In his films, Prince melded music and image into something powerful

- Share via

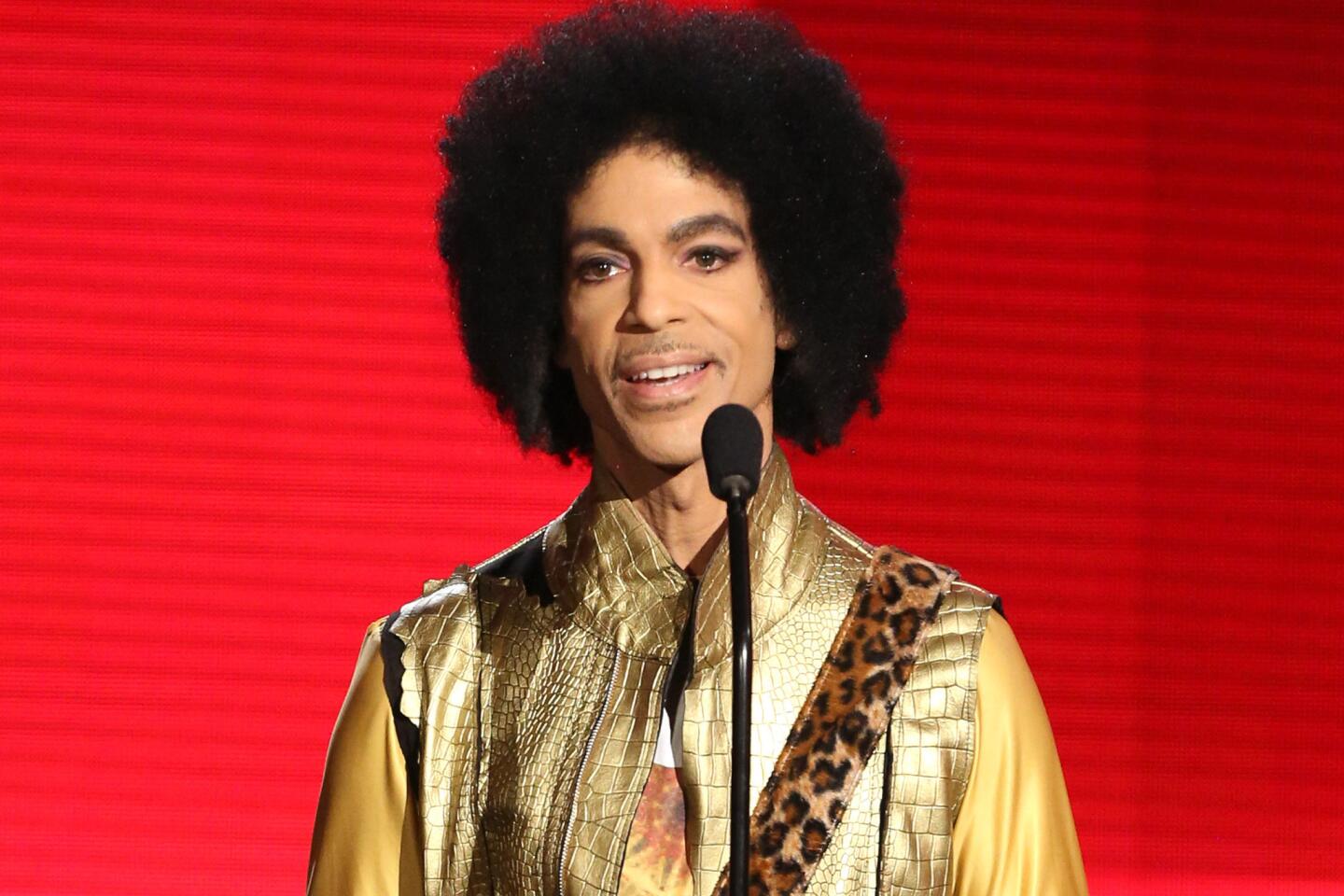

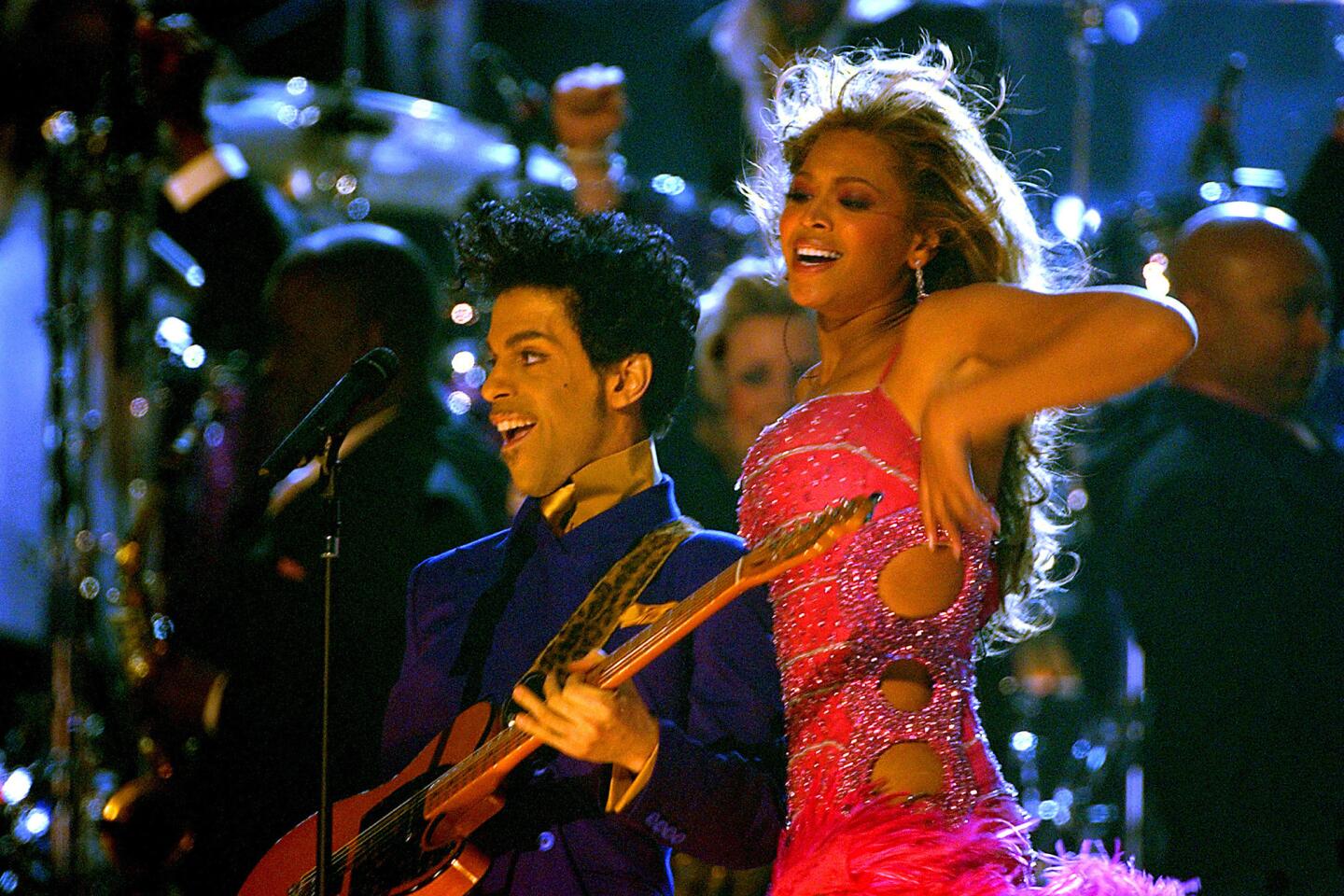

From the Beatles and Bob Dylan to Beyoncé, Prince sits within a spectrum of musicians who have deployed the tools of cinema in service of their creative expression. Where many of his albums feature the rather staggering credit “produced, arranged, composed and performed by Prince,” that level of self-contained creativity simply cannot be transposed onto conventional feature filmmaking, an enterprise that demands many collaborators both in front of and behind the camera.

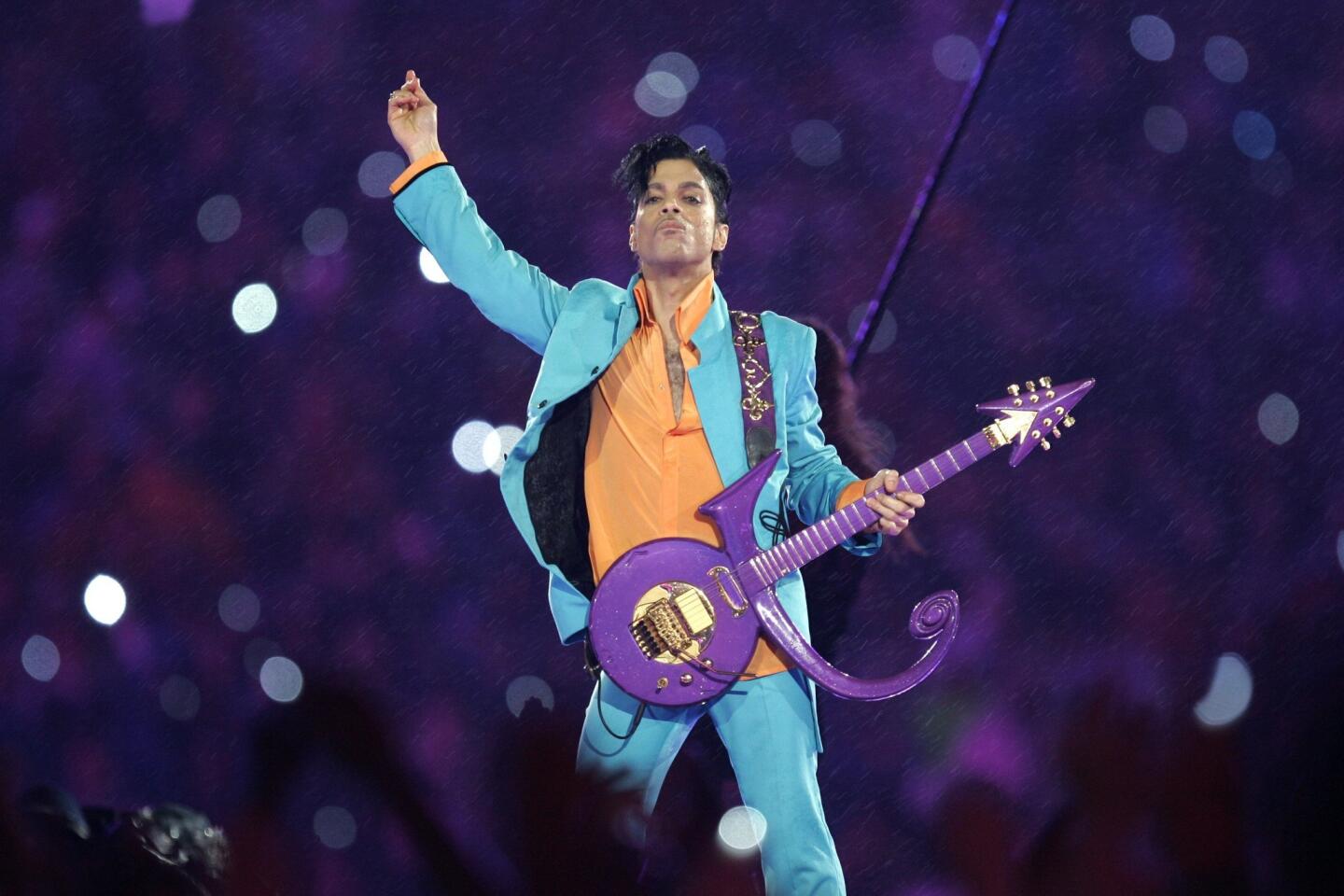

Yet in his multiple forays into movies, Prince sought to create a melding of music and image as distinctive and exploratory as the rest of his work. In “Purple Rain,” he willed into being what has emerged as one of the definitive movie musicals of the modern era, while in the three films he directed, “Under the Cherry Moon,” “Sign o’ the Times” and “Graffiti Bridge,” he tried different ways to strike a balance between music and storytelling. What these pictures have most in common is their attempt to bring a viewer into a complete experience. If Prince often seemed to live within a world of his own creation, in his film work, he seemed to be inviting the rest of us to join him there.

If “Purple Rain” is the most conventional of his movies — a ficitonalized origin story that conflates biography and persona akin to Elvis Presley’s 1957 “Loving You” — it also is the most fully realized. In all four of his pictures, Prince puts himself across as some version of himself in a way that is distinct from the acting forays of musicians like David Bowie or Diana Ross.

FULL COVERAGE: Prince | 1958-2016

There was a visual component to Prince’s work right from the start. His debut album, 1978’s “For You,” credits him with “dust cover design.” His self-titled second album features a back-cover photo of the artist naked on a winged horse. That was followed by the notorious black bikini briefs on the cover of “Dirty Mind” and the shocked headlines splashed across the front of “Controversy.” His 1982 double album “1999” produced breakthrough videos for the title track and “Little Red Corvette,” made with a visual style evocative of neon-rimmed new wave noir.

All of this is before 1984’s “Purple Rain,” the film that would both make him a global superstar and firmly cement his reputation as an unknowable, enigmatic genius. Prince does not have a directing, producing or screenplay credit on the movie — Albert Magnoli is the director — and yet it feels fully his, conjuring an origin story that is loosely based on his own biography but is fully preoccupied with the making of the Prince myth.

Prince’s character in the film — who goes only by the Kid — is a difficult and complicated musician working out his issues on the stage and often taking it out on those around him, loved ones and bandmates alike.

If Prince presented himself as a tortured soul in “Purple Rain,” his turn in 1986’s “Under the Cherry Moon” spotlighted the cheeky, playful side of his personality. Most of all, Prince seemed to want to have fun, crafting something that was a funky time-warp version of a Champagne fizzy 1930s musical comedy.

Prince plays a musician named Christopher Tracy who spent his time hustling rich women in the South of France; the film also marked the feature debut of actress Kristin Scott Thomas. Prince took over directing duties when Mary Lambert, known for her work on music videos with Madonna, left the project. The film’s luxurious spaces and black-and-white look were the creation of production designer Richard Sylbert, who also worked on movies such as “Chinatown” and “The Cotton Club,” and cinematographer Michael Ballhaus. Ballhaus made his name working for the roguish German director Rainer Werner Fassbinder and was just beginning what would prove to be an ongoing collaboration with Martin Scorsese, which would soon result in “Goodfellas.” (Imagine that run of collaborators: Fassbinder, Scorsese, Prince.)

“Under the Cherry Moon” was largely seen as a work of ego and vanity when it was released, but Times critic Michael Wilmington in his original review declared Prince “a promising first-time director” and wrote that the film’s lopsided ambitions “revealed him as someone fascinated with artistic risk.”

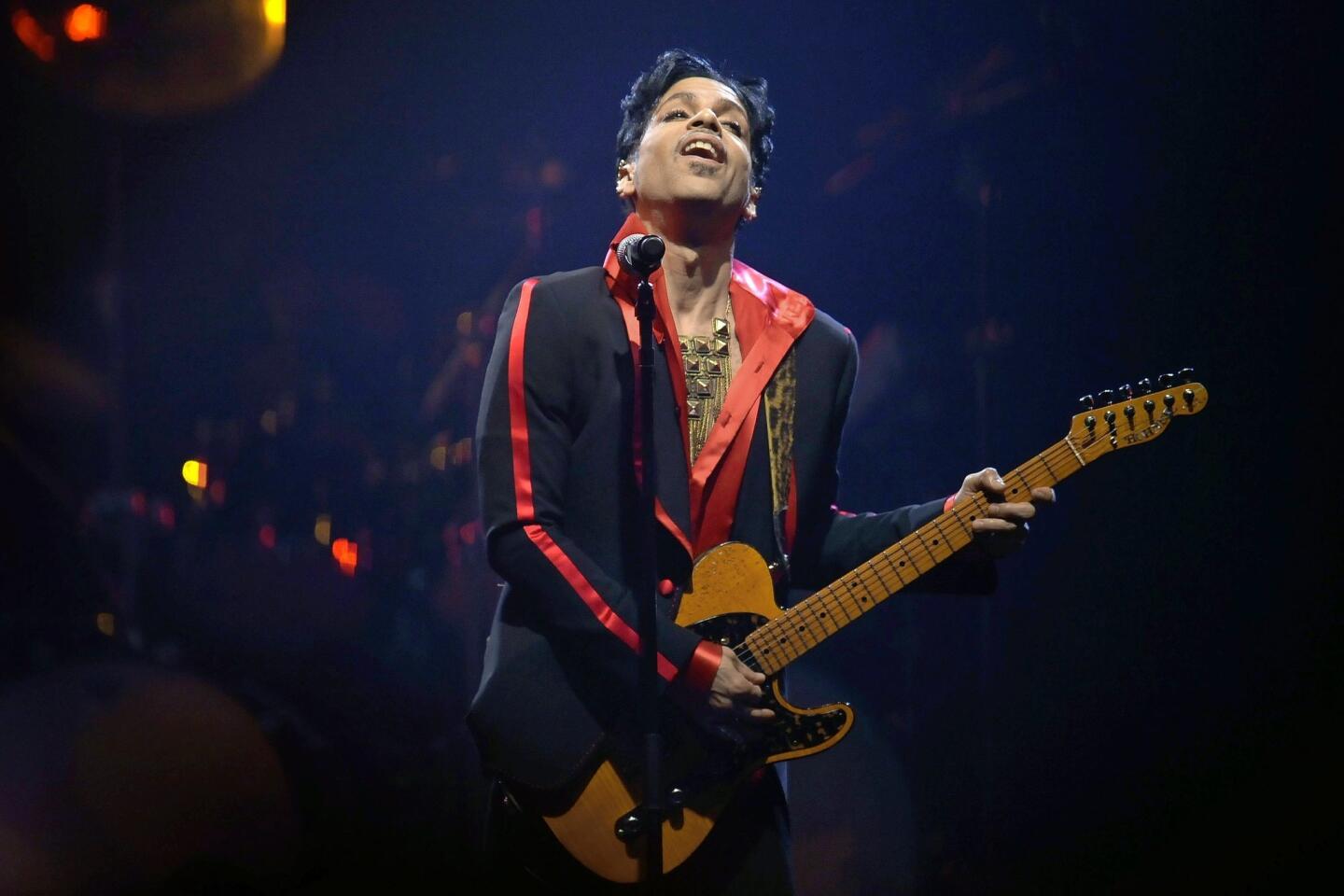

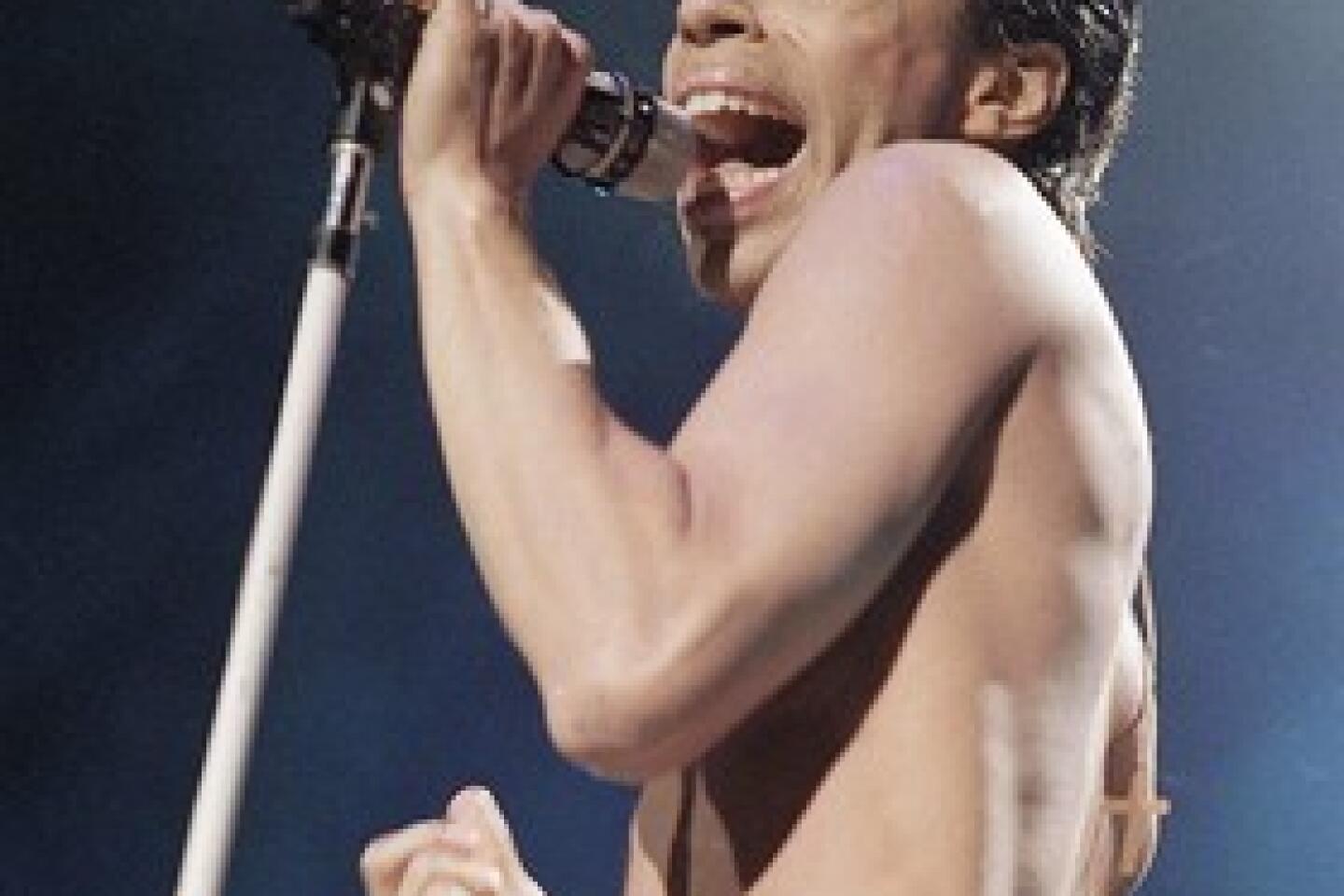

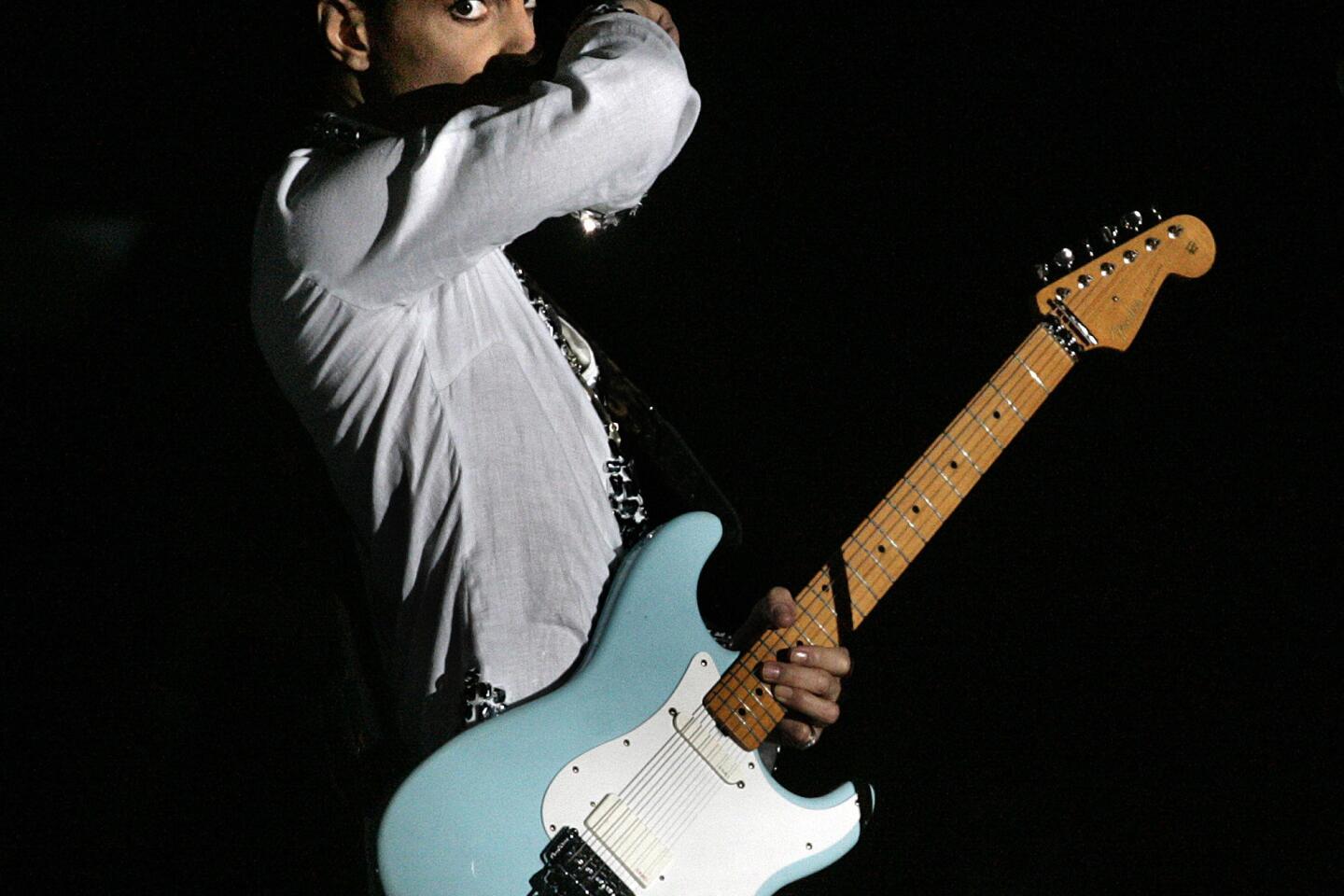

Prince would again take the director’s chair for the 1987 concert film “Sign o’ the Times,” which was made in support of the double album of the same name. The movie takes the peach-and-black color palette and art-directed clutter of the album’s cover and makes it into a broader reality. There are scattered moments of vague storytelling, dialogue delivered among Prince and his bandmates or brief fantasy interludes, but the film is first and foremost a thrilling, up-close document of the artist’s magnificent charisma and his abilities as a bandleader and performer.

Prince would provide songs for Tim Burton’s 1989 adaptation of “Batman,” and the soundtrack album almost functions as some alternate narrative to the movie. The album credits assign songs to different characters, as if the inner torment of Bruce Wayne and Batman mirrored Prince’s preoccupation with the struggle between the secular and the spiritual, sexuality and faith. He also seemed to feel a kinship with the unleashed id of the Joker, and so, Prince being Prince, he transformed the movie’s duality struggle into a kinky three-way.

1990’s “Graffiti Bridge,” again directed by Prince, seemed to be an attempt to take the baroque anti-naturalist visual style of Burton and use it for a sequel/vague retelling of “Purple Rain.” Though it feels like his weakest film, Prince was trying to find another way to balance music and narrative, again including longer song and dance performances, as a way to amplify the sense of existing within a complete and self-contained realm.

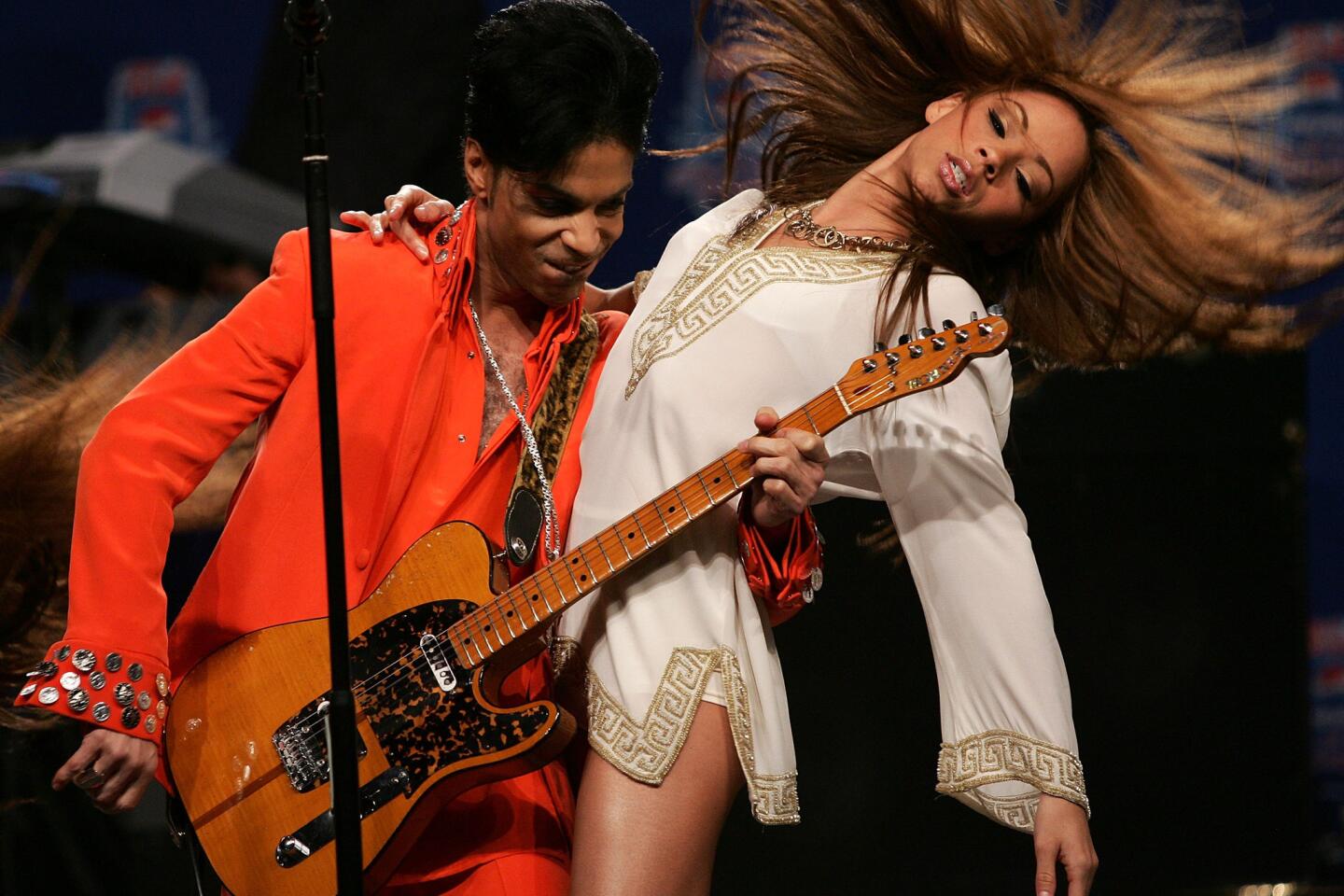

Just days after Prince’s death, Beyoncé released her new album, “Lemonade,” preceded as part of its tightly choreographed launch by the debut of a visual album of videos to go along with it. Beyoncé is credited as the project’s executive producer and one of seven directors. Like Prince before her, she has become an artist and performer so brimming with ideas drawn from such a wide range of influences that music alone cannot express them.

In his own filmmaking work, Prince sought to explore a language in which music and image merged into something more, each elevating the other. From “Purple Rain” as a narrative with concert footage to “Sign o’ the Times” as a concert with a loose narrative and his experiments in between, Prince at the movies was a uniquely powerful artist in his own right. Just as he seemed able to pick up any musical instrument and make it his own, so too was he able to make his own personal and idiosyncratic statements from the tools of filmmaking.

Twitter: @IndieFocus

MORE

Prince backing band the Revolution will reunite

Public memorial for Prince set for May 6 on L.A. City Hall south lawn

Prince’s sister claims the singer had no will

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.