‘Ash Is Purest White’ director Jia Zhangke on the film that changed his life

- Share via

“Ash Is Purest White” director Jia Zhangke had an art career ahead of him until a film changed his life.

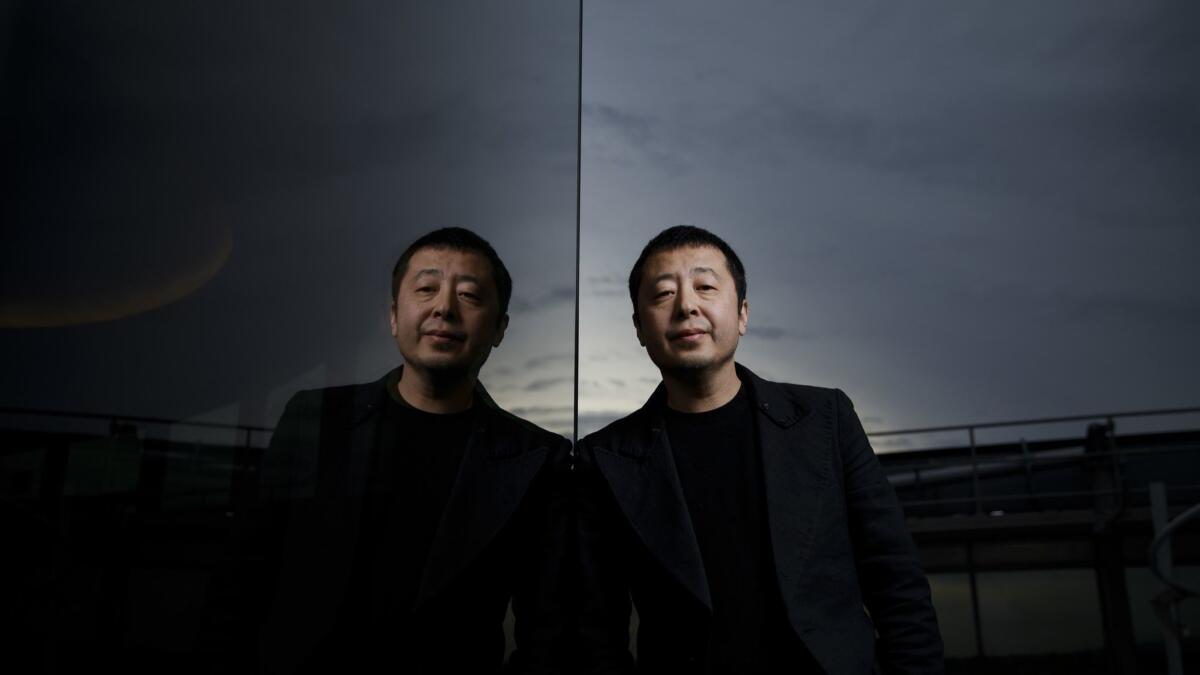

“In 1991, I was 21, studying to be an artist,” he says during a recent interview, speaking in Mandarin. A small, boyishly faced man dressed in fashionable black, he speaks slowly in a calm, deliberate way. “I happened to see ‘Yellow Earth’ in a theater. When I came out, I thought, ‘This is what I should be doing.’”

“Yellow Earth” was the debut feature of Chen Kaige, a leading member of China’s legendary “Fifth Generation.” These directors emerged in the 1980s, graduates of the Beijing Film Academy, which at that time was the only film school in China. They emphasized stories that were personal and truthful to their own experience, conveyed with distinct cinematic flourishes. Shown at the Hong Kong International Film Festival in 1985, “Yellow Earth” sent a shockwave through cineastes — here, finally, was a real departure from the schlocky propaganda features of the Maoist era and a window into modern China.

The film also sent a shockwave through Jia. “Within the first 10 minutes or so, I started crying,” he says. “Actually, it’s not such a sad film, and it was about 1930s China, not even our era. But it took place in the region of the Yellow Earth, my own hometown. I’d never seen it depicted in film. And that kind of poverty, I knew that poverty. So I realized that my own life could be the stuff of the screen.”

More than 25 years after he saw “Yellow Earth,” Jia is considered by many to be the leading filmmaker of his own generation, sometimes called the “Sixth Generation,” and his latest movie, “Ash Is Purest White,” was one of the most talked-about pictures at last year’s Cannes Film Festival. Jia is known for his languid, even elliptical, storytelling that often mixes narrative with documentary footage. “Ash Is Purest White,” which opened in the U.S. on Friday, is at once gangster drama, romantic tragedy and wistful observation of a rapidly changing China.

When asked about how the Chinese gang seems to mirror Hong Kong triads in dress and rituals, Jia says, “They got all that from watching Hong Kong gangster films.” He’s even inserted Cantopop star Sally Yeh’s song from John Woo’s “The Killers” (1989) into the film.

Jia watched plenty of Hong Kong gangster movies after he changed course from his art career and applied to the Beijing Film Academy. But he also watched foreign pictures denied to ordinary citizens in China thanks to his major in film theory, which enabled him to see almost everything.

Jia made shorts while at the academy, then scrounged up enough money to make his first three features, all done outside the government system, and all based in his home province, Shanxi. As a budding auteur, he wrote his own scripts, often employed amateurs and shot on location.

His first feature, “Xiao Wu” (1998), the story of a pickpocket, was shown at the Berlin International Film Festival. His third, “Still Life” (2006), about a man and a woman searching for their spouses in a town about to be destroyed during construction of the Three Gorges Dam, won the Golden Lion in Venice.

REVIEW: Jia Zhangke’s ‘Ash Is Purest White’ is a deeply moving gangster love story »

He first collaborated with Zhao Tao, a dancer turned actress, in his second film, “Platform” (2000), about the lives and interactions of a theater troupe in the 1980s. In it, he showed China’s sociopolitical changes through popular music and fashion — two of the young men don bell bottoms with relish as they and their friends try awkwardly to dance to rock ’n’ roll. Jia also shot on and around the ancient city walls of Fenyang, the thick barriers that kept the world out and its inhabitants in.

Zhao became his muse and wife, and she was featured in his next films. In “Ash,” she plays the lead character of Qiao, a mobster’s girlfriend. The role showcases her talent for handling shifting nuances of comedy and tragedy. Qiao is happily in love with Bin (Liao Fan), head of a local criminal gang, but their lives are upended after they’re arrested and she gets five years in prison. Despite Bin never coming to visit her (he got off with two years), she goes and looks for him on her release, which leads to some unhappy revelations.

How is it for Jia to work so closely and so frequently with Zhao?

“When I set about writing, ‘I think, “No she can’t be in this next film,”’” he says. “But when I finish, I know she has to be in it. First, she’s a northerner, she understands that kind of character, she can empathize. She can also bring moments of surprise.” He doesn’t let her read the script until it is completed. When she does get to read it, he says, “She often has lots of suggestions, especially from a woman’s point of view.”

Jia tends to work with Chinese actors mostly known to mainland audiences and with amateurs. One exception is Joan Chen, who was featured in “24 City” (2008), a quasi-documentary about the end of the factory era that took care of workers from cradle to grave. It zeroed in on the lives and memories of three generations of factory workers in Chengdu. In an inspired stroke of casting, Chen was asked to play a worker who was popularly known as Xiao Hua, the role that brought her to fame in China before she restarted her career in the United States (and was cast to play the Empress in Bernardo Bertolucci’s “The Last Emperor”).

She took the small part “because I’ve always loved his films,” Chen says in a phone interview. “‘Xiao Wu’ was in Berlin when ‘Xiu Xiu: The Sent-Down Girl’ [her own directorial debut] was there. I feel his films convey very real representations of China’s changes, of the displacement of people.”

To prepare for her role, she went to the location and met with former workers. “He didn’t want to rehearse, because he wanted me to have a little awkwardness,” Chen says. She recalls that they did only two takes. “He’s pretty sure-footed; he doesn’t have to do lots of takes. To do what he does, everything needs to be economical. He writes his own scripts, and he started with small budgets.”

The inspiration for “Ash” came from reviewing old footage from the early 2000s, when Jia got his own mini-digital video camera and would shoot slice-of-life footage wherever he went. The new film begins with a bus ride where we look into the weary faces of the passengers, then focus on a young girl. At first, she’s fast asleep, then she opens her eyes and looks right into the camera. It’s a moment of self-consciousness that’s a precursor to the self-consciousness the main characters in the film experience.

The Chinese title for the movie is “Sons and Daughters of the Jianghu” — “jianghu” is a term that literally means rivers and lakes, but refers to marginal, even mythic, realms. Ancient martial arts heroes and villains live in the jianghu, as do modern gangsters.

“I’ve long been observing the changes happening in Chinese society,” the director says. “The biggest changes are in people, now so obsessed with money and advantages. The old ways of relating to one another has changed. So I thought looking at the changes from the point of view of the jianghu would be especially interesting.”

His first three films were made outside the system and were banned in China. The first movie he made legally was “The World” (2004), about a young woman (Zhao) working in a Beijing theme park featuring miniatures of world-famous sights, like the Eiffel Tower, London Bridge and the skyscrapers of Lower Manhattan. That time, he obtained the necessary government permits and censorship review, which were essential for getting his pictures shown in Chinese theaters. When asked whether “Ash” passed censorship, despite its depiction of mob life, Jia says it did, without a cut, then adds with a smile, though perhaps with some friendly persuasion. It was released in China in September and broke his personal box office record on its opening weekend.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.