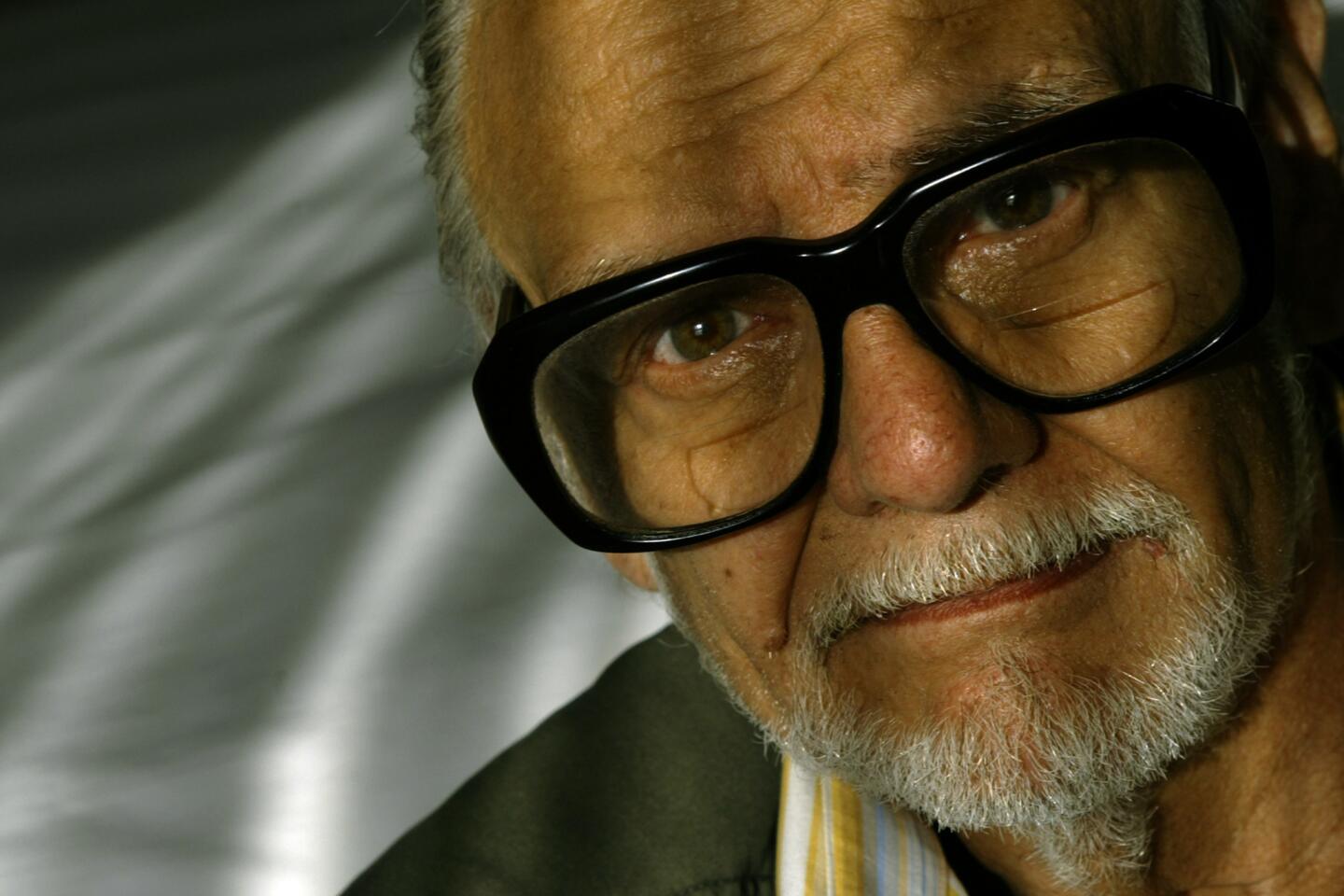

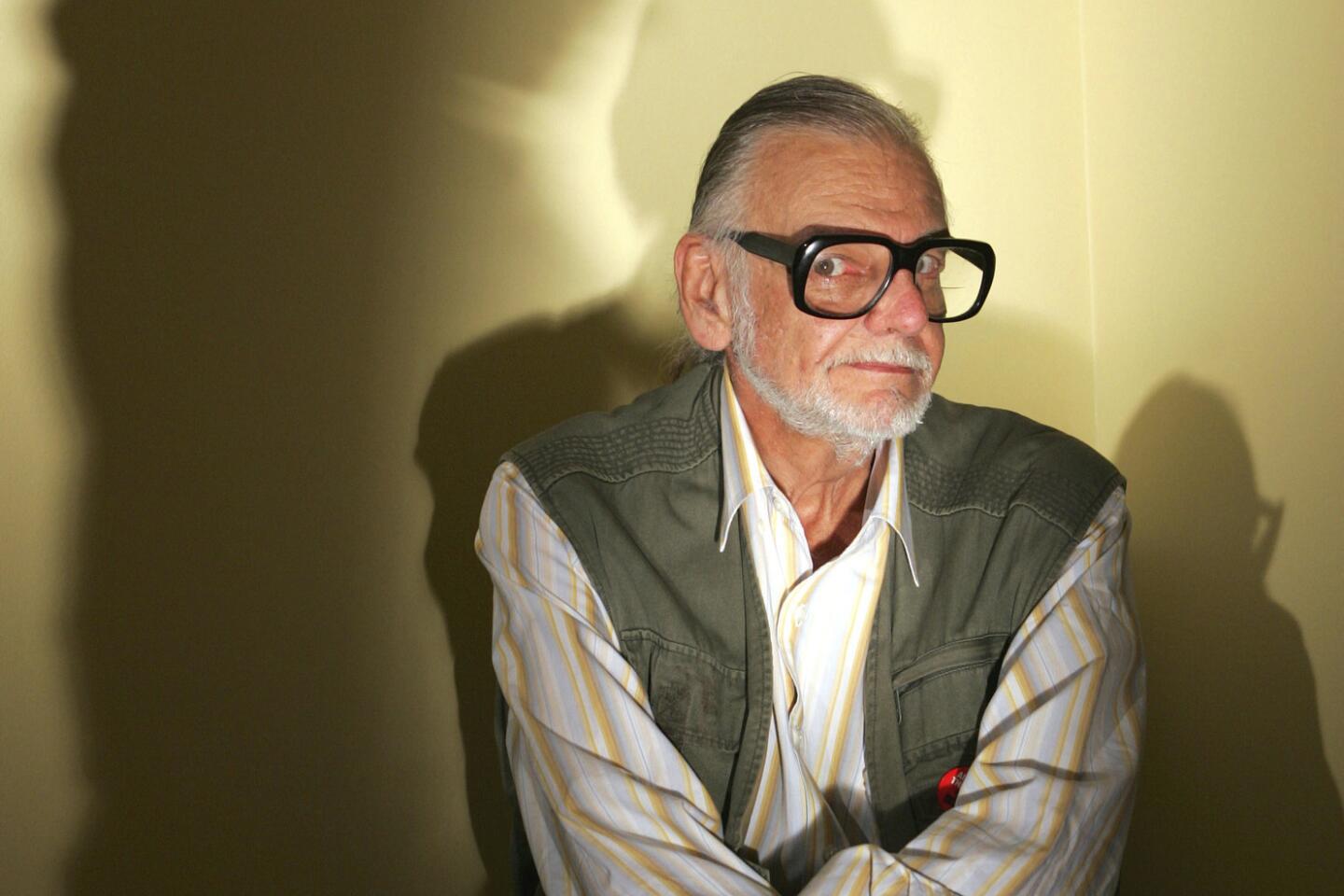

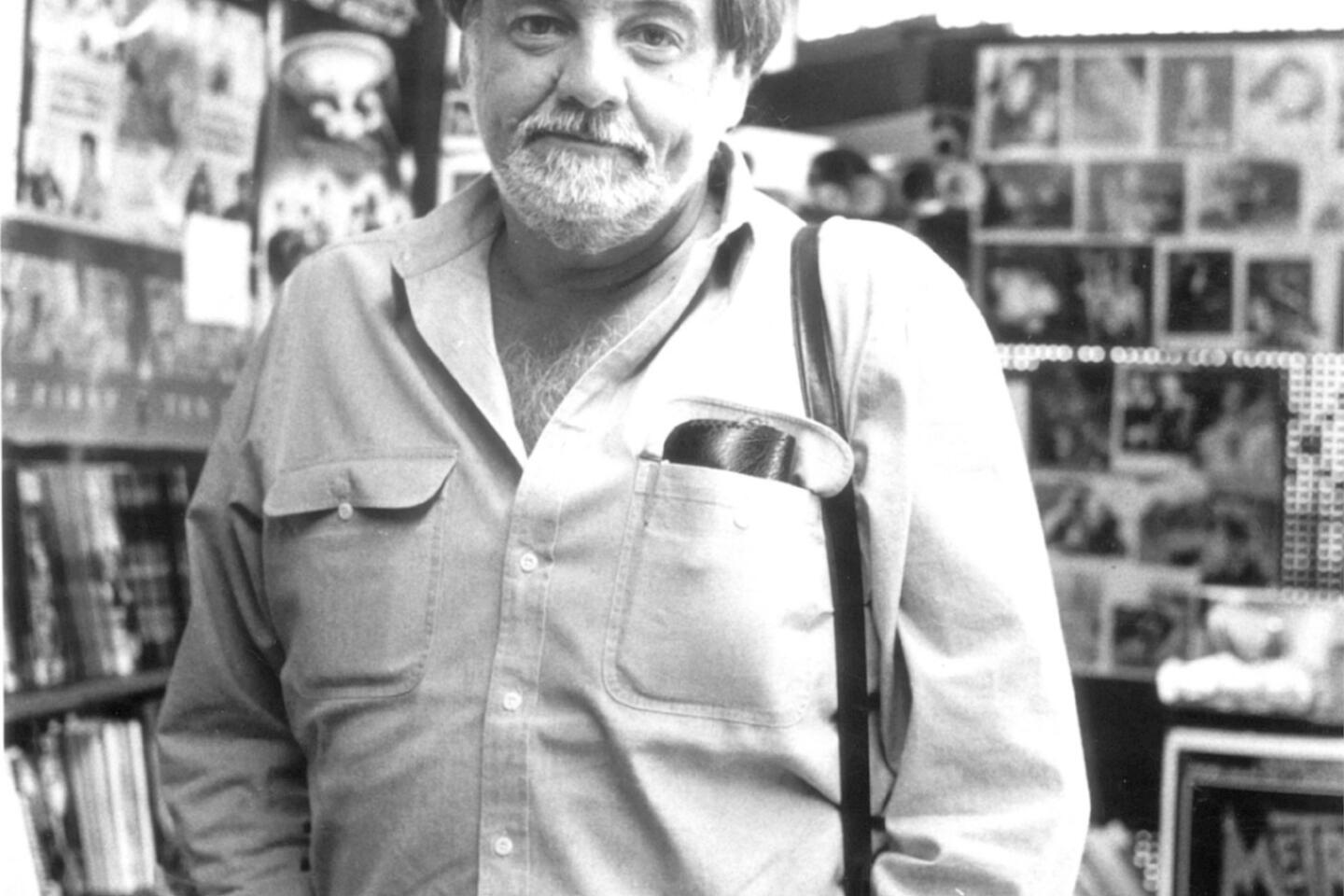

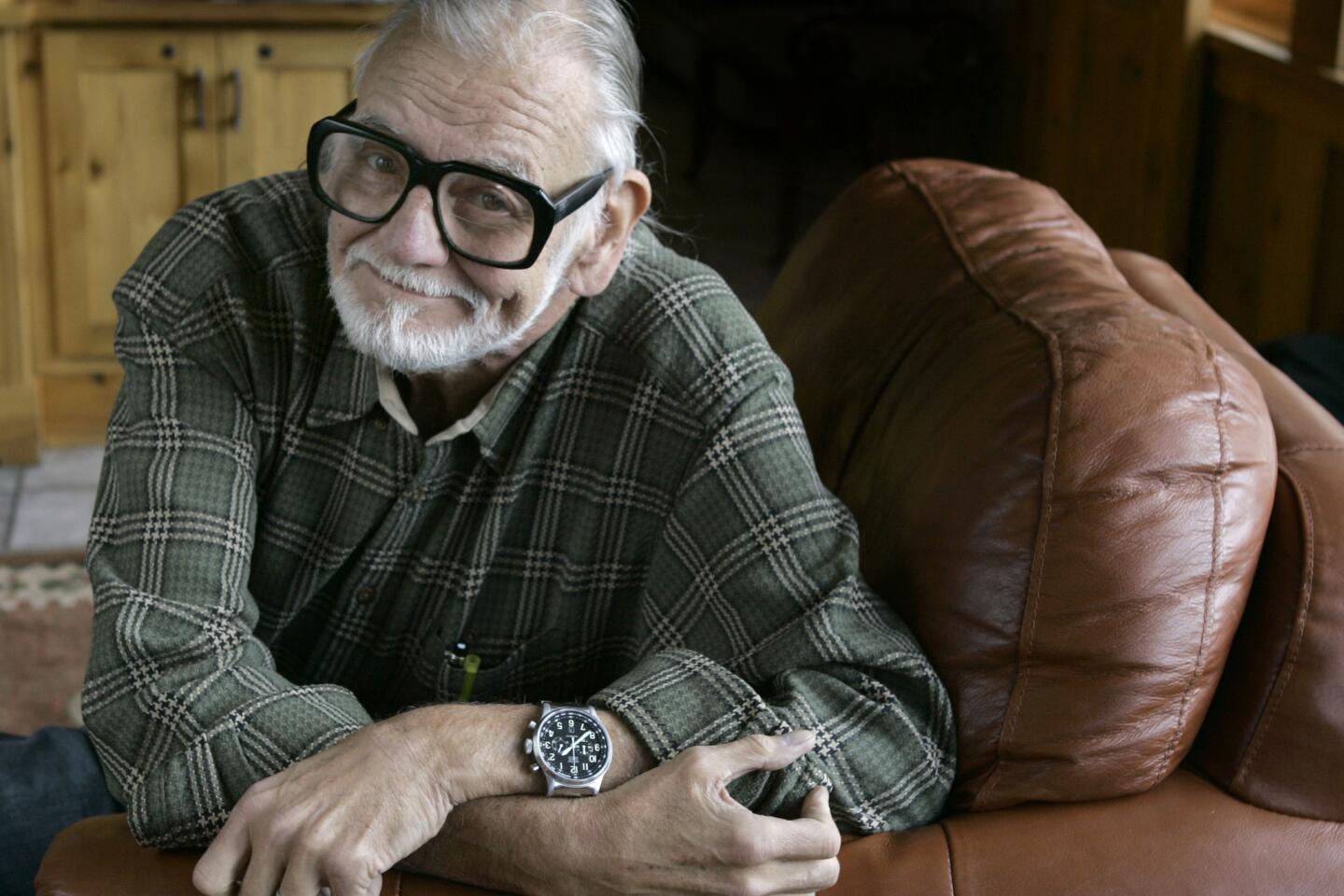

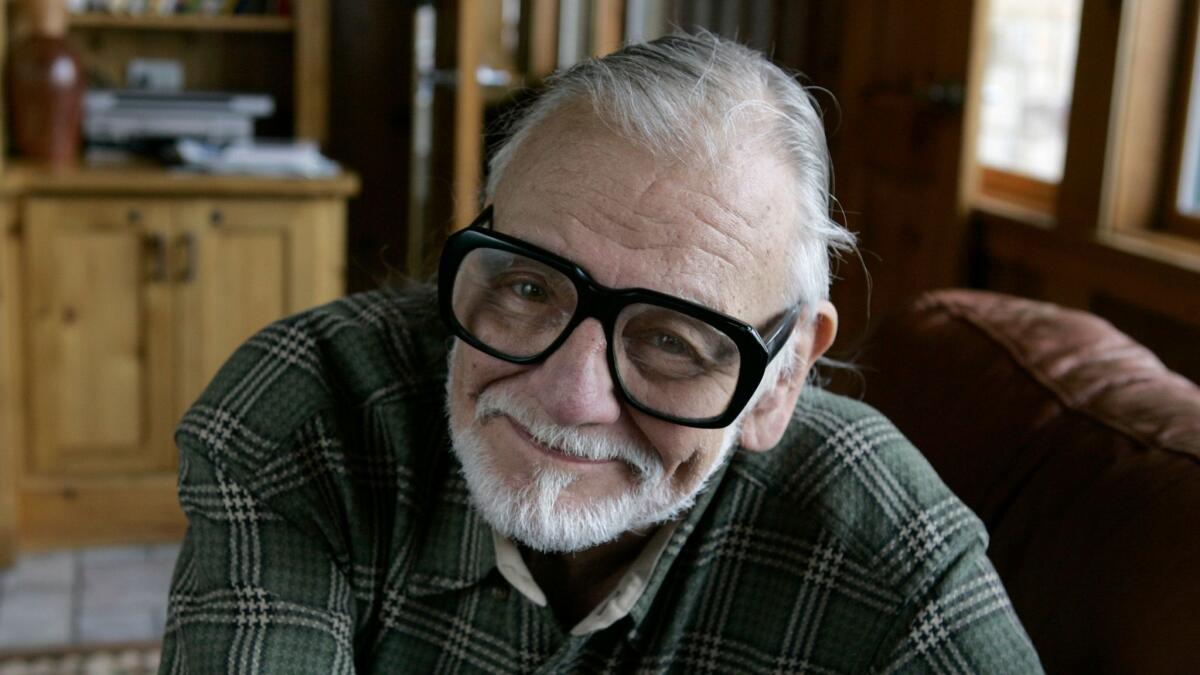

Appreciation: George Romero, godfather of gore, brought zombie cinema to life

- Share via

The dead walk so freely across our screens these days that it can be hard to recall a time when their appearance was a shock — when the sight of a single rotting, reanimated corpse, let alone a slowly advancing horde of them, could deliver a genuine frisson of terror. Or, for that matter, when this eerie spectacle still felt rich, even full to bursting, with metaphoric possibilities. From the ongoing “World War Z” movie franchise to the ever-popular series “The Walking Dead,” from the hilarious “Shaun of the Dead” to the rather less inspired “Zombieland,” screen zombiedom has become its own self-perpetuating epidemic.

Good, bad and indifferent, it’s all testament to the legacy of George A. Romero, one of a few filmmakers who not only shaped a storytelling tradition, he virtually breathed it into being.

And well before his death on Sunday at the age of 77, Romero, a consummate independent filmmaker and natural-born Hollywood skeptic, was not exactly timid in expressing his disapproval of the zombie renaissance his work had inspired.

He lamented the “Hollywood-ized” feel of “World War Z” and dismissed “The Walking Dead” as “a soap opera with a zombie occasionally,” noting that both works had made it nearly impossible to get an edgier, lower-budget zombie movie financed. He likened Zack Snyder’s proficient 2004 “Dawn of the Dead” remake to a “video game” and criticized its fast-sprinting zombies (in lieu of Romero’s famously slow, shuffling ones).

Some might argue that, like most genre pioneers, this master of modern horror had only himself to blame. When you create something as perfect and unforgettable as Romero’s 1968 monochrome masterpiece, “Night of the Living Dead,” and follow it with five sequels over the next four decades, imitators of every kind are only to be expected.

“Night of the Living Dead,” which Romero directed, co-wrote (with John Russo), shot and edited when he was only 28, was hardly the first zombie movie; that precedent is generally credited to the 1932 picture “White Zombie,” starring Béla Lugosi. But it was the first to conceive of a zombie uprising as a kind of homegrown apocalypse, the first to summon the dead from the grave en masse and set them on a lethargic but tireless quest for human flesh.

In Romero’s hands, a creature once rooted in far-flung exotic realms of voodoo and mysticism had suddenly materialized, with shocking immediacy and no warning whatsoever, in America’s backyards.

Filmed on a tiny $114,000 budget near Pittsburgh (where most of Romero’s movies were shot), with unknown actors and a bare-bones technical rawness that give it the feel of an unvarnished nightmare, “Night” offered an irreducible metaphor for a country swallowing itself alive. Its pitiless violence spoke powerfully to an era that, still reeling from the casualties of Vietnam and the assassinations of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., President John F. Kennedy and Robert F. Kennedy, had become all too inured to the reality of senseless killing.

The movie’s parting shot — in which its protagonist, a black man named Ben (played by Duane Jones), is mistaken for a zombie and gunned down by vigilantes — remains one of the most racially and politically charged moments in horror cinema, and one that has only gained resonance. It was, as it is now, a prescient reminder that whatever may come clawing at our boarded-up windows, there are few truer monsters than men armed with guns, an unexamined sense of supremacy and a seemingly righteous cause.

That a zombie plague can be a vehicle for social critique is no longer the stuff of revelation. Nor, for that matter, do zombies hold a horror-monopoly on subtext, as evidenced by movies as different as “Rosemary’s Baby” (released the same year as “Night of the Living Dead”), this year’s “Get Out” and the dread-soaked thrillers of the Japanese director Kiyoshi Kurosawa. But it is difficult to think of another filmmaker who has so consistently and ingeniously exploited the sociopolitical underpinnings of his chosen bogeyman, particularly within the context of a single film series.

He was, to some extent, the victim of his signature achievement. The “Dead” films inevitably overshadowed the other projects that Romero tried his hand at over his career, including 1973’s “Season of the Witch” and “The Crazies” (both of which would later be remade) and 1981’s “Knightriders,” a rare non-horror Romero film that was an eccentric and lovingly crafted drama about a motorcycle-riding Renaissance festival troupe starring Ed Harris and Romero’s then-wife, Christine Forrest (with a cameo by fellow horror maestro Stephen King).

Perhaps the most original and fully realized of these one-offs was “Martin” (1978), a disturbing, beautifully edited rethink of the vampire myth, which Romero would later single out as his personal favorite among his films.

The same year as “Martin,” Romero made a brilliant return to the “Dead” zone with “Dawn of the Dead.” Substituting a bright-hued commercial slickness for “Night’s” black-and-white realism, the film turned an abandoned shopping mall into a glorious chase-thriller playground and a diabolical symbol of American consumerism run amok.

It also showed that Romero could pivot easily from stark horror to wickedly pungent satire. (I still remember making the wonderful mistake years ago of watching “Dawn” by myself at night and cackling to myself when I wasn’t cowering under the blankets.)

The remaining four films in the cycle may not have reclaimed those early highs, but with perhaps the exception of the tiresome if amusingly titled “Survival of the Dead” (2009), they are thoughtful, elastic and splendidly gruesome achievements in their own right.

“Day of the Dead” (1985), a grim, claustrophobic portrait of scientists and soldiers under zombie siege, was wanly received on its initial release, but its unsparing nihilism and ferociously eruptive splatter feel all the more forceful and uncompromising today. The moribund conventions of the found-footage thriller felt pretty worked over even before “Diary of the Dead” arrived in 2007, but that fifth installment, shot mostly on handheld digital cameras, remains a fleet, funny and inventive interrogation of our increasingly screen-obsessed culture.

The best of the post-“Dawn” movies is “Land of the Dead,” an exuberant late-career triumph that I lined up, alongside several Romero die-hards caked with fake blood and gray zombie face paint, to see at its world premiere at the 2005 CineVegas film festival. The movie was worth dressing up for, a satisfyingly splattery vision of class revolt that anticipated the Occupy movement six years early and, like “Night of the Living Dead,” cast its deepest sympathies with a black man (this time a hulking zombie leader called Big Daddy, played by the Canadian actor Eugene Clark). In the villain’s corner was Dennis Hopper as an ivory-tower autocrat with a mouthful of George W. Bushisms and an attitude that seems positively Trumpian in retrospect (“Don of the Dead,” anyone?).

“Land of the Dead” was so savage in its attack on corrupt American privilege that it could have come only from an industry outsider, someone with a healthy disdain for the usual rules of franchise filmmaking and a principled refusal to play it safe. The iconoclasm to which Romero clung over the course of his career, as well as his insistence on creative control, meant that he rarely enjoyed the budgetary freedom he longed for, though that hardly stopped him from plugging away in his later years.

Just a few days before his death, he was unveiling early details about his next project, “George A. Romero Presents: Road of the Dead,” which he gleefully pitched as “‘The Fast and the Furious’ with zombies.” (He was planning to produce, with his longtime collaborator Matt Birman directing.) Whatever the fate of that in-the-works project, and the surely innumerable zombie movies and entertainments still to come, there is something pleasing about the idea that we still haven’t seen the last of George Romero.

ALSO

George Romero: Movies ‘are not perceived as an art form by the industry’

George Romero’s undead reckoning

George Romero, knight of the living dead, is a zombie specialist

George Romero dismisses ‘The Walking Dead’ as ‘soap opera’

George Romero found comfort in zombies, despite reluctance to return to the genre

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.