‘Hamilton’ costume designer on how he streamlined 18th century looks for a 21st century show

- Share via

One of the few directives that Lin-Manuel Miranda gave to designer Paul Tazewell about his costume for Alexander Hamilton was that he be represented in green — because “green is the color of money” and thus appropriate for the first secretary of the Treasury.

And indeed, Miranda appears in the second act of “Hamilton” — the acclaimed hit minting money on Broadway and expected to dominate the Tony Awards on Sunday — in an ostentatiously shiny, silk green coat in the style of the 18th century.

But far more influential as an inspiration for Tazewell was the simple ski cap worn by one of the actors during the rehearsals prior to the show’s first readings at the Public Theater in 2014. Okieriete “Oak” Onaodowan, playing the dual roles of the tailor Hercules Mulligan and James Madison, would show up in a ski cap to ward off the early-year chill.

“It seemed so connected to who Oak was as an actor, and I also thought that it connected him to Mulligan because it could live both in the 18th century and in the contemporary world,” recalled Tazewell, who earned one of the 16 record-breaking Tony nominations for the show. “It gave him, as a tailor interested in clothes, a youthful, playful and more theatrical up-to-the-minute quality. So I thought it was a smart choice to incorporate that kind of thing in order to bridge the gap between their world and ours.”

The ski cap was just one detail in myriad images that Tazewell said he “mixed into the pot” upon teaming up with Miranda and director Tommy Kail, with whom he’d previously worked for the Tony-winning musical “In the Heights.” Having designed period (“Doctor Zhivago”) and contemporary (“Bring in ’da Noise, Bring in ’da Funk”) costumes, Tazewell approached the assignment with one primary goal.

“In order for it to resonate as strongly as possible, I thought it was important to get beyond our preconceived notions of these iconic figures while honoring how Lin had brought the story to light,” he said, referring to “Hamilton” in all its multicultural, hip-hop glory.

To that end, he researched the 18th century paintings of John Trumbull as well as the mash-up fashions of Alexander McQueen, John Galliano and Jean Paul Gaultier and the satiric portraits of Kehinde Wiley, who depicted men and women of color in re-creations of classic portraits.

The first eureka came through the budget limitations imposed by the Public Theater readings. To show the first audiences how the two eras would meet in the look of the show, Tazewell started with a simple parchment-toned silhouette of vest, breeches and boots that then gave way to the blue coats, red trim and brass buttons of Washington’s Continental Army. Most important, no wigs.

The success of the workshop resulted in two guiding principles: First, period from the neck down and modern from the neck up; and second, strip away all the embroidered detail of the 18th century so the audience could move past the distraction of artifice to the story itself.

Actors of color inhabiting the costumes of their ancestors’ oppressors provided a powerful and paradoxical subtext.

“We discovered that the clothes lay very comfortably on the actors,” he said. “They could relate to the costumes in a very contemporary way with a street exuberance and the beauty of contemporary face and hair. It also informed how they were playing the roles.”

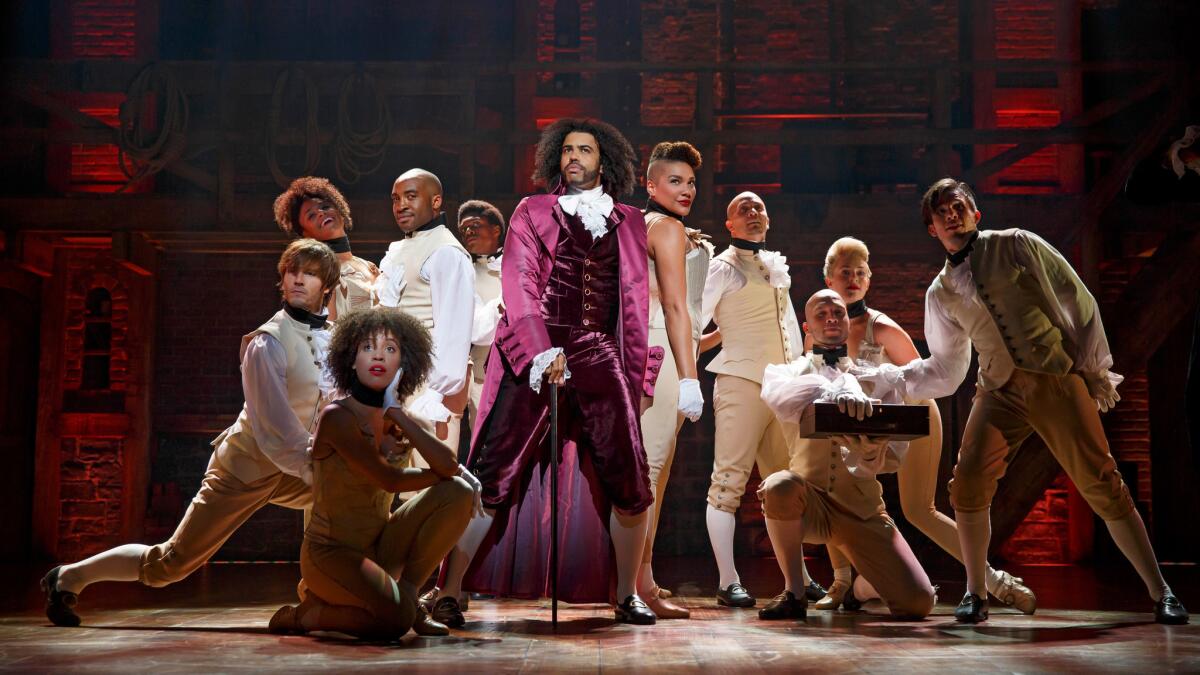

Case in point, Daveed Diggs’ galvanic dual performance of the Marquis de Lafayette and Thomas Jefferson.

“Daveed’s own personal style, all that hair, his very lean and tall body, reflected how we would dress him,” the designer said. “We wanted to take advantage of that and what came together was a realized version of Jefferson, the politician as a rock ’n’ roll star.”

As for Hamilton, wife Eliza Schuyler and sister-in-law Angelica Schuyler, Tazewell said he traced their respective emotional arcs in color. He dressed Hamilton, the ambitious immigrant, in the neutral tones that yielded to more ornate looks after his successes in battle and politics and that ended in the somber, dark hues of tragedy. He dressed Phillipa Soo, as the long-suffering Eliza, in sympathetic ice-blue. Her smart, dynamic sister, played by Reneé Elise Goldsberry, wears solar hues.

The costumes demanded versatility, not just to execute the kinetic movement of choreographer Andy Blankenbuehler but also to allow lightning-quick changes. Actors move from the boots, breeches and sleeveless vests — inspired, Tazewell said, by the muscular arms of the cast — to full military dress and, in the case of the women, to ballroom gowns and back to the simple, parchment-toned silhouettes of the beginning.

Throughout the whole design process, the smartest thing for Tazewell to do was simply to “get out of the way,” stripping things down so that his work could “breathe more.”

“Ultimately, I can only finally judge by how I feel about something. It’s an intuitive and emotional response to what I see,” he said. “That’s what I trust.”

Follow The Times’ arts team @culturemonster.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.