Great Read: Old-time music at a ranch? It’s an American idyll

Musicians John Grimm and Beverly Smith perform before an audience in the living room at David Bunn’s farmhouse in the Santa Paula area on May 24, 2015.

- Share via

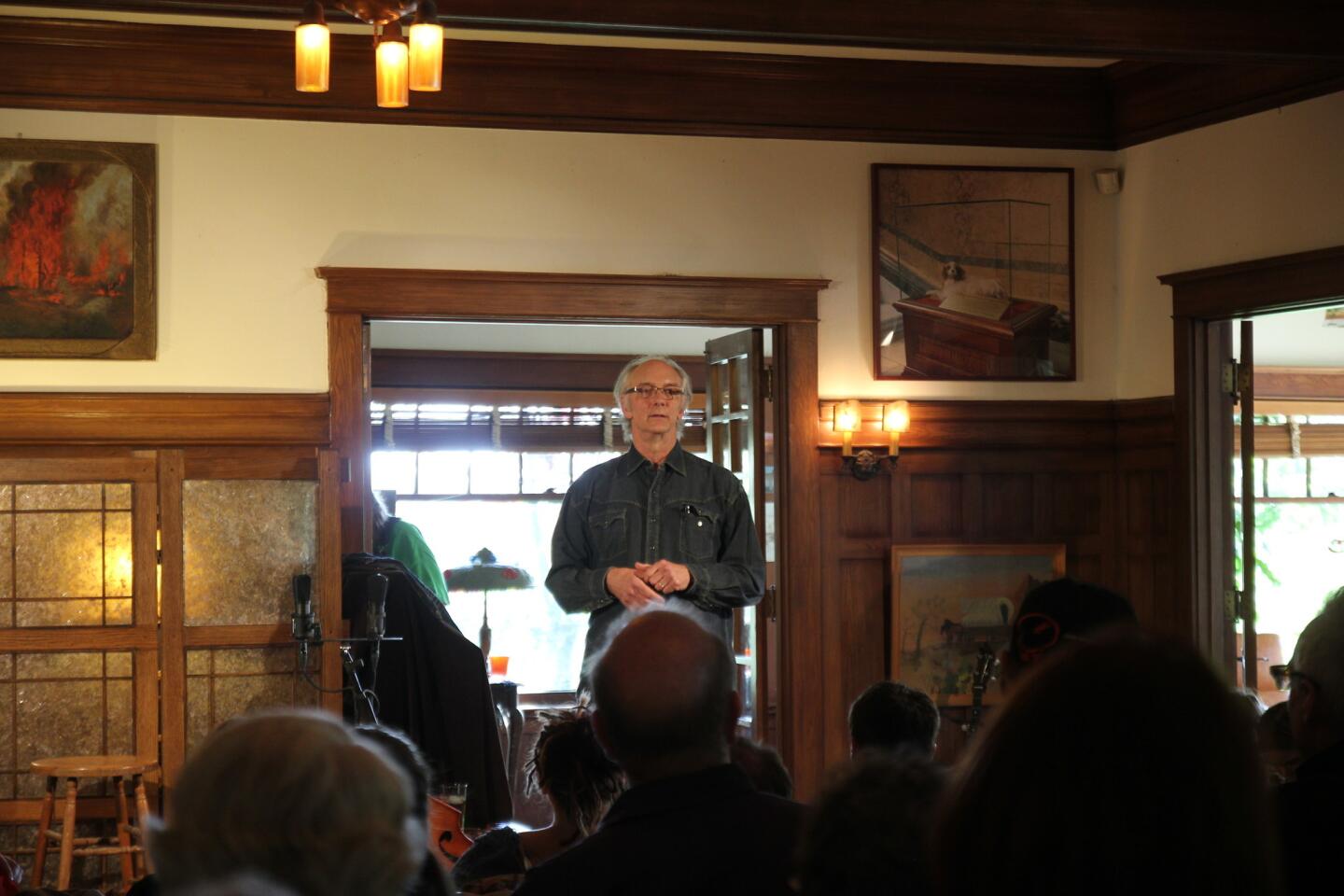

reporting from SANTA PAULA — It is late in the afternoon, that time when the light begins to soften and the orange groves seem to shiver in the breeze. More than six dozen people have piled into a century-old farmhouse in the Santa Clara River Valley for an old-time music concert.

John Grimm and Beverly Smith, a pair of musicians from northern Georgia, lightly pick at the strings of their guitars. Notes reach up and then tumble down as they launch into the Carter Family tune “East Virginia Blues #2.”

“I am just from East Virginia, with a heart so brave and true,” the pair sings, Smith’s twangy vocals bubbling up above Grimm’s lower register. “And I learned to love a maiden with eyes of heavenly blue.”

Heads bob. A field spaniel trots through the room. People snack on tangerines freshly picked from the trees outside. As the musicians reach the song’s final bars, the audience is humming along.

This very intimate show is the brainchild of David Bunn, an artist and citrus farmer in Santa Paula who for the last six months has hosted a series of concerts in his living room. Musicians from all over the country — Georgia, North Carolina, West Virginia, Texas, Missouri, Virginia and Los Angeles too — perform fiddle-heavy, banjo-laden roots music of the American South, along with new tunes they’ve created along the way.

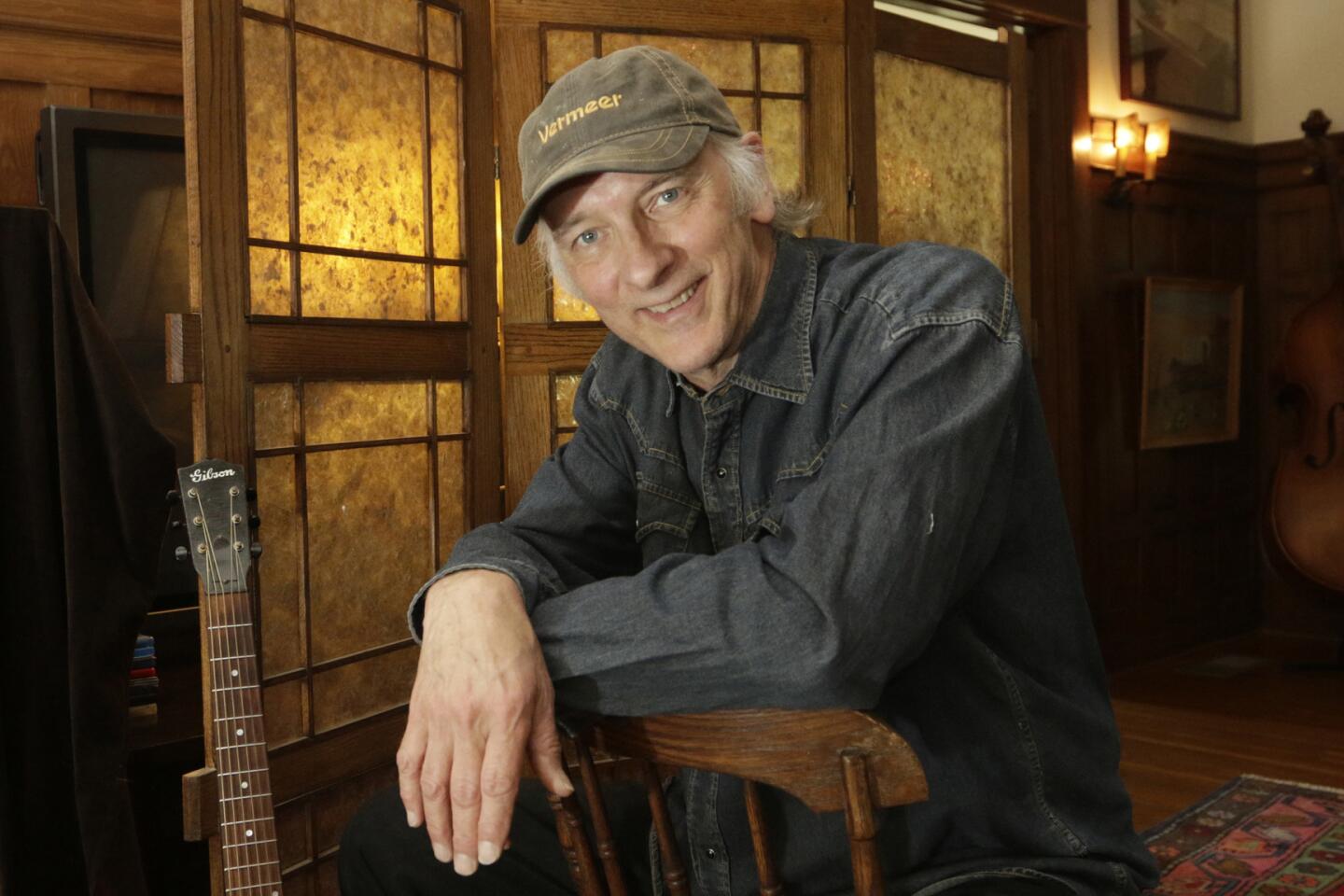

“We could have done these outside with amplifiers, but this is really about being in a close space,” says Bunn, who checks in at more than 6 feet tall, wears a baseball cap, and retains a dash of his native North Carolina drawl. “It’s about gathering together a community of friends and interested people. There is no stage; there is just the same shared living room floor.”

At a time when music is available everywhere — in cars, on computers, cellphones and MP3 players, as well as in countless bars, clubs and concert venues across Los Angeles — the idea of driving more than an hour and a half to a house concert in the middle of the Santa Clara River Valley might seem like the sort of thing only the most die-hard devotee would do.

We could have done these outside with amplifiers, but this is really about being in a close space. It’s about gathering together a community of friends and interested people.

— David Bunn, artist and citrus farmer

But there are other reasons to make the pilgrimage to Bunn’s farm.

Consider the setting: The rambling 1908 Craftsman farmhouse that Bunn shares with his wife, Ellen Birrell, an artist who is also co-founder and editor of the arts magazine X-tra, is tucked into a grove of lemon and tangerine trees, the very picture of California idyll. A wood-paneled living room harbors the perfect acoustics for an evening of amplification-free music. During intermission, guests can wander among the citrus trees, scavenging for pieces of fallen fruit. (I’ve never had sweeter lemons.)

Of course, there are the performances: down-home shows that get your toes tapping to soulful ballads about lost loves and untimely death.

And then there’s the journey itself. The roughly 90-minute drive (in good traffic) takes you from freeways to highways to country roads to dirt lanes to Deep End Ranch, which resides safely off Google Maps. It’s the sort of place that encourages you to put away your cellphone and, for the course of an evening, just listen.

I came upon Deep End by accident, when an artist friend forwarded me a flier and ordered me to RSVP, saying it’d be a fine opportunity to listen to some good tunes and drink beer in an orange grove. I found myself returning for the entire five-concert series. These days, music shows can feel relentlessly commercial — the ticket fees, the beer sponsors, the branded T-shirts. Here was something that felt more like a family gathering.

“It’s sitting and telling stories and just playing tunes,” says West Virginia banjo player Ben Townsend, who rode his bicycle across the country for a stay at Deep End late last year. “I’m not ‘performing.’ I’m not being anybody but myself. It’s like what I do with other musicians in my living room. You’re just sharing with people, and that’s not something you get to do in too many places.”

::

And, of course, there’s the chili. Spicy, gut-warming, shirt-staining. Big, bubbling pots of it, served with architectonic piles of cornbread at communal tables — all of it made by Bunn’s sister and brother-in-law. For the aim at Deep End isn’t just to put on a show. It’s to generate a bit of face-to-face neighborliness between musicians and whoever else happens to show up.

“It’s a way of using this place,” Bunn says. “Ellen and I didn’t move out here to be two people in a big space. We really wanted to share it.”

The Deep End Sessions concert series, in fact, began life as an artist residency program.

Bunn has a master of fine arts degree from UCLA — where he studied under towering art world figures such as Chris Burden and Robert Heinecken — and his conceptual works are in the permanent collections at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Museum of Contemporary Art in L.A. His pieces play with the nature of knowledge and communication. For one long-running series, he worked with the discarded card catalogs of the Los Angeles Central Library. For another, he examined the reading and musical links between Liverpool and L.A.

About a decade ago, he and Birrell decided to buy Deep End after seeing it listed as a property of the week in The Times’ real estate section.

“We’d been in Los Angeles for 25 years, and we were ready for a break,” he says. “We’d been talking about doing something like hosting an artist residency program, and this property was perfect for that. Plus, Ellen was interested in keeping horses. This was a way of doing all of that without moving some place like Bozeman [in Montana]. We are still L.A.-adjacent.”

The couple hosted their first residencies more than eight years ago. Since then, they’ve had artists such as Diego Gutierrez, a filmmaker and visual artist from Mexico City, as well as Sadie Benning, from Chicago, who is known for producing abstract pieces that evoke jigsaw puzzles.

In 2014, they decided to open the residency up to musicians. “I’m from central North Carolina and I’ve always been interested in old-time music,” Bunn says. “I had my first guitar when I was 14. I play rhythm guitar in an old-time tradition.”

Last year, national fiddle champion Aarun Carter, from Colorado, and Ozarks guitarist Jonathan Trawick showed up for a stay at Deep End.

Concerts at the Deep End ranch are always followed by a communal chili dinner. Guests gather for a bowl in David Bunn’s kitchen.

“They were some of the younger practitioners of this very traditional music,” Bunn says. “Music that has been passed down orally — nothing has been written down. These folks have learned it all from the masters.”

With the help of sound engineer Stephen Schauer, he recorded the pair playing in his living room and released an album of its work. He also organized a small house concert, to which he invited friends and local fans of old-time music.

The success of that event inspired the current concert series, which began in early December and ended Sunday. Bunn is now plotting a follow-up series, which kicks off in November with a performance by bluegrass guitarist Chris Luquette.

For the musicians, these types of house concerts also represent a break from the pressures of working in commercial venues.

“You’re not worried about guarantees and how many people will show up and some big sound system,” Smith says. “You just play.”

The Deep End Sessions concert series consisted of five house concerts that ran from December through May and drew musicians from Texas to West Virginia. John Grimm, left, and Beverly Smith get ready to play.

She has performed at house concerts for more than a decade, but has seen a rise in their popularity over the last couple of years. On their way to Deep End Ranch, she and Grimm played house gigs in Birmingham, Ala.; Albuquerque; Phoenix; and Santa Barbara.

Financially, they are no replacement for commercial shows, but she says they are a welcome break. “You’re not the musical background in some bar,” she says. “It’s always a listening audience.”

::

Bunn has purposely kept the concerts small, inviting a limited list of friends and musicians, and accepting others if there’s room. Directions to the ranch are sent out only if a guest has submitted an RSVP.

“I didn’t want it to turn into something where people come for a party and they don’t come for the music,” he says.

Joe Wack is a banjo player from West Virginia who lives in L.A. He played in the first concert in the series and helped connect Bunn to some of the other musicians on the lineup.

“The musicians often stay there and record for several days, which means by the time they play a show, they’re really relaxed,” he says. “And, afterward, there’s always a jam. You play and talk and sometimes there’s some alcohol involved.”

That’s a big part of the evenings at Deep End: the informal jam sessions that take place after dinner, when locals join in with the headliners for musical sessions that can go on for hours.

Musicians John Grimm and Beverly Smith of Georgia were the last act of the Deep End Sessions concert series. The pair drew a standing ovation with new compositions, vintage tunes and a few Carter Family classics.

Bill Bartels, who lives in the nearby town of Bardsdale, has come out for every show — and always sticks around for the jams. (He plays guitar and banjo.)

“You can gather with friends and learn about music,” he says. “There’s an engagement and a civility. Everyone brings their best stuff.”

Bunn has created a warm space that is all about community. After the last string has been plucked and the chili pots emptied, he and Birrell personally see their guests off with hearty handshakes and back-slapping hugs.

The sky is inky as I wander through the lemon trees back to my car, filled with food and beer and the sounds of old-time fiddles, knowing that for an evening I got to be a part of something special.

Twitter: @cmonstah

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.