Review: Yoko Ono gets a remarkable tribute from a new generation of sisterhood

- Share via

Friday a little after 10 p.m., Walt Disney Concert Hall once more became the site of a history-making moment. Thanks to the participation of 75 remarkable women, after several unreasonable decades, Yoko Ono was a sphinx no more.

That she is an icon of the art world has not been in question for some time. As the avant-garde, outrage-intensive Fluxus movement of the early 1960s has achieved top-museum-level credibility, her reputation as an innovative and effective visual, conceptual and performance artist has greatly grown.

But where Ono has never gotten respect is as a musician, even though music has been very much at the core of who she is as a conceptualist, as a performance artist and, lastly, as a pop figure. It was pretty much the last, Ono the songwriter, who was the charge of “Breathewatchlistentouch,” the latest in the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s season-long Fluxus Festival, given even though the concert had no need for the orchestra and Fluxus almost seemed an afterthought.

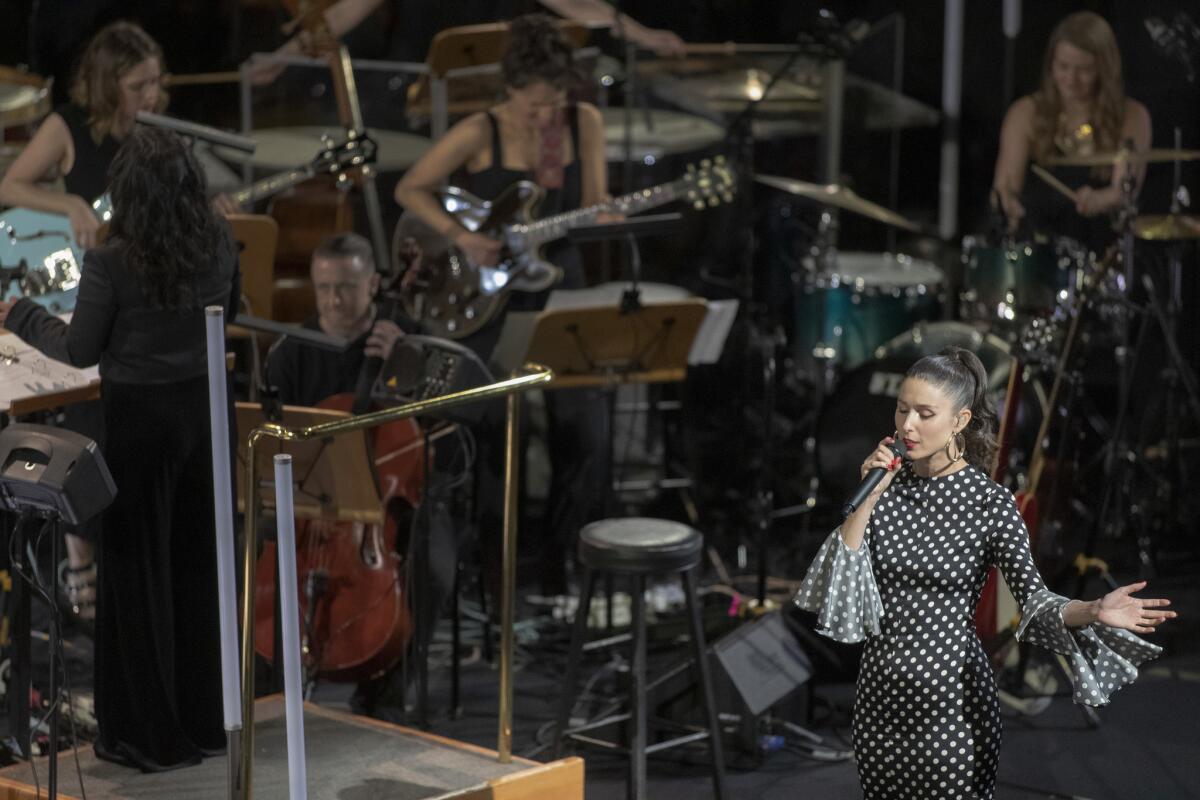

Rather, this was mainly a pop concert, highlighting pop singers, along with a backup chorus, band and dancers. All — but for a violinist, a handful of dancers and most of the stagehands, were women. Although the festival has been a partnership with the Getty Research Institute, it this time also had the contribution of Girlschool L.A., a community of women-identified artists founded by Airborne Toxic Event violinist Anna Bulbrook, who was the producer and mastermind of the concert.

YOUTH SYMPHONY: Conductor pledges 50% of all new music he plays will be written by women »

First off, nearly all of this was unexpected, which is partly why it mattered as much as it did. The program notes focused on Ono’s background as a Fluxus artist. She was a classically trained musician who had been married in the late 1950s to Toshi Ichiyanagi, now the dean of Japanese composers. She jump-started the SoHo art scene in 1960 by presenting loft concerts curated by composer La Monte Young. She interacted with the likes of composer John Cage and pianist David Tudor.

But she remained mainly on the fringes until her marriage to John Lennon in 1969 and her entree into pop culture and pop music. In all this, she continued to take to heart Cage’s belief that people were capable of changing their minds, that that’s all it would take to make the world better, instructing people to listen, remain silent, choose peace over war. Her message was that it’s easy.

Known for a presence that was quiet but impactful, she would, for example, stage a night event at a Kyoto temple and ask people to touch one another in the darkness. Yet she seemed to somehow have turned shrill. For Ono, screaming was always the flip side of the silent coin. As a pop singer, her wailing voice was put to a driving beat, commonplace melodies and harmonies, weirdly inconsistent song structures and lyrics full of New Age sentiments and personal emotions, giving the impression of an overindulgent Fluxus gone haywire.

The function of the Disney Hall concert was to rectify all this. One focus was on Ono as a pioneering feminist, which she has been. But the lesson we learned long ago about Ono is that as soon as you try to pigeonhole her, you are in trouble. Her greatness is the big picture. (I hope someone has a major biography in the works.) An all-female lineup might then have felt exclusionary and antiquated, reminiscent of, say, the Women’s Symphony Orchestra of Los Angeles nearly a century ago, when women weren’t allowed in the L.A. Phil.

Bulbrook, though, had the goods. She selected singers who, each in her own engaging way, demonstrated Ono’s songs to have a previously unsuspected versatility. Ono’s way of performing them is not the only way. The words do matter. There is a musical freedom that is implied, but no one has ever attempted to find it in such a way. The chorus and orchestra happened to be terrific. Disney’s resources were embraced, including the spectacular organ. Percussion was a highlight, but so too were great keyboard and sax solos.

Shruti Kumar conducted impressively, creating striking arrangements that served each very different singer. Dress, as you might expect, was never an afterthought on anyone’s part.

The songs came primarily from Ono’s albums from the 1970s and on. First up was Miya Folick cheerfully singing, and meaning it, “Soul Got Out of the Box,” and it never got put back in again. La Marisoul (Marisol Hernandez) brought a Latin soul to “Born in a Prison.” Afro-pop came courtesy of the Sudan Archives. We Are King was urban.

Shirley Manson, Amber Coffman and Francisca Valenzuela offered a more conventional pop spin on Ono songs, and that too was a revelation as they respectively underscored the want to be happy in “Nobody Sees Me Like You Do,” counted the stars and felt the upbeat breeze in “Run Run Run” and fueled the feminist anthem “Sisters, O Sisters.”

SPRING PICKS: Our critic’s guide to the season’s most promising performances »

There was the obligatory nod to Fluxus, performance works from Ono’s collections “Grapefruit” and “Acorn,” but this also was given a pop context. Instructional dance pieces had modern choreography from Nina McNeely. Madame Gandhi perkily read a couple of Ono’s powerful environmental “Life Pieces,” in one asking us to imagine ourselves as an embryo and wondering whether we would still want to come out in the world we now know. St. Vincent went off color when she added to Ono’s “Cleaning Pieces” some sexual rejoinders courtesy of composer Nico Muhly. Kamil Oshundara was the one to gently ask us if we might not want to touch someone (but it wasn’t required).

It had not been known in advance whether Ono, 86, would appear. In what might have been her final sphinx moment, she entered and exited in a wheelchair under the cover of darkness. But in between, she could be seen in her broad black hat clapping to the beat. By the end, the performers simply couldn’t not acknowledge her, and the audience was asked to join a performance of “Imagine,” which she co-wrote with Lennon.

By this point, it was obvious that we no longer needed to imagine her or “a brotherhood of man,” which had become a sisterhood of everyone, and the last step in the iconification of Ono. I’m glad she was there to witness it.

HOLLYWOOD BOWL: Win Ray Chen’s contest and you could play onstage »

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.