Great Read: Artist Lydia Emily faces down death to spread her light

Artist Lydia Emily puts the finishing touches on her latest mural.

- Share via

Lydia Emily has an agenda: to spread tolerance, like a virus, before she dies.

The street artist, activist and mother of two has secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. (“The bad kind,” she says.) So on good days, when her hands are nimble and her eyesight is intact, Emily paints — with a vengeance.

See more of Entertainment’s top stories on Facebook >>

On a recent afternoon, however, Emily is savoring the moment, kicking back on the sun-faded patio of the Lyric Café in Silver Lake and sipping a chai latte. The L.A. native has flown in from Austin, Texas, where she lives now, to paint a mural supporting democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders on the side of the café.

Squinting into the sunlight, she looks like a cross between Patricia Arquette in the film “True Romance” and the Swiss Miss girl: platinum blond braids and short bangs, gleaming white teeth and hot red lipstick that perfectly matches her fitted button-down red shirt, and vintage black eyeglasses studded with rhinestones. Tattoos plaster her arms and back — the names of her daughters, Dorothy and Coco, as well as flowers and dice, and the Hot Rod cartoon character Rat Fink.

A Great Dane passes by, poking his nose over her lap. “Oh, hello, gorgeous!” she squeals, feeding him bits of her veggie sandwich. “I love you. Mwah, mwah, mwah,” she says, blowing him kisses.

You’d never guess that Emily is in pain. Her joints ache, her hands and feet are tingling, and it feels like red ants are biting her gums and eyeballs. By late afternoon she’ll probably have to lie down in the back of her car and rest.

For now, however, she’s gearing up to begin outlining the mural. The Sanders campaign is aware of the work, she says — they would later thank her for the mural on Facebook — but it’s not a commission. Emily is painting the mural for free with permission from the café’s building owner.

“I know my time is short,” says the 44-year-old, who uses a cane covered in graffiti art stickers and occasionally ties her paintbrushes to her fingers with shoelaces so she can more easily hold them. “So my work is about: What can I do in that time, how can I help? What kind of example can I be for my girls? I can’t sing, I can’t write, but I can paint. This is something I can do.”

::

Politically-minded works, particularly those promoting issues of social justice, are Emily’s hallmark — in her oil paintings and street art alike. Her murals are pointedly message-driven, with simplistic designs so passersby can digest them in seconds.

The new red-white-and-blue Sanders work features a jagged, sketch-like outline of the politician’s profile with “Feel The Bern” below it. She painted a similar one on 3rd and Main in downtown L.A. It was recently defaced — often the fate of public artwork —- but restored by a friend a few days later.

“I have a personal stake in his campaign,” Emily says. “If the Democrats don’t win this, I die — because I could lose my healthcare.”

Emily feels an even greater stake in illuminating issues affecting other people’s lives. Her artwork — which has appeared in the Museum of Latin American Art as well as in galleries internationally, including in Milan and Berlin — has given voice to oppressed and underserved communities. In 2012, she formed the Karma Underground, a group that raises money for other charities and has been especially focused on educating girls in rural Tibet.

Even her oil portraits of political figures, such as President Obama or former Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, feature a call to action: Every painting is created on epoxy-coated collages of the Sunday New York Times to encourage viewers to question her subjects’ back stories and their news sources. For every painting Emily sells, she donates one; for every mural commission, she paints one, pro bono, in an impoverished area.

“Political and charitable work, that’s what I do. It’s who I am,” Emily says.

Her altruism and empathy grew out a life studded with tragedies. When she was 6, Emily was molested by a family friend, she says; in her 20s, while living in Austin, she was pulled behind a liquor store and raped by a stranger. Her 13-year-old daughter, Coco, is severely autistic, and at 39, as a single mother, Emily was diagnosed with cervical cancer — all before learning she had MS about two years later.

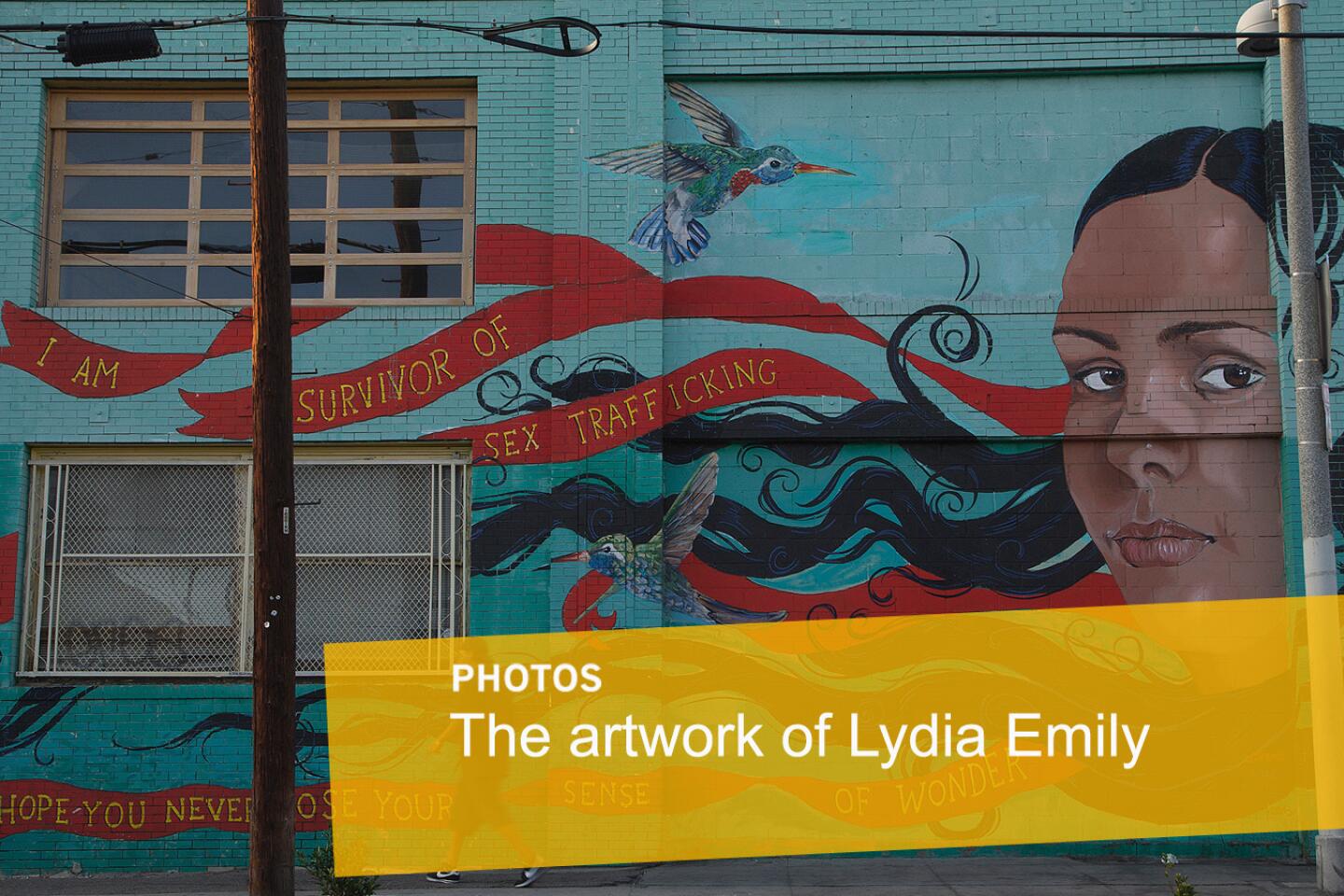

As a result, health and women’s issues are close to Emily’s heart. Her sex-trafficking mural, “Jessica’s Story,” commissioned in 2013 by Gucci’s Chime for Change charity, adorns a skid row wall in downtown L.A. She’s painted MS Society-commissioned murals in four U.S. cities, including L.A., all carrying the phrase, “There is always hope.”

Positivity is Emily’s default stance. About raising Coco, who requires 24-hour care, she says: “She’s perfect the way she is.” Looking back on her rape: “It added to my ability to see behind my head now when I walk, to guard and protect my children better, it made me the strong person I am.” Of her MS: “It’s a gift; I would think time is limitless if I wasn’t sick. I savor everything now.”

“All these horrible things have happened to her and she’s still standing and so resilient,” says writer-director Libby Spears, who’s making a feature-length documentary about Emily, called “PC594.” “The way she takes suffering to a place of light — that’s what resonates the most for me.”

::

Activism came long before art in Emily’s life — her mother was a civil rights activist (and later a stand-up comic) and her father an organic chemist. Born Lydia Emily Archibald, she, her four siblings and her “hippie trustafarian parents” lived a nomadic lifestyle in her early years, ping-ponging between countries, including Mexico and an emu farm in New Zealand.

Muralist Lydia Emily on her creative process.

They eventually settled in Ojai, and a few years later moved to L.A. “My whole life my mom was about ‘what are you doing to participate?’ It influenced me.”

Playing in punk rock bands in Austin and New York in her 20s, Emily developed an interest in art while designing album covers. Back then, she says, her political portraits were too controversial for the established gallery scene. “No one wanted Hamid Karzai hanging in their living room,” she jokes about the former president of Afghanistan.

Instead, Emily took to the streets to hang posters of her work. She learned how to wheat paste, a popular street art technique, and eventually started painting directly on concrete walls.

Join the conversation on Facebook >>

During that time, the mid-2000s, Emily — then a divorced single mother in Pasadena — lived a dual life. By day, Emily attended PTA meetings and carpooled her kids around; by night, she ventured into the streets to paint. Her roommate at the time worked as a 911 operator, she says, and would help her steer clear of the cops.

Working as a woman in the traditionally male-dominated world of street art, often painting alone, didn’t faze Emily.

“I made my own way in this community, and I don’t find it to be one where they keep women down,” she says. “Instead of complaining about how few woman there are in the street art world, just go out and paint!”

The one gender issue for women, she says, is the danger of being mugged or raped on the streets late at night. “But that’s an issue anywhere,” she says. “I’m not afraid enough to stop.”

::

For Emily, 2012 was a particularly prolific year of making street art. So she wasn’t concerned about the pain in her hands and feet; she figured she’d simply strained her extremities and needed rest. Then, one day, half of her tongue went numb. Hours of hospital tests revealed she had MS.

“That was the first time my kids heard the word ‘incurable,’” Emily says. “I’d had cancer and I’d gotten fixed; but when I had to explain what progressive MS was, that was unbearable. But we’ve moved into the teasing phase now. We joke about it. Everything’s gotta be funny. Life is too tragic if you don’t laugh about it.”

Emily met the love of her life, Andy Walthall, on a blind date last year and they were married earlier this year in an intimate ceremony on the beach in Northern California.

Although her doctors haven’t put a timeline on her illness, she says that when the time comes and her health vastly deteriorates, she and Walthall have a suicide plan for her.

“If I can’t talk and I can’t see and I can’t walk or paint, what’s the point?” she says. “But I’m OK with it. I’ve designed my life so that I can say what I want, do what I want and spend all my time with my kids. I’m obsessed with every last little thing because it’s all gonna be gone. I’m super, super lucky.”

Partly because they could afford a small house in Austin and partly because she has Austin-based art projects lined up over the next two years, Emily relocated her family — including three turtles, two dogs and three cats — there earlier this year. She’ll be creating a large-scale mural installation and exhibiting her paintings at a new gallery that the screen printing company Obsolete Industries is opening in March 2016, timed to the music and film festival South By Southwest.

Obsolete owner Billy Bishop, a friend of Emily’s, built the inaugural show around her. “I appreciate Lydia’s political views, what she’s doing for MS,” he says. “And her style is so bold and imaginative — her work speaks to me, it holds me.”

Emily will also exhibit her oil paintings — portraits of refugees — in a solo show at Garboushian Gallery in Beverly Hills next fall.

“It’s amazing that she can even paint, given everything,” says gallery co-owner Herair Garboushian. “She just keeps on going and fighting — and such great quality paintings. It’s mind-boggling.”

The streets, however, remain her preferred canvas.

“The goal is to educate toward tolerance,” Emily says. “Out of the thousands of people that walk by my murals, if just one person researches what I’m talking about — whether it’s African culture, sex trafficking, Tibet — and gets slightly more educated, then I’ve achieved my goal. I’d be done.”

ALSO:

Spielberg returns to Universal Pictures

GOP Debates: We need an elimination round already

Passed over three times, N.W.A is elected to Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.