With ‘Wadjda,’ Haifaa Mansour makes her mark in Saudi cinema

In a country where women can’t freely move around, Saudi director Haifaa Mansour covertly films the provocative story of a girl’s quest for a bicycle.

- Share via

The production lost two days to sandstorms. The crew faced a last-minute scramble when the nervous owner of a mall changed his mind about allowing filming there. Some days locals chased the cameras away; other days they brought platters of lamb and rice to the set, and asked to be extras.

Meanwhile, the director hid in a van, speaking to her cast via walkie-talkie.

In Saudi Arabia, where driving a car is a subversive act for a woman, a 39-year-old mother of two has done something remarkable: written and directed what her distributor believes is the first feature film shot entirely in the ultraconservative kingdom.

Haifaa Mansour is the director of "Wadjda," a drama about a plucky 10-year-old girl who enrolls in a Koran recitation competition in order to win money for a bicycle she's forbidden by law to ride.

Like her young protagonist, Mansour's own story is one of feminine moxie.

In a sly protest of the country's ban on women behind the wheel, she drove herself to her wedding in a golf cart. Because women in Saudi Arabia can't mingle publicly with men outside their families, she shot her movie covertly on the streets of the capital, Riyadh. With movie theaters banned, she screened "Wadjda" in two foreign embassies and a cultural center.

"Wadjda" director Haifaa Mansour shot her film entirely in Saudi Arabia, doing so covertly because women can't mingle publicly with men outside their families. (Tobias Kownatzki / Sony Pictures Classics) More photos

Petite, self-assured, wearing white high-tops and blue nail polish, Mansour is modern in both her fashion and bearing. She speaks English quickly and colloquially, dropping frequent "you knows" into conversation. And she isn't afraid to counter misperceptions about her homeland, as when she gently corrected Bill Maher for calling Mecca the Saudi capital during a recent appearance on his HBO show.

Laced with empathy and humor, "Wadjda" is a quietly provocative portrait of a culture that straddles the centuries, where men wear the ancient white thobe but carry the latest iPads and women hold important jobs as doctors and news anchors but have yet to vote in an election.

"I didn't want to make a movie about women being raped or stoned," Mansour said in an interview in Beverly Hills in June. "For me it is the everyday life, how it's hard. For me, it was hard sometimes to go to work because I cannot find transportation. Things like that build up and break a woman."

The eighth of 12 children of a poet, Mansour grew up in a small town in a home that she describes as nurturing for a little girl.

"My family is very traditional, but my parents are very supportive, very kind," she said. "I never felt I can't do things because I'm a woman."

When Mansour was a teen, her mother removed the light veil she wore while picking her daughter up from school, a gesture that mortified the young woman at the time, but empowers her when she reflects on it now.

Though movie theaters have been shuttered in Saudi Arabia for decades for religious reasons, Mansour said her father, like others, often rented VHS tapes at Blockbuster for the family to watch -- she grew up on Jackie Chan movies, Bollywood productions, Egyptian cinema and Disney animated films. "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" was a particular favorite.

Waad Mohammed, 12, stars as the plucky title character in "Wadjda," by Saudi director Haifaa Mansour. (Tobias Kownatzki / Sony Pictures Classics) More photos

"In small-town Saudi, there is nothing to do. You don't get to exercise your emotions because nothing much is happening, you know?" she said. "So to see people falling in love and fighting, it's so powerful, you see beyond your small town."

After earning her bachelor's degree in comparative literature at the American University in Cairo, she returned to Saudi Arabia but quickly felt stymied.

"Going back to Saudi as a young woman, trying to assert yourself in the workplace, you have all those ideas … and all of a sudden you realize because you are a woman you are not heard," she said. "It was such a frustrating moment in my life. It was as if you are screaming in a vacuum."

The idea of women holding jobs still unnerves some Saudi men -- writer Abdullah Mohammed Daoud recently encouraged his more than 97,000 Twitter followers to sexually harass female grocery store clerks to intimidate women from working.

Recalling the freedom she found in movies, Mansour decided to make a short film with her siblings serving as cast and crew, a thriller about a male serial killer who hides under the black abaya worn by Muslim women. Her work -- two more shorts, a documentary and a stint hosting a talk show for a Lebanese network -- focused largely on the untold stories of Saudi women.

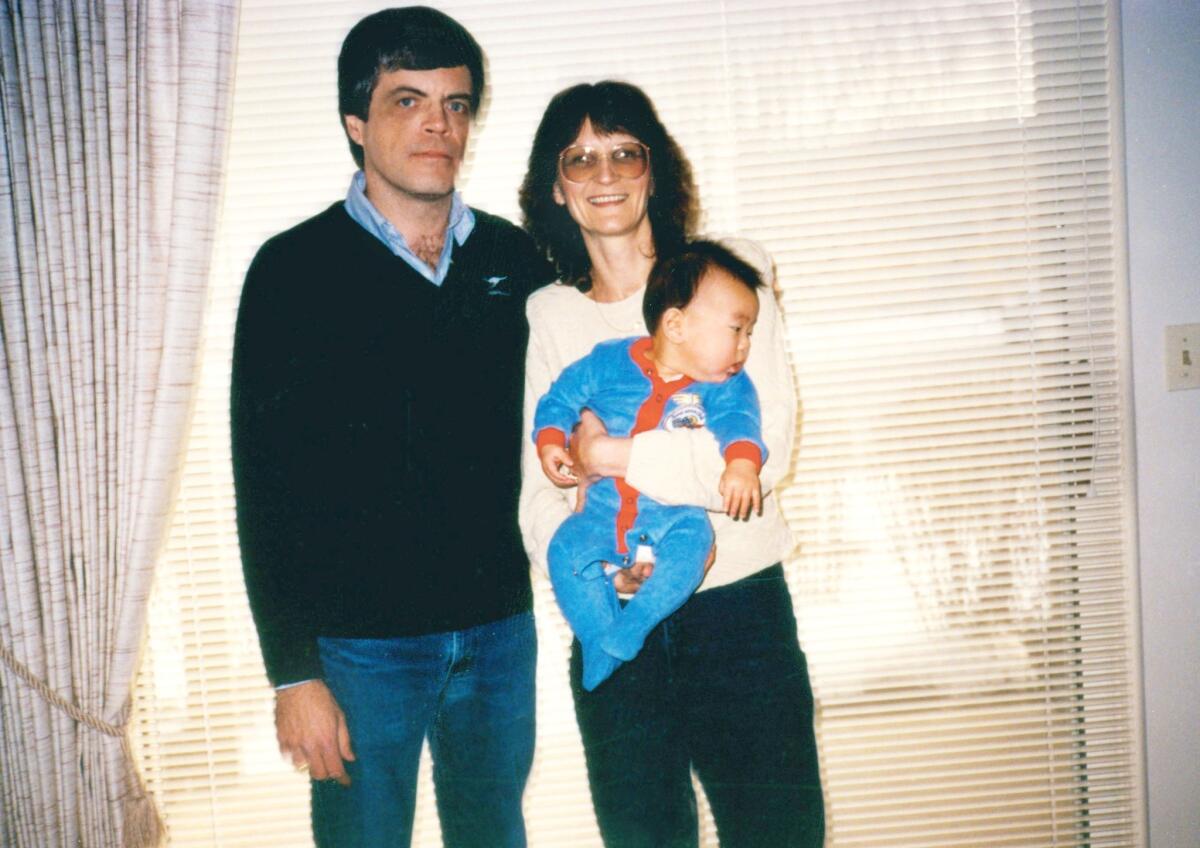

In 2005, at a U.S. embassy screening of her documentary, "Women Without Shadows," Mansour met her future husband, American diplomat Bradley Neimann. They now have two children, 2 and 5, and live in Bahrain, where Neimann works for the State Department.

When her husband was posted in Australia, Mansour pursued a master's in film studies at the University of Sydney, and wrote the script that became "Wadjda."

The story was inspired by her now teenage niece, who has tamped down her rambunctious personality to fit into Saudi norms.

"She's feisty, she has a great sense of humor, she's a hustler," Mansour said. "But my brother now is a little traditional, so she is now more what you'd expect from a Saudi girl.... I felt that is such a loss of potential."

When Mansour's script for "Wadjda" won an award at the Abu Dhabi Film Festival, it caught the eye of the co-head of the independent film group at United Talent Agency.

"I thought, 'Wow, a woman writer from Saudi Arabia won?'" Rena Ronson said. "I had to meet her. She was so open and tenacious and smart."

Over the next two years Ronson helped Mansour secure financing for her film, which cost a little less than $2.5 million. The primary obstacle, as far as many potential Middle Eastern producers were concerned, was Mansour's desire to shoot in Saudi Arabia, which she felt lent her story authenticity.

The production finally won the tacit approval of the Saudi government -- one of its backers is Rotana Group, an entertainment company primarily owned by Saudi Prince Alwaleed bin Talal. Another major financier is the German company Razor Film.

Finding actors was another hurdle. Mansour and her producers recruited child performers through small companies that hire folkloric dancers for the Eid holidays. Many of their parents were uncomfortable with a movie about empowering women.

A week before she was scheduled to start shooting, Mansour still hadn't cast her title character when 12-year-old Waad Mohammed entered the room in blue jeans, with headphones clapped over her ears. Singing along to Justin Bieber, she won over Mansour with her sweet singing voice and tomboyish style.

The movie's half-German, half-Saudi crew worked around the rhythms of Saudi life, using cellphone apps that alerted them of the five daily prayer calls. The Germans carried notebooks; the Saudis relied on oral planning.

She's very fast in overcoming new difficulties, and in an upbeat spirit."— Producer Roman Paul

On the first day of shooting, a start time of 7:20 a.m. came and went. "I don't know what we were thinking," said German producer Roman Paul. "I don't think 7:20 exists in Saudi time. We Germans learned to relax, and the Saudis learned that there is a benefit to doing things at a certain time."

Despite tension on the set -- both from disapproving observers and from the German and Saudi crews learning to work together -- Mansour was buoyant, Paul said.

"She's very fast in overcoming new difficulties, and in an upbeat spirit," Paul said.

Last summer "Wadjda" premiered at the Venice and Telluride film festivals, earning praise for Mansour's subtle direction and a U.S. release from Sony Pictures Classics, which handled the Oscar-winning 2011 Iranian drama "A Separation," about the dissolution of a marriage.

"'A Separation' was such an eye-opener to me in the sense that there were people questioning whether the film went too specific into the Iranian culture," said Michael Barker, co-president and co-founder of the Sony unit. "But if the overall story has a universal appeal, in 'Wadjda' it's about parents and kids and restrictions and freedom, that's something we can all relate to."

Sony Classics has been showing the film to noted feminists -- Gloria Steinem and Queen Noor of Jordan both attended screenings -- and will release it in the U.S. slowly over the fall, starting Sept. 13. (The movie premiered in multiple European countries this summer.)

Mansour said she plans to work in Saudi Arabia again. For her, screening her movie in the kingdom was a high.

"Film is about uplifting, embracing the love of life, it's about moving ahead, it's about victory," she said. "It's not about defeat."

One victory has already been won. This spring, a new law went into effect: With some restrictions, Saudi women are now allowed to ride bicycles.

Follow Rebecca Keegan (@thatrebecca) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

More great reads

Dodgers pitchers are quite the hit at the plate

Every time Greinke pitches, if he doesn't get any hits ... I tell him he had a bad game."

A virtual way to be with their deported friend

The more we learn about immigration, the more unfair it seems."

An adopted son discovers more than he expected

I had misjudged the magnitude of this meeting — both for my biological mother and for me."

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.