Seven directors ‘weaponize storytelling’ to stand against hatred and violence

- Share via

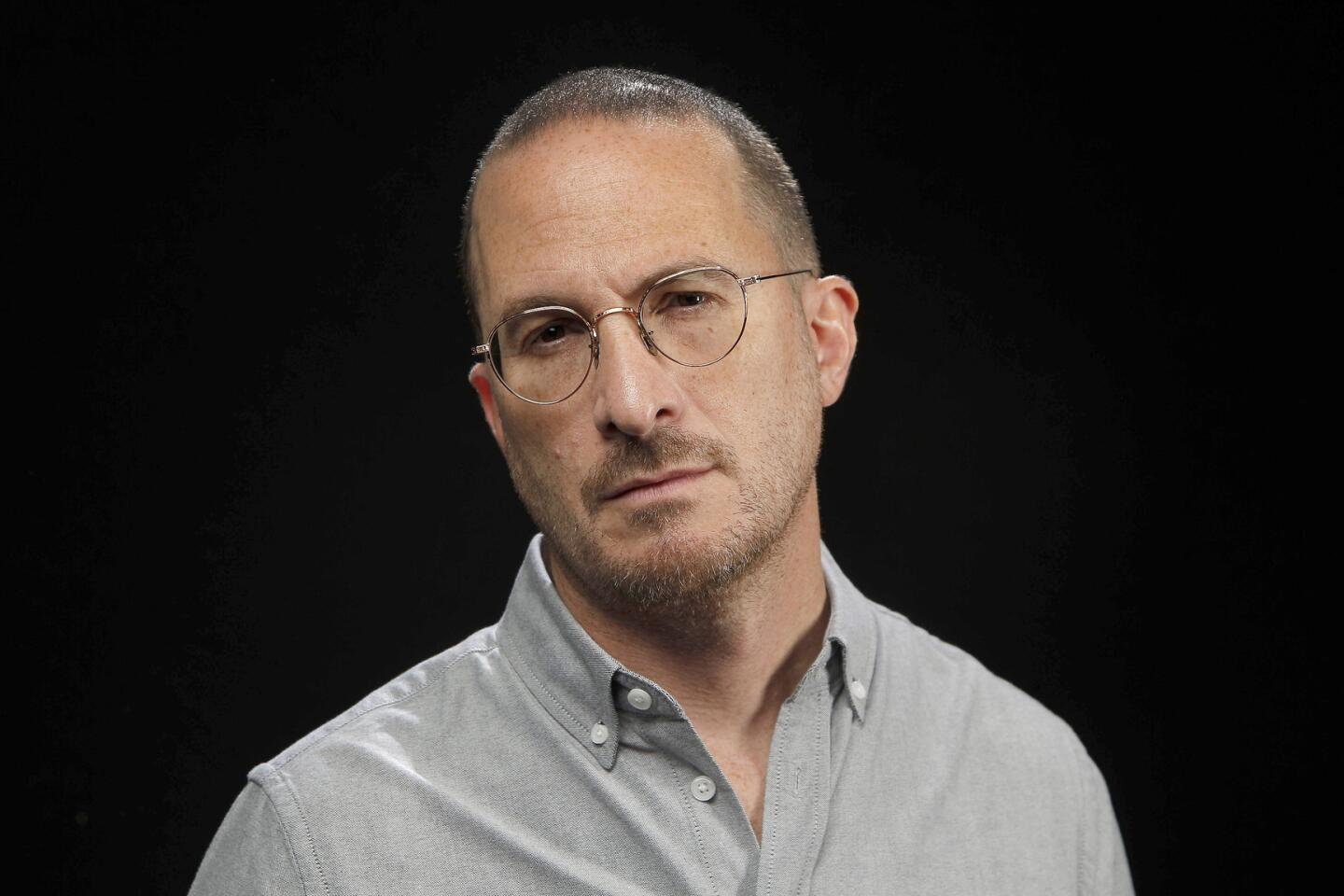

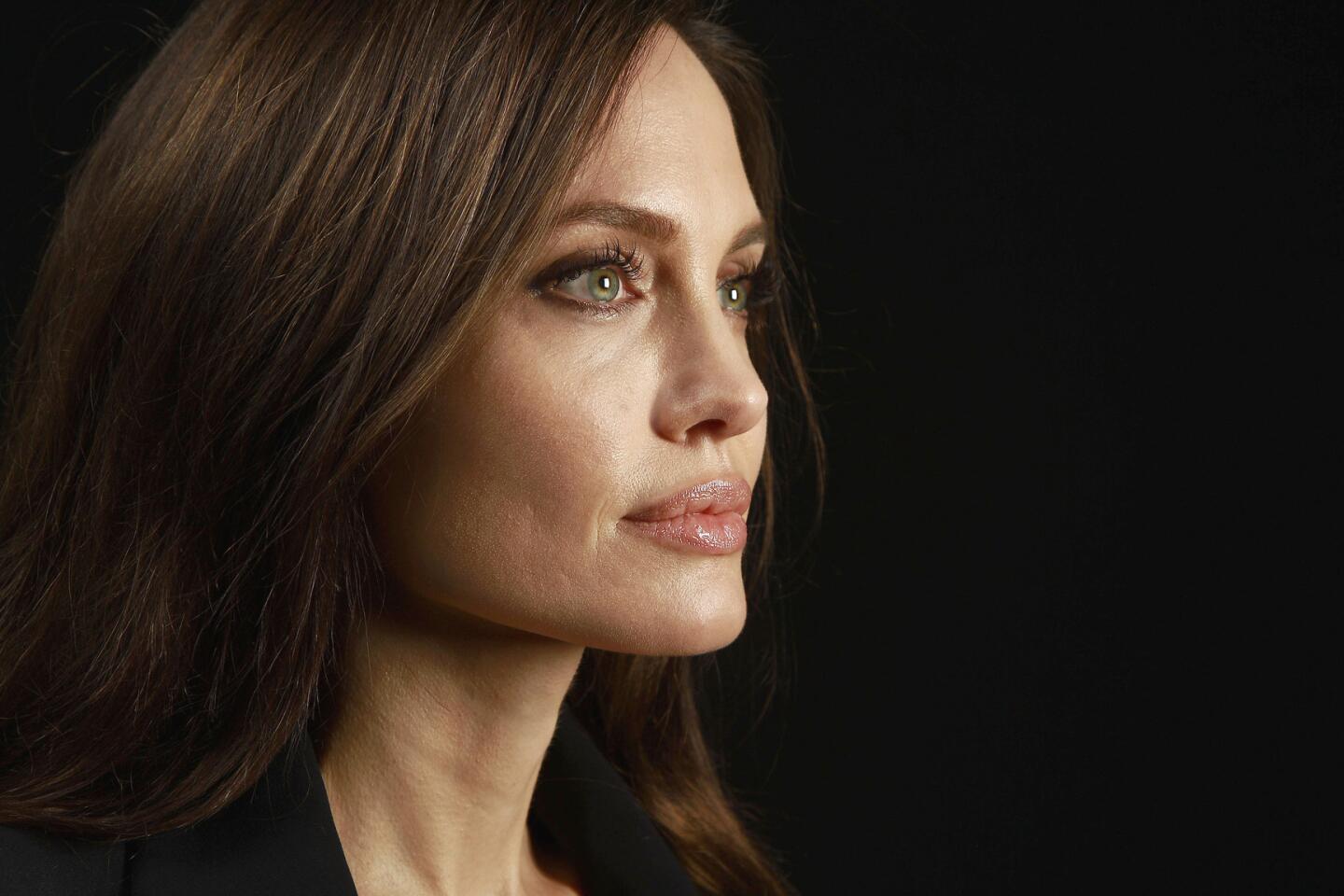

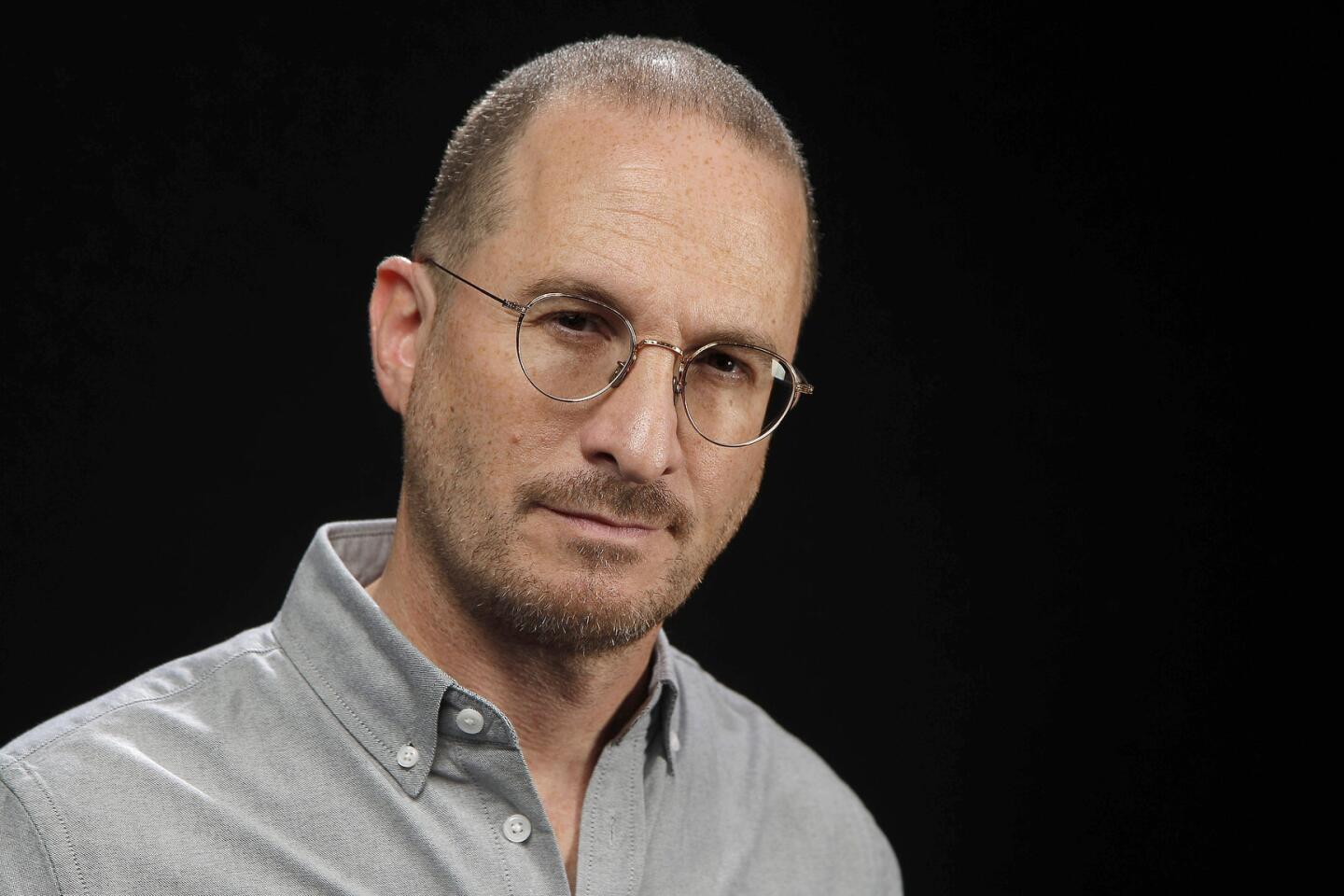

The Envelope gathered seven filmmakers for its annual Directors Roundtable — with the strongest representation of women to date. The wide-ranging conversation, led by The Times’ Mark Olsen, included Darren Aronofsky (“mother!”), Sean Baker (“The Florida Project”), Kathryn Bigelow (“Detroit”), Guillermo del Toro (“The Shape of Water”), Greta Gerwig (“Lady Bird”), Angelina Jolie (“First They Killed My Father”) and Jordan Peele (“Get Out”). The group found commonalities in their works, the outsider stories, the power of the parable, the emotional truths. And then there was that director who called Aronofsky’s “mother!” weird, how’d that go over? Here’s an excerpt from their conversation edited for length and clarity.

Mark Olsen: Darren, I’d seen you mention that before shooting “mother!” you’d shown your actors the Luis Buñuel film “Exterminating Angel.” What does that do for you or for your actors when you’re getting ready to shoot?

Darren Aronofsky: Just probably so they can see there’s a history of weirdness, it’s not just me. And that’s what Luis Buñuel did in that film was to take a huge social, cultural issue and reduce it to a single room. And I was trying to think about how to talk about — the largest forest fire in the history of Canada happened this summer, the superstorms that just happened this summer. It’s a very hard thing to relate because it’s such a huge magnitude. But everyone remembers the house guest who spilled red wine on the couch. So that was the breakthrough. I was, like, “Oh, this is our home, this planet. What if I made it all about a home and stuck Mother Nature in the center of it, and sort of let humanity invade?”

Guillermo del Toro: What I share with Darren is the power of the fable, the parable. I mean, when you make a parable you can approach these things. The rest is symbols that you can harvest from pop culture or you can harvest from classical painting, from photography. I consider myself a very curious sort of magpie that goes to any form of culture that attracts me.

Jordan Peele: Unlike Darren, “Get Out” didn’t start with me having something to say. It really started with me wanting to entertain, wanting to scare. And as I explored what that was, the movie kind of taught me what it was about. I realized there’s something inside of me that has been trying to tell myself to express. So from that point forward I knew I wanted to make this a thriller about race. And it became looking at movies that have figured out the social thriller, so, “Rosemary’s Baby,” “The Stepford Wives,” the way those movies made very elegant but fun statements about gender, that was a signal to me that you could pull that off with race.

WATCH more Envelope Roundtables »

Angelina, where does the storytelling process on your film start?

Angelina Jolie: It was that I had read this book years ago. For me, it’s very much about the country. I was very humbled every day to be a part of the filmmaking of someone else’s history and to really listen to the community. It’s a beautiful thing about making a foreign film is that you really are there listening to the language of, you know, listening to the music of their language, listening to the way they would speak, listening to the way — you can only direct to a certain point because you’re really trying to be a vessel to allow the country to speak.

Director Angelina Jolie explains how she was mindful of the emotions that could be evoked by the scenes she was re-creating to film “First They Killed My Father” in Cambodia.

With “Detroit” the scale of the movie is so interesting, the way it sort of zooms back and forth between the really specific and a larger-scale look at it. Where is the point of entry on that process?

Kathryn Bigelow: Well, there are multiple points of entry. I was introduced to the material right about the time that the decision not to indict the officer in the Michael Brown shooting happened. And so, looking at this material, it was 50 years ago, then listening to the fact that the officer was not indicted, and it just kind of conflated in my mind: Here’s something that happened 50 years ago and yet it’s so contemporaneous. And then the film began to kind of reveal itself as I did a lot of research and began to dig into the material.

The last few films you’ve made, the ones you’ve made in collaboration with writer Mark Boal, you seem to have this interest in cinema as a form of journalism. Do you feel like there’s some sort of emotional truth that wouldn’t be told in, say, a documentary?

Bigelow: Maybe there’s a place where drama and documentary kind of fuse, and that’s sort of a place that interests me. [To Jolie] In a way like your film too, revealing a culture and an environment that has a pretty heightened degree of authenticity, meaning the documentary but at the same time, there are composite characters and there are fictional elements. Also, it becomes very topical and timely, and that’s where the journalistic aspect comes in.

“Detroit” director Kathryn Bigelow and “The Florida Project” director Sean Baker explain how they were drawn to the space that blends fictional narratives with stories rooted in facts for their films.

Sean, your movies are really rooted in a sense of place and exploring a specific subculture. Are you usually drawn to a location or someone that you’ve met there?

Sean Baker: It’s really project by project. In the case of “Florida” it was really about my co-screenwriter sending me news articles about the situation happening in the Kissimmee and Orlando area in Florida. So it stemmed from journalists having explored this topic — children living in motels outside of the most magical place on Earth. I like what you said about the fusion there, that hybrid. And I think that that’s how I approach it, and it’s the cinema that I’m really finding the most fascinating right now and the most interesting, where that line is blurred between narrative fiction filmmaking and documentary-style filmmaking.

It never seems like you’re some outsider who’s come in. Is it difficult for you to feel like you’re telling their story correctly?

Baker: 100%. For the last five films I’ve been from outside of the group that I’m focusing on. It has to be done in a respectful and responsible way, and you’re not being that voice, you’re only amplifying the voice. You have to spend the time. It’s pre-production, it’s really just about working with the community, seeing who’s enthusiastic, who wants to be involved, and involving everybody.

Greta, at what point in the process did you realize Sacramento was going to be so important to the story?

Greta Gerwig: I always knew that I wanted to make a film that took place in Sacramento and was about Sacramento because I think one of the things that movies do and cinema does better than almost any other art form is capture place. I felt like I could shoot it lovingly and truthfully. And that was exciting to me. And also, I think the more specific something is, the more universal it ends up becoming. So I was interested in telling a story of a family, and of a girl, and of a time — we’re getting into the war in Iraq, and the erosion of the middle class. But also, this is just her senior year of high school, and her mother’s having trouble letting go. And I felt like the more clearly I could paint that world with what I knew, the more everyone else would feel like, “Oh, that’s my story, too,” even though it’s not.

Guillermo, your film is set in early 1960s Baltimore but it has this real fantasy feel to it. And yet the emotions to it are so real.

Del Toro: Well, it was ’62 for a reason. Because it’s about today. The movie’s about today and about the other and about the fact that ’62 is the year when there’s a Madison Avenue fabrication of America, the postwar affluency, suburban life, the space race. Everything’s about the future and abundancy if you’re a certain race and a certain class. But if you’re not things are exactly as bad as they are right now. And I wanted to talk about things now, and if you’re going to approach parable, which is what Darren did, and what I find very valuable, you don’t want to root it in now. It’s too direct for me. I like the idea of being able to have people lower their guard with the “Once upon a time,” you know, and then listen. And then emotionally, I try to make it very real and very specific to me. I felt an urgency to make almost an ointment against the vulgarity and the brutality of what we’re living. In every aspect, the most basic pacts of civility have been broken and destroyed. And I wanted to see, can I talk about love without sounding disingenuous?

Director Guillermo del Toro explains that ”The Shape of Water” is set in 1962 ”for a reason. Because it’s about today. And about the ‘other’ ... I wanted to talk about things now.”

Gerwig: When you guys were talking about fables and making it more allegorical in that way, even though I don’t know that necessarily anyone would connect this to “Lady Bird,” but I read a lot of lives of the saints when I was working on it. Even though it was about a teenage girl, I wanted it to feel like it was connected to the lives of the saints — like St. Francis, on the one hand, was this obviously amazing man who renounced everything and went to live in nature and experienced love for the world. But he was also just an annoying 17-year-old who took off all of his clothes in the town square and was, like, “I don’t need your money, Dad.” I was just thinking about him as a teenager and what that would’ve been.

Darren, one of the challenges for people as they’ve been encountering “mother!” is trying to unpack which biblical parable is which. How did you kind of craft this story that’s set in the modern day but obviously has relationships to the Bible?

Aronofsky: Well, the Bible for me was just the structural solution, because I was trying to think about how to tell the story of people. I’m a fan of these old stories that have been told for a very long time. I’m not really interested in who those stories belong to or if they really happened. I think that takes away from their power. You can use them to talk about life in the 21st century because they have all the structure that you need for the heroes that you’re creating. So, for me, that was the breakthrough. I had this kind of emotional story about a marriage falling apart, and then I had this kind of allegorical idea about the state of the world from an environmental perspective. But the Bible was, like, “Oh, that’s a great way to tell the story of people, first a story with one man, then one woman, then the first murder, and then everything goes to hell, and then we have to throw everyone out, and then we have to start again with birth.

“Get Out” director Jordan Peele says, “The sunken place is this metaphor for the system that is suppressing the freedom of black people.”

Jordan, the idea of the sunken place in “Get Out” has already entered the lexicon. Like, immediately, we were talking to people and “Oh, I really went to my sunken place.” And you sort of know what that is. Where did that idea come from?

Peele: You know when you’re going to sleep and it feels like you’re about to fall, so you wake up? What if you never woke up? Where would you fall? And that was kind of the most harrowing idea to me. And as I’m writing it becomes clear that the sunken place is this metaphor for the system that is suppressing the freedom of black people, of many outsiders, many minorities. There’s lots of different sunken places. But this one specifically became a metaphor for the prison-industrial complex, the lack of representation of black people in film, in genre. The reason Chris in the film is falling into this place, being forced to watch this screen, that no matter how hard he screams at the screen he can’t get agency across. He’s not represented. And that, to me, was this metaphor for the black horror audience, a very loyal fan base who comes to these movies, and we’re the ones that are going to die first. So the movie for me became almost about representation within the genre, within itself, in a weird way.

I find “Detroit” and “Get Out” to be really similar movies. Once “Detroit” gets into that hallway sequence, it’s so relentless. Was that level of intensity important?

Bigelow: I had the survivor accounts and I did have some people on the set who had actually experienced it. So I was very sensitive to what they had gone through, and also the memories of the three boys who were killed. But at the same time, trying to understand the systemic oppression, you know? How does this happen, where you’re completely unconscious with what you’re doing — for instance, the police officers, who, you know, have come out of a system where this is somehow permissible. We were just, like, it couldn’t have been like that and we’d turn to a survivor and they’d be, like, “Yeah, it was like that and it was worse.” So it was interesting, kind of trying to understand it, trying to re-create it and being horrified by it at the same time.

Jolie: There’s something that happens when you’re on a film, especially with people who have actually survived. And every single Cambodian crew member was affected by this war. Many of these children knew their parents went through this, but they never talked about what happened. But now they’re going to re-create a scene, and they’re going to see, and experience, and feel what the parent went through. We had to be really sensitive to that because it’s also a country not used to film. So you can’t say to the people down the road, we’re just going to blow these things up and you’re suddenly having the Khmer Rouge come back across the bridge in full uniform. You have to find a way to communicate to a country that doesn’t have a lot of cinema. It was making sure that we didn’t re-traumatize anyone. And I’m sure that’s something that you were all dealing with in many of these heavier issues, in that you know the sensitivity. And even though you’re all there for the same reason, we still had to do scenes where children were being hurt. I want to stop every five minutes and, you know, bring in a magician and have a thing.

Peele: It feels like all of these stories are exploring a missing piece of the conversation, right? The reason these movies worked and are beautiful and important is we all feel story is one of, if not the most important tool, weapon, we have against hatred and violence.

Bigelow: Especially now. You’re almost weaponizing storytelling in order to somehow contextualize the unthinkable.

Peele: And story promotes empathy, right?

Bigelow: Right, exactly, humanizing it. And also it allows you to agitate for change.

Del Toro: And we’re in, everybody says, “post-truth,” we’re in a post-truth time and all that. But what happens is, the discourse entrenches on two sides, on a dichotomy, so fast now.

Baker: So I have to say what you’ve done with this social thriller of yours is incredible, it really is. Because you’re using genre, which is the direct pathway to mainstream audiences. I was seeing your film in a packed house. You could feel the energy in the room. But then, the discussion that you sparked afterwards, incredible.

Peele: Thank you. This movie happened because there was a void in the conversation. “Get Out” was trying to say, “Look, you know this story is a genre piece, but you know what’s true here.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.