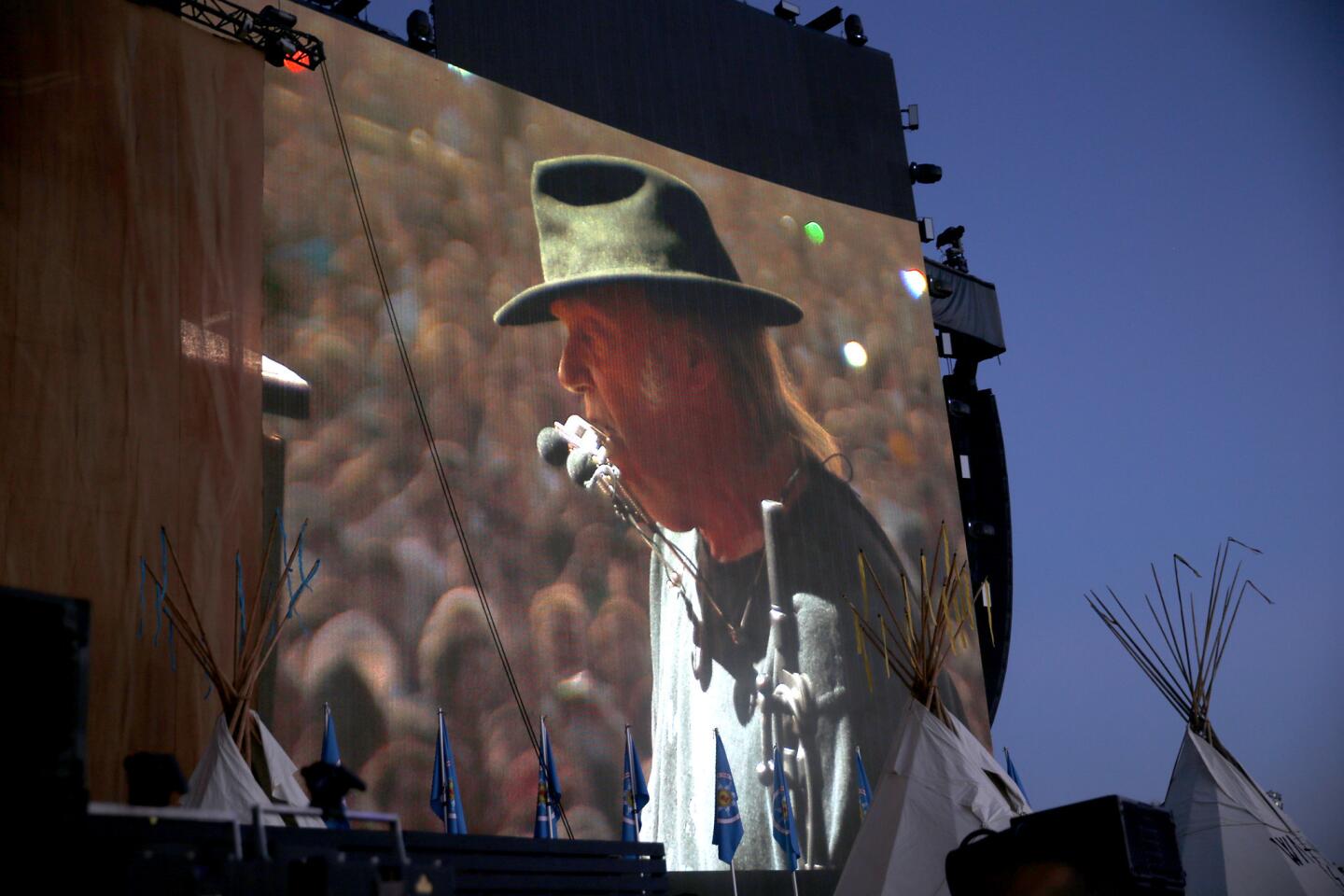

From the Archives: ‘I always admired true artists, so I learned from them’: When the enigmatic Bob Dylan opened up in 2004

- Share via

Reporting from Amsterdam — Editor’s note: In what was considered a “radical” choice, Bob Dylan was announced as the winner of the Nobel Prize in literature on Oct. 13, 2016. Read the story here. In a rare long-form print interview, the singer sat down with then-L.A. Times pop music critic Robert Hilburn in 2004 to discuss his influences, lyrics and his film “Masked and Anonymous,” which he co-wrote and starred in. This story originally ran in The Times on Aug. 4, 2004.

“No, no, no,” Bob Dylan says sharply when asked if aspiring songwriters should learn their craft by studying his albums, which is precisely what thousands have done for decades.

“It’s only natural to pattern yourself after someone,” he says, opening a door on a subject that has long been off-limits to reporters: his songwriting process. “If I wanted to be a painter, I might think about trying to be like Van Gogh, or if I was an actor, act like Laurence Olivier. If I was an architect, there’s Frank Gehry.

“But you can’t just copy somebody. If you like someone’s work, the important thing is to be exposed to everything that person has been exposed to. Anyone who wants to be a songwriter should listen to as much folk music as they can, study the form and structure of stuff that has been around for 100 years. I go back to Stephen Foster.”

For four decades, Dylan has been a grand American paradox: an artist who revolutionized popular songwriting with his nakedly personal yet challenging work but who keeps us at such distance from his private life -- and his creative technique -- that he didn’t have to look far for the title of his recent movie: “Masked and Anonymous.”

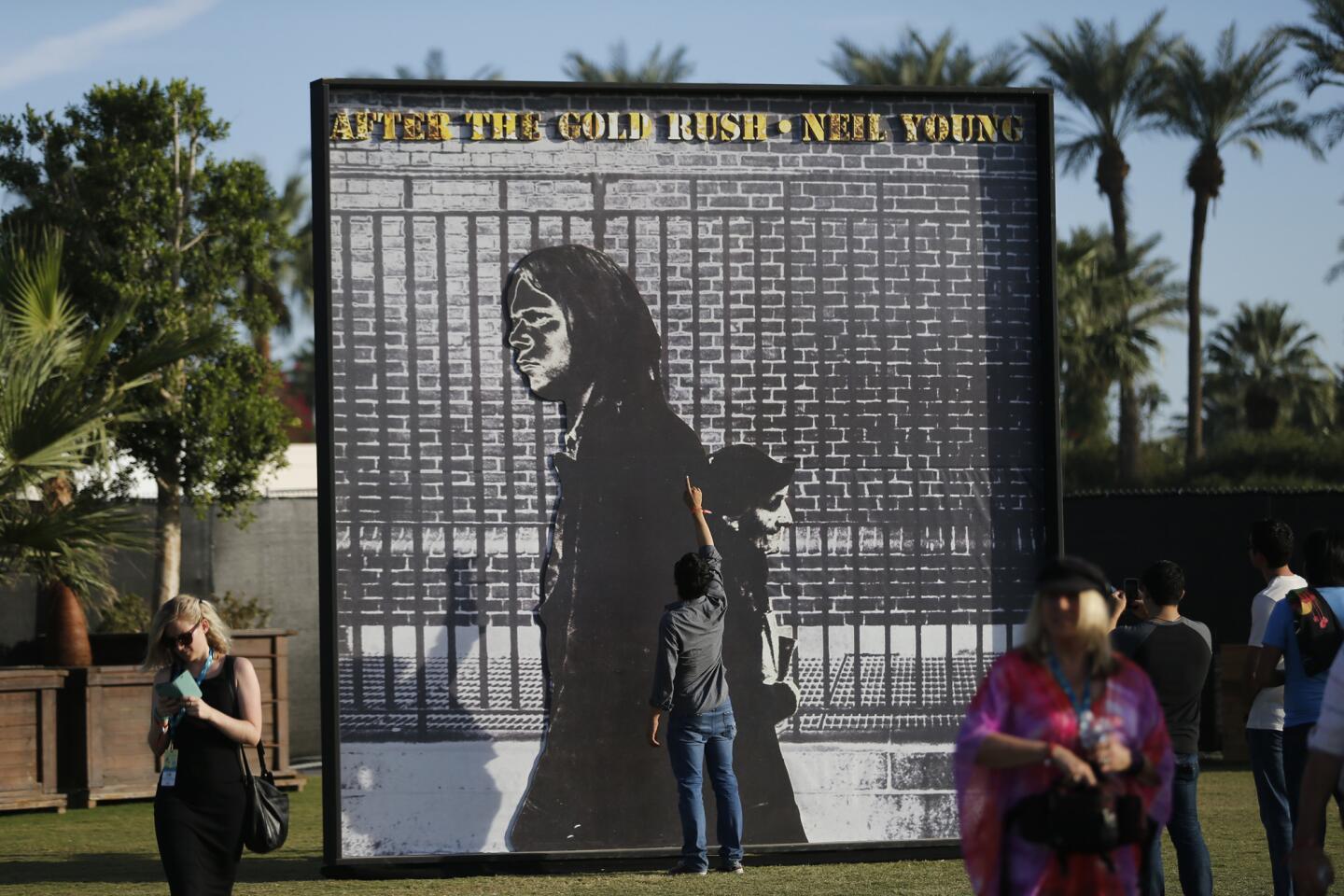

A brief look at the catalog of Bob Dylan.

Although fans and biographers might read his hundreds of songs as a chronicle of one man’s love and loss, celebration and outrage, he doesn’t revisit the stories behind the songs, per se, when he talks about his art this evening. What’s more comfortable, and perhaps more interesting to him, is the way craft lets him turn life, ideas, observations and strings of poetic images into songs.

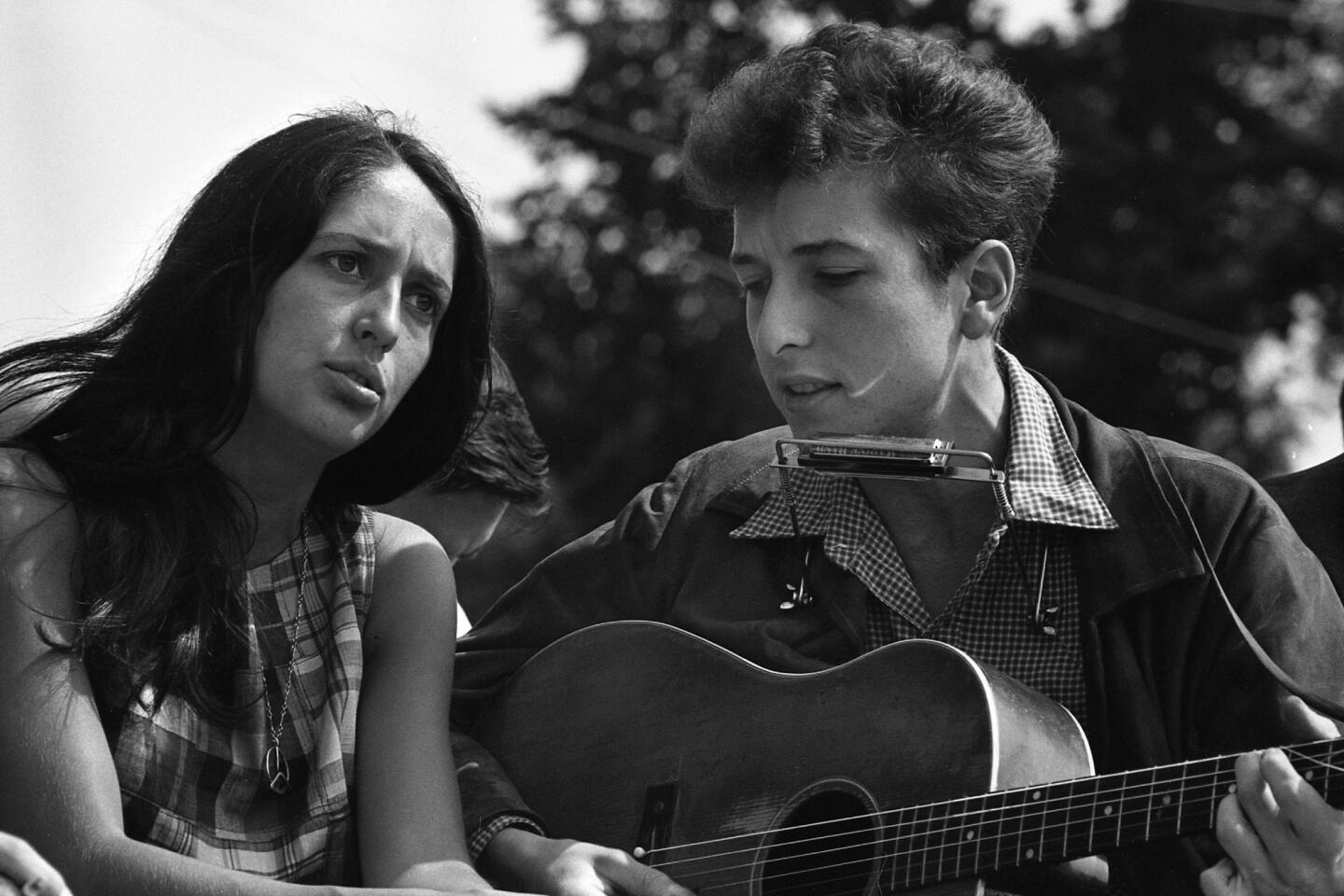

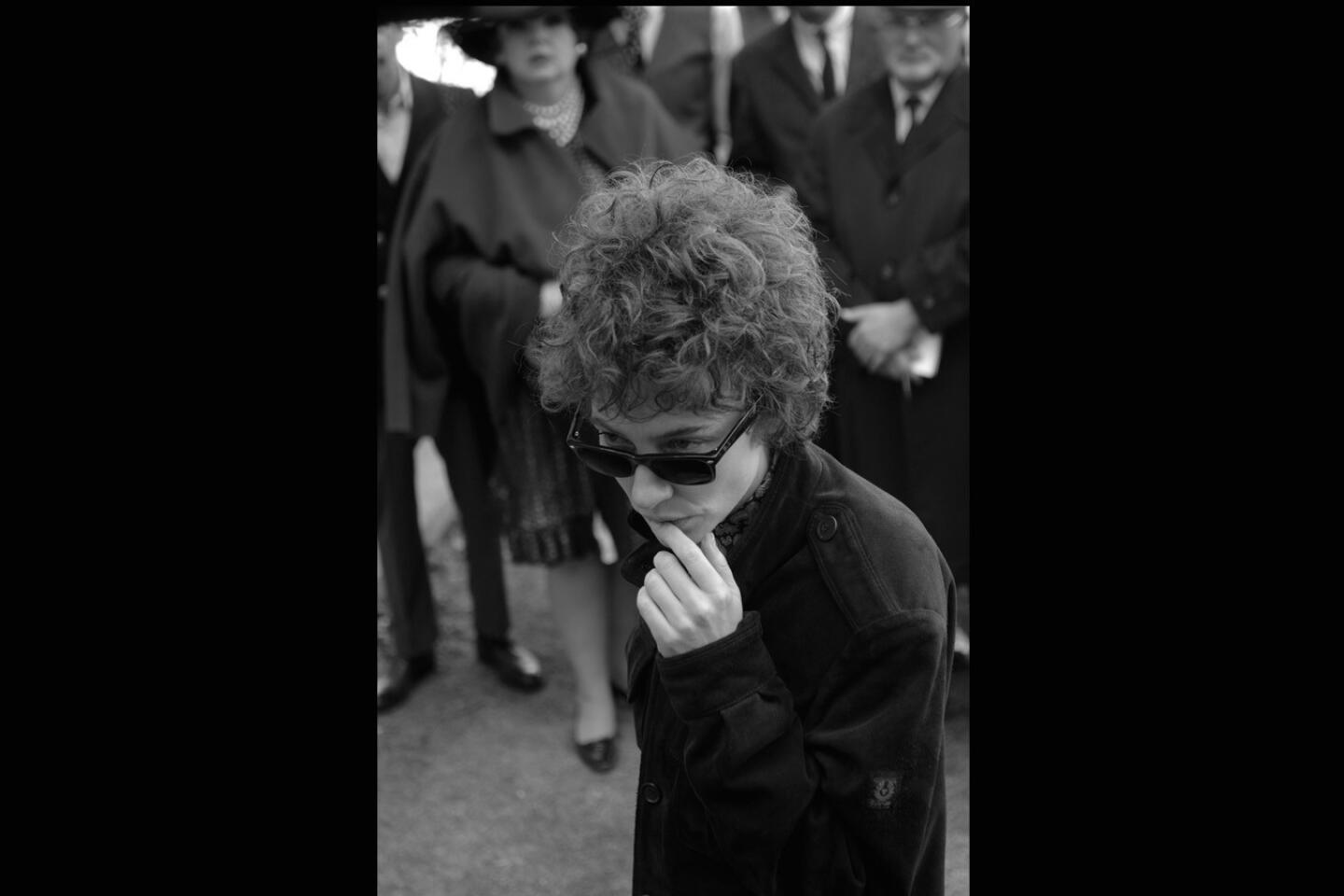

As he sits in the quiet of a grand hotel overlooking one of the city’s picturesque canals, he paints a very different picture of his evolution as a songwriter than you might expect of an artist who seemed to arrive on the pop scene in the ‘60s with his vision and skills fully intact. Dylan’s lyrics to “Blowin’ in the Wind” were printed in Broadside, the folk music magazine, in May 1962, the month he turned 21.

The story he tells is one of trial and error, false starts and hard work -- a young man in a remote stretch of Minnesota finding such freedom in the music of folk songwriter Woody Guthrie that he felt he could spend his life just singing Guthrie songs -- until he discovered his true calling through a simple twist of fate.

Dylan has often said that he never set out to change pop songwriting or society, but it’s clear he was filled with the high purpose of living up to the ideals he saw in Guthrie’s work. Unlike rock stars before him, his chief goal wasn’t just making the charts.

“I always admired true artists who were dedicated, so I learned from them,” Dylan says, rocking slowly in the hotel room chair. “Popular culture usually comes to an end very quickly. It gets thrown into the grave. I wanted to do something that stood alongside Rembrandt’s paintings.”

Popular culture usually comes to an end very quickly. It gets thrown into the grave. I wanted to do something that stood alongside Rembrandt’s paintings.

— Bob Dylan

Even after all these years, his eyes still light up at the mention of Guthrie, the “Dust Bowl” poet, whose best songs, such as “This Land Is Your Land,” spoke so eloquently about the gulf Guthrie saw between America’s ideals and its practices.

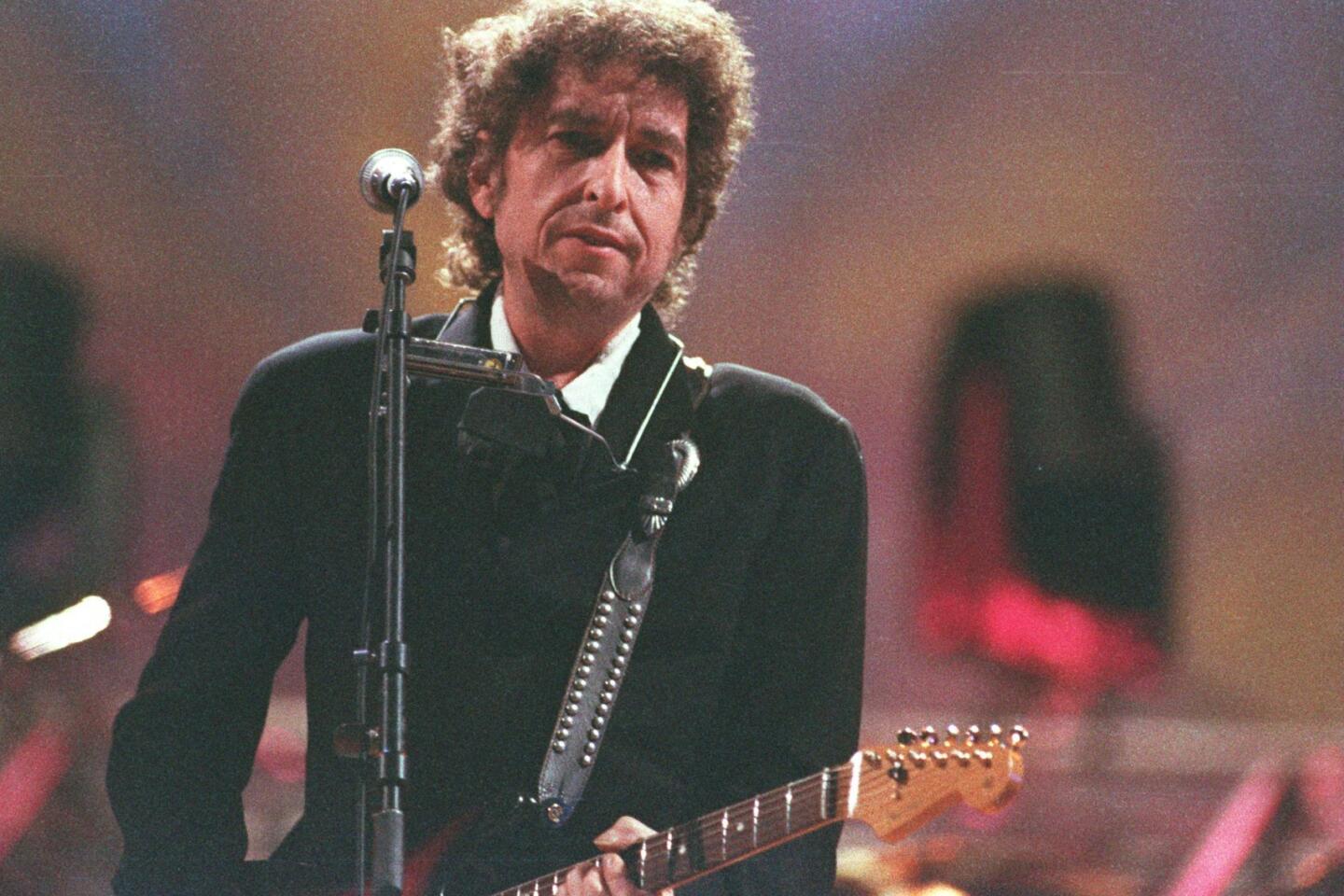

“To me, Woody Guthrie was the be-all and end-all,” says Dylan, 62, his curly hair still framing his head majestically as it did on album covers four decades ago. “Woody’s songs were about everything at the same time. They were about rich and poor, black and white, the highs and lows of life, the contradictions between what they were teaching in school and what was really happening. He was saying everything in his songs that I felt but didn’t know how to.

“It wasn’t only the songs, though. It was his voice -- it was like a stiletto -- and his diction. I had never heard anybody sing like that. His guitar strumming was more intricate than it sounded. All I knew was I wanted to learn his songs.”

Dylan played so much Guthrie during his early club and coffeehouse days that he was dubbed a Woody Guthrie “jukebox.” So imagine the shock when someone told him another singer -- Ramblin’ Jack Elliott -- was doing that too. “It’s like being a doctor who has spent all these years discovering penicillin and suddenly [finding out] someone else had already done it,” he recalls.

A less ambitious young man might have figured no big deal -- there’s plenty of room for two singers who admire Guthrie. But Dylan was too independent. “I knew I had something that Jack didn’t have,” he says, “though it took a while before I figured out what it was.”

Songwriting, he finally realized, was what could set him apart. Dylan had toyed with the idea earlier, but he felt he didn’t have enough vocabulary or life experience.

Scrambling to distinguish himself on the New York club scene in 1961, though, he tried again. The first song of his own that drew attention to him was “Song to Woody,” which included the lines, “Hey, hey, Woody Guthrie ... I know that you know / All the things that I’m a-sayin’ an’ a-many times more.”

Within two years, he had written and recorded songs, including “Girl of the North Country” and “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” that helped lift the heart of pop music from sheer entertainment to art.

‘Songs Are the Star’

Dylan, whose work and personal life have been dissected in enough books to fill a library wall, seems to welcome the chance to talk about his craft, not his persona or history. It’s as if he wants to demystify himself.

“To me, the performer is here and gone,” he once said. “The songs are the star of the show, not me.”

He also hates focusing on the past. “I’m always trying to stay right square in the moment. I don’t want to get nostalgic or narcissistic as a writer or a person. I think successful people don’t dwell in the past. I think only losers do.”

Yet his sense of tradition is strong. He likes to think of himself as part of a brotherhood of writers whose roots are in the raw country, blues and folk strains of Guthrie, the Carter Family, Robert Johnson and scores of Scottish and English balladeers.

Over the course of the evening, he offers glimpses into how his ear and eye put pieces of songs together using everything from Beat poetry and the daily news to lessons picked up from contemporaries.

He is so committed to talking about his craft that he has a guitar at his side in case he wants to demonstrate a point. When his road manager knocks on the door after 90 minutes to see if everything is OK, Dylan waves him off. After three hours, he volunteers to get together again after the next night’s concert.

“There are so many ways you can go at something in a song,” he says. “One thing is to give life to inanimate objects. Johnny Cash is good at that. He’s got the line that goes, ‘A freighter said, “She’s been here, but she’s gone, boy, she’s gone.” ’ That’s great. ‘A freighter says ‘ “She’s been here.” ’ That’s high art. If you do that once in a song, you usually turn it on its head right then and there.”

The process he describes is more workaday than capturing lightning in a bottle. In working on “Like a Rolling Stone,” he says, “I’m not thinking about what I want to say, I’m just thinking ‘Is this OK for the meter?’ ”

But there’s an undeniable element of mystery too. “It’s like a ghost is writing a song like that. It gives you the song and it goes away, it goes away. You don’t know what it means. Except the ghost picked me to write the song.”

Some listeners over the years have complained that Dylan’s songs are too ambiguous -- that they seem to be simply an exercise in narcissistic wordplay. But most critics say Dylan’s sometimes competing images are his greatest strength.

Few in American pop have consistently written lines as hauntingly beautiful and richly challenging as his “Just Like a Woman,” a song from the mid-’60s:

*

Nobody feels any pain

Tonight as I stand inside

the rain

Ev’rybody knows

That Baby’s got new clothes

But lately I see her ribbons and her bows

Have fallen from her curls.

She takes just like a woman, yes, she does

She makes love just like a woman, yes, she does

And she aches just like a woman

But she breaks just like

a little girl.

Dylan stares impassively at a lyric sheet for “Just Like a Woman” when it is handed to him. As is true of so many of his works, the song seems to be about many things at once.

“I’m not good at defining things,” he says. “Even if I could tell you what the song was about I wouldn’t. It’s up to the listener to figure out what it means to him.”

As he stares at the page in the quiet of the room, however, he budges a little. “This is a very broad song. A line like, ‘Breaks just like a little girl’ is a metaphor. It’s like a lot of blues-based songs. Someone may be talking about a woman, but they’re not really talking about a woman at all. You can say a lot if you use metaphors.”

After another pause, he adds: “It’s a city song. It’s like looking at something extremely powerful, say the shadow of a church or something like that. I don’t think in lateral [sic] terms as a writer. That’s a fault of a lot of the old Broadway writers.... They are so lateral. There’s no circular thing, nothing to be learned from the song, nothing to inspire you. I always try to turn a song on its head. Otherwise, I figure I’m wasting the listener’s time.”

Discovering Folk Music

Dylan’s pop sensibilities were shaped long before he made his journey east in the winter of 1960-61.

Growing up in the icy isolation of Hibbing, Minn., Dylan, who was still Robert Allen Zimmerman then, found comfort in the country, blues and early rock ‘n’ roll that he heard at night on a Louisiana radio station whose signal came in strong and clear. It was worlds away from the local Hibbing station, which leaned toward mainstream pop like Perry Como, Frankie Laine and Doris Day.

Dylan has respect for many of the pre-rock songwriters, citing Cole Porter, whom he describes as a “fearless” rhymer, and Porter’s “Don’t Fence Me In” as a favorite. But he didn’t feel most of the pre-rock writers were speaking to him.

“When you listened to [Porter’s] songs and the Gershwins’ and Rodgers and Hammerstein, who wrote some great songs, they were writing for their generation and it just didn’t feel like mine,” he says. “I realized at some point that the important thing isn’t just how you write songs, but your subject matter, your point of view.”

The music that did speak to him as a teenager in the ‘50s was rock ‘n’ roll -- especially Elvis Presley. “When I got into rock ‘n’ roll, I didn’t even think I had any other option or alternative,” he says. “It showed me where my future was, just like some people know they are going to be doctors or lawyers or shortstop for the New York Yankees.”

He became a student of what he heard.

“Chuck Berry wrote amazing songs that spun words together in a remarkably complex way,” he says. “Buddy Holly’s songs were much more simplified, but what I got out of Buddy was that you can take influences from anywhere. Like his ‘That’ll Be the Day.’ I read somewhere that it was a line he heard in a movie, and I started realizing you can take things from everyday life that you hear people say.

“That I still find true. You can go anywhere in daily life and have your ears open and hear something, either something someone says to you or something you hear across the room. If it has resonance, you can use it in a song.”

After rock took on a blander tone in the late ‘50s, Dylan looked for new inspiration. He began listening to the Kingston Trio, who helped popularize folk music with polished versions of “Tom Dooley” and “A Worried Man.” Most folk purists felt the group was more “pop” than authentic, but Dylan, new to folk, responded to the messages in the songs.

He worked his way through such other folk heroes as Odetta and Leadbelly before fixating on Guthrie. Trading his electric guitar for an acoustic one, he spent months in Minneapolis, performing in clubs, preparing himself for the trip east.

Going to New York rather than rival music center Los Angeles was a given, he says, “because everything I knew came out of New York. I listened to the Yankees games on the radio, and the Giants and the Dodgers. All the radio programs, like ‘The Fat Man,’ the NBC chimes -- would be from New York. So were all the record companies. It seemed like New York was the capital of the world.”

Devouring Poetry

Dylan pursued his muse in New York with an appetite for anything he felt would help him improve his craft, whether it was learning old blues and folk songs or soaking up literature.

“I had read a lot of poetry by the time I wrote a lot of those early songs,” he volunteers. “I was into the hard-core poets. I read them the way some people read Stephen King. I had also seen a lot of it growing up. Poe’s stuff knocked me out in more ways than I could name. Byron and Keats and all those guys. John Donne.

“Byron’s stuff goes on and on and on and you don’t know half the things he’s talking about or half the people he’s addressing. But you could appreciate the language.”

He found himself side by side with the Beat poets. “The idea that poetry was spoken in the streets and spoken publicly, you couldn’t help but be excited by that,” he says. “There would always be a poet in the clubs and you’d hear the rhymes, and [Allen] Ginsberg and [Gregory] Corso -- those guys were highly influential.”

Dylan once said he wrote songs so fast in the ‘60s that he didn’t want to go to sleep at night because he was afraid he might miss one. Similarly, he soaked up influences so rapidly that it was hard to turn off the light at night. Why not read more?

“Someone gave me a book of Francois Villon poems and he was writing about hard-core street stuff and making it rhyme,” Dylan says, still conveying the excitement of tapping into inspiration from 15th century France. “It was pretty staggering, and it made you wonder why you couldn’t do the same thing in a song.

“I’d see Villon talking about visiting a prostitute and I would turn it around. I won’t visit a prostitute, I’ll talk about rescuing a prostitute. Again, it’s turning stuff on its head, like ‘vice is salvation and virtue will lead to ruin.’ ”

When you hear Dylan still marveling at lines such as the one above from Machiavelli or Shakespeare’s “fair is foul and foul is fair,” you can see why he would pepper his own songs with phrases that forever ask us to question our assumptions -- classic lines such as “There’s no success like failure and failure’s no success at all,” from 1965’s “Love Minus Zero/No Limit.”

As always, he’s quick to give credit to the tradition.

“I didn’t invent this, you know,” he stresses. “Robert Johnson would sing some song and out of nowhere there would be some kind of Confucius saying that would make you go, ‘Wow, where did that come from?’ It’s important to always turn things around in some fashion.”

Exploring his themes

Some writers sit down every day for two or three hours, at least, to write, whether they are in the mood or not. Others wait for inspiration. Dylan scoffs at the discipline of daily writing.

“Oh, I’m not that serious a songwriter,” he says, a smile on his lips. “Songs don’t just come to me. They’ll usually brew for a while, and you’ll learn that it’s important to keep the pieces until they are completely formed and glued together.”

He sometimes writes on a typewriter but usually picks up a pen because he says he can write faster than he can type. “I don’t spend a lot of time going over songs,” Dylan says. “I’ll sometimes make changes, but the early songs, for instance, were mostly all first drafts.”

He doesn’t insist that his rhymes be perfect. “What I do that a lot of other writers don’t do is take a concept and line I really want to get into a song and if I can’t figure out for the life of me how to simplify it, I’ll just take it all -- lock, stock and barrel -- and figure out how to sing it so it fits the rhyming scheme. I would prefer to do that rather than bust it down or lose it because I can’t rhyme it.”

Themes, he says, have never been a problem. When he started out, the Korean War had just ended. “That was a heavy cloud over everyone’s head,” he says. “The communist thing was still big, and the civil rights movement was coming on. So there was lots to write about.

“But I never set out to write politics. I didn’t want to be a political moralist. There were people who just did that. Phil Ochs focused on political things, but there are many sides to us, and I wanted to follow them all. We can feel very generous one day and very selfish the next hour.”

Dylan found subject matter in newspapers. He points to 1964’s “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,” the story of a wealthy Baltimore man who was given only a six-month sentence for killing a maid with a cane. “I just let the story tell itself in that song,” he says. “Who wouldn’t be offended by some guy beating an old woman to death and just getting a slap on the wrist?”

Other times, he was reacting to his own anxieties.

“A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” helped define his place in pop with an apocalyptic tale of a society being torn apart on many levels.

*

I heard the sound of a thunder, it roared out a warnin’

Heard the roar of a wave that could drown the whole world.

Heard one hundred drummers whose hands were a-blazin’

Heard ten thousand whisperin’ and nobody listenin’ ...

And it’s a hard rain’s a-gonna fall.

The song has captured the imagination of listeners for generations, and like most of Dylan’s songs, it has lyrics rich and poetic enough to defy age. Dylan scholars have often said the song was inspired by the Cuban missile crisis.

“All I remember about the missile crisis is there were bulletins coming across on the radio, people listening in bars and cafes, and the scariest thing was that cities, like Houston and Atlanta, would have to be evacuated. That was pretty heavy.

“Someone pointed out it was written before the missile crisis, but it doesn’t really matter where a song comes from. It just matters where it takes you.”

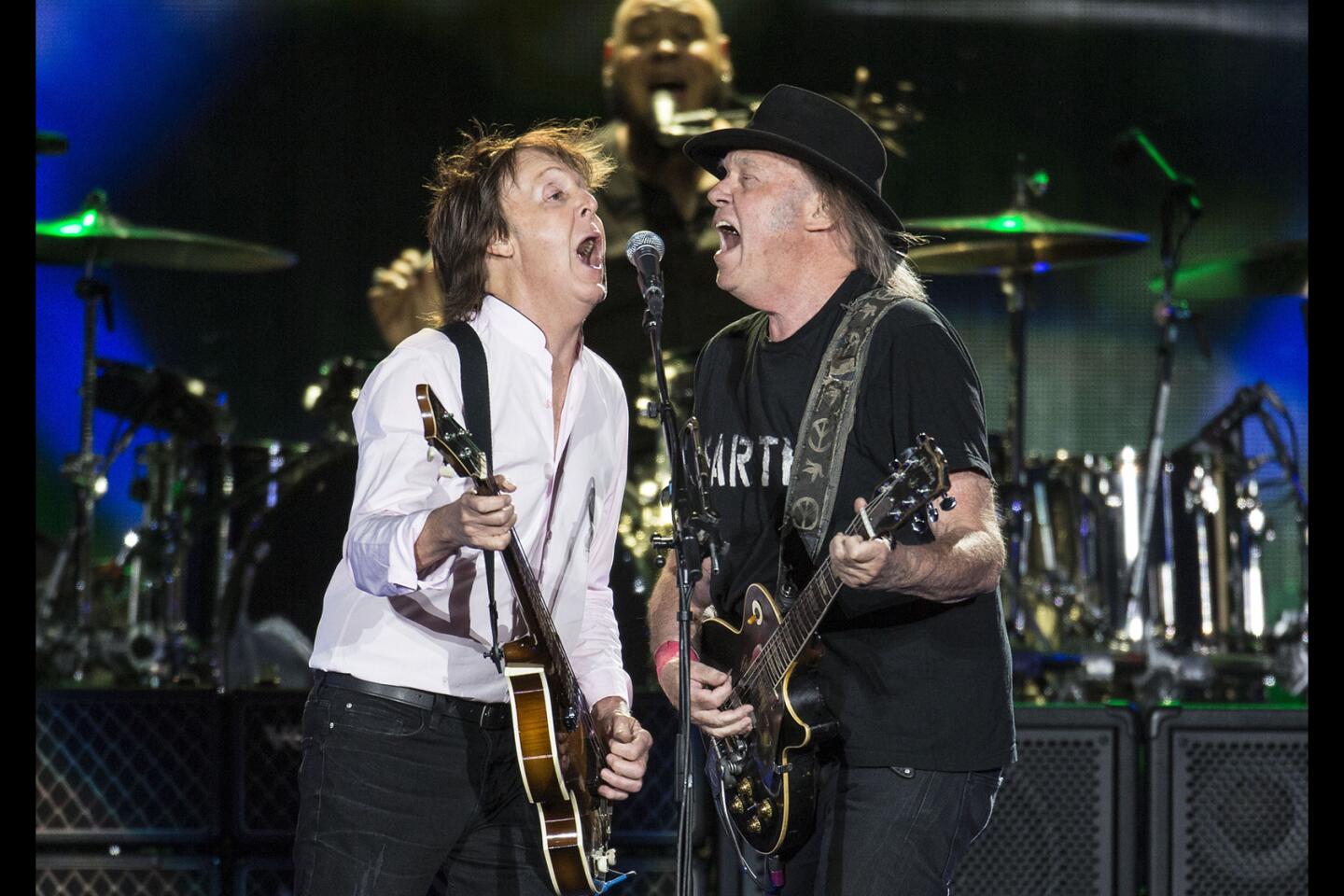

From the Beatles to the Beach Boys to Bob Dylan, The Times’ Randy Lewis explores some of the landmark albums from rock’s most explosive year -- 1966.

His Constant Changes

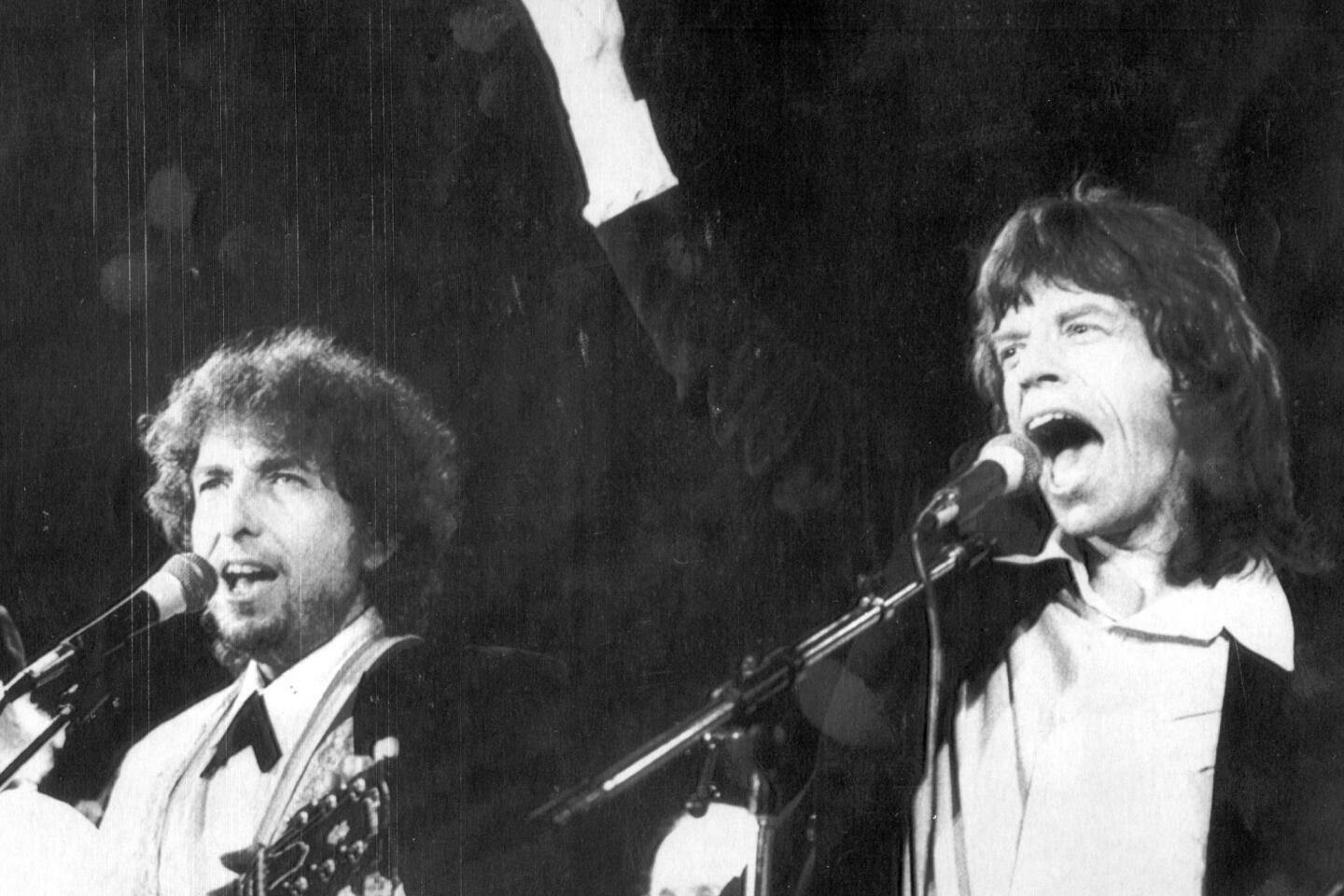

Dylan’s career path hasn’t been smooth. During an unprecedented creative spree that resulted in three landmark albums (“Bringing It All Back Home,” “Highway 61 Revisited” and “Blonde on Blonde”) being released in 15 months, Dylan reconnected with the rock ‘n’ roll of his youth. Impressed by the energy he felt in the Beatles and desiring to speak in the musical language of his generation, he declared his independence from folk by going electric at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965.

His music soon became a new standard of rock achievement, influencing not only his contemporaries, including the Beatles, but almost everyone to follow.

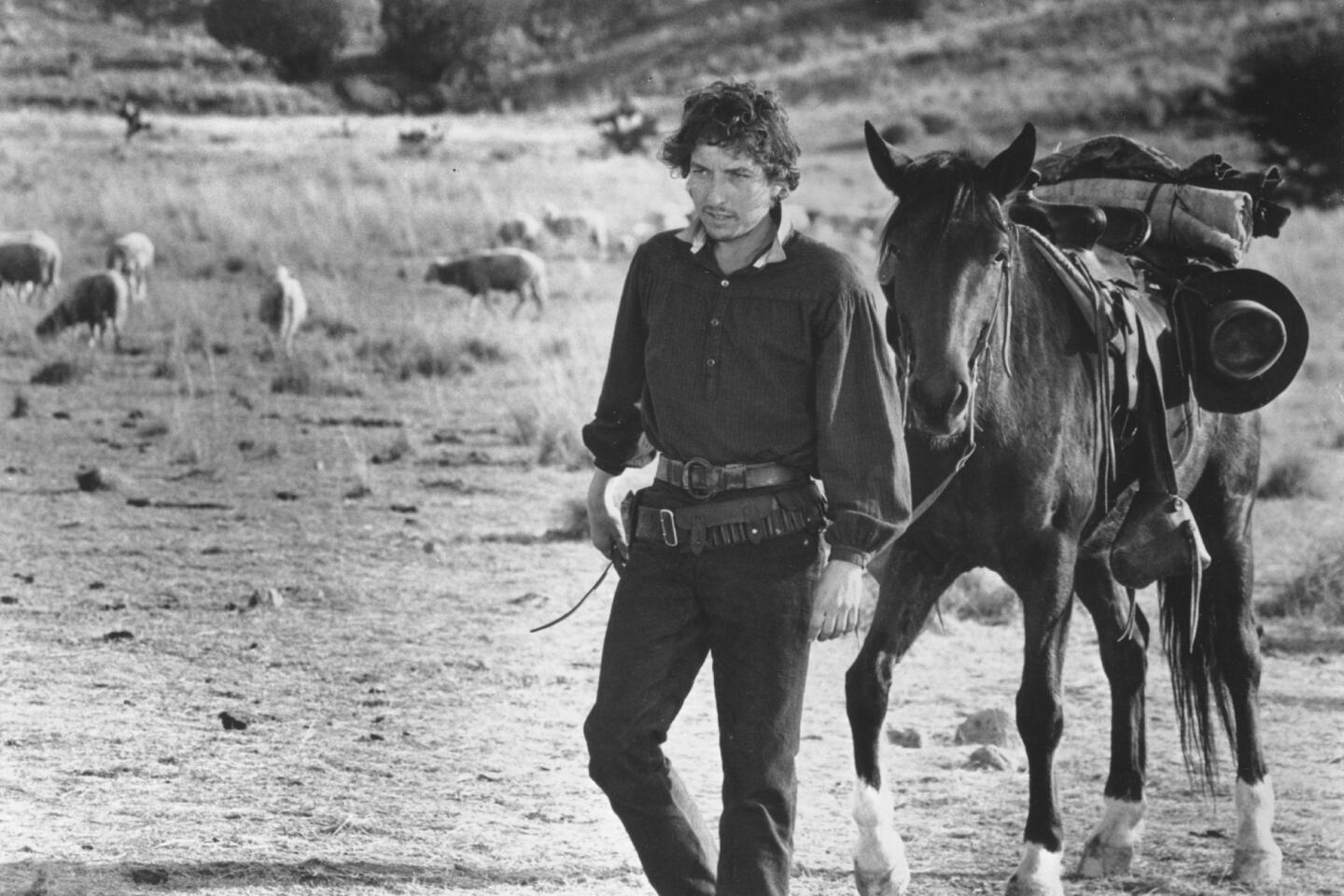

The pressure on him was soon so intense that he went underground for a while in 1966, not fully resuming his career until the mid-’70s when he did a celebrated tour with the Band and then recorded one of his most hailed albums, “Blood on the Tracks.” By the end of the decade, he confused some old fans by turning to brimstone gospel music.

There were gems throughout the ‘70s and ‘80s, but Dylan seemed for much of the ‘90s to be tired of songwriting, or, maybe, just tired of always being measured against the standards he set in the ‘60s.

In the early ‘90s he seemed to find comfort only in the rhythm of the road, losing himself in the troubadour tradition, not even wanting to talk about songwriting or his future. “Maybe I’ve written enough songs,” he said then. “Maybe it’s someone else’s turn.”

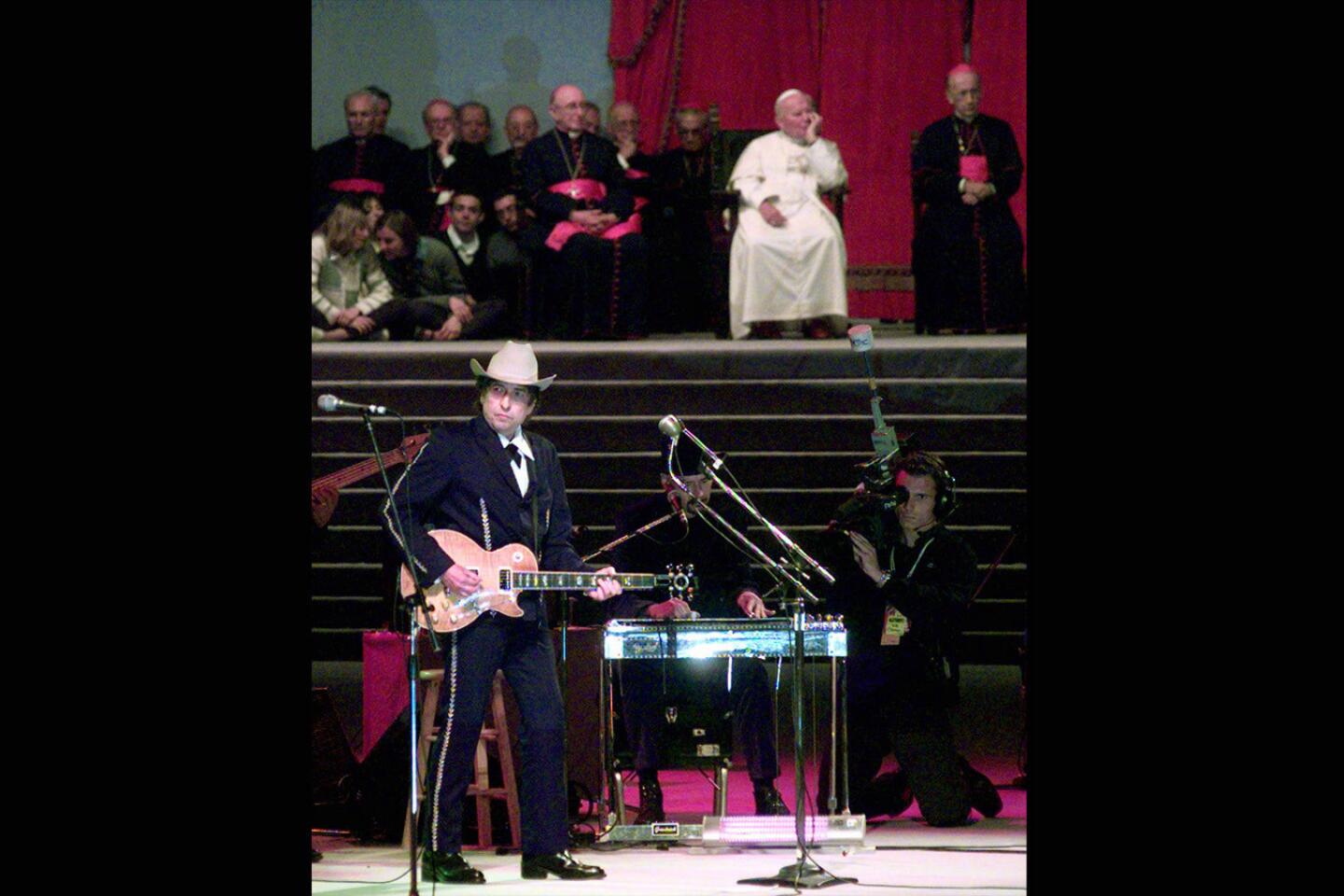

Somehow, however, all those shows reignited the songwriting spark -- as demonstrated in his Grammy-winning “Time Out of Mind” album in 1997; the bittersweet song from the movie “Wonder Boys,” “Things Have Changed,” that won an Oscar in 2001 for best original song; and his heralded 2001 album, “Love and Theft.” He spent much of last year working on a series of autobiographical chronicles. The first installment is due this fall from Simon & Schuster.

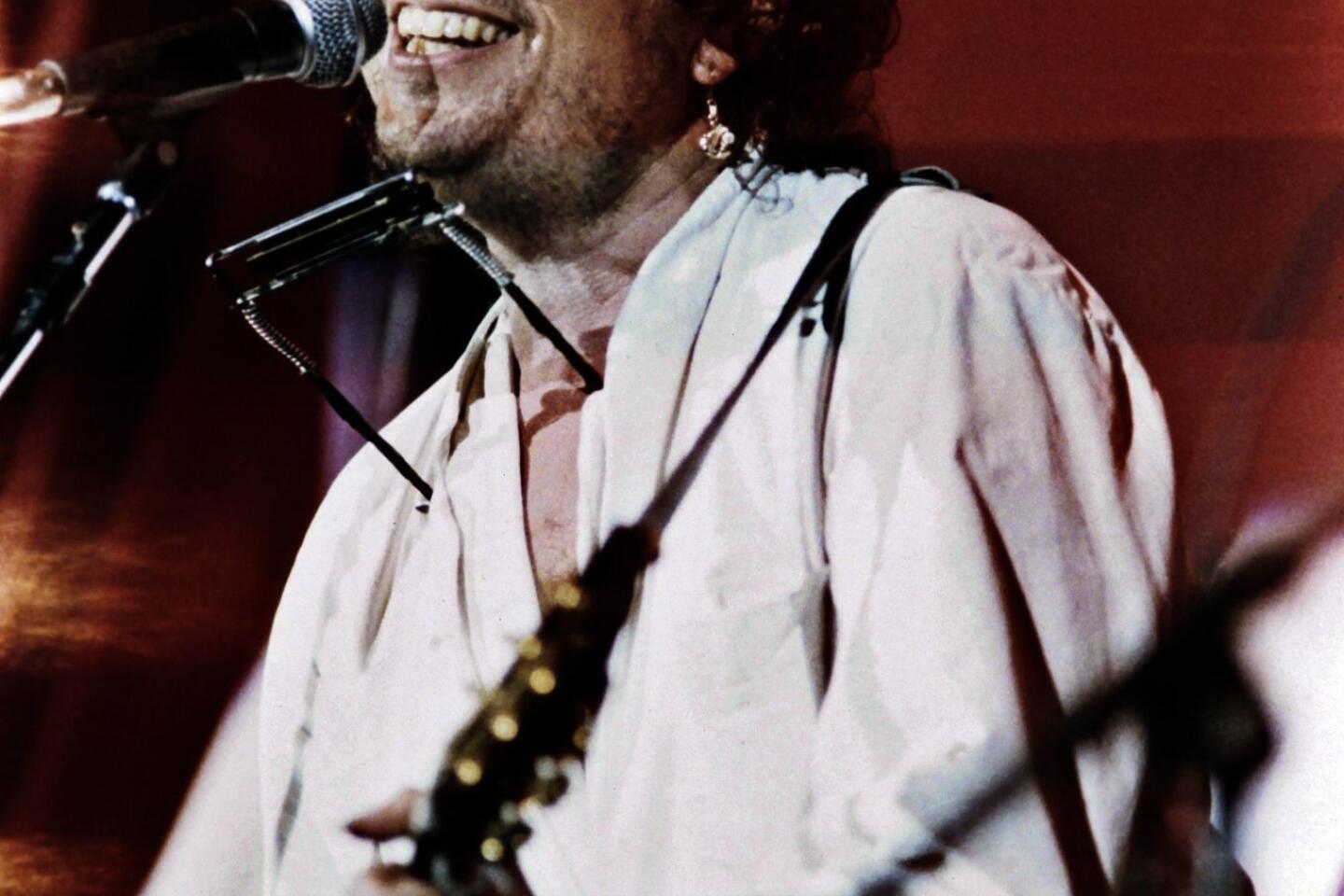

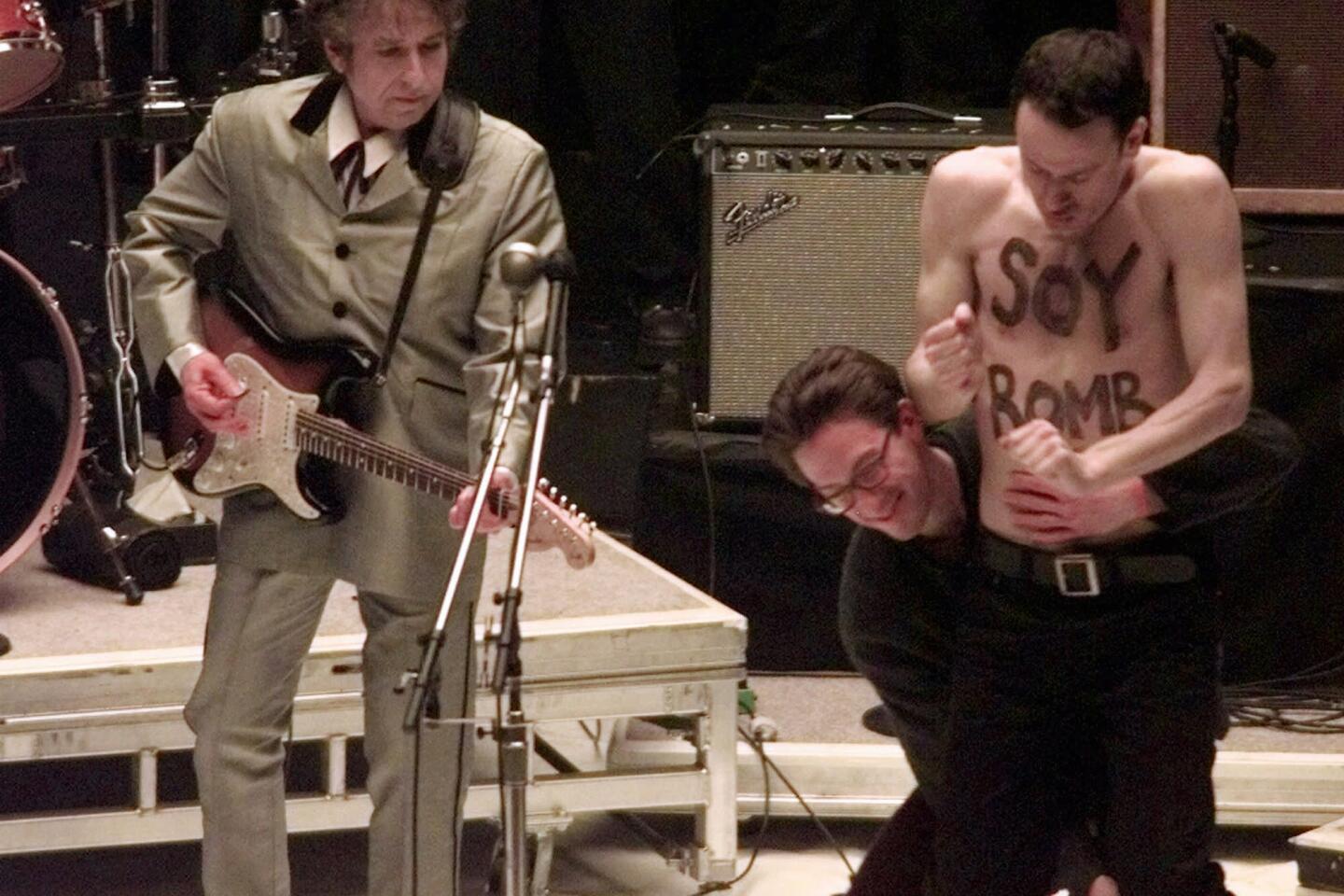

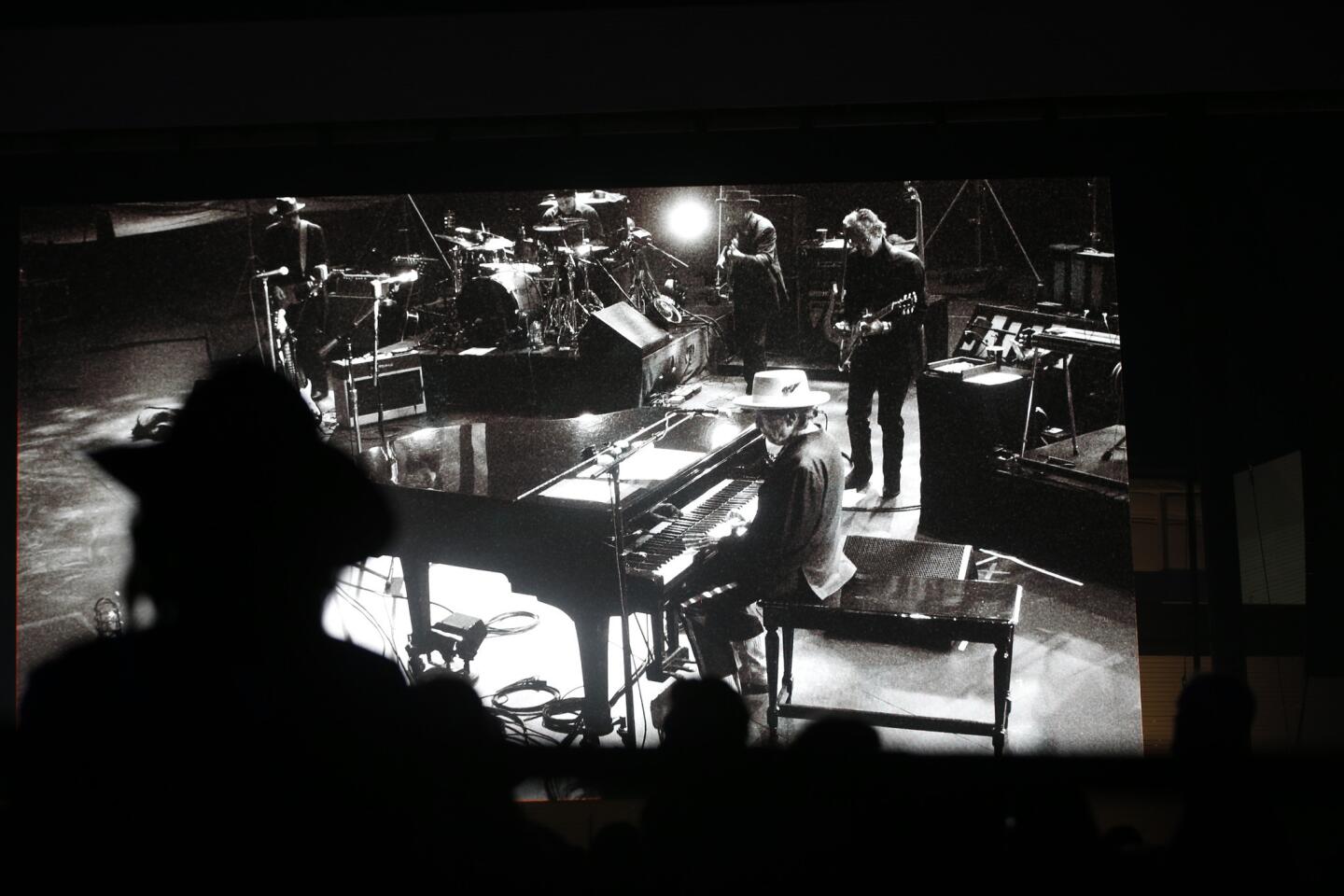

But nowhere, perhaps, is Dylan’s regained passion more evident than in his live show, where he has switched primarily from guitar to electric keyboard and now leads his four-piece band with the intensity of a young punk auteur.

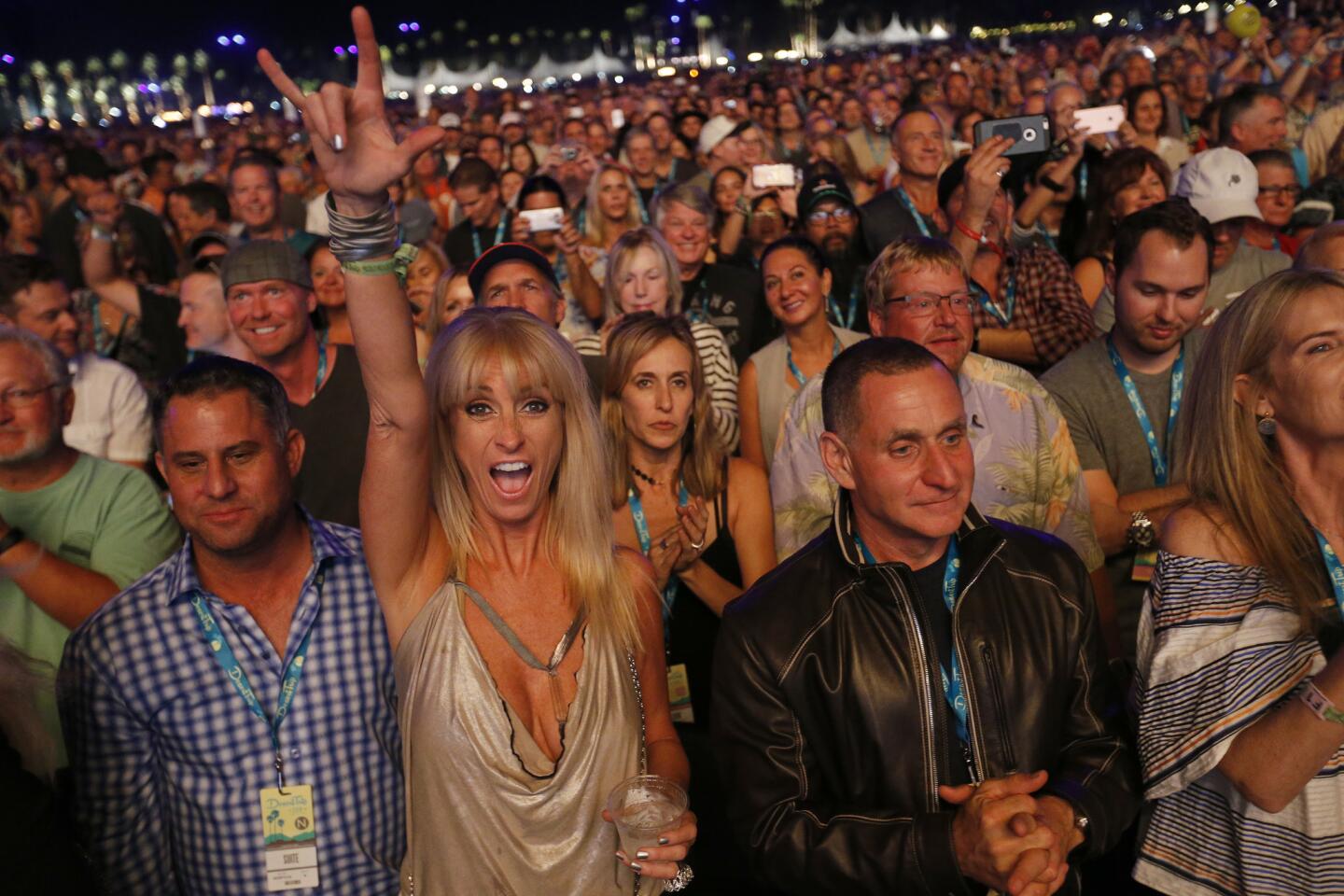

Dylan -- who has lived in Southern California since he and ex-wife Sara Lowndes moved to Malibu in the mid-’70s with their five children -- was in Amsterdam to headline two sold-out concerts at a 6,000-seat hall. He does more than 100 shows a year.

The audience on the chilly winter night after our first conversation is divided among people Dylan’s age who have been following his career since the ‘60s and young people drawn to him by his classic body of work, and they call out for new songs, not just the classics.

Refiguring the Melodies

Back at the hotel afterward, Dylan looks about as satisfied as a man with his restless creative spirit can be.

It’s nearly 2 a.m. by now and another pot of coffee cools. He rubs his hand through his curly hair. After all these hours, I realize I haven’t asked the most obvious question: Which comes first, the words or the music?

Dylan leans over and picks up the acoustic guitar.

“Well, you have to understand that I’m not a melodist,” he says. “My songs are either based on old Protestant hymns or Carter Family songs or variations of the blues form.

“What happens is, I’ll take a song I know and simply start playing it in my head. That’s the way I meditate. A lot of people will look at a crack on the wall and meditate, or count sheep or angels or money or something, and it’s a proven fact that it’ll help them relax. I don’t meditate on any of that stuff. I meditate on a song.

“I’ll be playing Bob Nolan’s ‘Tumbling Tumbleweeds,’ for instance, in my head constantly -- while I’m driving a car or talking to a person or sitting around or whatever. People will think they are talking to me and I’m talking back, but I’m not. I’m listening to the song in my head. At a certain point, some of the words will change and I’ll start writing a song.”

He’s slowly strumming the guitar, but it’s hard to pick out the tune.

“I wrote ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’ in 10 minutes, just put words to an old spiritual, probably something I learned from Carter Family records. That’s the folk music tradition. You use what’s been handed down. ‘The Times They Are A-Changin’ is probably from an old Scottish folk song.”

As he keeps playing, the song starts sounding vaguely familiar.

I want to know about “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” one of his most radical songs. The 1965 number fused folk and blues in a way that made everyone who heard it listen to it over and over. John Lennon once said the song was so captivating on every level that it made him wonder how he could ever compete with it.

The lyrics, again, were about a society in revolution, a tale of drugs and misuse of authority and trying to figure out everything when little seemed to make sense:

*

Johnny’s in the basement

Mixing up the medicine

I’m on the pavement

Thinking about the government

*

The music too reflected the paranoia of the time -- roaring out of the speakers at the time with a cannonball force.

Where did that come from?

Without pause, Dylan says, almost with a wink, that the inspiration dates to his teens. “It’s from Chuck Berry, a bit of ‘Too Much Monkey Business’ and some of the scat songs of the ‘40s.”

As the music from the guitar gets louder, you realize Dylan is playing one of the most famous songs of the 20th century, Irving Berlin’s “Blue Skies.”

You look into his eyes for a sign.

Is he writing a new song as we speak?

“No,” he says with a smile. “I’m just showing you what I do.”

Five songs for the ages

You could make a dozen lists of your five favorite Dylan songs and still be satisfied with the tunes on the 12th list. But here are the songs, in order, that I’d put on my first list of five.

1. “Like a Rolling Stone” 1965. Dylan says he never meant to be a spokesman, but he sure seems to have captured the restless feel of an age in this anthem. The unforgettable chorus: “How does it feel? / To be on your own / With no direction home / Like a complete unknown / Like a rolling stone?”

2. “Love Minus Zero/No Limit” 1965. The greatness of Dylan’s art is in its ability to move from the social arena to the personal one without losing intensity. Here’s a tale of the heart, told with a sense of poetry and passion that is at once eloquent and forever mysterious. Its haunting opening lines: “My love she speaks like silence / Without ideals or violence / She doesn’t have to say she’s faithful / Yet she’s true, like ice, like fire.”

3. “To Ramona” 1964. This is among the most beautiful and mysterious love songs ever written. The imagery is inspired: “Ramona, come closer / Shut softly your watery eyes / The pangs of your sadness / Shall pass as your senses will rise.”

4. “It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” 1965. There are lots of early Dylan songs, including “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” that mix commentary and music with such unerring force that you could imagine even Woody Guthrie being impressed, but none more than this one. A breathless sense of ambition.

5. “I Believe in You” 1979. This spiritual-tinged tune from the “Slow Train Coming” album may be Dylan’s most intimate expression of faith and, at the same time, a glimpse at the price an artist pays for following his own heart. “They’d like to drive me from this town / They don’t want me around / ‘Cause I believe in you.”

ALSO:

Bob Dylan, interpreter: Seven of the artist’s greatest covers

In a ‘radical’ choice, Bob Dylan wins the Nobel Prize in literature

Online, some wonder if Bob Dylan really needs a Nobel Prize

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.