Baseball great Darryl Strawberry says he felt ‘an emptiness inside’ throughout his glory years

- Share via

If Darryl Strawberry didn’t exist, a screenwriter would need to invent him.

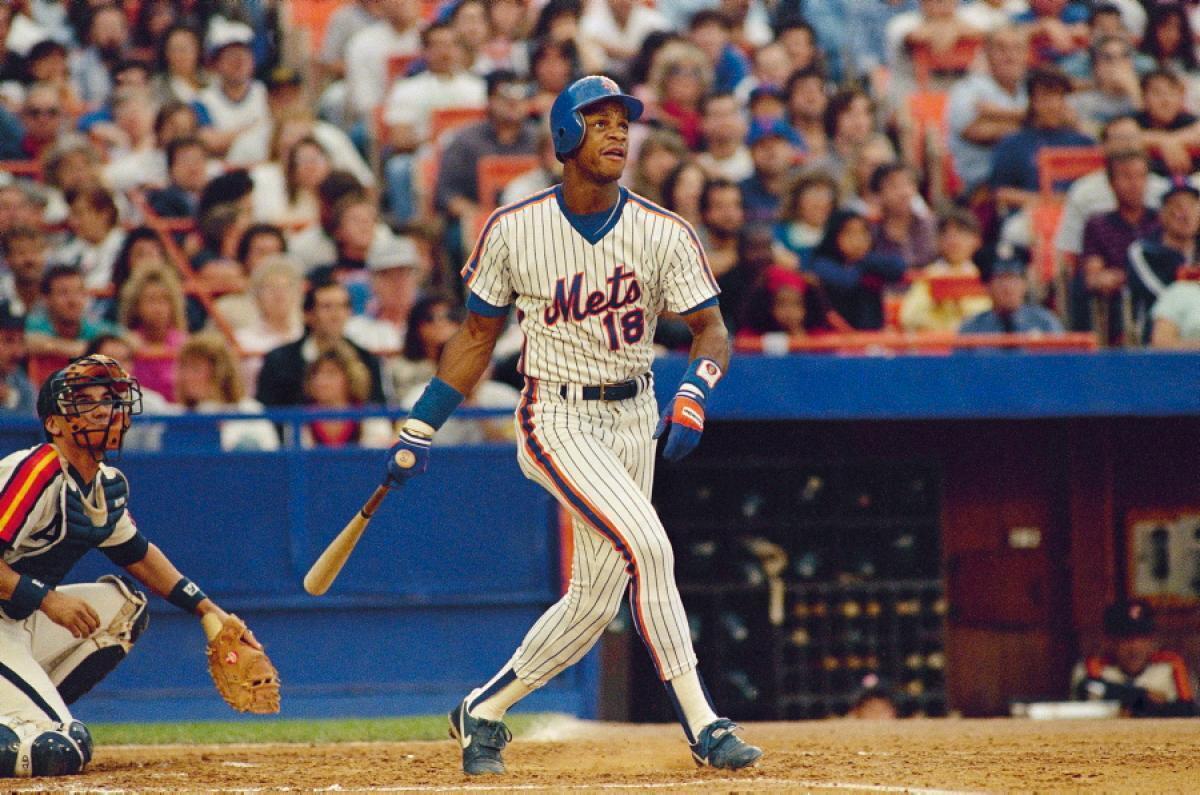

Enduring a hardscrabble childhood in South Los Angeles with an absentee alcoholic father, Strawberry found escape — and greatness — on the baseball field, thanks to a slinky swing that could quickly dispatch balls to the far side of outfield walls.

Strawberry arrived in New York as a teenage sensation in the early 1980s with a shiny future. He would go on win a rookie-of-the-year award and then, in 1986, help lead the hometown Mets to a World Series title.

That high was soon followed by a series of lows that included a long battle with drugs and alcohol addiction, jail time, an arrest on suspicion of domestic battery and multiple cancer diagnoses. Strawberry was one of the purest talents the game has ever seen. He was also one of its most tabloid-prone.

In recent years, Strawberry has rebounded, finding sobriety and a stable marriage. He’s even started a Christian mission devoted to others’ recovery.

The eight-time All-Star (and former Dodger) can now add another feather to his ball cap: screen star.

Strawberry is at the center of “Doc & Darryl,” an ESPN “30 for 30” documentary co-directed by Judd Apatow and Mike Bonfiglio. The movie looks at the rise and fall of Strawberry and teammate Dwight “Doc” Gooden with the kind of subtlety and compassion of the best scripted drama. The title subjects appear separately and together, reflecting on their journeys. ESPN debuted the film Thursday; the network will re-air it on ESPN 2 several times in the days ahead. (You can read more about the film here.)

Strawberry, who now spends most of his time in Florida and Missouri (the latter is headquarters to his foundation) spoke with The Times by phone about his colorful life and present views.

I became addicted to all of it — the womanizing, amphetamines, cocaine, being rich.

— Darryl Strawberry

There’s something so raw about this film. Was there any concern on your part that Apatow and Bonfiglio would cut too close to the bone?

Strawberry: To be honest, no. It’s everything I wanted it to be. There’s no reason to sugarcoat your life. Once you go through it in your mind and see that’s what you did, you have to show. That’s what I told [the directors]. When I walked in I said it’s gotta be real. You can’t pretend that all these things didn’t happen.

The question many fans have had over the years are the causes of your many spiralings. Can you identify the primary reasons you had so many lows?

I think growing up with dysfunction I had inside brought me a lot of pain — a pain I never dealt with. So the reality of my life became not living.

It seems fair to wonder about the role of the spotlight too — did fame make it all worse?

It wasn’t the fame. It was the fun. I’m 21, 22, 23, and at that age you never think your life can be derailed. So I became addicted to all of it — the womanizing, amphetamines, cocaine, being rich. And then as you get older you realize you have everything, but you’re bankrupt inside. You’re never free; there’s always an emptiness inside. I used to go and sit in my $2-million dollar home and feel empty. It’s all fun, and then it becomes toxic.

It’s hard to tell from the film what exactly made you finally able to get clean after so many relapses. Are you able to describe what did it?

It’s because I realized the gift I had as a baseball player didn’t make me a man. It just made me a baseball player. I had to take off the uniform to become a man. Most celebrities can’t remove the uniform. They can’t remove the film or the music or whatever made them famous. That’s why they end up going down this road. When you keep chasing old memories of who you used to be, you can never become who you can be.

Dwight knows my struggle is real, because he’s had the same struggle. We ended up in the same places, the institutions and the jails.

— Darryl Strawberry on Dwight Gooden

Do you have a sense that this all could have ended more tragically for you? Watching the film, it reminded me of how many struggles you had, how deep they were, how dangerous they were.

The life I lived should have killed me. There were multiple times when I know I shouldn’t have lived. I should have been dead. I lost a left kidney. Cancer. Drugs. Alcohol.. For some reason God had grace. I never went to school. He stopped me and said, “You’re going to do this; you’re going to preach the Gospel.” I kept running and he finally stopped me, brought me to my knees.

Is there value for you personally in getting this story out there?

I think there is. So many celebrities go through what I went through with addiction and they end up dying because they never talk about their struggles. Even people who aren’t famous. They’re hurting, living these secret lives, but they pretend they’re OK. They come outside and smile. “I’m OK.” And inside they’re dying.

On that score, I have to ask about Dwight Gooden, your Mets teammate, and the other half of this film’s equation. He’s had many of the same struggles as you. But unlike you, he doesn’t seem to have fully conquered them. What do you make of where Gooden is now?

With Dwight. I love him and I pray for him. If he’s having deep struggles I hope and pray he can overcome them. Dwight knows my struggle is real, because he’s had the same struggle. We ended up in the same places, the institutions and the jails. It’s losing something and having nothing.

It’s weird to look back and realize you actually played more years away from Shea Stadium than you did there. Were you surprised you didn’t have a longer run with the Mets — or, maybe, even regret leaving the team to return to L.A. in 1991?

I could have stayed with the Mets and not been so bitter about the organization. Lenny Dykstra moved to Philly. Keith [Hernandez] was gone, [Gary] Carter was gone. There were these young guys [instead]. The organization was headed in a different direction. I was used to playing with different personalities, different chemistry. So I signed with the Dodgers. But I wish I didn’t leave the New York area.

We had that swagger. We were vicious.... You don’t see that anymore.... Guys aren’t gritty anymore.

— Darryl Strawberry

There’s a feeling that hovers over the film of lost possibility, that given the talent on those 1980s Mets teams there should have been a longer run, more titles, if some of the missteps hadn’t happened. Do you feel that way?

There could have been more titles, I couldn’t believe we didn’t win more. I was shocked we didn’t win [the pennant] in ’88. [The Mets lost the National League Championship Series to the Dodgers in seven games.] That’s how good we were. We were the talk of baseball. It’s heartbreaking.

Besides the talent, what do you think made those teams stand out?

We were different from everybody. We had that swagger. We were vicious. We would fight with teams. You don’t see that anymore. When we got between those lines we were serious about kicking your behinds. It showed what a team is all about. We were unified and we cared about each other.

There’s indeed a lot less fighting in baseball now. But most people would say that’s an improvement. Do you disagree?

It wasn’t only about money when I played. It was about respect. It’s more civil now.

Civil is bad?

It’s more passive. Guys aren’t gritty anymore. Players are more likely to go home and sit on their boat. The [general manager] doesn’t run the team. The agent runs the team. ‘He has a sore shoulder, we don’t want to screw up his contract arbitration, don’t play him.’ What happened to ‘The team needs you’? What happened to ‘Get out there and play; you can rest in the offseason’?”

There’s also the question, especially or even after the steroid era, of which period sported the better players. Do you think guys from your time are on average better than the guys now? Who would win, say, a game between All-Stars?

I really don’t follow baseball all that much. I don’t really like it. I see a game if I’m passing through an airport and it happens to be on. “Oh, there’s a baseball game.” It’s funny. My mind is so different. It’s not there anymore. But I don’t think they have a lot of good players, from what I see. You have a handful of good players on each team. When I played, teams were stacked. Guys coming off the bench were great. I did see the World Series last year [between the Mets and the Kansas City Royals]. Those teams couldn’t beat us. They weren’t tough enough.

I guess you’ve given up baseball but you haven’t totally given up the trash talk.

[Laughs]. No, i guess not.

What’s something you really want people to take away from this film?

I want people to take away that happiness is more important than stuff.

And you see your story as a kind of object lesson in that.

When you think of where a lot of people come from, especially African Americans, they come from dysfunctional homes without father figures. And people underestimate what they’ve been through. LeBron James — people underestimate what he’s been through just being raised by a mother. He had to learn how to be a father to himself. That’s what I had to learn. I had to learn to be a man on my own.

Most people would just see me put on a uniform and think, “Why can’t he be happy?” But I’d be hitting home runs and thinking about my father. I’d run the bases and wonder, “Why did he reject me?” People didn’t see it. But I was feeling it.

On Twitter: @ZeitchikLAT

With O.J. Simpson nominations, Emmy voters hold up a period-piece mirror

HBO’s topical crime drama ‘The Night Of’ is more of a character study than a procedural

Oscar-winner Alex Gibney looks at cyberthreats present and future in ‘Zero Days’

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.