Tales of a new Chinatown: The San Gabriel Valley stories from ‘Flower Drum Song’ author C.Y. Lee

Author C.Y. Lee in his home office in Little Ethiopia in Los Angeles.

- Share via

The writer C.Y. Lee, dapper at 99 with a leopard-skin printed handkerchief wrapped snugly around his neck, sits in his home office near Los Angeles’ Little Ethiopia happily holding court. Surrounding him are piles of typed manuscripts, letters and notes. The walls are crammed with yellowed newspaper clippings, certificates from local assemblymen and Chinese American literary societies, a key to the city of San Francisco — documenting a career bookended by telling two different stories of Chinese life in America.

While Lee’s name is no longer well known, he shaped some of the first impressions of the Chinese American experience after he skyrocketed to fame in 1957 with “The Flower Drum Song,” a comedic drama about a Chinese father fighting to preserve traditions in San Francisco’s Chinatown and the conflict with his Americanized, boundary-pushing sons. Now he is endeavoring to introduce Americans to a lesser-known “new Chinatown” — the San Gabriel Valley.

See more of Entertainment’s top stories on Facebook >>

Lee remains an exuberant storyteller. Many of his tales are of his glory moments after Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein, along with producer Joseph Fields, adapted his novel in 1958 into the first Broadway musical showcasing Chinese Americans. Parades greeted him in San Francisco’s Chinatown when “Flower Drum Song” went on tour there. He dined with the Marx brothers. In 1961, “Flower Drum Song” became the first major Hollywood studio film about and starring Asian Americans.

His adult daughter, Angela, who shares the house with her brother and her father, indulges Lee, adding details to his stories when his memory falters. She searches through the room for the manuscript he is working on, an English translation of a book of stories written about the San Gabriel Valley.

The production may not be quick, but she says he remains determined, spending most of his time writing or editing — when he is not dozing.

Lee explains the book, whose title translates from the Chinese as “Manchu Gown Lady,” is the new Chinese American dream — in fact, his English-language title for it is “American Dream.” And it marks a radical shift from the story of the “old Chinatown” Lee told more than a half century ago.

They drove right past L.A.’s Chinatown. Lee was confused. “He took me to a city I’d never known...” Lee says. “Suddenly Chinese sign boards, neon lights...Asian faces everywhere.”

A native of Hunan who grew up in Beijing, Lee tells an extraordinary World War II-era immigration journey that included flying over the Himalayas chased by Japanese warplanes and zigzagging across the Pacific Ocean on a cargo ship to avoid torpedoes. For a time during the war, he was secretary to a Burmese statesman.

He eventually landed at Yale’s Drama School, where he believes he was the only Asian student. A visiting literary agent told him America, which had only recently repealed the Chinese Exclusion Act, was not ready for a Chinese playwright. She told him to try writing books instead.

A framed newspaper clipping of three pretty girls kissing a much younger version of himself hangs in C.Y. Lee’s home office in Little Ethiopia.

“I was heartbroken,” Lee says. Yet he also thinks the agent was correct. Chinese Americans were unknown to most of the country. But there was an appetite for stories about the Orient, proved by the success of James Michener’s “Tales of the South Pacific.”

Lee wanted a success, and to have one he needed to appeal to white Americans. While paying his bills as a columnist in San Francisco’s Chinatown and living on bowls of pork noodle soup, he developed “The Flower Drum Song.”

Activists would later criticize Lee for showcasing the exotic to lure white readers. But that is exactly what he was trying to do. His characters, who included herbalists and nightclub dancers, ate foods that were unknown to most Americans such as “medicine pigtail soup,” “smoked duck feet steamed with pork” or “bitter melon.”

“I wrote that novel totally for an American audience,” Lee says. “They don’t want to read about things they know already.”

It worked. Lee became the first Chinese American novelist to get a major publisher, the New Yorker printed an excerpt and a New York Times review applauded Lee for writing with “no omission of slang and sex and every regard for the popular taste.” The reviewer went on to note that the story provided rare access: “San Francisco’s Chinatown nowadays is no milieu for the novelist who is an outsider. With the slave girls vanished, also the racketeering tongs, the social life of the quarter is other than what it was, or had seemed to be.”

Lee is convinced that it’s not simply the exoticism that made “The Flower Drum Song” a bestseller but its accessibility. Readers of all backgrounds could identify with a vision of a Chinese American man with universal sexual appetites, insecurities and strife with his father.

After the success of “The Flower Drum Song,” Lee lived an assimilationist version of the American dream. He met his wife — a white writer from Petaluma — at a literary group that included Ray Bradbury. They moved to Woodland Hills and had two children.

Lee’s children didn’t learn Chinese, eat Chinese food or even interact with many Asians. “In our house when we grew up there was no real affiliation to China and Chinese,” says his son, Jay Lee. “We were Americans.” His daughter, Angela, further explains, “We grew up in the ‘60s and ‘70s,” she says. “It was Christie Brinkley. During that period of time it was all about assimilation.”

Lee wrote 10 more books in English. But while many were well received, none would approach the success of his first. His focus also shifted.

He wrote about the East and historical fiction rather than translating a contemporary Chinese American experience, which was increasingly far from his life.

“Flower Drum Song” receded from the public. Regional theaters did not produce the play because of a lack of Asian actors and the story’s increasingly controversial reputation.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Asian American identity politics churned on campuses. Many student leaders and intellectuals rejected Lee’s work as stereotypical, too upbeat and with a goal of losing ethnic culture to blend into the mainstream. The editors of “Aiiieeeee! An Anthology of Asian American Writers” derided “The Flower Drum Song” as “white supremacist” for contributing to a “saccharine patronage of Chinatown culture.”

Peter Kwong and Dusanka Miscevic, in their book “Chinese America,” write of the long-lasting effect of “The Flower Drum Song” as well as its shortcomings. “Lee’s slapstick comedy of generational conflicts exposed American racism and blamed it for making assimilation for both immigrant and American-born Chinese difficult. But it was at the same time infused with an optimism that embraced an America where differences of race, sex, class and nationality could be erased by the embrace of individualism and modernity.”

One afternoon in the early 1990s, Lee’s only Asian friend in Woodland Hills asked if he wanted to take a ride to buy a Chinese newspaper. When they drove right past Los Angeles’ Chinatown, Lee was confused. His friend responded: “Just wait and see.”

They were on their way to a different kind of Chinatown, one going through a radical transformation. “He took me to a city. I’d never known such a city,” Lee says, eyes glowing at the memory. “Suddenly Chinese sign boards, neon lights. And the people: Asian faces everywhere. All the cars going by had Asian faces.” It was the San Gabriel Valley.

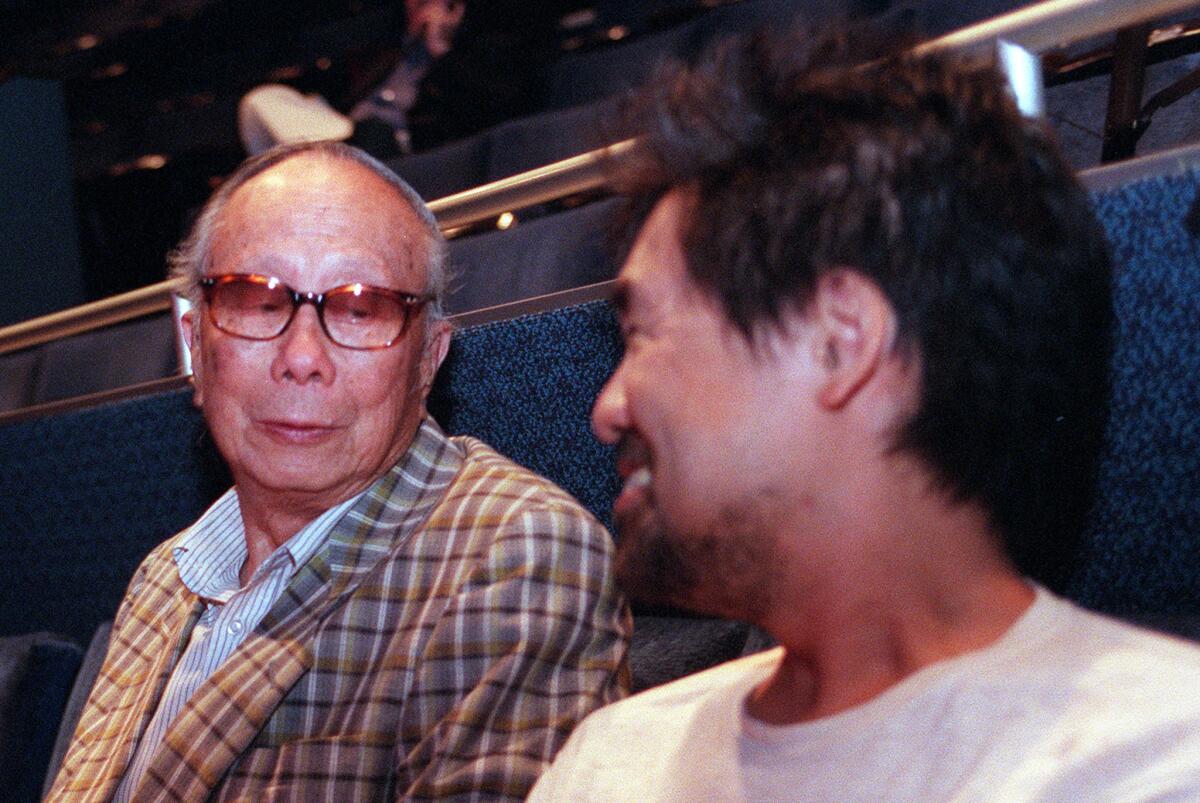

C.Y. Lee, left, with David Henry Hwang at a dress rehearsal for the 2001 production of ‘Flower Drum Song’ at the Mark Taper Forum. Hwang revived the musical based on Lee’s novel for a new generation.

That night, after buying a newspaper, his friend took him to a smoky nightclub where the women, educated and from Taiwan, swarmed. Soon he learned the attention was not for free: He was charged $20 a conversation.

This was not the mostly Cantonese-speaking bachelor’s society of San Francisco Chinatown that Lee knew so well. While some called the area Little Taipei, it was actually much more diverse. In the San Gabriel Valley, a new suburban Chinese America, with rich and poor from mainland China, Southeast Asia, Hong Kong and Taiwan, was emerging. There were immigrants who had been in the country for 20 years and never learned English, wealthy entrepreneurs and young people who were born in the Asian suburbs and spoke English perfectly, but had no intention of ever leaving for the “American suburbs.”

Lee was captivated. Soon he packed his bags and found an apartment in the heart of the new Chinese America. There was a new story he wanted to tell — and to live.

Activists...criticize Lee for showcasing the exotic to lure white readers. But that is exactly what he was trying to do. “I wrote that novel totally for an American audience.”

America’s Chinese immigrant population has grown to more than 2 million. Most Chinese are suburbanites today, according to Kwong, a professor of Urban Affairs and Planning at Hunter College.

Many live an existence like Lee’s in Woodland Hills or what the television show “Fresh off the Boat” depicts of men and women standing out as the few lone Asians in a predominantly white community. Yet increasingly suburbs with significant Chinese populations have popped up around the country, near San Jose, in New Jersey around Princeton. The biggest is the San Gabriel Valley.

After Lee’s wife died in 1997, he took up permanent residence in Alhambra with the intention of writing a new saga of Chinese American life.

This time, though, he wrote the story for a Chinese audience rather than an American one. He was interested in returning to his roots, no longer barred from China as he was during the hard-line days of the Cultural Revolution, and found more interest in this emerging community from China. Lee wrote in Chinese for a Taiwanese newspaper and publisher.

He found a rich life in the San Gabriel Valley to document: “They have nightclubs, dancing halls, everywhere is restaurants,” he says of the new immigrants. “Grocery stores, and a lot of people have romance, fights. All kinds of stories.”

One day America’s best-known contemporary Chinese American playwright, David Henry Hwang, invited Lee for lunch in Monterey Park.

Hwang, who rose to fame with his Obie Award-winning “F.O.B.” and Tony Award-winning “M. Butterfly,” grew up in the San Gabriel Valley in the 1960s.

But his experience was very different than the one Lee discovered: “It was sort of a sleepy L.A. suburb,” he says by phone. “Pretty middle class, working class. Ethnically more white and Latino, with a smattering of Asians.”

As a college student at Stanford University in the 1970s, Hwang was swept up in identity politics. “As part of this movement, we condemned (rather simplistically) virtually all portrayals of Asian Americans that had been created by non-Asians,” he wrote in an introduction to a re-release of “The Flower Drum Song” in 2002. “So I ended up protesting ‘Flower Drum Song,’ which had become associated almost exclusively with the movie and musical, as ‘inauthentic.’”

But as a middle-aged man he reread it and discovered a forgotten piece of Chinese literature — one he thought could be better transformed for the stage from the perspective of an insider.

Hwang revived the work, bringing it to the stage in 2001 in Los Angeles and, after an extended run, on to Broadway. For a brief moment, the English-speaking world remembered or was introduced to C.Y. Lee. But the play did not do particularly well in New York, and Lee went back to looking for new stories and telling whoever would listen some of his fabulous old ones.

In 2008 Lee came down with pneumonia and after a stay in the hospital he moved in with his children. He lives downstairs and they live upstairs, and sometimes they collaborate on film projects.

Lee continues to develop his book on the San Gabriel Valley, with chapters such as “The Oriental Cassanova,” “Two Chinese Pig Farmers Visiting Hollywood” and “An Unusual Job for a Temporary Worker.” His health, though, sometimes gets in the way. His memory is slipping as is his hearing.

Like Old Master Wang, the patriarch in “Flower Drum Song,” he has seen his Chinese community change during his lifetime.

“Perhaps in fifty years most of the familiar sights and smells in Chinatown would be gone,” Old Master Wang says at the end of “Flower Drum Song.” “Perhaps there would be no more clatter of mah-jongg behind closed doors, no more operatic music of drums and gongs, no more noodle factories, no old-fashioned barbershops with all the traditional services, no more retired old men reading Chinese newspapers, no more grocers with abacuses, no more thousand-year-old eggs, taro roots or dried seaweed….”

Old Master Wang predicts his sons will not take these traditions with them, but completely assimilate into a 1950s vision of white America and baseball.

Lee lived through a personal transition like this one. But he also lived to experience a new vision of Chinese life in America; a life that neither Old Master Wang, or Lee, ever predicted.

Twitter: @dhgerson

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.