Review: ‘@Large: Ai Weiwei on Alcatraz’ a powerful meditation on repression

- Share via

Reporting from ALCATRAZ — Ilham Tohti, an economist and writer at Minzu University in Beijing, hosted the website Uighur Online, meant to encourage understanding between Han Chinese and ethnic Uighurs in the sprawling but remote northwestern region between Mongolia and Kazakhstan. The Chinese government shut down his website in 2008, later detaining him for questioning about supposed ties to extremists.

Rearrested in January, Tohti, 44, last week underwent a rapid two-day trial. On Tuesday, he was sentenced to life in prison. The court’s ruling shocks the moral consciousness, even if it is unsurprising to international monitors of human rights.

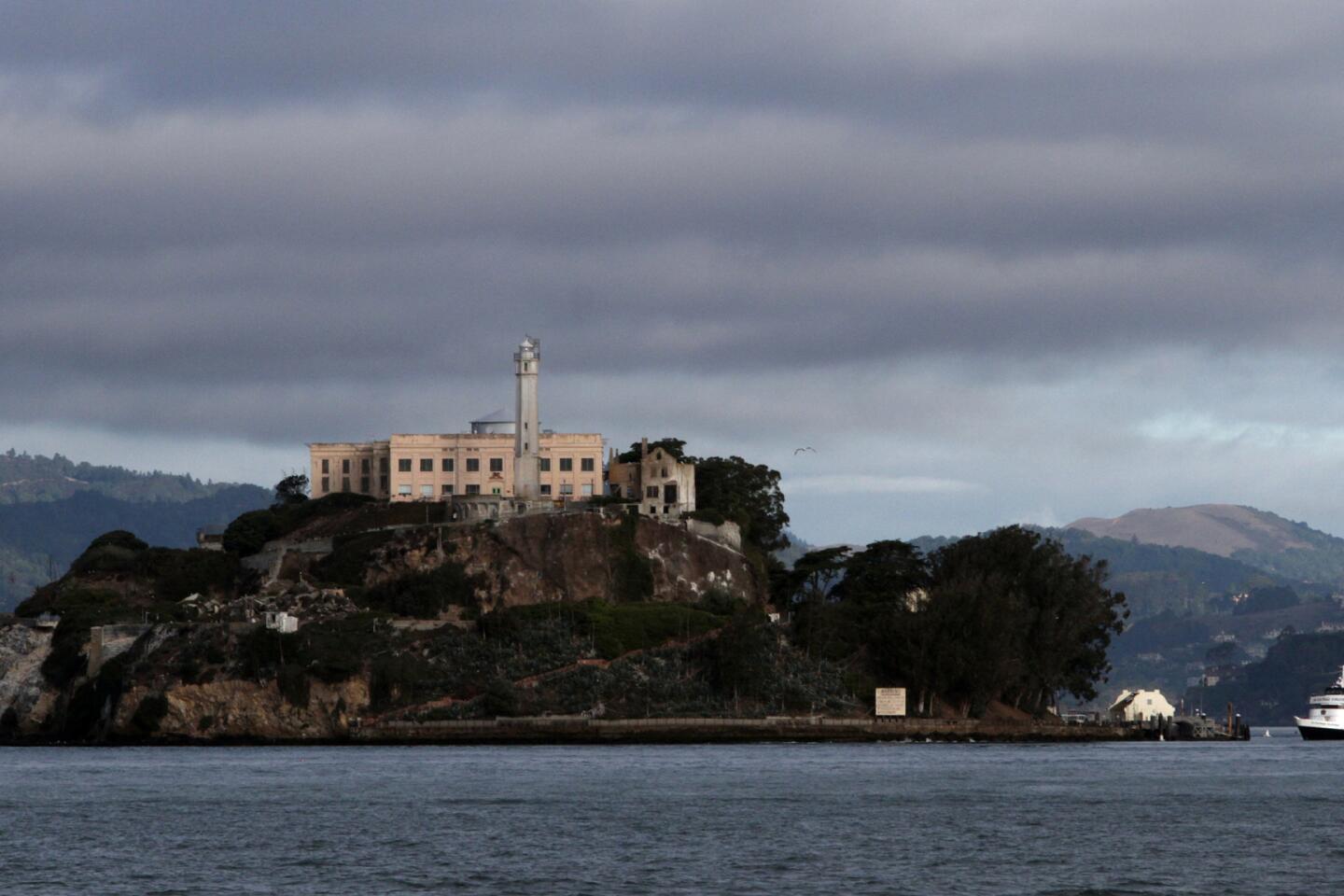

A close-up portrait of Tohti’s face today looks up from the floor of the New Industries Building at Alcatraz, once a notorious federal prison in the bay north of San Francisco and now one of America’s most-visited national parks. The portrait is part of a site-specific installation — one of seven — by artist Ai Weiwei, in an unprecedented exhibition opening Sept. 27 for a seven-month run.

Ai, not unlike Tohti, has himself been detained by the Chinese government. His passport has been withheld for three years.

“@Large: Ai Weiwei on Alcatraz” is an always-poignant, often-powerful meditation on soul-deadening repressions of human thought and feeling. The phenomenon is ancient, but here it is inflected by the dizzying terms of our still-new Digital Age. A grim but world-famous site for convicts has been reimagined as a space for comprehending prisoners of conscience within the modern surveillance state.

Ai is uniquely suited to the task, for reasons of artistic as well as personal political history. His work braids two prominent strands of art in the last 50 years.

One is the intellectual heft of Conceptual art, with its complex inquiries into the tangled underbrush of modern social life. The other is Pop art, a double-edged sword that enforces conformity through the inescapable personal pleasures of popular appeal. For a visitor, “@Large” ricochets between enchantment and alarm.

Tohti’s image is among 176 similarly colorful portraits of imprisoned dissidents that carpet the floor. Borrowing published photographs, the high-contrast black and white draws on Andy Warhol’s Pop art style.

Ai then shadowed the face in bright blue — the color of the flag adopted nearly a century ago by a short-lived Uighur independence movement. Tohti is the face of a people.

The vast portrait field was constructed from Ai’s designs by volunteers using more than a million tiny Lego bricks. Such a labor-intensive process is appropriate to Alcatraz’s New Industries Building.

As part of a penal modernization plan in the mid-1930s, the now-crumbling space is where well-behaved prisoners were allowed to work for money by sewing uniforms or reconditioning furniture. For highly individual portraits, the uniformity of Lego bricks, each like all the rest, hums with the subtle undertone of being a model prisoner.

The exhibition sprawls through ruined rooms in four sections of rocky Alcatraz. It was organized (and funded) through the herculean effort of the local For-Site Foundation and its executive director, art dealer Cheryl Haines, in partnership with the National Park Service.

Two nature motifs — birds and flowers — recur. Birds signal freedom, while also evoking the island’s name. (It derives from alcatraces, a Spanish word for a relative of the pelican). Flowers are symbols of remembrance.

The two come together in a surprisingly effective way near the end of the show, where wooden racks in an old dining hall hold free postcards featuring pictures of exotic birds or brightly colored blossoms. Visitors are encouraged to take one. After all, isn’t that what is routinely done when leaving a tourist site?

Ai then gives a twist to the common experience: Every postcard is pre-addressed to a prison somewhere around the world. Feel free to snail-mail your thoughts.

Birds are also found in the first room, where avian paper kites are suspended from the ceiling around a big, elaborate Chinese dragon made from smaller kites. Ai has worked quotations about human rights into the hand-painted designs — his own assertion that “Every one of us is a potential convict,” Edward Snowden’s that “Privacy is a function of liberty,” and more.

Locked indoors, the hundred bird-kites cannot fly.

The most potent bird, however, is hidden deep within the building’s bowels. It can be glimpsed only through barred and broken windows along a narrow catwalk once used for surveillance by armed guards.

“Refraction” is a mammoth, 5-ton metal wing that looks like prehistoric bones from a natural history museum. It was built from the parabolic reflective panels of Tibetan solar cookers.

The great, undulating solar wing is festooned with tea kettles, woks and frying pans. Yet none of these tools has any nourishing use, since the colossal wing is imprisoned within stifling gloominess away from the life-sustaining sun.

Or, has it fallen like Icarus, victim of complacency and hubris? Ai transforms Alcatraz into a museum for display of a way of life made impossible.

Upstairs in the grim prison hospital, he has filled the cells’ grungy porcelain toilets, sinks and bathtubs with mounds of little white porcelain flowers. On one hand kitschy decoration, like Capodimonte knockoffs of refined Meissen floral porcelains — themselves inspired by great Chinese models — Ai’s bouquets also offer genuine respect for the deep human suffering that still reverberates through these tattered rooms.

No sentimental view of prison life is offered either, although the artist seems aware of that danger. The flower installation oozes a delicate but defiant autobiographical dimension.

Inevitably, the floral profusion recalls “let a hundred flowers bloom,” Mao’s 1956 invitation to Chinese intellectuals to offer critical advice to the Communist state. Inundated with voluble dissent (including from Ai’s poet-father), the dictator quickly pulled the plug — but not soon enough to prevent the blossoming of one specific flower: Ai Weiwei was born just days after Mao began his 1957 crackdown on those dissidents.

Nor is American history exempted from scrutiny. Each of a dozen tiny rooms in Cell Block A, none so large that a visitor can fully spread his arms wide, holds a single metal stool. Sit and listen to poetry and music by people once imprisoned for their beliefs, from civil rights icon Martin Luther King Jr. to Russian punkers Pussy Riot.

Again the site resonates: Cell Block A is where scores of American citizens who were conscientious objectors to World War I were imprisoned by our own government.

The sound installation is one of two in the show, the other consisting of recorded chants by Buddhist monks and Hopi dancers played within cramped psychiatric observation cells. The role of chanting as a restorative spiritual balm against the indignities of daily strife internalizes the struggle of freedom and imprisonment within the individual body and mind.

If there’s a shared weakness to the pair of sound installations, it’s that audio works require a degree of quiet solitude that a busy public tourist site cannot provide. Even on a less crowded preview day, the works’ impact was muffled.

That may be a simple function of one of the more astounding facts of Ai’s otherwise indelible achievement here: Because of his own shackling by Chinese authorities, he has never set foot on Alcatraz.

Everything was, instead, designed and executed through photographs, research documents, videos, maps, plans, Skype conferences and scores of assistants, many of whom traveled from Beijing to San Francisco as Ai’s surrogate eyes and ears. There’s finally something lovely about the mix of independent determination and mutual need.

At the site, the grim, hulking reality of the prison stands in starkest contrast to the wide-open natural beauty of the surroundings. Exit any building where Ai’s carefully conceived and physically constrained birds, flowers and human voices reside, and you’re immediately struck by the gorgeous open sea, sky and hillsides rising across the bay.

That opposition is critical to the exhibition’s success, as Ai surely knew. One can only wonder what this exceptional artist might have done had he been there to see it.

Twitter: @KnightLAT

------------

‘@ Large: Ai Weiwei on Alcatraz’

Where: Alcatraz Island, San Francisco Bay

When: Sept. 27-April 26

Tickets: Free with purchase of Alcatraz Cruises tickets to the island: Adults and children ages 12 and older $30; children ages 5 to 11, $18.25; seniors 62 and older, $28.25; family (two adults and two children), $90.25; children 4 and younger, free.

Info: www.for-site.org. and alcatrazcruises.com.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.