5 pieces in the Broad collection that highlight Pop art history and its almost immediate impact

- Share via

T

he Broad collection is especially strong in classic 1960s Pop art and its subsequent offshoots. Here are three Pop masterpieces by Ed Ruscha, Robert Rauschenberg and Roy Lichtenstein, plus two by John Baldessari and Richard Artschwager that show Pop's almost immediate impact on other artistic directions.

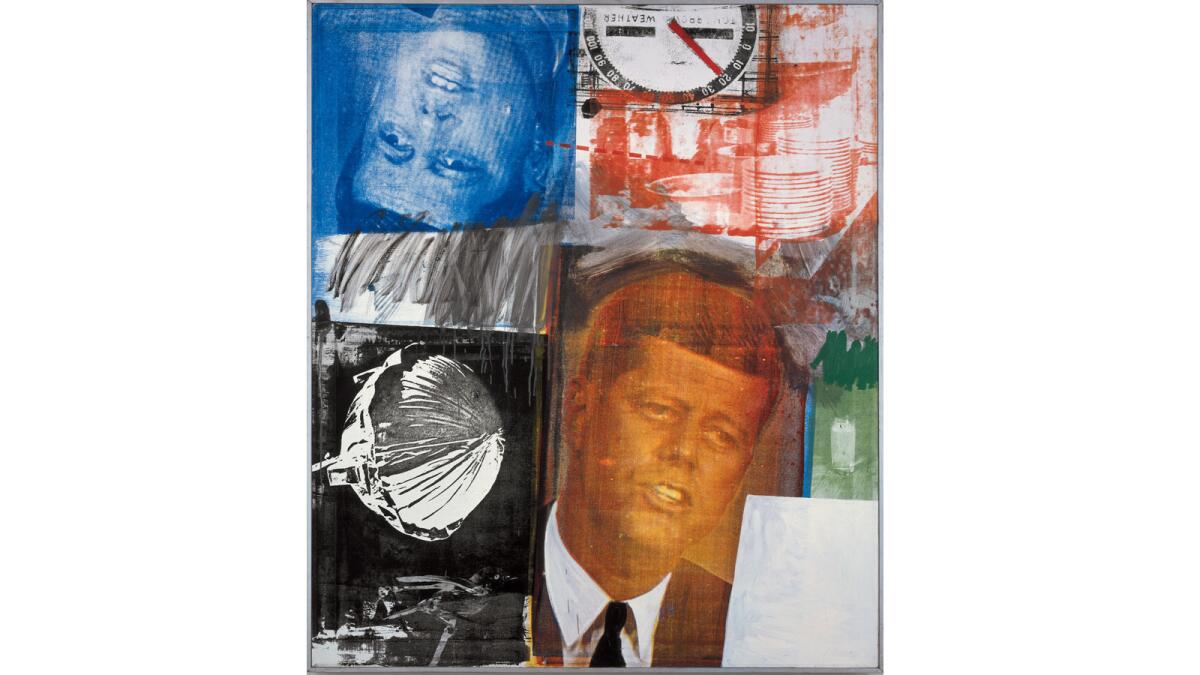

Robert Rauschenberg, "Untitled," 1963, oil and silk-screen inks on canvas

Robert Rauschenberg, “Untitled,” 1963, oil and silkscreen inks on canvas, 58 x 50 in. (147.32 x 127 cm)

Robert Rauschenberg, "Untitled," 1963, oil and silkscreen inks on canvas, 58 x 50 in. (147.32 x 127 cm) (© Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / VAGA, NY / The Broad)

The roster of photographic images that Rauschenberg silk-screened onto this canvas creates both a homage and a signal of distress at the edge of the New Frontier.

It includes John F. Kennedy at a press conference and shown twice, right-side up and upside down, one painted in full color, the other in the cool blue of a television screen; the bulbous combination of a rescue parachute and balloon, meant to be used in an emergency if an astronaut had to eject out of a Gemini space capsule; and an otherwise life-sustaining glass of water, here painted nauseous green. Made in the immediate, traumatic aftermath of Kennedy's assassination, the painting is one of a series for which Rauschenberg became the first American artist to win the Grand Prize at the Venice Biennale.

FULL COVERAGE: Fall arts guide 2015

Ed Ruscha, "Norm's, La Cienega, on Fire," 1964, oil on canvas

Ed Ruscha, “Norm’s, La Cienega, on Fire,” 1964, oil and pencil on canvas, 64 1/2 x 124 3/4 x 2 1/2 inches (163.8 x 316.9 x 6.4 cm)

Ed Ruscha, "Norm's, La Cienega, on Fire," 1964, oil and pencil on canvas, 64 1/2 x 124 3/4 x 2 1/2 inches (163.8 x 316.9 x 6.4 cm) (©Ed Ruscha / Gagosian Gallery / The Broad )

Landscapes are the oldest painting tradition in the West, but they're not exactly like this one. And 1964 saw the worst local fire season since the legendary Bel-Air blaze, but neither did it sweep into the L.A. basin, sticking instead to the hills.

Ruscha's picture set ablaze a rendition of a Googie-style coffee shop just down the street from the city's then-bustling strip of La Cienega art galleries. He applied traditional oil paint and canvas to a sharp — and specifically commercial — graphic-design style. The result is a painting that melds artistically conservative landscape with renegade billboard motifs. When he burned down Norm's popular restaurant, Ruscha burned down art's norms too.

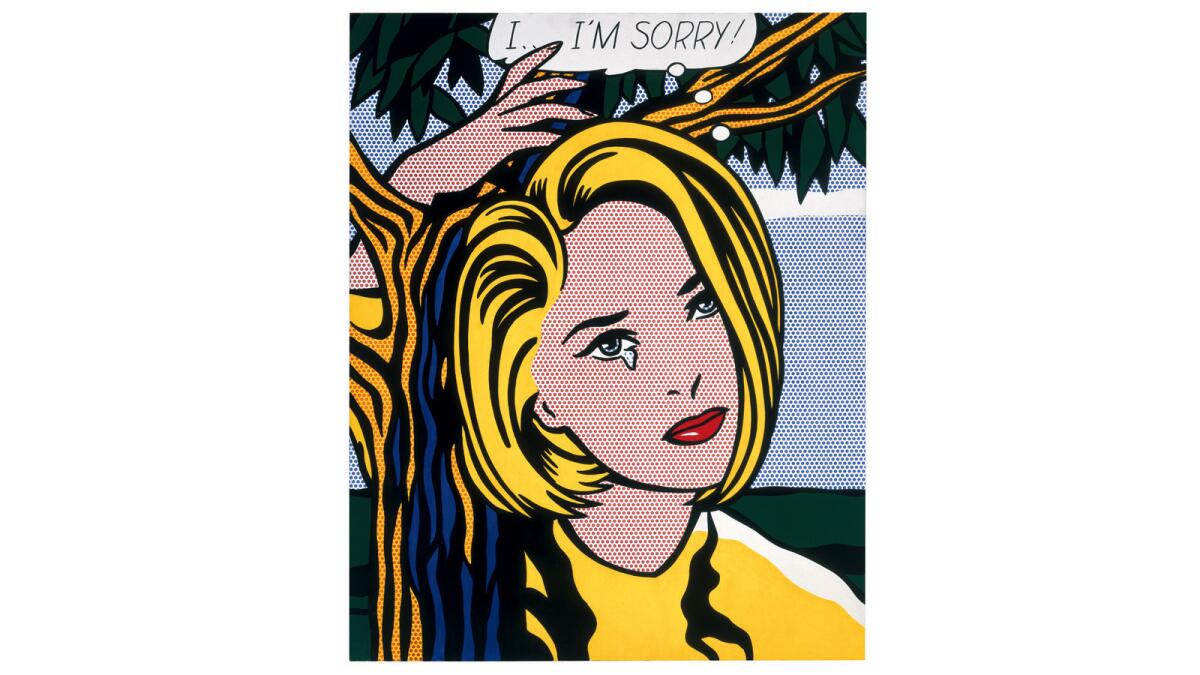

Roy Lichtenstein, "I … I'm Sorry," 1965-66, oil and magna on canvas

Roy Lichtenstein, “I...I’m Sorry!,” 1965-66, oil and magna on canvas, 60 x 48 in. (152.4 x 121.92 cm)

Roy Lichtenstein, "I...I'm Sorry!," 1965-66, oil and magna on canvas, 60 x 48 in. (152.4 x 121.92 cm) (©Estate of Roy Lichtenstein / The Broad)

The most common subject for Pop art in the 1960s was other art, buried within a commercial veneer of advertising, magazines, tabloid newspapers and — famously in Lichtenstein's case — comic strips. The artist knits together two classic genres, one Modern and one Renaissance, in this marvelous example.

A moist tear wells in the young blond woman's eye, bringing Picasso's dramatic series of "weeping women" paintings to mind. As she lifts and wraps her arm around a tree branch, Renaissance pictures of Eve reaching up to pick the fateful apple from the tree of knowledge also reverberate in the artistic back story. Yet with no apple anywhere in sight, she's apparently weeping over a fall from grace that has already happened to humanity — and for which she haltingly apologizes. Painting just when the feminist movement was taking off, Lichtenstein made a wicked satire of the blame-the-victim mentality still prevalent today.

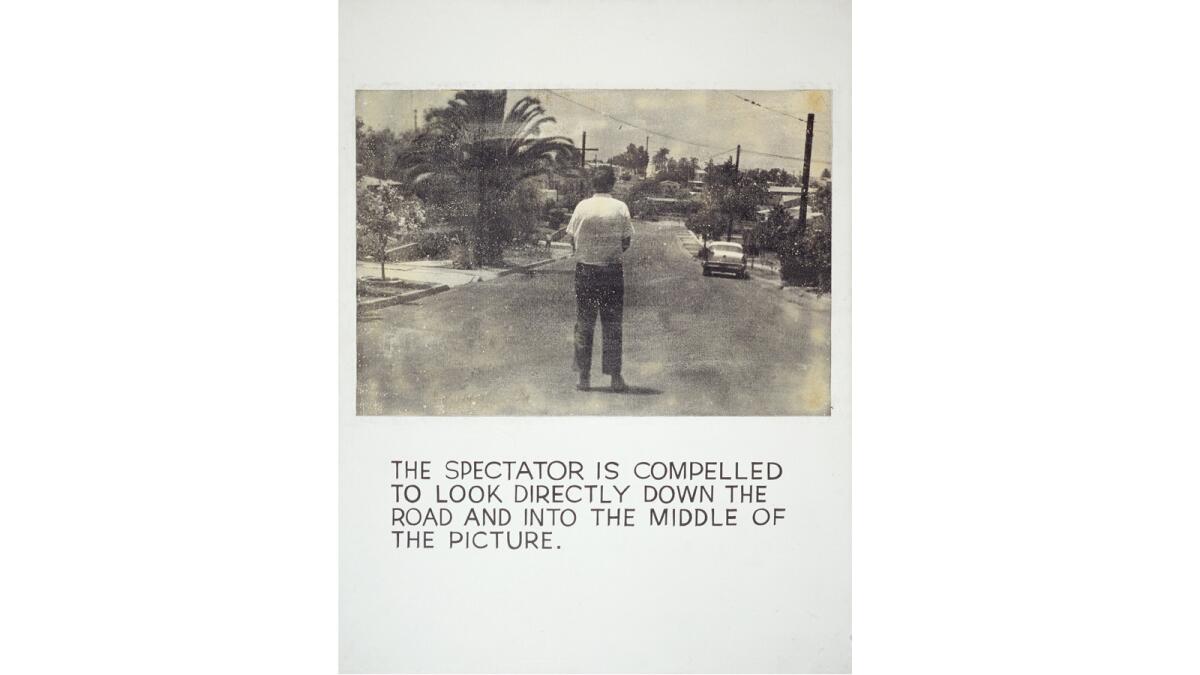

John Baldessari, "The Spectator Is Compelled … ," 1966-68, acrylic and photo-emulsion on canvas

John Baldessari, “The Spectator Is Compelled...,” 1966-68, photographic emulsion and acrylic on canvas, 59 x 45 in. (149.86 x 114.3 cm)

John Baldessari, "The Spectator Is Compelled...," 1966-68, photographic emulsion and acrylic on canvas, 59 x 45 in. (149.86 x 114.3 cm) (© John Baldessari / The Broad)

Baldessari quickly understood the implications of Andy Warhol's radical silk-screen paintings, in which an ordinary but embellished photograph performed a masquerade as a painting. He began to print unembellished black-and-white photographs —mostly self-portraits — directly on canvas.

The result was weird and witty works such as this one, which break the established rules of "good art." The composition instructs the viewer on how to correctly look into the painting's illusion of deep space, successfully succumbing to the painter's formal directives. Meanwhile, the ungainly artist plants himself smack in the middle of the scene — standing in the way and blocking the view down life's long and winding road.

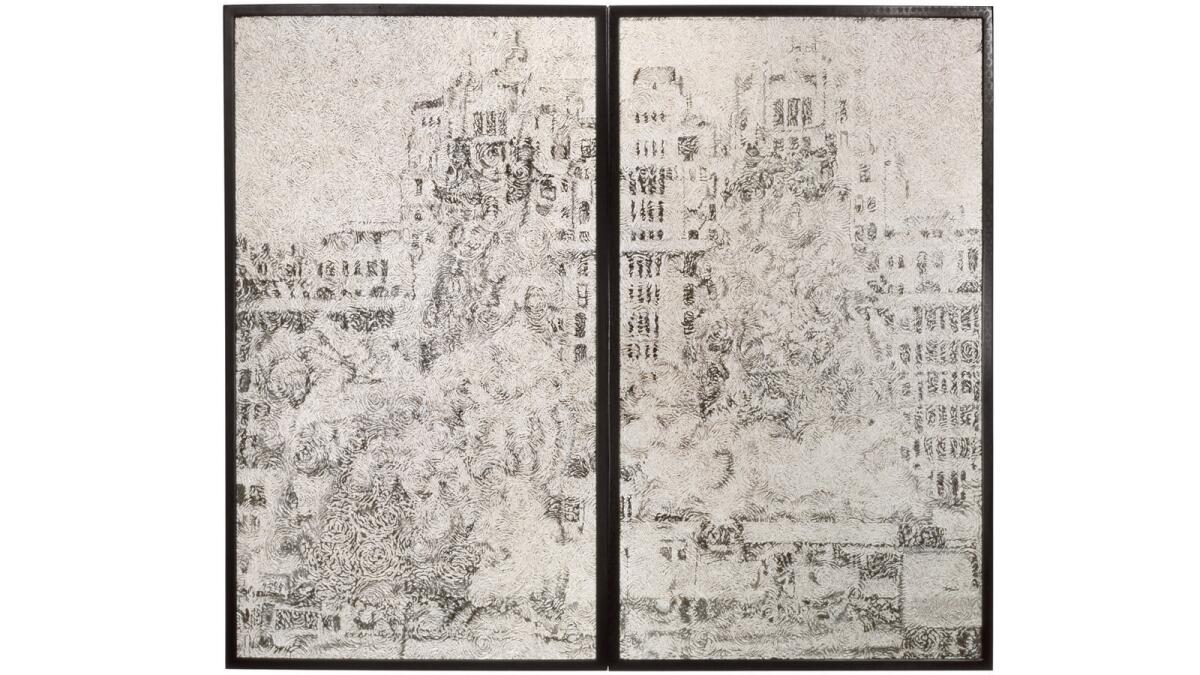

Richard Artschwager, "Destruction V," 1972, acrylic on Celotex board

Richard Artschwager, “Destruction V,” 1972, acrylic on Celotex, with metal frames, two panels, 41 1/4 x 49 3/4 x 1 in. (104.78 x 126.37 x 2.54 cm)

Richard Artschwager, "Destruction V," 1972, acrylic on Celotex, with metal frames, two panels, 41 1/4 x 49 3/4 x 1 in. (104.78 x 126.37 x 2.54 cm) (© 2015 Richard Artschwager/ ARS, NY / The Broad)

A carpenter and furniture-maker originally trained as a scientist, Richard Artschwager hit on the idea of using Celotex, a textured fiberboard with a raised surface of whorl-patterns, instead of canvas as a painting support. The narrow little raised Celotex ridges hold thin washes of black acrylic paint, making the image look fuzzy — almost like a slightly out-of-focus snapshot or a grainy picture on newsprint.

The two-panel "Destruction V" shows the demolition of the once-glamorous Traymore Hotel in Atlantic City, N.J., at two moments of midblast, as the edifice begins to topple. Copied from a series of newspaper photographs, Artschwager's painting is a representation of a representation. The building is disappearing, but your eyes strain to pull the fuzzy picture together to see what's actually happening. The tension between an established world in collapse and the individual struggle to hold it together speaks eloquently of the 1972 painting's fraught moment as well as acknowledging the encroachment of mass media onto direct lived experience.

Twitter: @KnightLAT

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.