Aretha Franklin, who defined an era as the Queen of Soul, dies at 76

Aretha Franklin talks about her hit song “Respect” and her love of music in a 2008 interview.

- Share via

Aretha Franklin, the preacher’s daughter who became the “Queen of Soul” and forged the template of the larger-than-life pop diva with her exuberant, gospel-rooted singing, has died. She was 76.

Franklin died Thursday of advanced pancreatic cancer, according to her publicist Gwendolyn Quinn.

For the record:

3:00 p.m. Aug. 17, 2018This article misstates Aretha Franklin’s age when she gave birth to her sons Clarence and Eddie. Clarence was born when she was 12, not 14. Eddie was born when she was 14, the same year she recorded an album of hymns for the JVB gospel label, not three years after recording the album.

In a career she began as a teenager in the 1950s, Franklin went from singing in her father’s Detroit Baptist church to performing for presidents and royalty as she took soul music to its creative and commercial pinnacle.

Her unfettered singing inspired an uninterrupted line of female singers, from Gladys Knight and Patti LaBelle in the ’60s and ’70s to Whitney Houston and Mariah Carey in the ’80s and ’90s and Beyoncé and Rihanna in the ’00s.

“Christina Aguilera, Pink … they all want to shout their heads off,” author David Ritz, who co-wrote Franklin’s 1999 autobiography, “Aretha: From These Roots,” told The Times. “She was the first one to do that.”

Remembering Aretha Franklin: Complete coverage »

When Franklin’s clarion voice hit the airwaves in 1967, she seemed a force of nature, a voice with the force of a horn section that claimed full attention, whether lamenting love gone wrong or demanding “ree-ree-ree-ree-spect.”

“Aretha shattered the atmosphere, the esthetic atmosphere,” author and critic Peter Guralnick said in a 1987 interview. “She set a new standard which, in some way, no one else could achieve. … You had a number of gospel singers who were filled with the spirit. She translated that spirit into the secular field. ... She translated that feel and that fire.”

Franklin’s impact transcended radio playlists, record charts and even musical matters. Many saw her as an embodiment of an upsurge in African American and female pride. Her 1967 signature hit “Respect” became an anthem of empowerment that resonated across gender, race and class divisions.

“So many people identified with and related to ‘Respect,’” Franklin wrote in her autobiography. “It was the need of a nation, the need of the average man and woman in the street, the businessman, the mother, the fireman, the teacher. Everyone wanted respect. It was also one of the battle cries of the civil rights movement.”

The song — originally recorded by its writer, Otis Redding — helped define Franklin as a role model for an emerging demographic.

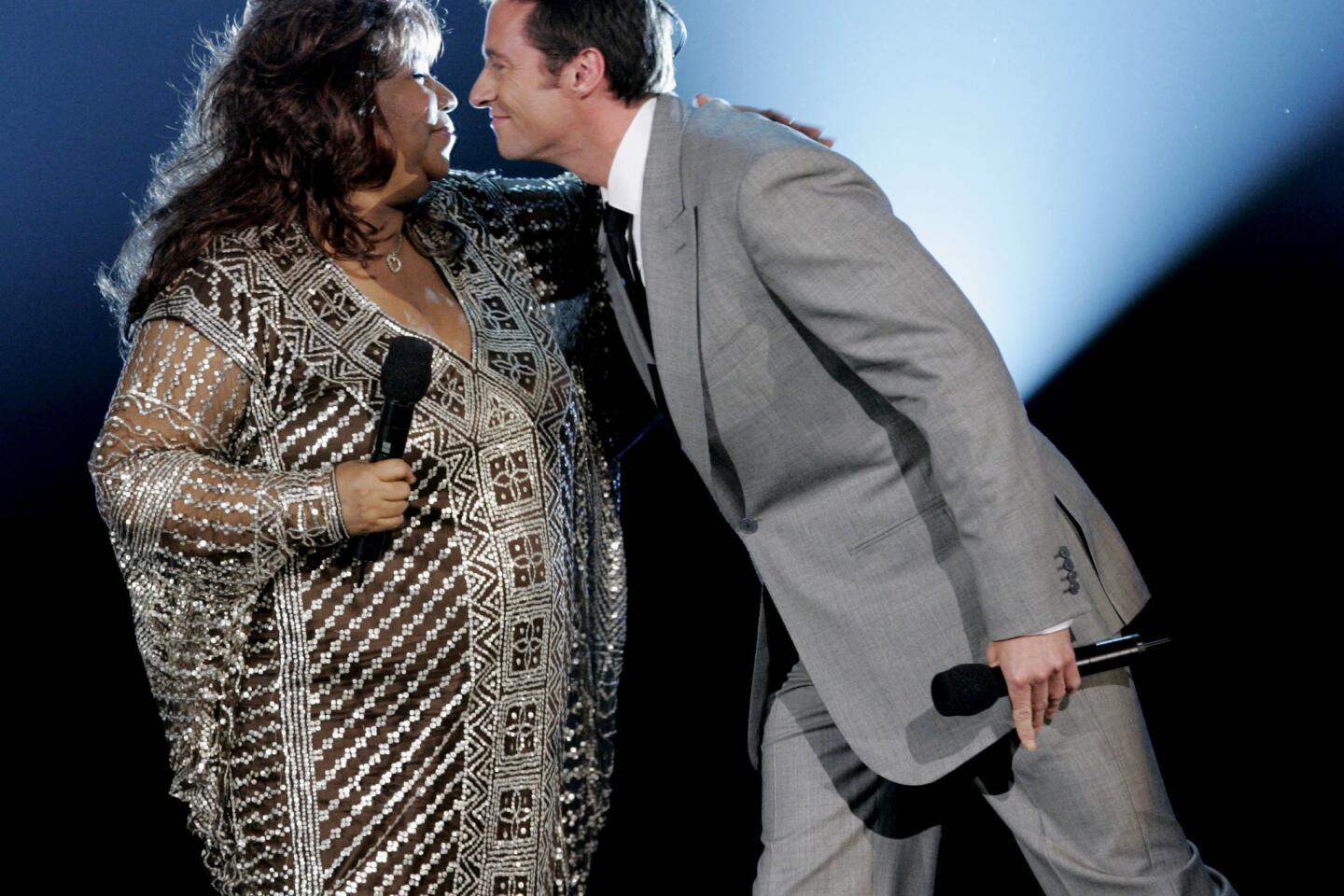

Though she reigned over soul music, Franklin tackled a variety of genres, including pop standards, show tunes and jazz, early in her career. One of her biggest moments came at the 1998 Grammy Awards, where she filled in at the last minute for the ailing Luciano Pavarotti and sang a show-stopping rendition of Puccini’s aria “Nessun Dorma.”

Her career became more sporadic following her late-’60s domination, but she returned periodically with hits, high-profile appearances and an array of decorations.

She was the first woman inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, in 1987. Other honors include the National Medal of Arts, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the NAACP Vanguard Award and the Kennedy Center Honors. She won 18 Grammys as well as lifetime achievement and legend awards from the Recording Academy.

She graced the cover of Time magazine in 1968 and saw the Joffrey Ballet choreograph a program based on her music. She sang at the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s funeral and at the inaugural celebrations of Presidents Carter, Clinton and Obama.

Yet Franklin remained an unusually private star, keeping a veil over a turbulent private life that included her parents’ divorce, her mother’s death, teenage motherhood, stormy relationships with men, the slaying of her father, financial problems and struggles with weight and smoking.

She disputed her public image as difficult and reclusive, writing in her autobiography, “I am Aretha, upbeat, straight-ahead, and not to be worn out by men and left singing the blues.”

But some who knew her saw it differently.

Jerry Wexler, the influential Atlantic Records producer, wrote in his 1994 memoir, “Rhythm & the Blues: A Life in American Music,” that he thought of Franklin as “Our Lady of Mysterious Sorrows.”

“Her eyes are incredible, luminous eyes covering inexplicable pain. Her depressions could be as deep as the dark sea,” he wrote. “I don’t pretend to know the sources of her anguish, but anguish surrounds Aretha as surely as the glory of her musical aura.”

Aretha Louise Franklin was born March 25, 1942, in Memphis, the fourth of Barbara and Clarence LaVaughn Franklin’s five children. Her parents, who both came from Mississippi and moved together to Memphis, relocated to Buffalo, N.Y., and then to Detroit when Aretha was 2.

C.L. Franklin was a gifted rhetorician and singer, and he prospered as the pastor of the New Bethel Baptist Church. He provided his family with a comfortable home where house guests included musical luminaries Art Tatum, Nat King Cole, Dinah Washington and gospel great Clara Ward.

Barbara and C.L.’s marriage ended when Aretha was 6, a parting widely characterized as a mother deserting her family. Aretha has disputed that account and said that her mother continued to visit, call and host her children in her new home in Buffalo.

Music was in the air in the Franklins’ North End Detroit neighborhood, which produced such musical stars as Smokey Robinson (a lifelong friend of the Franklins), Diana Ross, Jackie Wilson and members of the Four Tops. Aretha took to the piano when she was 8 and soon could play tunes she heard on the radio by ear.

She and her sisters Erma and Carolyn sang together at New Bethel, and Aretha received some schooling from James Cleveland, who would later find gospel stardom and a loyal congregation in Los Angeles. She was performing solos in the church at age 10.

Her father’s recorded sermons were being released on Chess Records’ Checker label, and, as his fame grew, he made appearances in churches around the country. Aretha would open for him with some songs at the piano, then would punctuate his orations with instrumental adornments, developing the impassioned musical gestures that would mark her music later in her life.

She recorded her own album of hymns for the JVB gospel label when she was 14, and the same year she gave birth to a son. She didn’t identify his father, nor did she name the father of her second son, Eddie, when he was born three years later.

At the end of the 1950s, Aretha saw her friend Sam Cooke move from gospel prominence to pop success. Her father encouraged her decision to start a secular career, and rather than join some of her friends at the new local label, Motown, she set her sights on a large, international company.

She recorded a demo that impressed Columbia Records’ famed talent scout and producer John Hammond, who had discovered and/or developed Count Basie, Benny Goodman and Billie Holiday, among others. Franklin moved to New York and signed with the label in 1960.

Hammond produced her first two albums the same year, a mix of jazz-flavored standards and blues. Like much of her work for the label during her seven years there, it included some strong moments but suggested that Columbia wasn’t sure how to tap her full potential.

As Aretha took “finishing” classes and dance lessons and toured clubs as an opening act for comedians and jazz combos, Columbia paired her with various arrangers and producers, but all they had to show for it were some R&B chart entries and one top 40 record, “Rock-a-bye Your Baby With a Dixie Melody.”

When Wexler, who co-owned Atlantic Records, heard in 1966 that Franklin’s Columbia contract was over, he made contact and signed her to the company that she’d had her eye on.

The New York-based independent had become the capital of R&B with Big Joe Turner, Ray Charles and Ruth Brown in the 1950s, and in the 1960s it was riding high with the soul music of Solomon Burke, Wilson Pickett and, through its Stax affiliate, Otis Redding and the duo Sam and Dave.

Wexler planned to let Stax’s Memphis soul machine handle Franklin, but when the label demurred, Wexler took her to the Fame Studios in Muscle Shoals, Ala., to record with the band of young, blues-loving white musicians who had played on hits by Percy Sledge, the Staple Singers and Arthur Conley.

Their first session yielded a finished “I Never Loved a Man (The Way I Love You)” in a mere two hours, and the age of Aretha had begun.

Wexler, his assistant and arranger Arif Mardin and engineer Tom Dowd were formally in charge of subsequent recordings in Atlantic’s New York studio, but their smartest move was, as Wexler put it, to urge “Aretha to be Aretha.”

Franklin had learned something about making records while with Columbia, and she acted as the prime mover in the classic tracks they were recording.

“It was an amazing process,” Mardin told Billboard magazine in 2003. “She’d come to the sessions all prepared. She’d start playing the song on the piano. I’d write down the chord sequence; the bass player would look at her left hand and copy her bass figures. The guitar players would do the same by observing her right hand. … The background singers’ parts would also be worked on in the studio or back room, Aretha having given them their parts.”

Much later, Franklin would complain, rightly, that she should have received co-producer credit, a title she was awarded near the end of her Atlantic years. But in 1967, things were moving too fast to worry about it. Franklin was fulfilling the gospel-R&B fusion pioneered by Ray Charles and turning soul music’s tentative courtship of the mainstream into a rout.

“I Never Loved a Man” topped the R&B chart and made the pop top 10 early in 1967 and was followed by four more top 10 singles, peaking with the No. 1 “Respect.”

Franklin and her sister Carolyn had worked out a version of the song, a 1965 R&B hit for Redding. In the studio, Wexler borrowed a bridge from Sam and Dave’s “When Something Is Wrong With My Baby,” while Aretha and her backup singing sisters Carolyn and Erma came up with the “sock it to me” refrain, transforming the “street cliché” from their Detroit neighborhood into a national catchphrase.

It was neither my intention nor my plan, but some were saying that in my voice they heard the sound of confidence and self-assurance.

— Aretha Franklin

“That little girl done took my song away from me,” Redding reportedly said when Wexler played him the new version.

More than a provider of catchy entertainment, Franklin found herself being held up as a symbol.

“It was neither my intention nor my plan, but some were saying that in my voice they heard the sound of confidence and self-assurance,” she wrote in her autobiography. “They heard the proud history of a people who had been struggling for centuries. I took these compliments to heart and felt deeply humbled and honored by them.”

Her albums were big sellers, and Franklin was the toast of the pop world. She continued her streak with “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman,” written by Gerry Goffin and Carole King.

Eric Clapton played on her third album, and though the hits became less frequent later in the decade, Franklin was full of surprises, recording songs from outside the R&B field such as the Band’s “The Weight” and the Beatles’ “Eleanor Rigby.”

She stayed with Atlantic through the difficult decade of the ’70s, and though her last pop hit for the label came in 1973, she did notable work throughout her tenure.

Perhaps most important was her 1972 album, “Amazing Grace.” It was an acclaimed and bestselling return to gospel, recorded live in Watts with her old mentor James Cleveland.

The album went double platinum and featured voices from across South Los Angeles. Its success, said Tyree Boyd-Pates, history curator of the California African American Museum, “changed gospel music” in Los Angeles. “The ordinary African Americans in South Los Angeles were participants in one of the highest moments in gospel music — and it happened in our backyard.”

Another live album, “Live at the Fillmore West,” captured her dynamism and featured a duet with Ray Charles on “Spirit in the Dark.” She worked with such distinguished producers as Quincy Jones and Curtis Mayfield and moved away from pure Southern soul toward the evolving funk style.

Her eclecticism has been criticized as uncertainty, but Franklin often said she was drawn to many forms of music, and her approach to her career suggested a desire to compete with mainstream stars such as Diana Ross and Barbra Streisand.

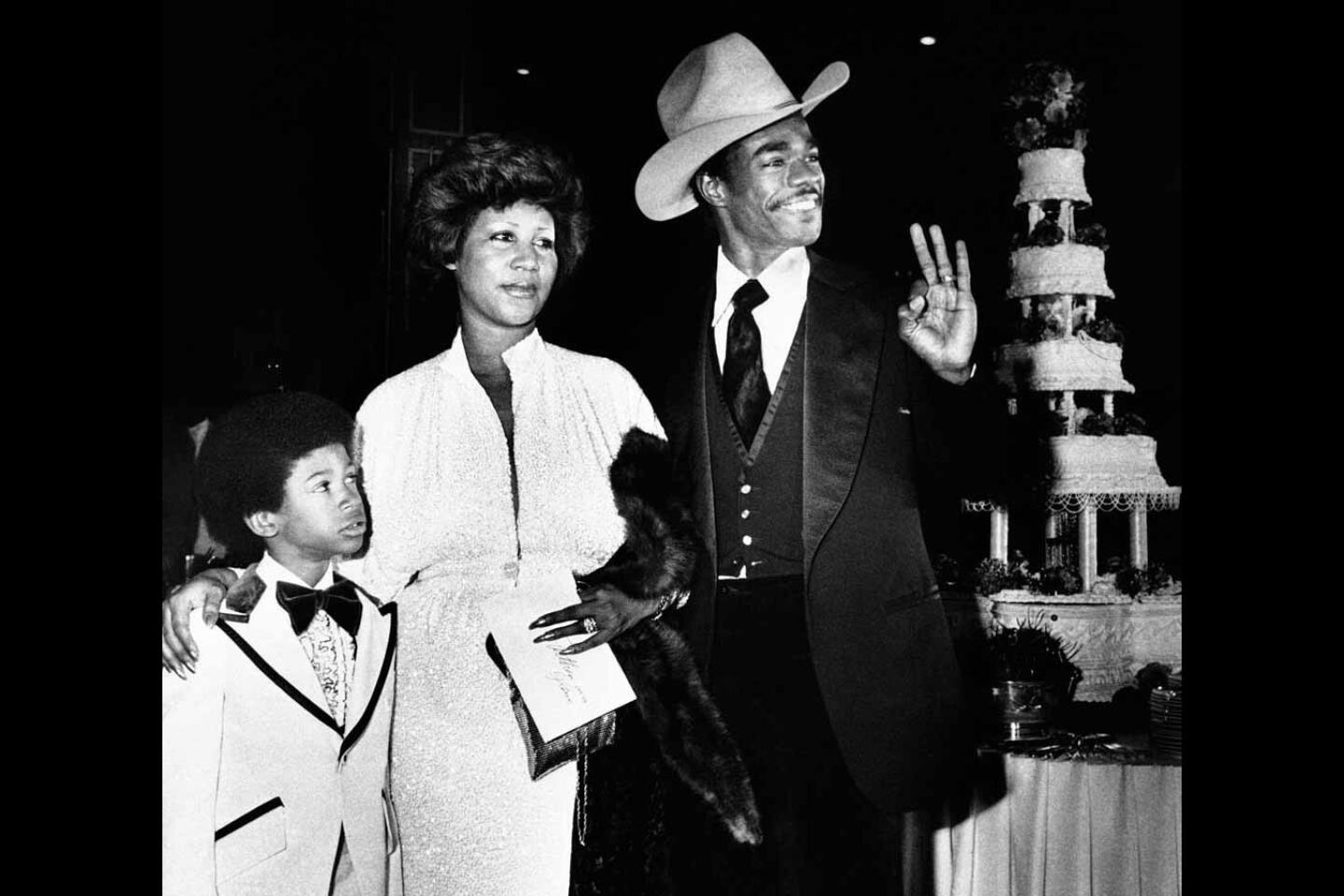

Franklin moved to Encino in 1970. Her eight-year marriage to her manager Ted White (who reportedly had once struck her in public) was over, and she was in a relationship with businessman Ken Cunningham, her former road manager, with whom she had a son, Kecalf, in 1970.

Like many established singers, she struggled to find a niche in the decade’s disco boom, and her health suffered from a two-pack-a-day smoking habit and a fondness for fast food that led to weight gain. At one point, she had to borrow money from her father to make ends meet.

In 1979, C.L. Franklin was shot in his home by burglars and lapsed into a coma that lasted until his death in 1984.

As she was negotiating the financially and emotionally stressful process of traveling between Los Angeles and Detroit to care for her father, her Atlantic contract ended and she signed with Arista Records, whose chief, Clive Davis, had shown a flair for pairing singers with material and collaborators.

That meant Franklin was now at the mercy of her producers rather than being the musical driving force, but she returned to the charts with her work with Luther Vandross, who produced “Jump to It” in 1982, and Narada Michael Walden, who oversaw “Who’s Zoomin’ Who” and “Freeway of Love” three years later.

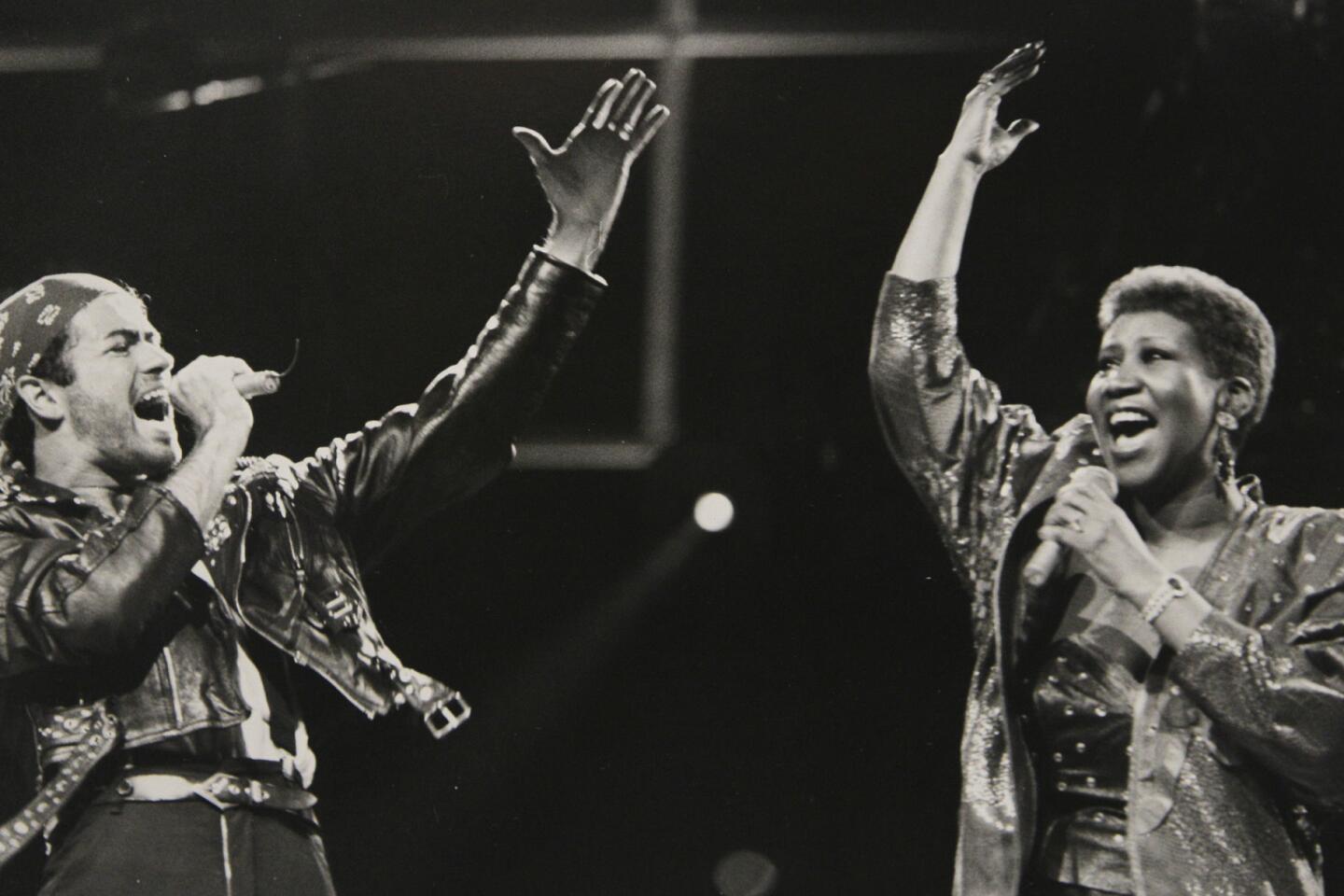

“I Knew You Were Waiting (for Me),” a duet with George Michael, was a No. 1 hit in 1987, and collaborations with Elton John, the Eurythmics and the Rolling Stones’ Keith Richards and Ron Wood continued her notable string of work with English pop and rock artists.

She moved back to Detroit in 1982, following the end of a four-year marriage to actor Glynn Turman, and did most of her subsequent recording there.

In 1983, Franklin developed a fear of flying, which limited her appearances and led to her paying damages when she backed out of a Broadway musical about Mahalia Jackson. Late in the decade and into the ’90s, she was the subject of lawsuits over nonpayment of bills, and liens by the Internal Revenue Service and the Michigan state treasury.

News stories at the time quoted associates saying that the problems stemmed from poor business management, possibly a product of her reluctance to trust outsiders. News reports on the situation also revealed that her oldest son, Clarence, suffered from chronic paranoid schizophrenia and was living in an adult foster home.

The end of the ’80s also brought the deaths of her sister Carolyn, from breast cancer, and her brother Cecil, from lung cancer.

Aretha quit smoking in 1991 and continued recording for Arista, finding some modest chart success in the mid-’90s with “Willing to Forgive” and “A Rose Is Still a Rose.” In 2014, she released “Aretha Franklin Sings the Great Diva Classics,” covering songs by Adele, Etta James and Barbra Streisand.

In early 2017, Franklin announced it would be her final year of performing, though she said she’d continue to record.

Times staff writer Randall Roberts contributed to this report.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.