Review: The puppet orgy is back in a triumphant reworking of ‘Young Caesar’ at Disney Hall

- Share via

Now we know.

It has been 45 years since Lou Harrison’s “Young Caesar,” an overtly gay opera for puppets with penises, had its hapless premiere in Pasadena, to the outrage of some of its sponsors. But after various unsuccessful attempts to turn it into a real opera, the Los Angeles Philharmonic finally and triumphantly did so with the work’s first professional production Tuesday night in Walt Disney Concert Hall.

L.A. Phil artist-collaborator Yuval Sharon created a new version of the opera that uses the most workable aspects of the composer’s rewrites over the years, trims about 45 minutes from the score and finds a viable dramatic structure. Sharon, in conjunction with his opera company, the Industry, mounted a fanciful, visually stunning, endearingly mercurial, marginally risqué, momentarily over-the-top and ultimately touching production. The L.A. Phil New Music Group, conducted by Marc Lowenstein in the final Green Umbrella program of the season, was sensational, revealing layer upon layer of sheer musical gorgeousness capable, from the first bars, of lifting the spirits.

“Young Caesar” can finally be heard as what Harrison’s admirers had long suspected it must be — a marvelous, uniquely American outlier opera. It is Harrison’s most ambitious work and one that he wouldn’t let go of from the time of its 1971 premiere to his death at 85 in 2003.

Unlike gay operas that came before (and have come since), [Lou] Harrison’s is not a tragic tale about the anguish of being an outsider.”

— Mark Swed

Unlike gay operas that came before (and have come since), Harrison’s is not a tragic tale about the anguish of being an outsider. The production’s creative consultant, Eva Soltes, a longtime associate of Harrison, described the composer in the preconcert talk as the proudest gay man she has ever known and the opera’s invitation into gay culture as a call for everyone to enjoy life.

Erotic amusements are certainly offered. Back in 1971, Pasadena’s putative little old ladies did not quite go for Harrison’s “eroticon,” with its flying phalluses, but “Young Caesar” is much more than that. Harrison uses pleasure for subversion. The original version was written at the height of the Vietnam War, and the opera is a potent and entirely original form of persuasion to make love not war.

Having gone through his rites of manhood in Rome, the ambitious young Julius Caesar — Gaius in the opera — is sent to Bithynia to collect ships from King Nicomedes. History is a little uncertain about this, but there is reason to believe that Nicomedes enticed Caesar into a dalliance as yet another rite of manhood.

For Harrison and his librettist, Robert Gordon, who worked with Sharon on this new version, Nicomedes dazzled the naive and uptight Gaius with opulence and sensuality. A wiser, older leader attempting to mold a young man who would one day take over the world, Nicomedes tried, and almost succeeded, in getting Gaius to slow down, to take notice of and learn from the world around him. Let love be his guide.

Gaius falls for Nicomedes, but duty prevents him from, as Nicomedes urges him to, stay. Had Nicomedes’ sensual enticements worked, Caesar might not have gone on to slaughter 1 million men in Gaul, and history might have been radically different.

Harrison was, himself, a Nicomedes who refused to deny himself an abundance of pleasures, and he put much of what he knew and loved into “Young Caesar.” That is what got him into trouble.

This began with the Gordon’s original libretto, which was long on narrative and just plain long. Harrison’s initial idea had been that the opera would be Eastern in aspect, with Asian instruments along with some homemade ones, and recitative chanting reminiscent of the Chinese opera he enjoyed going to while growing up in the Bay Area. There was much more, and over the years as the opera accrued Western instruments, a chorus and arias, it blossomed into a magnificent hybrid of East and West, with nods historically from Elizabethan music and Handel to the present. It was always thought, however great the charm, an impossible mess.

What Sharon and crew came up with, in this new, 112-minute version of two acts performed without break, is not a mess but a celebration. There is now a little bit of everything, and the crew is the key. Sharon retains something from all the versions and then adds his own glosses, giving Caesar every reason in the world to be dazzled.

One insight was to have traditional instruments dominate the first act, which takes place in Rome, while the Asian ones (most traditional Chinese) and homemade bells and the like are reserved for exotic Bithynia and exotic sex.

The opera’s narration always has been a problem, but the narrator here is another inspiration. The hilarious Bruce Vilanch, seated on a lounge chair, cocktail in hand, might have been a cross between Percy Dovetonsils (Ernie Kovacs’ outlandish impersonation of a poet on his 1950s television show) and the delightfully pleasure-loving composer.

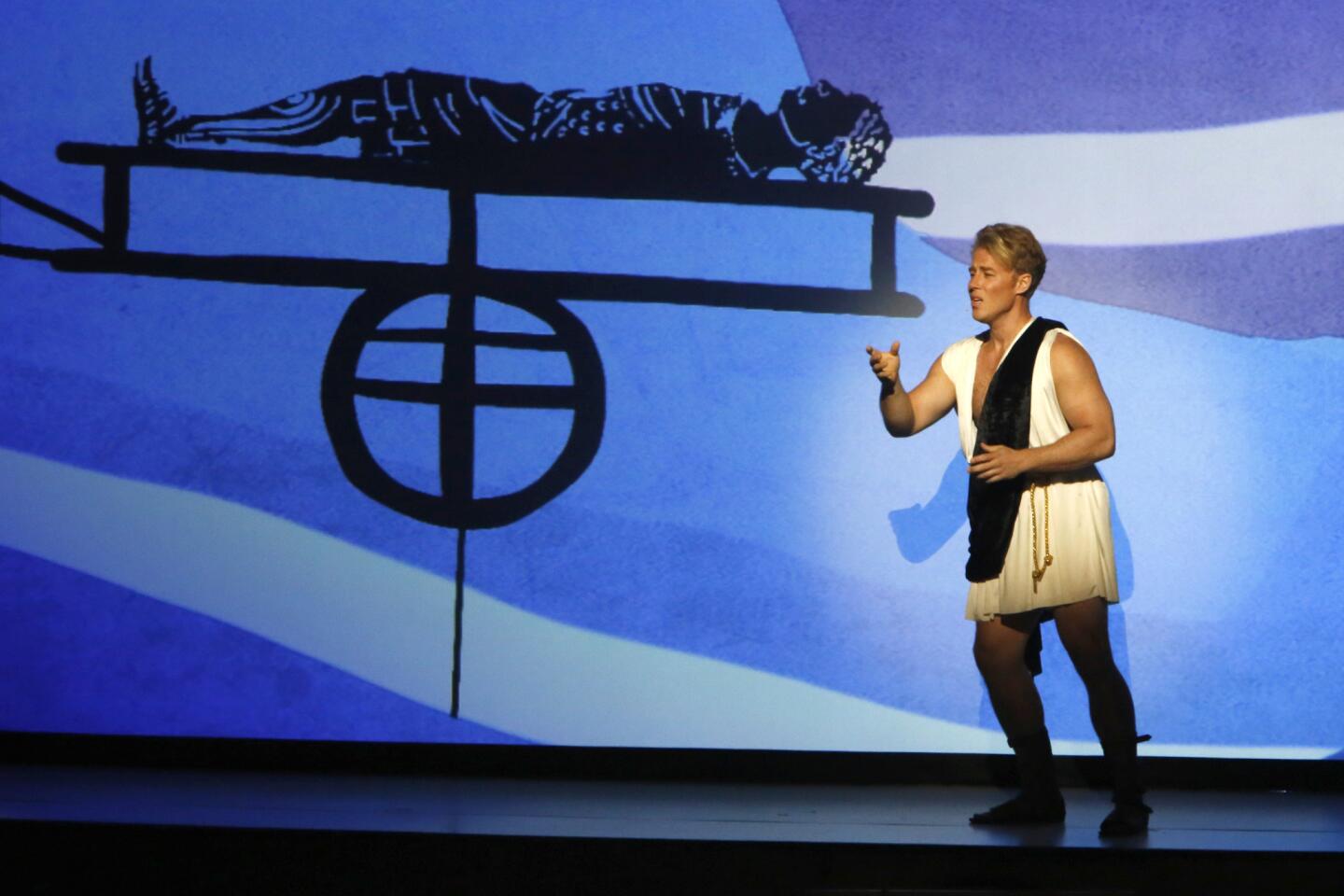

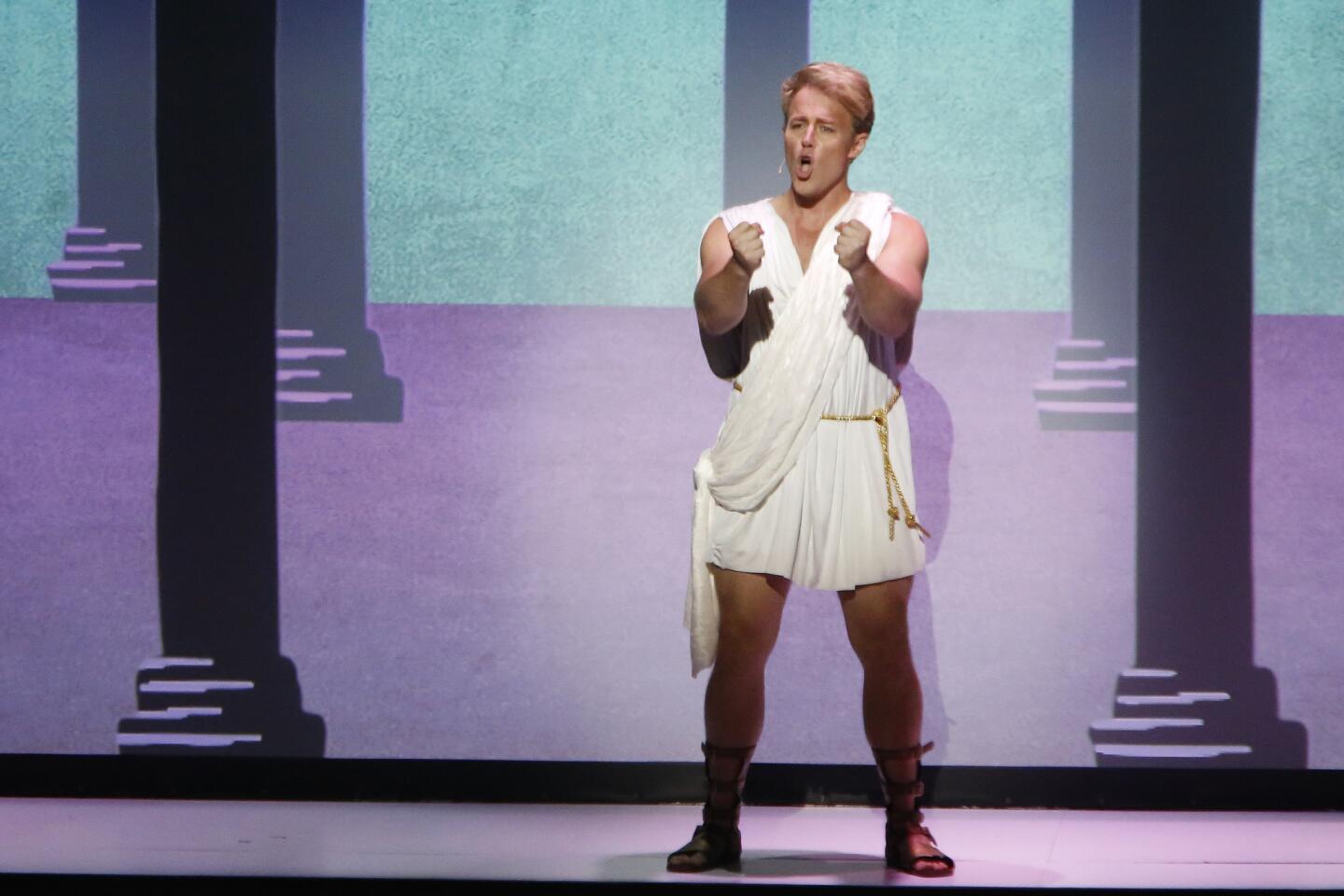

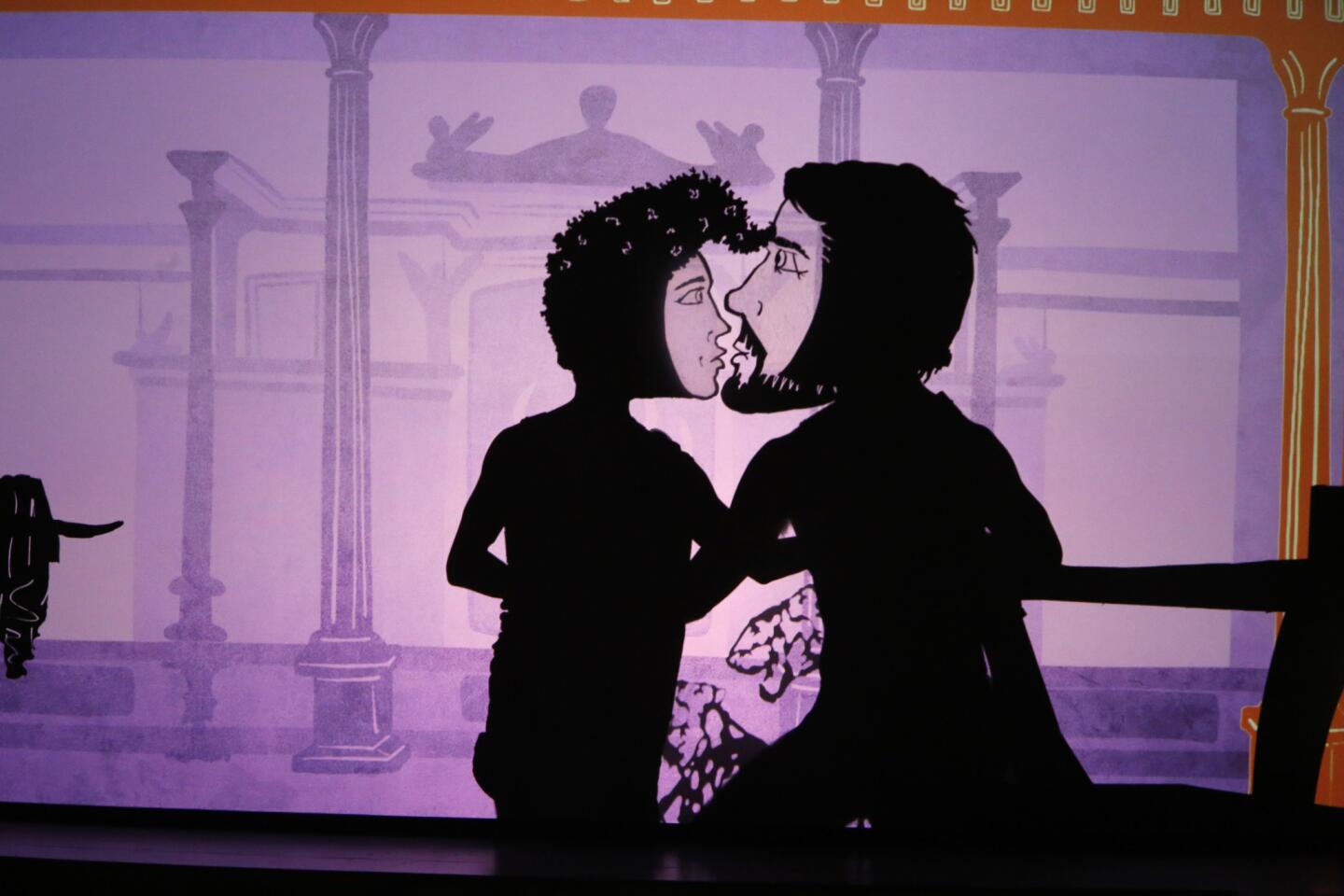

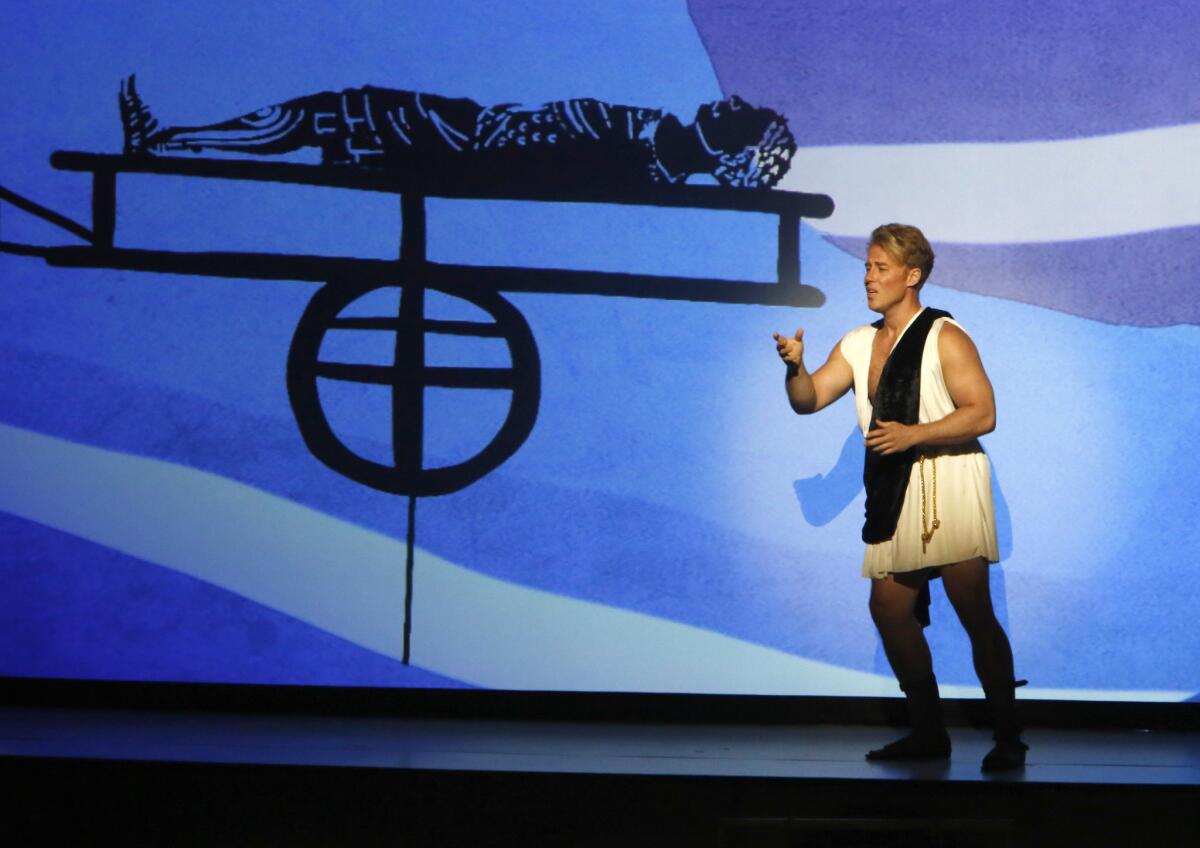

Puppetry was retained, this time shadow puppets projected behind a screen against clever animation that takes its impetus from Harrison’s own graphic illustrations. Yes, for an orgy scene, phalluses did merrily fly. A ramp surrounded the musicians for singers and dancers. The dancers were male, scantily dressed as for a gay pride parade, and choreographed with flair by Danny Dolan.

The costumes by Daniel Selon, who also designed the puppets, included goofy togas and fright wigs, but nothing so silly as to prevent moving characterizations from the singers, all of whom excelled. Adam Fisher’s Gaius touchingly flowered from gullible teenager to sensual lover to warrior. Hadleigh Adams emphasized wistful wisdom, not lechery, as Nicomedes. Nancy Maultsby (Gaius’ pushy aunt Julia), Delaram Kamareh (Gaius’ wife, Cornelia) and Timur (Gaius’ slave-boy Dionysus) brought subtle touches to their short arias.

The arias are among the glories of Harrison’s score, these brief, lyric meditations on something beautiful or meaningful in life (becoming a man, grasping a daughter, taking chances). The recitatives that had been thought to be the opera’s longueurs here were shown to be, in fact, as subtly inflected as Gregorian chant.

But it is the orchestra that holds the greatest glories of all. Harrison had as much a genius for processionals and dances as he did for haunting introspection, and he took full advantage of his wondrous collection of instruments. Trumpets and percussion thrilled. Harp and violin and flute solos produced moments of delicious intimacy. An upright piano with tacks on its strings did not sound barrel-house tacky but mysterious. The instrumental colors never stopped changing.

If all of this seems an extravagance for one performance, it was an extravagance of necessity. If you weren’t there you missed it. But this was exactly what will get the word out.

Someone will pick up the production. Others will do the opera. And they’ll know to do it because the performance was recorded live for digital release, probably early next year.

“Young Caesar” lives.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.