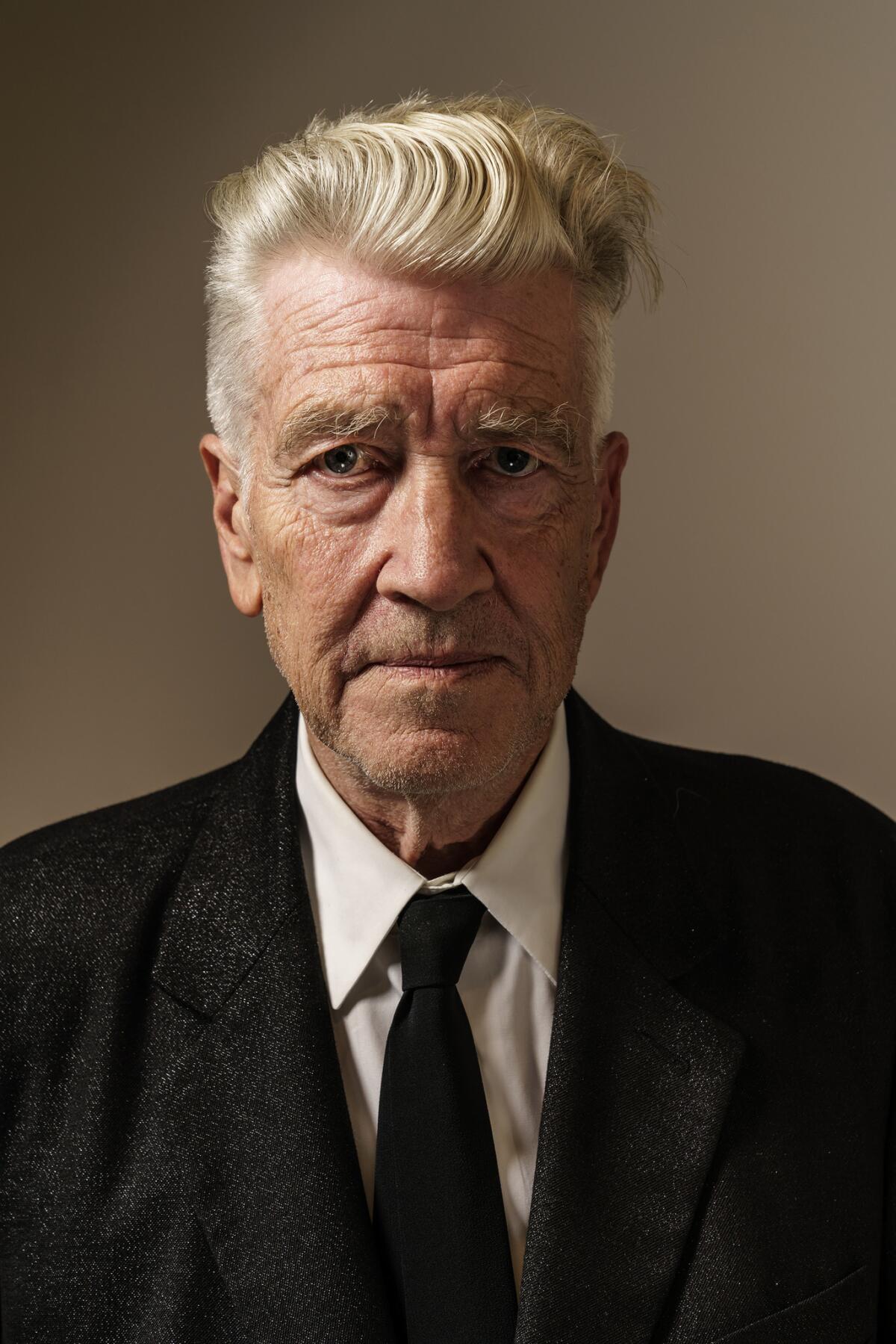

In Conversation: David Lynch, the director as painter, festival impresario and ant collaborator

- Share via

On the windowsill of his painting studio in the Hollywood Hills, David Lynch has enlisted a colony of ants to help create some art. He’s molded a tiny human head out of mortician’s wax and filled it with cheese, chicken and sugar. Two nights earlier, Lynch filmed the ants in a feral march of disintegration.

“They’re hollowing that head out. It’s incredible,” the acclaimed director said with a smile. “They work 24/7. The dish behind it is filled with Coca-Cola, and they’re nuts about Coca-Cola, and they’re nuts about what’s inside that head.”

Lynch may have picked up a camera to capture the ants in another of his explorations into the surreal and grotesque, but these days, he’s just as likely to grab a paint brush. Since completing last year’s long-deferred third season of his television series “Twin Peaks,” Lynch has largely devoted himself to his original medium: painting.

Many of his newest paintings, collected in the exhibition “I Was a Teenage Insect,” are now at Kayne Griffin Corcoran through Nov. 3. (A series of his lithographs, “David Lynch: Dreams — A Tribute to Fellini,” are at the Fellini Foundation at the Maison du Diable in Sion, Switzerland, through Dec. 16.) The “Teenage Insect” pieces are large mixed-media works of what he calls “childlike distortion,” filled with mystery, terror and bliss, and occasional words scrawled across the canvas.

Francis Bacon says there is zero story in his work. He hates stories. Me, I love stories. The words help the story, and I like the shape of words.

— David Lynch

In the late-1960s, before he moved to Los Angeles and made “Eraserhead,” his first full feature, Lynch studied painting at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia. All these years later, he’s at it still in his mostly open-air studio, leaving a trail of spent cigarettes and splashes of coffee on the concrete floor.

In addition to his painting, Lynch released a memoir of sorts this summer, “Room to Dream,” written with Kristine McKenna, and a book of photography called “Nudes.” He’s also preparing for his annual Festival of Disruption — with music, film and art — at the Theatre at Ace Hotel on Oct. 13 and 14.

The event, which this year includes guests Francis Ford Coppola, Grace Jones and Carrie Brownstein, raises funds for the David Lynch Foundation, established to promote the benefits of Transcendental Meditation. Sharing the technique that has been essential to his life and work is now a central mission for the artist: “Every human being has got a treasury inside.”

The audience for an exhibition can be much smaller than for a film. Do you feel the same about both?

It’s the same showing a film or a lithograph or a painting. You build a thing to be seen and experienced mainly for yourself. What’s thrilling in cinema is to go into a great theater with a giant screen, beautiful sound and experiencing what you built. You can see it and feel so good about it. You hope that others will feel good about it too. That’s not always the case.

There is an expression: “Man has control over action alone, never the fruit of the action.” And that is really true in art, painting and cinema. You do the best you can, and then you release it. It depends on the way the world is, who is in the audience. Everybody is different on the surface.

When you were an art student in the ’60s, it was the time of pop art. Did you feel connected to what was going on?

No. Pop art, I’m not wild about. The same way with film — I’m not in the film world so much. So you just concentrate on the ideas you’ve fallen in love with.

Does Francis Bacon tower above the rest in terms of who initially influenced you?

Yeah. In 1966, I went to New York and saw a Francis Bacon show at the Marlborough Gallery, and it was a huge influence and inspiration. Ed Kienholz and Francis Bacon are two of my favorites.

There are a lot of words incorporated into your new paintings. Do the words come first, or are they in reaction to the image?

Sometimes they come first, and sometimes they come last. They’re essential to me. Francis Bacon says there is zero story in his work. He hates stories. Me, I love stories. The words help the story, and I like the shape of words.

Are the stories based on experiences?

No, they’re based on ideas that come. I always equate it to fishing. You’re out fishing and you don’t know what you’re going to catch. And you don’t know how long it’s going to take to catch it. And you don’t know that you’re going to love the fish that you catch. You’re just fishing for ideas. Some ideas seem to come from another place. It’s daydreaming and thinking, and once in a while, you’ll catch an idea that you love. But you’ve got to have patience to go out and lower the hook.

You’ve always painted, but when your film career took off, you didn’t really pursue exhibitions.

I had a couple of shows when I was a student at the academy. Then there were no shows for a long, long time. And I didn’t really have any money for a setup for painting until after “Blue Velvet.” I had one show during “Dune” at this gallery in Puerto Vallarta, where [director] John Huston came to see the show. He bought a watercolor from me. It was pretty great.

You’ve always been interested in things that are decayed or wounded in some way

The textures in those things are really incredible — when things pop open and fester in a dance of organic phenomenon, the textures and the mood, the way they are shaped. It’s just unbelievable what’s going on in nature.

Do your ideas surprise you?

If I get into a thing, and a new idea pops up, it’s a thrill beyond the beyond. It happens through action and reaction. Sometimes you get to a place where the thing isn’t working and you can’t see your way out, so you bite the bullet and destroy. And in destruction, sometimes comes something completely thrilling. You can’t be afraid to destroy.

As with your films, you don’t like explaining your paintings.

It doesn’t do any good. A lot of painters, they talk like crazy. I just don’t get it. It’s there on the wall. There’s a thing that happens: a person stands in front of a painting, and they are going to react based on what’s inside the person. Everybody’s experience is a little different or a lot different. Some people hate the thing. Some people love the thing. Some people are lukewarm. The work stays the same.

You’ve often spent time as a still photographer. A few years ago, you put out a book of photos you took of factories. And you recently released a book of nude still photography.

I’m not alone; I love the female form, and I like finding these shapes and the way light plays on it. It’s so great for photography — black-and-white and color. But black-and-white can be so beautiful with abstractions. I photograph factories in 35 mm. I really want to photograph some old places in downtown L.A. before it changes too much.

With “Inland Empire” in 2006, you were among the first to shoot a feature film with a digital camera. As the technology has evolved, are you comfortable with the near-perfection of modern digital?

It depends on the idea. A lot of times, if you see too much, there’s no mystery. It’s how you light a thing. Early 35 mm wasn’t so sharp. It just had a feel that really served some things so well. The beautiful thing about digital is you can manipulate it like crazy when you’re finished. You go in with hi-res and perfect focus, perfect exposure, but then you can tear it apart, you can degrade it, you can do anything. It’s so beautiful.

You started your Festival of Disruption in Los Angeles, and it’s grown into an annual event.

We’ve got a great team running it. They run everything by me, but they’re really taking care of it. It gives you a really great feeling when the festival is done. It’s always about disrupting the bad and bringing in the new good. A lot of people don’t believe for a second that peace is possible, but it is and is going to be.

What drives you to try all these different creative mediums?

I find that every medium talks to us, if you just start doing it. Watercolor paper is a certain way, and watercolor paint is a certain way. You say, “Oh, this is different from oil painting on a canvas.” Different things happen. You start to get a dialogue and a feel for what it does. It’s the same with every single medium. They’re infinitely deep. You can’t exhaust it.

Any mediums left to try?

Sewing. I got an industrial sewing machine. I would like to be able to sew things and make stuff. I would like to know how to weld as well. I like to watch these car shows where they customize cars. Working with metal is just so beautiful. But TIG welding, you need these tanks of gas, and it sort of scares me; I would want to put them in cement bunkers in case they blow up. But welding is an art.

David Lynch: “I Was a Teenage Insect”

Where: Kayne Griffin Corcoran, 1201 S. La Brea Ave., Los Angeles

When: Tues.-Sat., 10 a.m.-6 p.m., through Nov. 3

Info: (310) 586-6886, kaynegriffincorcoran.com

David Lynch’s Festival of Disruption

Where: The Theatre at Ace Hotel,

When: Oct. 13-14; day sessions begin at 10:30 a.m., night programs at 8 p.m.

Tickets: $55 (for single day-session pass) - $999 (for donor-level two-day pass)

Info: festivalofdisruption.com or acehotel.com

See all of our latest arts news and reviews at latimes.com/arts.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.