Guggenheim Memorial Foundation announces new fellows — and pays tribute to grantees from California

- Share via

During a career that’s spanned almost five decades, artist Anthony Hernandez has applied for a Guggenheim Fellowship roughly half a dozen times.

“I always got the letter saying, ‘I’m sorry to inform you that...’” he says.

Last year, when the application period rolled around, Hernandez says he wasn’t planning on applying again. But his wife, novelist Judith Freeman, who was the recipient of a Guggenheim grant in 1997, urged him to give it another shot.

“I said, ‘OK, but this is the last time,’” he recalls.

It’s a good thing Hernandez submitted the application.

The Los Angeles photographer, known for his unblinking images of the Southern California landscape, is one of several dozen artists, scholars, writers and scientists across the United States to receive 2018 Guggenheim Fellowships — the complete list of which is expected to be released Thursday morning.

“It’s terrific,” says Hernandez. “[Photographer Edward] Weston was my first hero, and he got one of the first ones. A lot of my friends have gotten them. And I finally got one.”

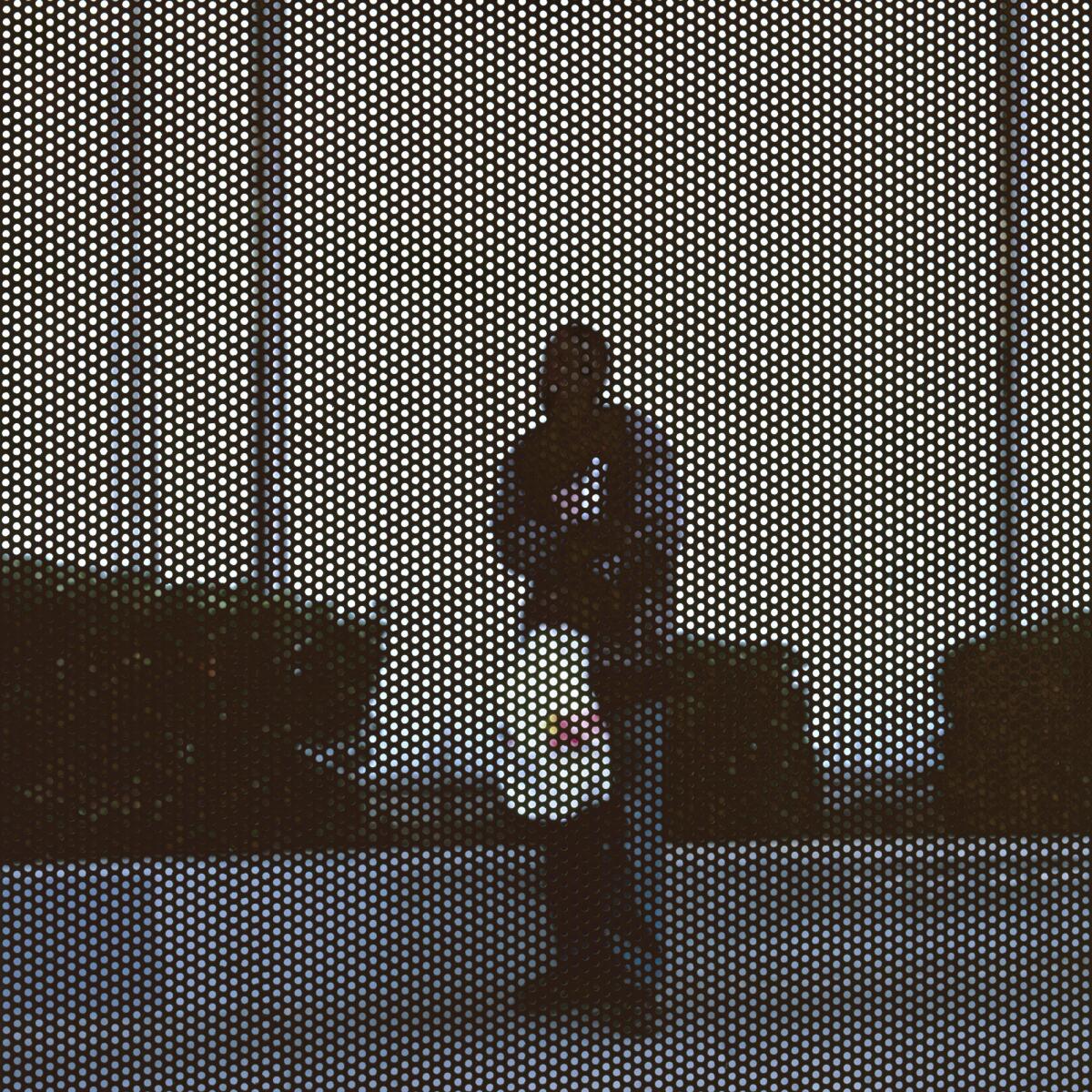

He’ll use the grant on a series of works in which he shoots images of Los Angeles and other locales through a screen that renders ordinary corners of the urban landscape as abstracted fields of dots.

“They’re very ambiguous,” he says of the new work. “You’re not quite sure what they’re made of or what you are looking at.”

We feel that our presence in California, both Northern and Southern, has been hiding in plain sight. But we have never focused on it in particular.

— Edward Hirsch, John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation

The grants, whose amounts are not disclosed, are awarded annually by the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation in New York — and their ranks include high-profile recipients such as essayist James Baldwin and choreographer Martha Graham.

As in many other years, the new list includes a healthy representation from Southern California: 17 thinkers and artists who hail from or are based in the region. This includes poet Amy Gerstler, historian Nile Spencer Green, astronomer Shrinivas R. Kulkarni and bestselling memoirist Roxane Gay — the latter for a project that will take her between Los Angeles and Lafayette, Ind., where she is on the faculty at Purdue University.

“We tend to give 10% of the fellowships to Southern California artists and scholars,” says foundation President Edward Hirsch, a poet who was also a Guggenheim grantee in 1985 (before joining as president). “It’s very striking.”

The California presence is so striking, in fact, that the foundation is hosting a special reception for West Coast fellows at the Annenberg Space for Photography in Century City later this month.

“We really wanted to do something and be more present to our fellows on the West Coast and to engage in a continuing conversation about the foundation,” Hirsch says. “We feel that our presence in California, both Northern and Southern, has been hiding in plain sight. But we have never focused on it in particular.”

The private soiree will provide an opportunity for Guggenheim fellows past and present to connect with one another and with the foundation. They are part of a very select club: This year, almost 3,000 individuals applied for grants; only 173 received them.

“It involves an extremely rigorous screening and selection,” says newly named fellow and UC Irvine humanities professor Edward Dimendberg. “You don’t just get a Guggenheim. There are all these levels of screening, committees and then the board of trustees.”

Dimendberg will use his grant to complete a book on a history of urban theory that looks at the ways L.A.’s urban design was treated as exception rather than rule by theorists throughout the 20th century.

“I’m on cloud nine still,” he says of receiving the award. “Just look at the website and the different fields. People who were leaders in those fields got Guggenheims. I’m incredibly proud and very humbled.”

The John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation was established in 1925 by Simon and Olga Guggenheim in memory of their son, who died of an illness at age 17.

The first crop of fellows, announced the following year, consisted of 14 men and one woman working in the sciences, social sciences and humanities. The lineup included pioneering African American scholar Isaac Fisher, who studied global race relations, and composer Aaron Copland, who used his grant to research contemporary European music. (Copland had yet to write the compositions for which he became most famous, including “Appalachian Spring” and “Fanfare for the Common Man.”)

From the fellowship’s earliest days, California thinkers were well represented.

One of the first visual artists to receive a grant was from Los Angeles: Isamu Noguchi, in 1927. With the grant money, he went to Paris to “acquire proficiency in stone and wood cutting.” There he studied under Modernist sculptor Constantin Brâncuși, whom he once described as a craftsman “unsurpassed in the technique of handling stone, metal and wood.”

An untold number of other California cultural figures have also received grants. Among them: pop conceptualist Ed Ruscha (1971), social practice pioneer Suzanne Lacy (1992), architectural historian Esther McCoy (1979), mathematician Michael Freedman (1981), novelist Viet Thanh Nguyen (2017) and several associated with the L.A. Rebellion, the school of independent black filmmakers that emerged out of Southern California in the ’70s and ’80s, including Charles Burnett (1980), Haile Gerima (1979) and Julie Dash (1981).

Chris Kraus, the L.A.-based author of the experimental novel “I Love Dick” and founder of the arts publisher Semiotext(e), was a Guggenheim fellow in 2016.

“It’s a validation and a show of support,” she says. “As an artist, you have to keep telling yourself you don’t need that validation. You have to be able to do without it. But it’s nice when it comes.”

Kraus put her award toward completing her latest book, “After Kathy Acker,” a biography of the punk poet and writer published last year.

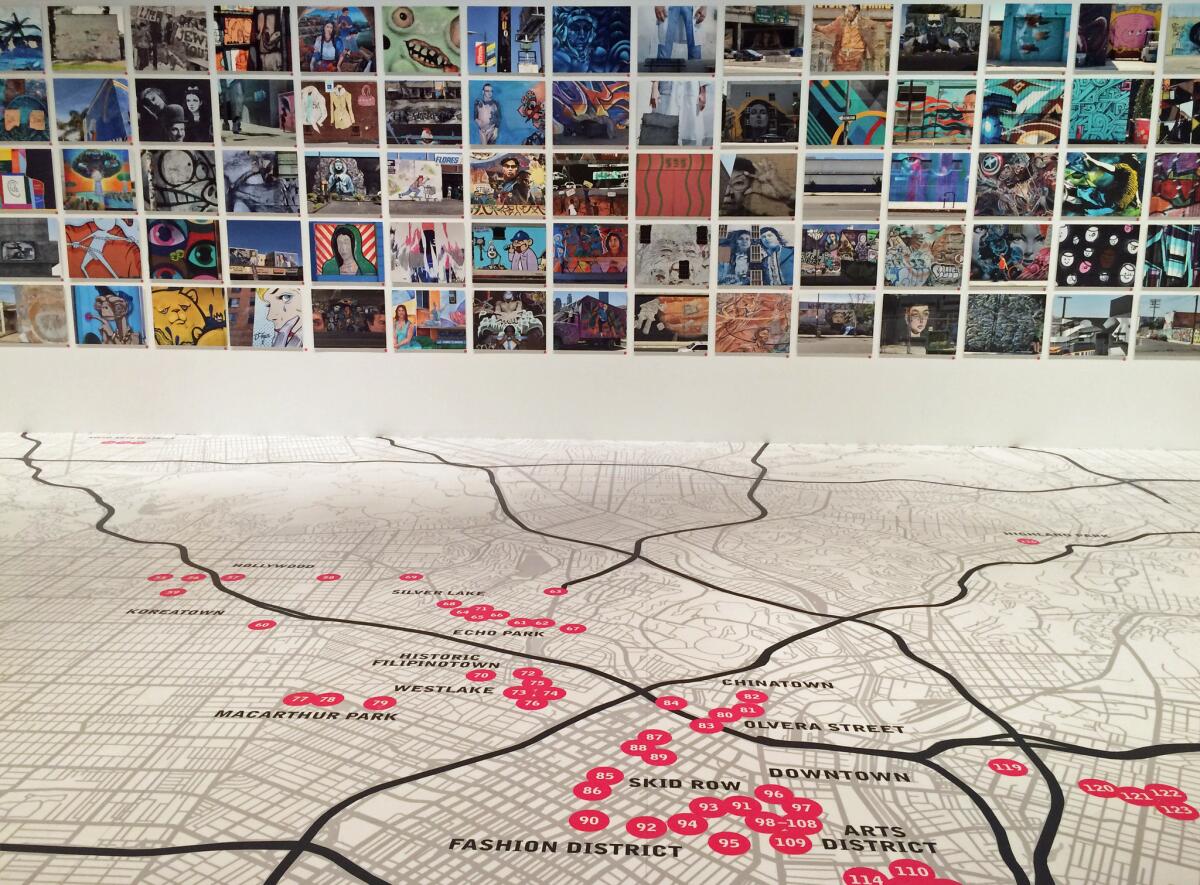

As the Guggenheim Memorial Foundation has supported California artists, so too has it supported work about California. Last year, the foundation supported a project about murals by Los Angeles artist Ken Gonzales-Day that was displayed at the Skirball Cultural Center as part of “Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA.”

The artist’s “Surface Tension” was a record of murals throughout Los Angeles — an attempt to examine the broad gamut of image-making on the city’s walls.

“One of the things that we hear a lot is the relationship between Mexican muralism and the murals of Los Angeles,” Gonzales-Day says. “The part we are less familiar with are the celebrity murals and the murals that are part of advertising and murals that are part of vernacular culture. I was trying to look at those overlaps.”

In the process, he began to consider “the city as an outdoor museum maintained by communities for communities” — one that occurs on an unprecedented scale. Says the artist: “I didn’t realize how vast it was.”

But perhaps the Guggenheim is most significant for giving artists the financial freedom to test out concepts at key moments in their careers.

Los Angeles artist Nicole Miller is known for her work in video and installation — work that employs film to explore issues of history and identity and the self. She has a video piece on view at the California African American Museum: “Athens, California” is inspired by the southern Los Angeles County community.

The fellowship, she says, will allow her to to experiment with new materials in new ways. Three years ago, the artist acquired at auction a mold of Michael Jackson’s body used for the making of the ’80s film “Moonwalker.” She aims to cast the late singer’s body in bronze at a foundry in Arizona.

“For a while, I’ve had this project in mind,” she says. “All of a sudden, it becomes a possibility.”

Feeding that sense of possibility, says Hirsch, is ultimately what the Guggenheim Memorial Foundation aims to do.

“I think we all feel there is a new kind of urgency to the work that we are doing,” he says. “The values that we support are under threat and not to be taken for granted — the values of critical thinking and independent scientific research and politically and socially motivated art working on behalf of social justice, artists working on behalf of different communities. That is all under threat.

“Even though the Guggenheim doesn’t have a political or moral agenda, this is important to us. Even though the work we are supporting isn’t overtly political, we are saying this is what we value, this is what we care about.”

For another generation of artists and thinkers, the experiments are just beginning.

The complete list of winners from Southern California:

Architecture planning and design: Edward Dimendberg

Astronomy/astrophysics: Shrinivas R. Kulkarni

European and Latin American literature: Eleanor Kaufman

Film/video: William David Caballero, Marsia Alexander-Clarke, Lee Anne Schmitt

Fine arts: Todd Gray, Lies Kraal, Dave Hullfish Bailey, Nicole Miller

General nonfiction: Roxane Gay

History of science, technology and economics: Erik Meade

Intellectual and cultural history: Stefania Tutino

Photography: Anthony Hernandez

Poetry: Amy Gerstler, Ilya Kaminsky

Religion: Nile Spencer Green

ALSO

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

UPDATES:

FOR THE RECORD

April 5, 8 a.m.: An earlier version of this story said the first class of Guggenheim Fellows consisted of men only. There was one woman, historian Violet Barbour.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.