The ‘other than’ characters that give Guillermo del Toro’s ‘The Shape of Water’ its heart and power

- Share via

Guillermo del Toro’s “The Shape of Water” is, at its heart, a romance between a mute woman and, well, a fish man. But they’re not the only ones existing outside the mainstream in the lyrical, fantasy love story.

“Of all the isolated characters that might be ‘other than’ – ‘other than normal’ or ‘other than mainstream’ — mine is the most obvious because at first glance, you know I don’t belong in that environment,” says Doug Jones, with a laugh. He plays the being referred to as “The Asset” or “The Creature.”

As in “The Creature From the Black Lagoon,” a primary influence for the film. He’s a speechless, scaly, amphibian humanoid with prominent gills.

And he’s the love interest.

“That’s a very Guillermo del Toro thing. He’s said before, ‘I’ll always have a monster on my call sheets,’” says Jones, who has portrayed memorable creatures in six films for Del Toro, including “Pan’s Labyrinth,” and on TV’s “The Strain.” “He’s had a love affair with monsters, going back to his childhood. To him, monsters represent something in all of us, something that might feel out of place, unaccepted. If you really look at that monster, you can see the beauty of it, the rightness of it. Our flaws or our insecurities might be what make us really beautiful.

“In ‘Shape of Water,’ all of the isolated ones who are ‘different than’ — each finds the beauty within themselves — and what a gorgeous story to tell.”

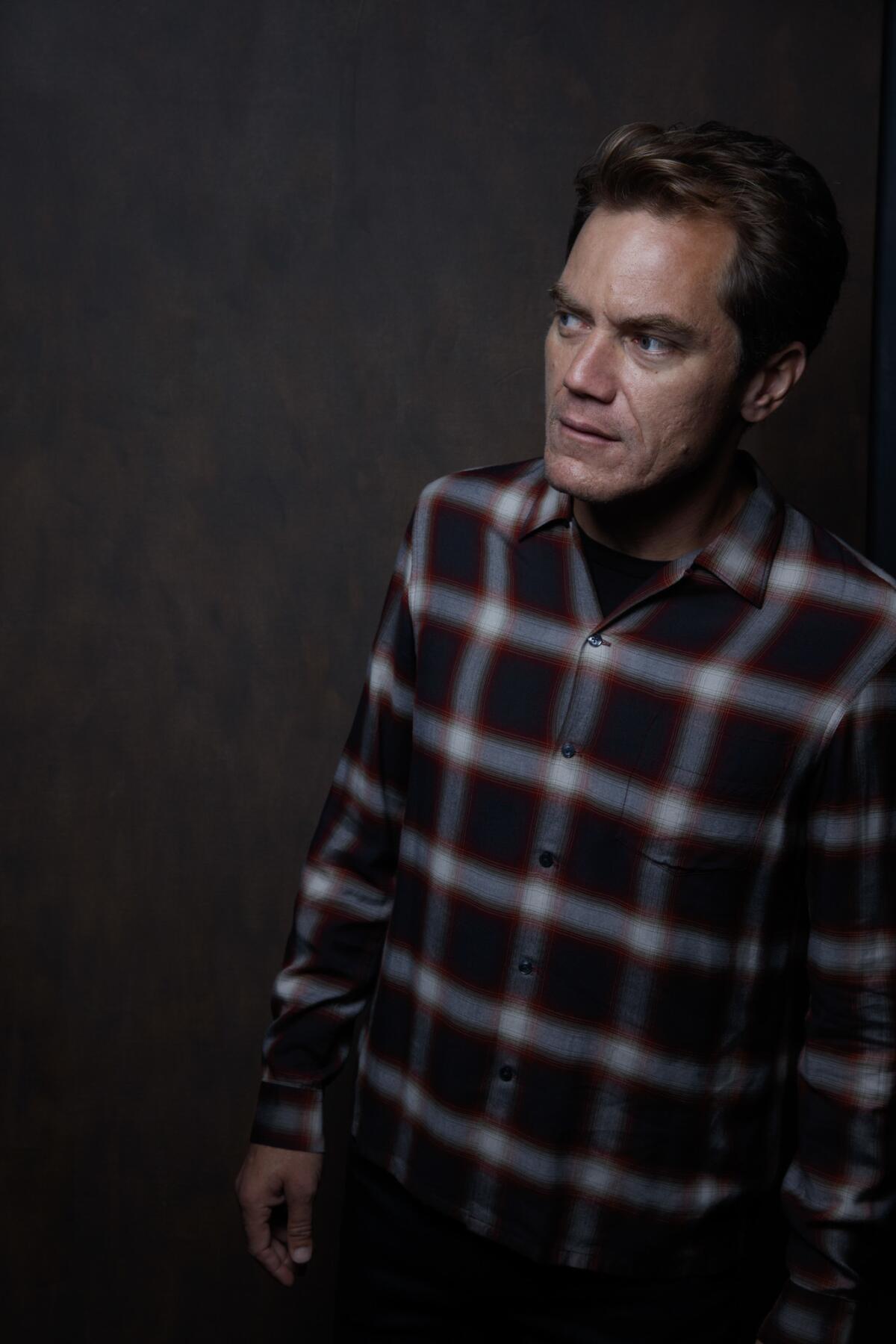

The film’s mute protagonist, Elisa, played by Sally Hawkins, works as a janitor in a mysterious lab facility in 1962 Baltimore. One day, the creature is brought in as a captive subject for study. Elisa’s neighbor is painter Giles (Richard Jenkins), who is gay; her best friend at work is Zelda (Octavia Spencer), who is an African American janitor seeking respect in a world too slowly desegregating. Even potential antagonist or ally Hoffstetler, a highly placed scientist (Michael Stuhlbarg), has secrets that alienate him. Only government agent Strickland (Michael Shannon) seems to “fit in,” and his actions are the film’s most inhumane.

Oscar nominee Jenkins says, “In 1962, if you were a straight, white man, life was great. If you weren’t, it wasn’t so good. You didn’t even talk about being gay, or gay people. You were invisible if you were an African American or you had a disability. I used to say, ‘We didn’t have any gay people in high school until our 35th reunion.’ I mean, it’s true; you had to live a lie.”

Like Jenkins, Jones remembers the era of the film from firsthand experience and describes himself as growing up socially privileged.

“I remember that era being rather glorious: ‘Things are in color now. Cars have wings on them. Kitchens are sparkling and new.’ Things were great from my perspective. I think this movie helps open up other perspectives,” says Jones, pointing out that while many characters are essentially without a voice, the protagonist literally has none.

“I was not a black woman in the ‘60s, or a gay man, or a mute woman. Now I realize, ‘Oh my gosh, there were so many different takes on that era … and the era we’re in today.’ If you want to draw parallels between yesterday and 2017 and the current political and civil situations in the world, you certainly can.”

Spencer was pleased Zelda was not defined by racist treatment in the film, which opens in New York on Dec. 1 and will be shown in other select cities starting Dec. 8.

“I’ve played women of this era before, and each time, they had to play the specifics of their circumstances — being treated as second-class citizens, having no agency and no civil rights,” says the Oscar-winning actress. “But Guillermo empowers Zelda in such a way that the only time she’s confronted by that is through the villain, Michael Shannon’s character. She doesn’t have to play to that; she’s dealing with problems within a relationship. That, to me, is refreshing.

“Those circumstances were there for me emotionally. That’s why it was easy for me to hold my tongue when speaking with Strickland. But it was wonderful not to have to address it in my narrative for the very first time.”

The scientist Hoffstetler’s very humanity puts him at odds with his colleagues and his mission. There are reasons why audiences might root against him, but he is one of the few in positions of power who appreciate the creature for what it is.

Stuhlbarg, who also appears this month in Luca Guadagnino’s “Call Me by Your Name,” finds it easy to understand why viewers’ hearts go out to unconventional characters such as his, in just the way Elisa and the creature find common ground outside the mainstream.

“I think maybe there’s a sense of relating to their situation, of them being voiceless or helpless and stuck in a hard place. They’re innocents at heart and fighting for what they know to be right.”

Even Shannon’s Strickland, the embodiment of “The Man,” is motivated by vulnerability — the fear of winding up on the “outside.”

“I think the real telling moment is when he realizes his boss is ready to throw him away at a moment’s notice the second he makes a mistake,” says the twice-Oscar-nominated actor. “I think that really recalibrates his whole mind set.”

Jones adds, “Even the kids at the cool table are terrified every day of losing their status. I think all of us have had a monster within us, or felt unlovable. I certainly did. When I was in grade school and high school: Tall, gangly, out of sorts, unathletic. Every character in this film deals with that in some form.”

Perspective as a key to empathy is part of the plan, says Jenkins:

“If you see this movie and you root for Sally and the Creature to get together; if you root for Giles, if the fact that he [endures a romantic reversal] is painful for you, you’ve walked in these people’s shoes and you’ve empathized with them. Maybe it will help you understand the lives people like this have had to lead, and it’ll open your heart up a little bit. I know that’s Guillermo’s wish.”

Del Toro has expressed his aim “to create a beautiful, elegant story about hope and redemption as an antidote to the cynicism of our times … To me, this is a time when America stopped — it’s a time of racism, of inequality, of people thinking about the brink of nuclear war. In a few months, [President John F.] Kennedy will be assassinated. So in a way, it’s a horrible time for love, yet love happens.”

Stuhlbarg agrees. “It’s a love that’s trying to thrive in an environment that’s almost impossible,” he says. “With all the difficult news we get daily … to tell stories that have some optimism of people being able to find each other in the chaos of the lives we live, has tremendous relevance to today.”

Spencer, a committed political activist, says, “I’m a woman of color. I know what it’s like to be ‘the other.’ I live it every day. And given the current political climate, anyone existing as the other knows what it’s like for these characters. That’s why it appeals to people on so many levels.

“There’s this sociopolitical side, there’s a side for those who are cinephiles and artists, and there’s a side for those who are hopeless romantics.”

Shannon acknowledges the film’s themes, but says they swim beneath a “seductive” surface crafted by someone he calls a cinematic “master”: “Rather than this film being a polemic or pedantic, it’s an oasis from the ugliness and nastiness that seems to be pervasive during this time. I think it’s a very seductive film, aurally, the colors, the textures, you can’t take your eyes off it.

“I’m not sure the movie can solve anybody’s problems or make your breakfast in the morning, but it’s so damn beautiful.”

ALSO

Guillermo del Toro's 'The Shape of Water' is a genre-blending movie about loving 'otherness'

For Octavia Spencer, moving past race to play a 'regular woman' in 'Shape of Water' was refreshing

Guillermo del Toro's 'The Shape of Water' pretty much guaranteed the TIFF audience award

TV horror vs. movie horror: Guillermo del Toro on telling scary stories across different mediums

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.