‘La La Land’s’ Damien Chazelle and ‘Spotlight’s’ Josh Singer return to the Oscar race with ‘First Man’

- Share via

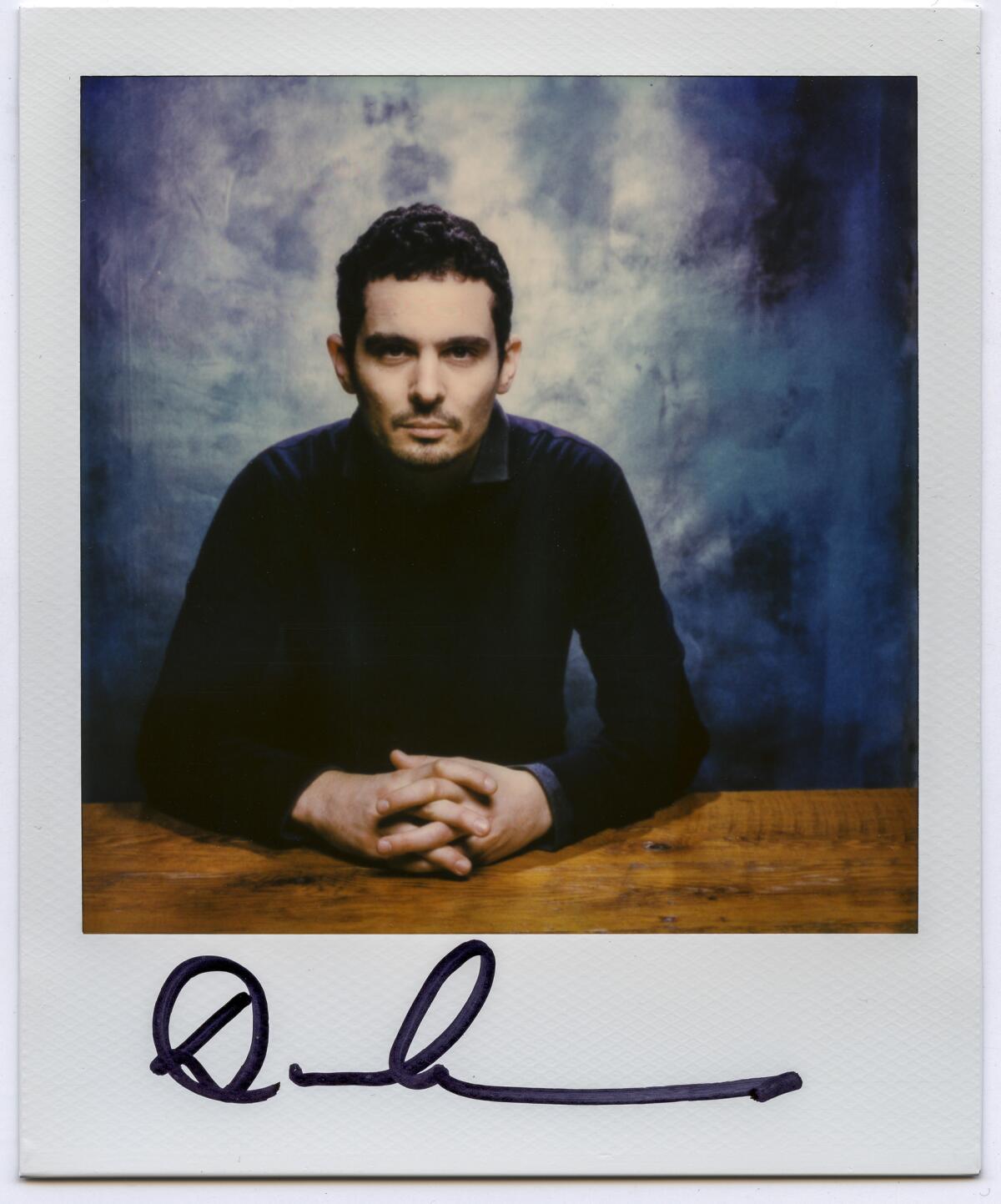

Reporting from Telluride, Colo. — Damien Chazelle just made a movie about the greatest triumph in the history of space exploration: “First Man,” about astronaut Neil Armstrong’s journey to become the first man to set foot on the moon. But don’t expect to see him signing up with Elon Musk for a ride into the cosmos anytime soon.

“This movie was very much shot and told from the perspective of nervous fliers,” Chazelle said with a laugh, sitting beside the film’s screenwriter, Josh Singer, the day after its first screening at the Telluride Film Festival. “Space travel has not been something I’ve craved doing, and this movie in many ways is why I’m not actually personally wanting to go into space.”

Judging by the reactions to the film both at the Venice Film Festival and Telluride, though, “First Man” seems likely to send the 33-year-old Chazelle — who broke out with 2014’s “Whiplash” and became the youngest person to win the best director Oscar for the 2016 musical “La La Land” — back into awards-season orbit.

Early reviews have praised “First Man” — which stars Gosling as Armstrong and Claire Foy as his wife Janet and hits theaters Oct. 12 — as a viscerally and emotionally gripping account of Armstrong’s story, even as some controversy has erupted over Chazelle’s decision not to dramatize the moment when Armstrong planted the American flag on the moon. (For the record, there are multiple shots of the American flag next to the Apollo 11 lunar lander, as well as at various other points in the movie.)

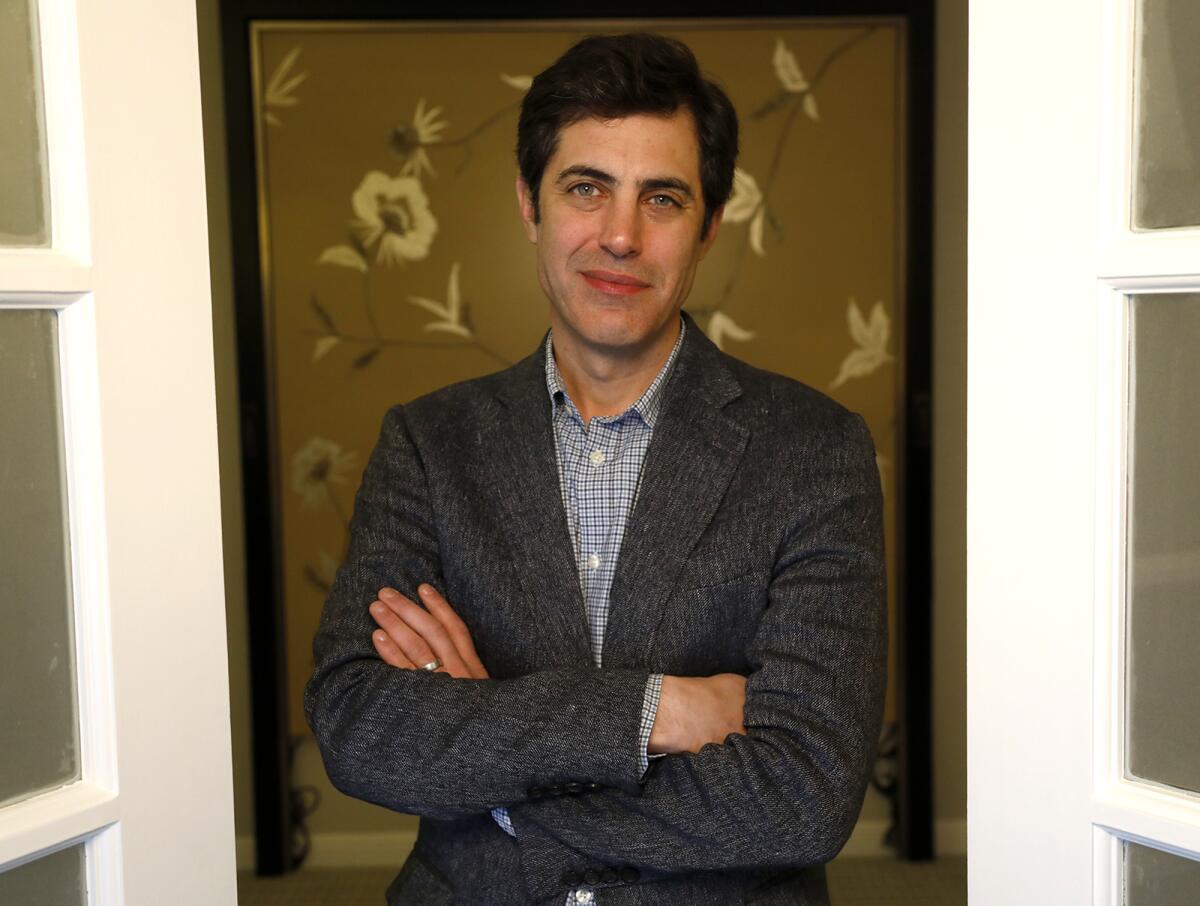

The Times spoke with Chazelle and Singer, who won the original screenplay Oscar with Tom McCarthy for “Spotlight,” about finding Armstrong as a character, the flag flap and balancing artistic and commercial ambitions in this sweeping space odyssey.

“Whiplash,” “La La Land” and “First Man” are all incredibly different movies but on one level they’re all about people pursuing a difficult dream and what they have to sacrifice along the way. Damien, is that a conscious thread for you?

Chazelle: I think that’s what got me into the idea for this movie. Because I didn’t grow up as a space nut. I didn’t grow up wanting to tell a Neil Armstrong story per se. It was starting to think about it and looking at the archival materials and realizing, “Oh, this myth, this story that seems so gleamingly successful that it’s almost sort of bland — there’s actually a tortuous journey to that success story that was beset by failure and loss and tragedy.”

Suddenly then it felt like another variation on that theme of what the price of pursuing a goal like that is on the individual, on the people around them — and with a mission like this, certainly what the price was on the whole nation that shouldered it.

Singer: The idea of puncturing the myth and getting at the human cost — I mean, Neil was one of nine guys in the second group of astronauts, and two of them died and those two happened to be his closest friends in the program. There was incredible loss and sacrifice here.

These guys were not supermen. They were just ordinary men and women doing their best and sacrificing greatly in order to achieve something for all of us. And in an era right now when we face impossible tasks — like how are we going to take on climate change and save our species — I think this sugar-coating that’s been done does a disservice. There’s no hero coming to save us. We have to all step up and sacrifice the way these guys did. I think that’s inspiring.

In a lot of popular culture, like the movie “The Right Stuff,” the early astronauts have been portrayed as kind of macho space cowboys. The Neil Armstrong we see in this movie is not that at all — he’s a serious engineer who’s emotionally very self-contained.

Chazelle: I think the New Nine group of astronauts were less of the space cowboy types than the original [Mercury] 7, which was “The Right Stuff” — and within the New 9, Neil was by far the least space cowboy of that group. To me, that makes him both more relatable and harder to fathom. Because it’s one thing to look at the kind of hotshot pilot who brags about cheating death, that adrenaline-junkie type, as a character. It’s another to look at someone like Neil.

My dad is a mathematician and aspects of him remind me of Neil: just someone who liked to sit in his attic and work on math problems and live in his head all day long. For someone like that to then be willing and even desiring to put themselves in totally death-defying situations, it made it both more interesting to me and harder to figure out.

The fact that he was so self-contained, that he was so private, I think that made him very poignant as a hero. There’s this fundamental mystery about him that I think makes him endlessly compelling.

How did you get inside his head then?

Chazelle: By the time we started working on the movie, Neil had died a few years prior, so I think the biggest thing for us was just leaning as much as we could into everyone who knew him well from different aspects of his life.

His sons were incredibly helpful to us. His wife at the time, Janet, gave us a lot of her time very generously. Jim Hansen, his biographer, had all his original notes from his conversations with Armstrong. I went to Ohio with Ryan to visit the farm where Neil grew up and sit with his sister and childhood best friend. And then there were people like Dave Scott and Mike Collins, who had flown with Armstrong, trained him, worked side by side with him. We didn’t have Neil to turn to, but we had this kind of galaxy — sorry for the pun — of people around him to lean into.

In the last couple of days, controversy has flared up over your decision not to show Armstrong planting an American flag on the moon. Were you surprised when this came up, or did you consider as you were planning out that part of the film that some people might feel that moment should be in there?

Chazelle: I mean, it surprised me because there are so many things that we weren’t able to focus on not only during the lunar EVA [extra-vehicular activity] but in the entirety of Apollo 11. Just by the nature of the story we were telling, we just couldn’t go into every detail. So our through-line became — especially at this part of the movie where it’s the final emotional journey for Neil — what were the private, unknown moments of Neil on the moon?

The flag was not a private, unknown moment for Neil. It’s a very famous moment and it wasn’t Neil alone. We included the famous descent down the ladder because that’s him alone, literally first feeling what it’s like to be on the moon. But other than that, we only wanted to focus on the unfamous stuff on the moon. So we don’t go into the phone call with Nixon, we don’t go into the scientific experiments, we don’t go into reentry, et cetera.

What was important to us was that mysterious 10 minutes that Neil spent alone at the Little West crater, the walk that he took to that crater separate from Buzz [Aldrin] — during which time, of course, we wanted to look back and see the flag standing proudly by the LEM [lunar excursion module], which we showed in several shots. Neil never really talked about what he did at that crater or what he was thinking about. And in terms of the process of being on the moon, I think we were exclusively interested in the private and the less knowable.

Singer: I think there’s something else at play, too. If you look historically, the moon mission was initially very much about the competition between the U.S. and the Soviets and it was very much born of the Cold War. But as you move through the ’60s, that competition falls away just a bit and it becomes about something else. So much changes around these astronauts — the civil rights movement, the Vietnam War — and the moon mission is no longer a top priority. In fact, most Americans actually think we’re spending too much on the moon by the time they go.

By the time they get there, it really becomes something that was “for all mankind,” which was on the plaque that they put up. They debated whether to put up a U.N. flag or an American flag. And the government was very adamant about them doing a world tour afterwards to make it feel the way it felt when they landed, which was as a victory for humankind in addition to a victory for America. So I think there are other historical aspects at play.

If nothing else, the whole flap highlights how polarized things are now and the fact that everything is being viewed through a political lens. Do you see this movie as having a political message in any way?

Chazelle: I think the focus for me and for Josh and Ryan on this was on the personal and not the political. That said, I think it’s fair to say that, whether we’re talking about today or the whole history of movies up to today, every movie, every work of art, has a political component whether it wants to or not.

To me, if there’s a political component here, it’s actually trying to, again, puncture some mythology that I think has actually in some ways done some disservice to us as people who want to learn from the past.

Growing up, I just saw this period as a string of successes. This was America at its greatest. There were superheroes that went out into space and everything went perfectly because everyone was so great. And I think — especially in a day and age when we face so many challenges — that can make you defeatist in a way because you think, “Of course, we’re not going to be able to do X, Y and Z because we don’t have ‘the stuff’ they had back then.”

These people were not superheroes. They were fallible human beings struggling to do something, working very hard at it, and mostly failing. As Neil says in the movie, “You fail down here so you don’t fail up there.” Mostly what they did down here was fail and sometimes that cost lives, it certainly cost a lot of money and it created a lot of controversy.

The more you delve into the nitty-gritty of it, the more messy and difficult that whole chapter was. And that, I think, actually makes it much more useful for today: to learn from those mistakes, learn from those successes, learn from all of it and not just think, “Well, back in the gilded days we knew how to do things and now we don’t.” That’s just not true.

This is a big-budget commercial movie that also has big artistic ambitions. Did you feel a tug-of-war between those two demands?

Chazelle: I went into it with some trepidation that that might be something we’d have to navigate, but I feel really lucky to say that it never really felt like that.

It was always about making it feel like a documentary, making it feel like a home movie that extended into the spacecrafts, and that this was going to be a dark, complicated movie. This was not going to be something that it didn’t want to be. We were very open about that from the get-go, and we were very lucky to have great producers and a studio that supported it and champions along the way that helped protect the movie. I never felt like we had to make a single creative compromise along the way to sort of please the commercial masters, so to speak.

We wanted to do something that did both. It’s still kind of the holy grail, when I think of the ’70s, when things like that weren’t mutually exclusive, where you can do something on a big scale that demands to be seen in a movie theater but that is just as intimate and maybe at times weird and personal as any arthouse film, whatever that means.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.