Critic’s Notebook: L.A. County Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky exiting as a champion of arts

- Share via

After passing through tight security and walking into the downtown office of Los Angeles County Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, the first thing that welcomes a visitor is agreeable art, paintings on loan from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

A tall plant blithely blocks a good portion of an abstract still life. I mention this to a Yaroslavsky staffer, who laughs and nonchalantly pulls the plant somewhat, but not completely, out of the way.

The five-term supervisor, who will leave office at the end of year because of term limits, has been singularly fearless among U.S. politicians as an arts advocate.

For Yaroslavsky, art is not something to be fussed over but simply a vital part of everyday life, be it civic or domestic. A fine painting and a nice houseplant need not fight for attention; there is room for both.

Even so, while most politicians continue to operate on the principle that the arts are something to be avoided, Yaroslavsky — whose 3rd District includes the Westside, Hollywood, Beverly Hills, Malibu and the San Fernando Valley — describes himself as having been, during his two decades as supervisor, on the opposite mission.

“I guarantee you I’m the only politician in California that starts a stump speech before community groups with three things I want to talk about,” Yaroslavsky proudly notes during a recent conversation, “and one of them is arts and culture.” The others are “fiscal integrity of the public sector, especially in the county where I serve, and transportation.”

In saying this, Yaroslavsky may also be the only politician who actually underestimates himself. It would be hard to find another major politician anywhere in the entire country with Yaroslavsky’s record for outright arts support and achievement.

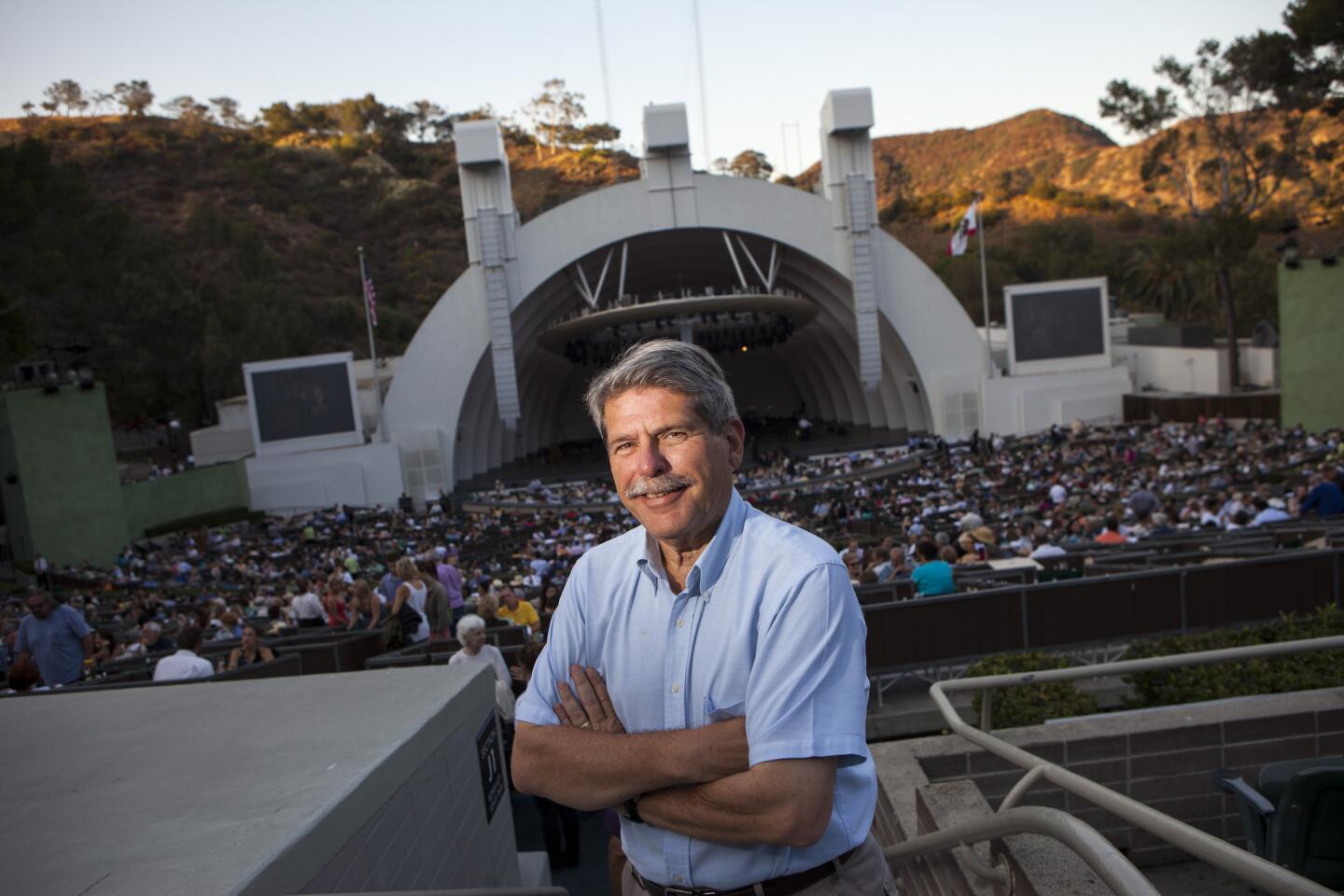

He played a crucial role in getting Walt Disney Concert Hall built. His office put more than $70 million of county money into upgrading the Hollywood Bowl with a new shell, high-tech audio and video equipment and upgraded infrastructure. He has championed past and current expansion projects at LACMA and the recent renovation of the Natural History Museum and invested $2 million of county money into the Valley Performing Arts Center in Northridge, even though that was a California State University project. The Los Angeles Philharmonic and Los Angeles Opera broadcasts on KUSC are paid for out of Yaroslavsky’s discretionary budget.

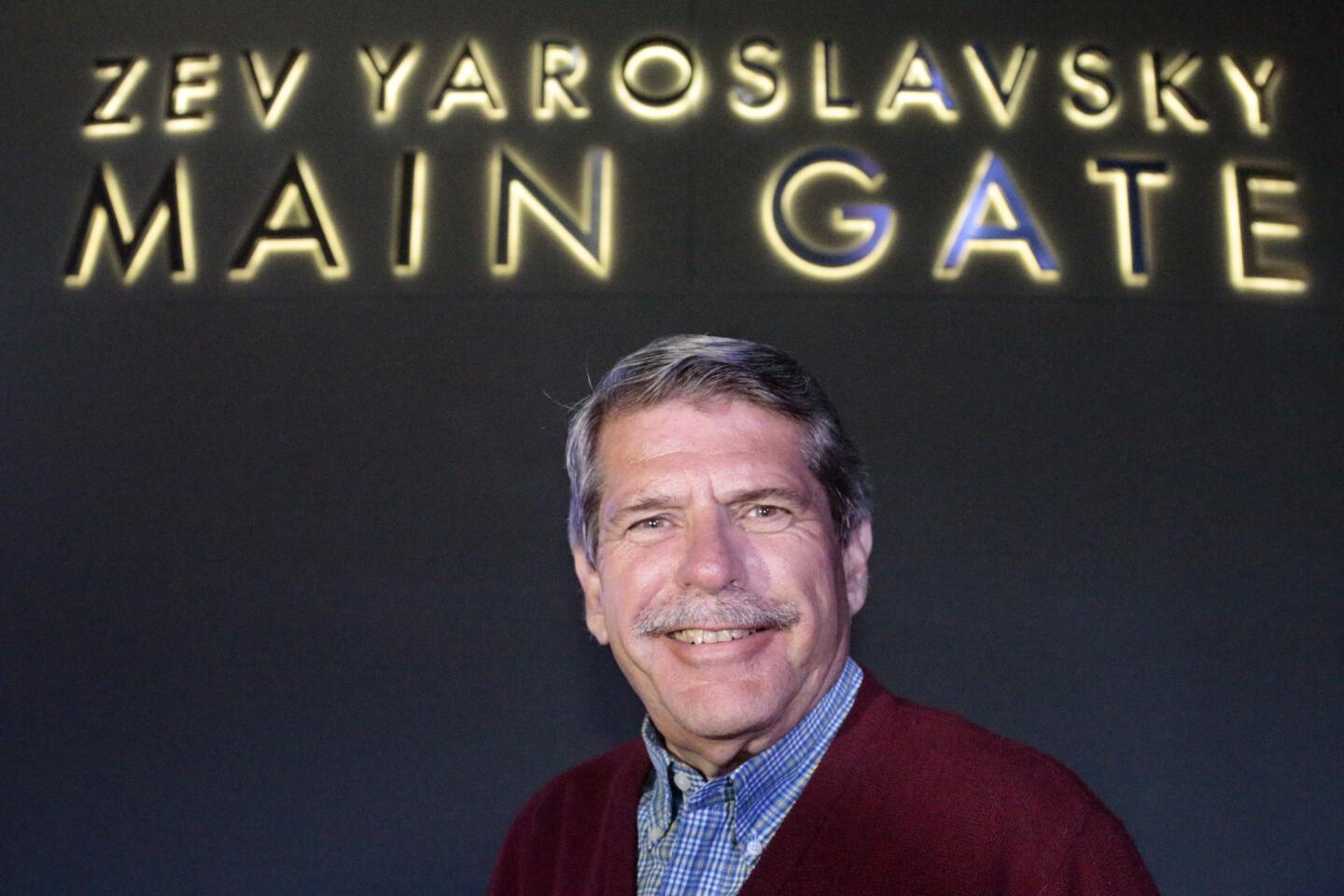

In gratitude for his arts advocacy, the L.A. Phil this summer named the Hollywood Bowl main gate after Yaroslavsky. It has been informally dubbed the Great Gate of Zev, in an allusion to “The Great Gate of Kiev,” the magisterial finale of Mussorgsky’s “Pictures at an Exhibition,” and to Yaroslavsky’s Ukrainian heritage.

“I believe that the arts are a very important part of this town,” Yaroslavsky says he preaches everywhere he goes. “Just recognize that there’s a big green dollar sign associated with the arts, which employ more people in Southern California than the defense industry does.

“And if you look ahead 50 years,” he asks, “what is going to drive our economy? Manufacturing in Southern California is history. Big corporate headquarters are history in this town. So what’s the future? The arts are explosive, proliferating like bunny rabbits all over Southern California. People who want to be on the cutting edge in whatever medium of art they’re involved in come here.”

The logical conclusion to all this growth in the arts is every politician’s manna: more jobs.

So why isn’t this a common economic mantra? Why do politicians so frequently flee involvement with the arts?

Yaroslavsky suggests that this is a crisis in leadership and not even very good politics. “I believe in my heart of hearts that if the president would make this an issue through his pronouncements and through his example, he would not have to spend any serious political capital on it. Just by elevating the issue, people would say, ‘Yeah, that makes sense.’”

In his own case as supervisor, Yaroslavsky says that supporting the arts is all upside.

“You build a bus way,” he explains, “and you’ve got half of the people in the Valley angry with you thinking you’re going to ruin their neighborhood — which is not true! You build a subway, you get people making all kinds of allegations. When you’re dealing with criminal justice, you can alienate the United States Justice Department. But when you fund the opera, when you fund the Hollywood Bowl, everybody’s happy.”

It’s not, of course, quite that simple. The economic benefit of the arts was a mantra of Rocco Landesman, the personable chairman for the National Endowment of the Arts for President Obama’s first term. He continually pointed out that every tax dollar spent on the arts was returned many fold. Yet that barely resonated in our national consciousness, and certainly not in Congress, where support for the arts seems like it is at an all-time low.

Yaroslavsky’s success as straight-talking arts leader who has been able to work with the contentious group of powerful supervisors (sometimes called the five little kings) has been not merely to rely on that kind of financial reasoning. An economic spiel is that of a politician speaking, and economics are always cause for dispute, despite the statistics.

But when the 65-year-old supervisor gives his arts spiel, he is the man speaking. He’s seen what the arts gave him and what the arts can do for society.

Having grown up in a Los Angeles household where the arts were important, and having played oboe (badly, he admits) in high school, Yaroslavsky was all but destined to take on the mantle of his 3rd District predecessor, Edmund D. Edelman, a genial amateur cellist, who was much admired for his championing of the arts.

But having first served for 20 years on the Los Angeles City Council, Yaroslavsky had little experience with the arts as public policy. It is the county historically, not city government, that is responsible for most of the major public arts resources in the region. The county owns and operates the Music Center, the Hollywood Bowl, LACMA, the John Anson Ford Theatres and the Natural History Museum.

Yaroslavsky’s first test came quickly and was a trial by fire. At the time he took office in 1995, the decade-long fundraising for Walt Disney Concert Hall had stalled. Meanwhile, the county had spent $100 million to build the parking garage underneath it with the understanding that the private sector would find the money for the hall. With a garage but no hall, the county was paying off its debt at the rate of around $9 million a year but getting no income.

“The county administrative officer came into my office,” Yaroslavsky recalls, “and announced she was ready to kill the project.

“I said, ‘We can’t walk from this,’” he says. “It would have been like hoisting the white flag of surrender to the riots, the recession, the floods and the fires. Everything had gone wrong from 1992 to 1995. It was just a mess, and the city was in a funk. It had lost its self-confidence.”

So at Yaroslavsky’s insistence, the county continued to push for the hall to be built, giving fundraisers enough time to mount a new and finally successful campaign.

“When you have a kid who can’t blow an A,” Yaroslavsky quipped during the unveiling ceremony of his “Great Gate,” recalling his days in his school orchestra, “he might nevertheless one day be sitting in a chair where he doesn’t pull the plug.”

Returning to those days at Fairfax High School, Yaroslavsky also says that our greatest arts crisis is education. A math and science major, he admits he can’t remember a single trigonometry equation, whereas he’s never forgotten Mozart’s “A Little Night Music.”

“We’re one of the few so-called advanced societies that haven’t made arts and culture a national priority,” he says, pointing to countries with a fraction of our GDP, such as Venezuela, with its $100-million El Sistema music education program.

“Aside from educating kids to the various art forms, which is self-evident as an objective, it builds self-esteem. If you become an oboe player or a violinist, if you’re painting, if you’re dancing, that focuses you in a direction constructive not only for the present but for your future.”

In the end, Yaroslavsky suggests that all it would really take for government to support the arts is for us to change our minds.

“The conventional wisdom has been that the arts are frivolous, that they’re tangential to what’s important in society,” he says. “But I’m leaving office convinced that most of us in politics don’t give our constituents enough credit for how smart they are — and, by the way, I don’t think the press gives them enough credit either. Good policy is good politics, and the support of the arts is good policy.

“It’s never been a political liability to be an advocate of the arts. People appreciate the arts, and even people who don’t appreciate a certain kind of art still recognize that the arts are an asset for the community.”

This was, Yaroslavsky says, why he never hesitated in urging the county to guarantee a $30-million loan to L.A. Opera during the recession. “We could have lost the opera, and every sophisticated city has an opera,” he says. “Plus, it didn’t cost the county a penny.”

The county’s vote of confidence in L.A. Opera, in fact, helped the company’s ability to raise the funds to pay off the loan in full and on time. “I think if you treat the public as adults,” Yaroslavsky asserts, “it will reciprocate.”

The main obstacle to achieving a broader appreciation of the arts’ role in society, as Yaroslavsky sees it, though, is that to build a constituency you need to have a discussion, and having a public discussion has gotten hard, if not altogether impossible.

“When I first got into politics 40 years ago,” Yaroslavsky, elected to the Los Angeles City Council while in his 20s, recalls, “I was called the master of the 30-second sound bite. A few years ago, I timed the average sound bite on KNX radio, and it was seven seconds.

“If you don’t say something in seven seconds, you don’t get on the radio. And if you limit yourself to seven seconds, what is the point of being on the radio, because you can’t say anything in seven seconds?”

With everything in life is being condensed, Yaroslavsky points to art as an antidote. “There is no Reader’s Digest version of life or Beethoven’s Fifth,” he jokes. “You’ve got to go through a museum at your own pace.

“It may be a challenge in the Twitter era to sit through a five-hour opera. But there is something to be said for it.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.