A dean of Japanese music talks boundaries, John Cage and life with Yoko Ono

Japanese composer Toshi Ichiyanagi is little known in U.S.

- Share via

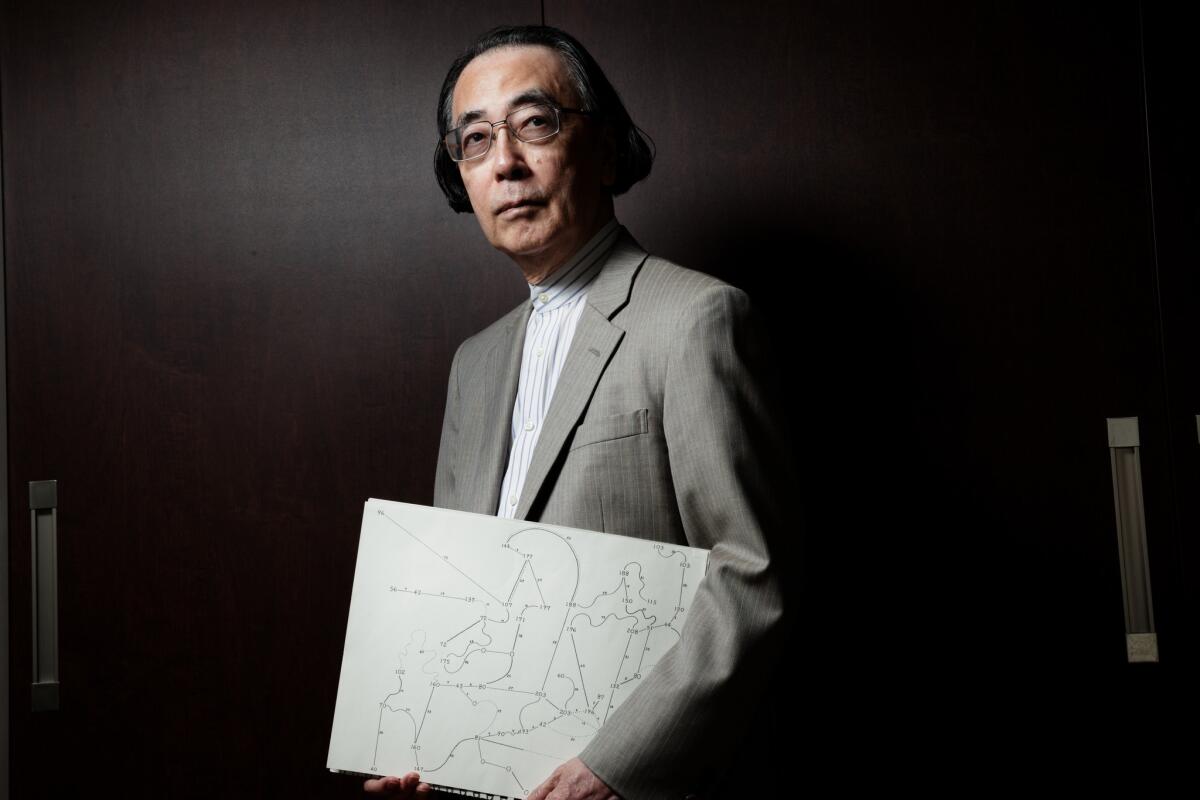

Reporting from TOKYO — When composer Toshi Ichiyanagi arrived at my hotel near Suntory Hall for tea, he apologized for bringing a bag of his recent CDs, since it would add weight to my luggage. He laughed when he said that in halting English. He then smiled contentedly, knowing full well how hard it is to hear his current music outside of Japan.

Though his work receives little attention these days in the U.S. or Europe, the name of the 82-year-old composer — whose Piano Piece No. 4 was described by this newspaper in 1968 as “a sequence of nearly identical squeaks much like the cries of a hen turkey” — does pop up in surprising places.

Ichiyanagi became Yoko Ono’s first husband when both were emerging avant-garde artists in New York in the late 1950s, and that has made him a footnote in the art world and in pop culture. Happily, “Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, 1960–1971,” opening Sunday in New York at the Museum of Modern Art, does not diminish his importance on her early work.

The truth of the matter is that Ichiyanagi has long been one of Japan’s leading composers.

He played an invaluable role in the development of the entire postwar Japanese avant-garde scene. He was one of John Cage’s favorite students; he not only brought Cage and his ideas to Japan but also proved a decided influence on Cage and his American circle.

And now this reserved and youthful-looking dean of Japanese music has become one of today’s most imaginative and compelling composers of traditional works.

His Ninth Symphony, a wrenchingly meditative commemoration of the third anniversary of the Fukushima nuclear plant disaster and the 70th of Hiroshima, had its premiere earlier this year in Tokyo. Over the last quarter-century, he has written exceptional concertos for Western instruments and for traditional Japanese instruments, along with a considerable repertory of solo piano and chamber pieces, film scores, experimental electronic music and music theater works.

On a conceptual level, his music examines philosophical, ecological, spiritual, political, scientific and broadly cultural themes. On a sonic level, it produces a visceral feel for the awe and violence of nature, the smell and timelessness of the sea, along with the mysteries of sex and food. Even with quietude becoming more commonplace than turkey cries in his late work, Ichiyanagi’s pieces still retain their explosive power.

I began our interview with questions about “From the Works of Tadanori Yokoo,” which is from the late ‘60s and is the most peculiar opera I’ve ever encountered.

It begins with a pop-like Japanese folk song. Next, one man teaches another a pop tune at the piano, repeating a simple melody over and over, one-finger style. An electronic drone is transformed into a siren that ushers in a fascist march tune. There are moans of a woman making love in the background of a collage that includes the Japanese rock group Flower Travellin’ Band. Croaking frogs introduce a snippet of “Swan Lake.” There is some Bach, and there are church bells.

Musically this makes for ineffably compelling listening, startling and engaging at every turn. But all Ichiyanagi will say is that he wrote five conventional operas between 1995 and 2005, and that he is not very interested in opera anymore. When I ask him about returning to his classical roots in his symphonic work, he notes he still writes experimental music.

“Most of the boundaries are lost,” Ichiyanagi concludes. “I don’t know whether that is a good thing.”

“Lively” is his favorite English adjective, and it was a search for liveliness that brought Ichiyanagi to New York in 1954. He was born in Kobe in 1933, moved to Tokyo with his parents when he was 3 and studied music privately. He grew up under harsh wartime conditions and describes Tokyo as a grim postwar city.

“I was not a good student and was interested in other things besides music,” although he had become an accomplished pianist and begun to win composition prizes already in his teens. Yet even in the early 1950s, he was musically ahead of his time. It was Ichiyanagi who somehow got his hands on a score by French composer Olivier Messiaen and showed it to his friend Toru Takemitsu, hospitalized with tuberculosis, in 1952. That was what led Takemitsu, who became Japan’s best-known composer, into forging a new instrumental style of contemporary Japanese music that melded East with West.

Finding Tokyo suffocating, Ichiyanagi went to New York not knowing what to expect other than that it would be lively. He enrolled in the Juilliard School with the ambition of becoming a 12-tone composer. “But there was no teacher interested in 12-tone music, so I concentrated more on piano.”

There is a little more to it than that. Even without pursuing modernist techniques, he became a star composition student, won awards and studied at Tanglewood with Aaron Copland. He also developed into a virtuoso concert pianist.

In 1956, he met Ono, another young Japanese artist living in New York. They were almost the same age, born two weeks apart. She too had classical music training and once harbored hopes of writing 12-tone music.

Ichiyanagi did not, like Ono, have wealthy parents and thus was not acceptable to Ono’s family, so the couple eloped. They lived like young avant-garde artists, but both retained their affection for classical Japanese culture as well.

Ono, whom Ichiyanagi describes as having been a poet at the time he met her, encountered Cage in classes on Zen Buddhism given by D.T. Suzuki at Columbia University. Ichiyanagi heard a Cage piece at a recital by pianist David Tudor and became enthusiastic about avant-garde American music.

The young composer enrolled in Cage’s classes at the New School, and his wife always came with him to audit. It was in these classes that both found their direction as artists, although ironically that was a direction that would quickly move them apart.

From Cage, Ichiyanagi discovered how to open his music up to new influences while remaining true to his Japanese heritage. Graphic notation was of the most interest, because he could write music in ways consistent with his calligraphic skills. Cage’s classes, which attracted poets and artists more than composers, became the foundation for the Fluxus movement, which viewed art as the result of actions. This showed Ono what to do.

Ichiyanagi and Ono were soon living apart — he was never quite as avant-garde as she — although they remained close. Having learned that Tokyo had become a more modern city, he returned in 1961 and quickly became a leading experimental figure in the arts. He prepared the way for Ono’s return as well. The next year, he and Ono hosted Cage’s first tour of Japan, which turned the country on its ear. Ono sang Cage’s “Aria,” and she also performed Cage’s “Water Walk” while lying on piano strings as the composer played.

On the trip, Cage premiered “0’00” “ — the follow-up, a decade later, to his famous silent piece, “4’33”.” Dedicating it to Ichiyanagi and Ono, Cage simply asked for the performer to undertake a dedicated action, with the sound of the proceedings amplified.

One aspect of “Cage Shock,” according to Ichiyanagi, was that the American composer “acted like a Buddhist monk. That was very striking for us. In Japan, Buddhist monks and ordinary people are very separated. But Americans can bring the same ideas to their lives and their professions.”

For composers, “that showed us that we could approach traditional music from a contemporary point of view and the other way around too.”

Ichiyanagi discovered something even more remarkable from “Cage Shock.” Japanese classical musicians remained inflexible, but those who played the traditional music proved receptive to performing from graphic scores, since this resembled the ancient approach. That, he says, is what made the final “connection between the traditional way of thinking about Japanese music and modern art, because most of Japanese traditional art is total art involving dancing and painting along with music.”

For Cage, there was “Ichiyanagi Shock.” Long motivated by Asian thought, which Cage first discovered as a boy growing up in Los Angeles, he found on this Japan trip a justification for what he had been doing and would continue to do for the rest of his life. One of the projects he was thinking about at the time of his death in 1992 was a “Noh Opera,” the idea having its roots in being taken to Noh theater on this trip 30 years earlier.

But “Cage Shock” was too much for Ono. She became overwhelmed and had a nervous breakdown. In a 1963 letter to Cage, describing his divorce, Ichiyanagi laments that he was resigned to not have been able to make Ono happy.

Whether he has been able to make Japan happy is another matter. Throughout the ‘60s he adapted Cage’s ideas to his own voluminous interests and reached a kind of climax with his kitchen-sink “Tadanori Yokoo” opera.

It was also around this time that Ichiyanagi became more prominent in the U.S. Choreographer Merce Cunningham used Ichiyanagi’s ensemble piece “Sapporo” as the music for the dance “Story,” which had its premiere with Cage conducting at UCLA.

Ichiyanagi spent 1967 in New York, where he discovered the new Minimalism and added that to his collection of compositional techniques. He came to Los Angeles for concerts a couple of times in the 1970s.

But Japan was where his career remained centered. His move into more traditional classical media, he says, was motivated in part by his need to make a living. As he became better known, performers, ensembles and even opera companies asked him to write scores, so he did. His facility with many different musical and cultural styles, his extraordinary ear for striking instrumental sounds, his philosophical bent all meant that one kind of music in a piece may lead to its opposite in ways that are hard to explain but make sense aurally.

What is hard to explain is the lack of interest outside of Japan in what is now a rich and extensive body of work. Most of his records are on Japanese labels not distributed in the U.S. He has written three books in Japanese about music that have not been translated. Ichiyanagi was represented by only a small organ piece at a weeklong festival of Japanese music put on by his alma mater, Juilliard, earlier this year.

But he has landed on the radar in Finland. “It just suddenly has happened,” Ichiyanagi says mysteriously, “and I’ve gone there three times in the last five years.”

One of the CDs he gave me includes his otherworldly Piano Concerto No. 5 “Finland” for Left Hand, written three years ago. One of his newest pieces is a clarinet sextet written for Finnish musicians, notably clarinetist Kari Kriikku.

Ichiyanagi says that he has been hearing much about Los Angeles. “Is it now lively?” he asks.

When I say it is, he replies: “It is only nine hours to fly,” as if reading my mind. What are we waiting for?

Twitter: @markswed

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.