Column: Studio Visit: Hugo Crosthwaite and a Giant Dashboard Jesus, channeling Tijuana’s just-do-it spirit

Painter Hugo Crosthwaite in his studio in Rosarito. The artist, who was born and raised in the area, is known for painting elaborate canvases and wall scenes that depict Tijuana scenes in gritty and surreal ways.

- Share via

Reporting from Tijuana — Tijuana is known as a paean to improvisation. A man makes a house in the shape of a woman. Curio vendors transform the narrow aisle of tarmac between waiting cars at the international border into a thriving commercial venue. And, on the coast, just beyond the southern edge of Rosarito, a 75-foot sculpture of Christ rises from the hillside, its arms extended before the vastness of the Pacific Ocean.

The Sacred Heart of Christ was built over at least half a dozen years (the reports conflict on how many) by a man named Antonio Pequeño, in honor of his mother, who is buried at the site. Completed in 2006, it is neither an official government monument, nor was it commissioned by the Catholic Church. Instead, the towering Jesus was simply an act of faith — built piece-by-piece, without permission, just above a high-end housing development.

For artist Hugo Crosthwaite, who grew up nearby, the monument represents the freedom of living in the Tijuana area — a place where the rules as we know them do not always apply.

As part of our visit, Crosthwaite took me to visit the Sacred Heart of Christ sculpture that overlooks the southern edge of Rosarito. Built by a local man in honor of his mother, Crosthwaite says that, for him, the icon represents Tijuana’s do-it-yourself culture.

“One could never build this in the U.S. with all the state and federal regulations — not to mention the controversy that it would bring,” he says. “It’s a kitschy-looking monument, but there it is, standing in all its glory around expensive houses that expatriate Americans are living in.”

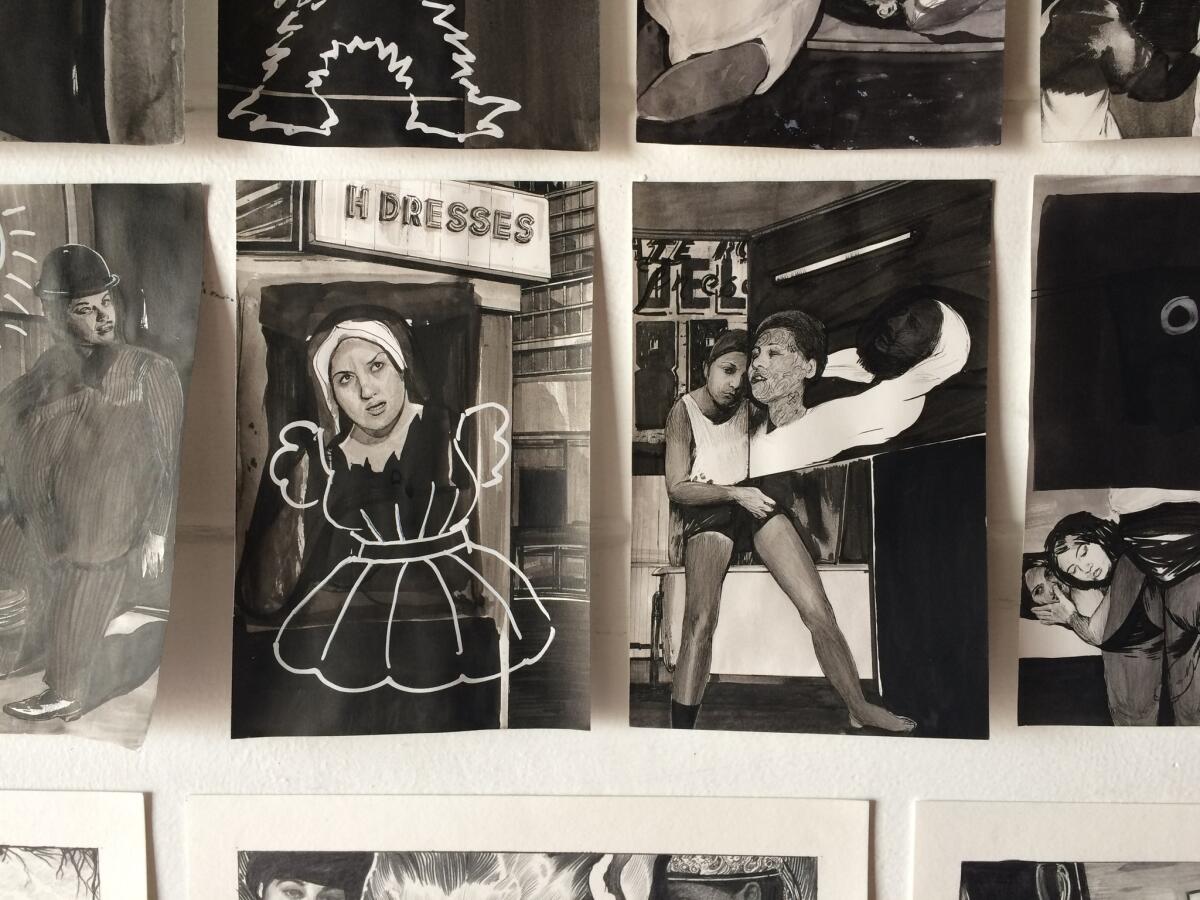

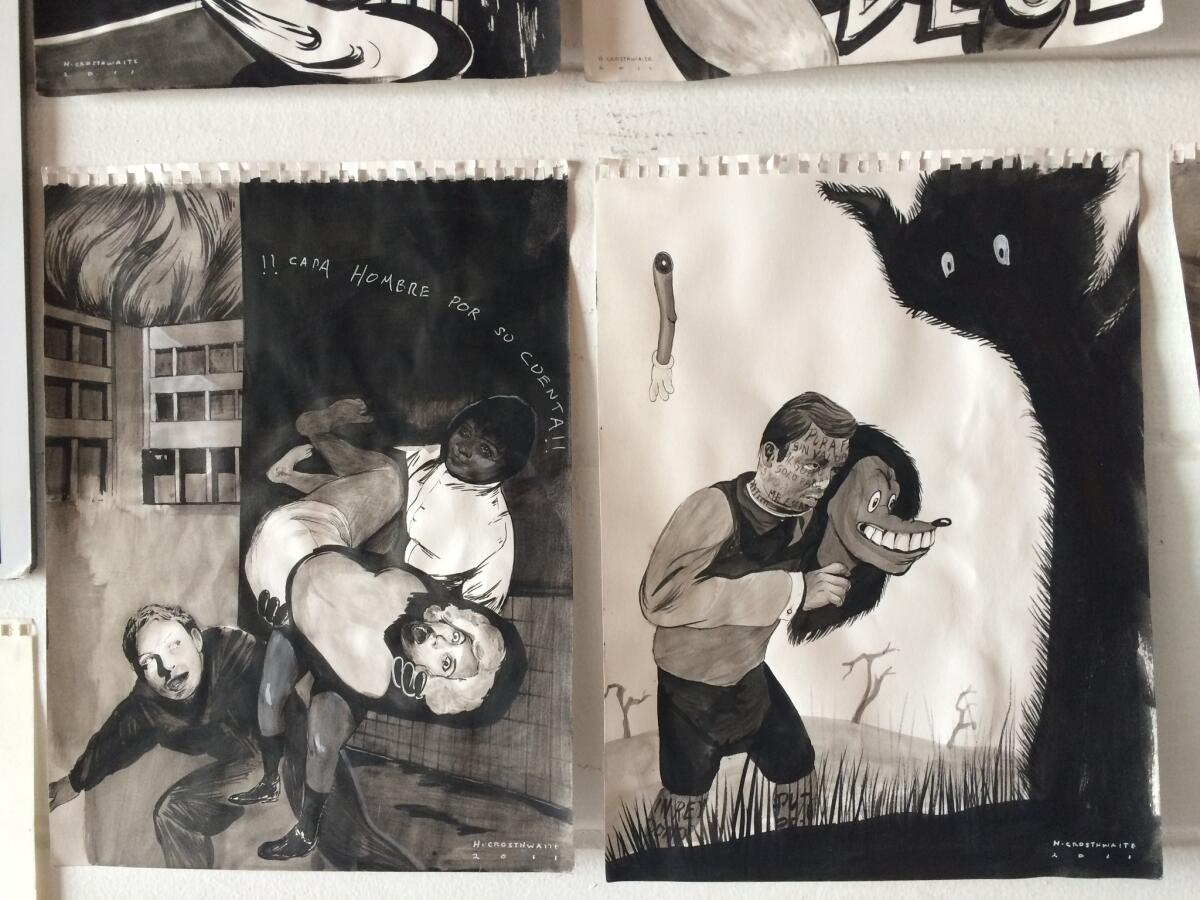

This sense of freedom — for better and worse — is something that often materializes in Crosthwaite’s work: intricate black-and-white drawings and paintings that capture not-quite realities inspired by Tijuana’s landscape.

His pieces often feature fantastical creatures: sci-fi goblins and pre-Columbian deities. But they also include Tijuana’s impromptu architecture, its everyday faces, the odd juxtapositions one might see in the city, where a single street corner might offer views of a humble taco vendor and the open windows of a seedy brothel.

A view of Crosthwaite’s large-scale painting ‘Urbanscape From a Bizarre Present,’ which was shown in Tijuana’s TJ in China ProjectSpace in 2014.

Crosthwaite was born in Tijuana and reared in Rosarito, 14 miles to the south. But like many Tijuanenses, he was educated in San Diego, receiving a degree in applied arts at San Diego State University in the mid-1990s. In this way, he is an inveterate child of the border. “I never ‘learned’ to speak English,” he says. “I was born with English. I just grew up with both languages.”

He says the border region provides a distance from authority that make it a dynamic place to be an artist — one in which credos haven’t been set in stone. “Tijuana is the farthest point from Mexico City,” he says. “As far as Mexico City is concerned, we might as well be Alaska.”

But he says that is changing. Over his career as an artist, which has taken him from the Tijuana area to New York City and back again, Crosthwaite says Tijuana’s cultural profile has begun to evolve.

Drawings line the wall at Crosthwaite’s studio. As a young man, the artist was drawn to the work of French illustrator of Gustave Doré, who was known for his roiling, atmospheric scenes.

“I remember like 10 years ago, some curator from Mexico City came and insulted us all,” he recalls. “He came and said something like, ‘Tijuana is of interest to the world, but the artists are not.’

“That motivated a lot of people,” he chuckles. “We artists, we often do things out of spite.”

Now, he says, the region’s artists receive grants from Mexico City organizations and get shows there, too. And Tijuana artists can be found showing all over the country. Last year, Crosthwaite received the grand prize at the FEMSA Biennial in Monterrey.

Crosthwaite is inspired by baroque art and 19th century illustration, but he infuses these with a fantastical sensibility that draws from a wide gamut of sources — from Mexican folk traditions to U.S. popular culture to the landscape of Tijuana.

But despite the success, Tijuana’s spirit is still that of live and let live and do and let do.

On a drizzling Saturday morning, I popped over to Rosarito to visit Crosthwaite in his studio, which is attached to his family’s home on the city’s main drag. But before settling in to look at the inky works that line the walls of his space, we hopped a cab to the southern fringes of the city in an impromptu pilgrimage to Pequeño’s Christ.

The artist says the local U.S. ex-pats refer to it as the “Giant Dashboard Jesus,” since it resembles the cheap, plastic Christs that are sold to decorate the interiors of cars.

As the taxi winds its way up the mountain, Crosthwaite points out the massive vacation compounds wrapped in ocean-view terraces. “These are the American dreams,” he says.

Then he gestures at the Christ offering his stiff embrace straight above. “And this is the Tijuana dream,” he adds. “A Christ for his mother.”

See more of Hugo Crosthwaite’s work at hugocrosthwaite.com. You can also find his work at Luis De Jesus Los Angeles. And for more about the artist, Crosthwaite and I chatted in a separate interview about his sources of inspiration during a solo exhibition of his work at Luis De Jesus Los Angeles in Culver City this past spring. The artist has exhibited extensively at galleries and museums in the United States, and was included in the California-Pacific Triennial at the Orange County Museum of Art in 2013.

Find me on Twitter @cmonstah.

Series: Tijuana’s Generation Art

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.