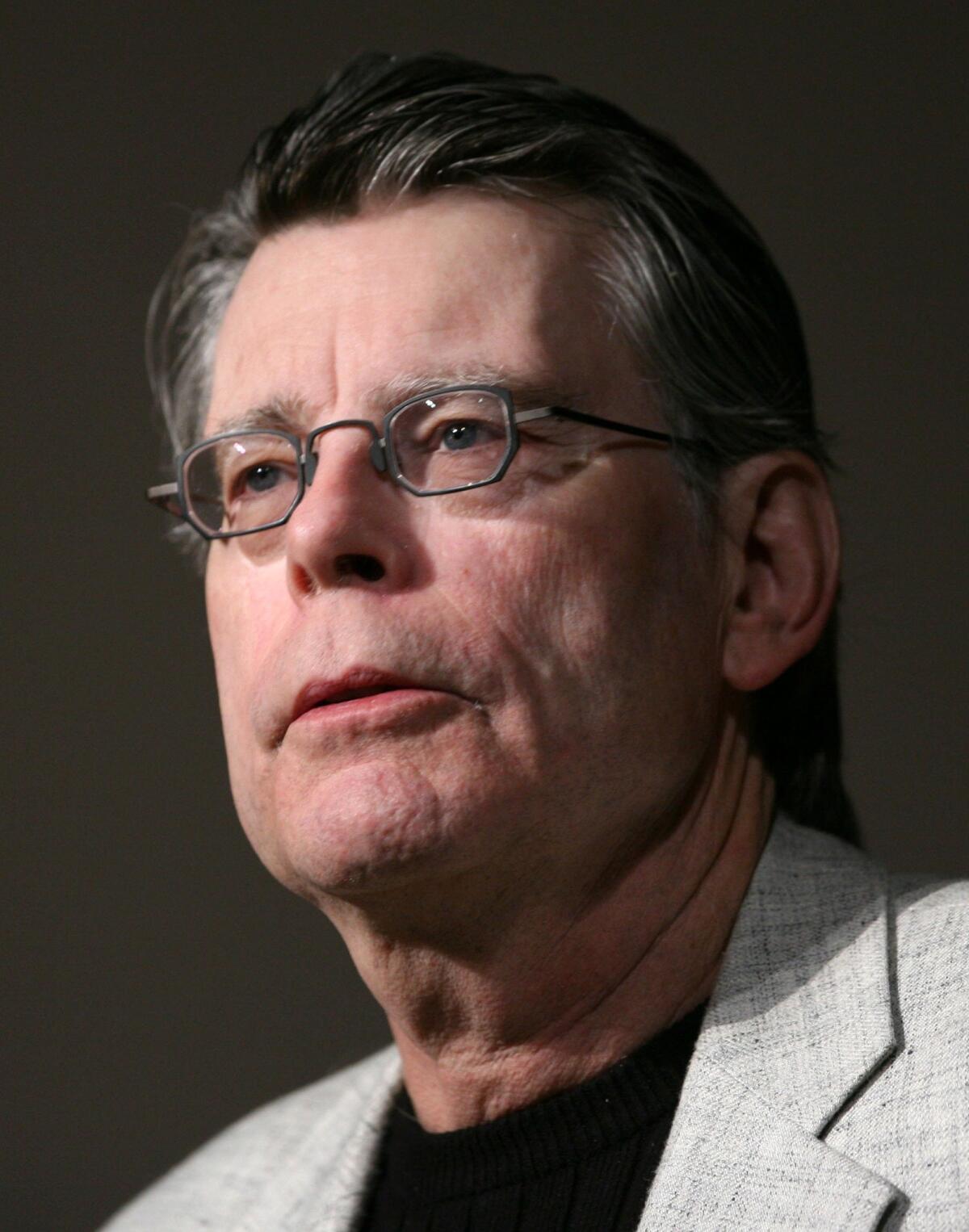

Q&A: Original ‘Pet Sematary’ director Mary Lambert on Madonna and Stephen King meetings at Denny’s

- Share via

In 1989 director Mary Lambert brought Stephen King’s celebrated bestseller “Pet Sematary” to the big screen, spinning its tragic tale of grief gone wrong into a box-office hit that cemented a terrifying toddler, a cat named Church and lines like, “Sometimes dead is better” into the annals of horror history.

Lambert launched her career directing music videos for the likes of the Go-Gos, the Eurythmics, Sting and Janet Jackson and made her feature film debut with the 1987 experimental art-house flick “Siesta,” starring Ellen Barkin as a daredevil skydiver interrogating her own life and relationships.

The Arkansas-raised Lambert, who studied painting at RISD, developed a visual style highlighted by evocative imagery and saw some of her most fruitful early collaborations with Madonna (“Borderline,” “Like a Virgin,” “La Isla Bonita”), whose provocative “Like a Prayer” music video sprang out of ideas the two brainstormed while driving across Hollywood one night.

Those works helped her land the big studio break of her career. In the spring of 1989, just over a month after premiering “Like a Prayer” to protests from the Catholic Church — and a call for boycott from the pope himself — Lambert made her studio debut directing “Pet Sematary.” Starring Dale Midkiff as Louis Creed, Denise Crosby as Rachel Creed and Fred Gwynne as Jud Crandall, it notched a No. 1 opening.

She would return to direct 1992’s “Pet Sematary II” after losing a battle to center the follow-up on Ellie Creed, the young female character from the first film. But Lambert has fond affections for the sequel, which earned a cult following years after release, and recently gave her blessing to Paramount’s new “Pet Sematary” remake directed by Dennis Widmyer and Kevin Kölsch.

“My career is really littered with the projects I wanted to do that were about women,” says Lambert, who shrugs off even those discouraging Hollywood moments with a matter-of-fact lightness and dry wit. “They all got thrown back at me because most of the time it was like, ‘We can’t do this with a female protagonist.’”

Lambert has now helmed more than a dozen features for film and television and recently oversaw the remastering of “Pet Sematary’s” 30th anniversary Blu-ray release for Paramount. She phoned from New York to discuss the horror classic, meetings with King at the Denny’s in Hollywood, the state of the industry for female directors and her future female-led projects.

Going into horror wasn’t exactly your career plan when “Pet Sematary” came along. What enticed you about the story of Louis Creed, a father who makes a fateful choice when unfathomable tragedy strikes his family?

I could just see it the way I was able to see fairy tales when I was a little girl — how this beautiful family would have this beautiful, idyllic house, but under the surface there would be this horror because of the bad decisions that Louis [Creed] makes. It was also the idea of obsession and obsessive love, which is what “Siesta” was about. Because I do believe in hauntings. When a spirit lingers, it’s because the spirit can’t move on, and that’s real for me.

You’ve felt this yourself, in real life?

There are places that are haunted. Have you ever been to one of those big, tourist attraction kind of plantations in South Carolina where they preserve the slave quarters? You walk through those grounds and you feel the pain, you feel the spirit of things — bad things, evil things — that haven’t been erased from the consciousness of the world, and the consciousness of the place. I believe that death is a cleansing and a moving on. You change. When people die, they move on — and if they don’t, it’s a problem.

ALSO: Our original 1989 ‘Pet Sematary’ review — ‘compelling and disturbing’ »

[“Pet Sematary”] also touched on things I strongly believe in. You have to let go — and that extends into life. When it’s time for a relationship to end sometimes you just have to let go of it or it becomes a wound. Somebody else might see something different in the material. Somebody else might enjoy the movie and none of these things would occur to them! That doesn’t matter. I think if a movie or a piece of literature has a strong subtext, even if that’s not what the audience thinks about when they’re watching or reading it, it still informs their enjoyment of the piece.

Landing “Pet Sematary” you had to go through one major gauntlet: Getting the approval of Stephen King over meetings at … Denny’s?

That was one of his favorite places. My first meeting with him was in New York, but our subsequent meetings were at Denny’s. I don’t eat meat, so it would have been the Grand Slam breakfast without the bacon for me. I think Stephen was mostly interested in the burgers. That’s my memory! It was the one on [Sunset] Boulevard and Gower Street. I think it’s also that those are the characters he writes about — the kind of characters who would be at Denny’s.

“Pet Sematary” was the novel King said scared him the most, but it was also the first screenplay he adapted from one of his own books. How did working with him help inform your telling of the story?

This was a very personal story for him. He told me that early on: His son ran out in the road, and he ran to get him out of the road as a truck approached and the entire story flashed into his head in those few minutes. It was his insistence that we shoot it in Maine, and I think that ended up being a very important part of the film because Maine is very beautiful but the woods are dark and scary and they encroach on everything. Nature was all around, and it was a real visual influence.

And you got a great cameo out of him playing the preacher at the funeral.

I loved the way he looks! I really wanted to have him do a cameo because I knew how much it would mean to his fans, but I also didn’t want to do it in such a way that it wouldn’t work for the movie. But he has a great voice, and I could just hear him intoning the words. Somewhere in a vault there is Stephen King performing that entire funeral service. They should get it out and get a million hits on YouTube for that one.

Over the span of a few months in 1989 you drew the ire of the Catholic Church with Madonna’s “Like a Prayer” video and directed “Pet Sematary,” which featured a zombie cat named Church. Cosmic poetry, or coincidence?

It was just a perfect storm! Madonna and I, by that time we were really solid friends and we really trusted each other. We had dinner together one night and she said she wanted me to direct a video for “Like a Prayer.” We got in whatever black Mercedes she was driving at the time and just drove around Hollywood. We drove up to Mulholland and we listened to the song, just driving around Hollywood, pumped up on her car stereo.

I’m like, ‘Wow, this is a song about how sexual ecstasy mirrors religious ecstasy.’ And she was like, ‘Yeah! And I want to [have relations with] a black guy on the altar!’

The resulting imagery ended up being groundbreaking as social commentary: The burning crosses, black Jesus, setting it in a church.

In the Catholic Church it has to go through the priest: You can’t even pray directly to God, you have to go through the priest and the priest prays for you. It’s all very patriarchal.... God talks to the priest, the priest talks to the man, and the man tells his wife what to do. The women are right at the very bottom, down there with animals in terms of any kind of freedom of speech or expression.

That was all part of the dialogue. We wanted to take certain things that are a given or a convention and say, why couldn’t it be this? Why couldn’t Jesus be black? Why can’t sexual ecstasy be equated with religious ecstasy? Is it wrong to enjoy sex? Is it wrong to enjoy prayer, for that matter? Why does it have to be a dull or confining thing? I knew there was going to be some controversy but I wasn’t prepared for how much. It was fun.

One of “Pet Sematary’s” most powerful moments is the scene in which you convey an unthinkable act in just four shots — we see Gage run into the street, we see the truck, his kite floats up toward heaven, and we see his shoes.

That was storyboarded by my friend Andrea Dietrich. With a scene like that you’re not going to actually shoot it … you have to figure out what sequence of images are going to tell your story. The sequence where Gage comes out from underneath the bed, and first he slices Fred Gwynne’s ankle and then he bites him in the throat — that was done with a whole lot of different techniques. We had a little puppet hand with a scalpel in it, then we used the real child to come out from under the bed and jump on Fred. The actual head that bites his throat is a puppet, because obviously I didn’t want to inflict that on [Miko Hughes]. Talk about karma coming back to haunt you!

Miko was a toddler then. Have you stayed in touch with your “Pet Sematary” family?

I’ve stayed in touch with Miko, and saw him about three or four years ago. He’s an adult, he had a pretty stellar career as a child actor and he continues to act but he’s been directing some too. And he barely remembers [“Pet Sematary”], so I feel like I didn’t irrevocably scar him. But Denise Crosby is one of my best friends. We have so much fun together. We truly still love each other. I see Dale Midkiff every once in a while, and I see Fred Gwynne in my dreams. I’m really sad that he passed away.

After “Pet Sematary” you directed “Pet Sematary II,” a sequel I loved, which took a different approach to this place where dead things come back, with teenage protagonists and new perspectives on loss and longing.

Thank you! That movie didn’t get as much love as it should have. I wanted to make an irreverent movie that had a lot of dark humor in it. I knew it was not going to be as scary as the first movie because we didn’t have Stephen [King]’s involvement.. So I went for that from the very beginning. What is the worst thing that could happen to a 12-year-old boy? What if his mother marries the hard-ass sheriff, and the hard-ass sheriff in town becomes your stepfather? But actually, no: what’s worse is if the sheriff dies, you bury him in the cemetery, and he becomes a zombie! And now you have a hard-ass sheriff zombie as a stepfather. Honestly, that’s funny to me.

You cast Eddie Furlong and Clancy Brown in what are now iconic roles within the horror world. How did that cast come together?

I cast Eddie [Furlong], Clancy [Brown] and Anthony Edwards … but they wouldn’t spring for another Hollywood actor; we had to cast this other young boy Jason [McGuire] in Georgia who had never acted before, but he did a really good job.… The sheer physicality of that movie was a lot of fun for me. When Clancy fights the dog, there was a real dog and a puppet dog, and then it was all Clancy. He was a puppet master with that dog.

ALSO: Our original 1992 ‘Pet Sematary II’ review — ‘rife with teen trauma’ »

I really wanted to do a soundtrack that was nothing but electric guitar, I wanted it to be really raw, picking up where the Ramones left off — and I couldn’t sell that to the producers. They freaked out.

That wasn’t the only pushback you got on the sequel: Your initial desire to focus on Ellie Creed, the young daughter who survives the events of the first “Pet Sematary,” was met with resistance to the idea of having a female protagonist lead the story. That sounds a lot like the debates we’re still seeing about women in Hollywood today.

Yep, we still are. We’ve made a little progress but not enough. My career is littered with the projects I wanted to do that were about women — not, like, “girl movies” but crazy, baby-killer psychopath women, or women in combat movies. They all got thrown back at me. Most of the time it was like, ‘We can’t do this with a female protagonist.’ ‘We have to make the male part bigger.’ ‘When she goes into combat, the guy’s got to save her.’ I’m like, that’s not the movie!

I think it’s changing a little bit. There are Ghostbusters that are women. Charlize Theron was in “Mad Max.” It’s changing, but not fast enough.

From your video work, including the Janet Jackson two-fer of “Control” and “Nasty” through “14 Women,” your 2007 documentary about women in Congress and even the recent episode of “Step Up: High Water” you directed, do you see a throughline linking the kinds of stories you are drawn to?

The most recent thing I directed was an episode of “Step Up” which is on YouTube now, and it has all of the things in it — it’s about diversity and inclusion and it has some really strong female characters as well as strong male characters. I have two new projects… one is about two warring covens of witches — it’s like gang warfare, only they’re covens and it goes back centuries, it’s set in 1920 New York City, and I’m super-excited about it.

The other project is about killer mermaids. I’ve been fascinated with mermaids for a long time — I wanted to do a movie that was a more accurate telling of the Hans Christian Andersen story of the Little Mermaid. The mermaid is destroyed by the prince that she gives everything to; I wanted to use that as the first act and have her come back for revenge! But I never got that project off the ground. This project is based on a very successful novel by Mira Grant called “Rolling in the Deep.”

RELATED: Has horror become the movie genre of the Trump era? »

I’m also doing a documentary that’s a follow-up to “14 Women” about a woman named Yulia Tymoshenko, who’s running for president of the Ukraine. The last time she ran for president she lost an election that most people think she was frauded out of, and [Viktor] Yanukovych put her in prison for two years after Paul Manafort was hired by the Russians to run a smear campaign against her. Does that sound familiar? Does “Lock her up” sound familiar?

Those are the stories I want to tell. I want to tell stories where women have agency. That doesn’t mean that they’re just a part of the plot, they’re not just girlfriends or mothers, which are both important things to be, but I think women’s stories are important.

If you look at the statistics of women directing feature films, it really went down for a while. It got bleaker for a while. But I think it’s coming back. And it’s because there are some really talented women out there that are having successes … and that’s incredible — it helps all of us.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.