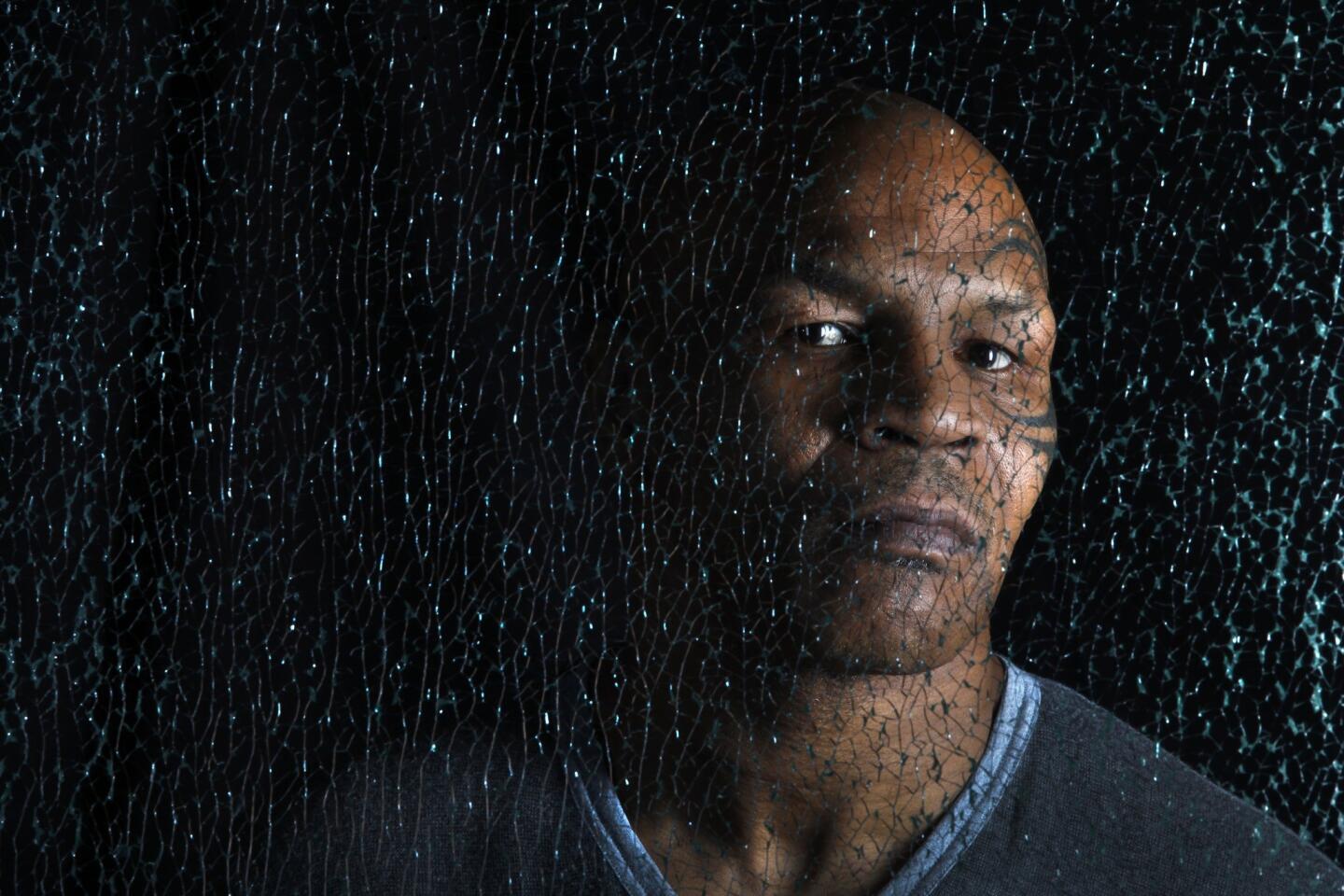

Review: ‘Mike Tyson: Undisputed Truth’ is a knockout

- Share via

If there was one ring in the world that I, a weakling theater critic, knew I could knock Mike Tyson out in, it was the Pantages Theatre, where “Mike Tyson: Undisputed Truth” played this past weekend.

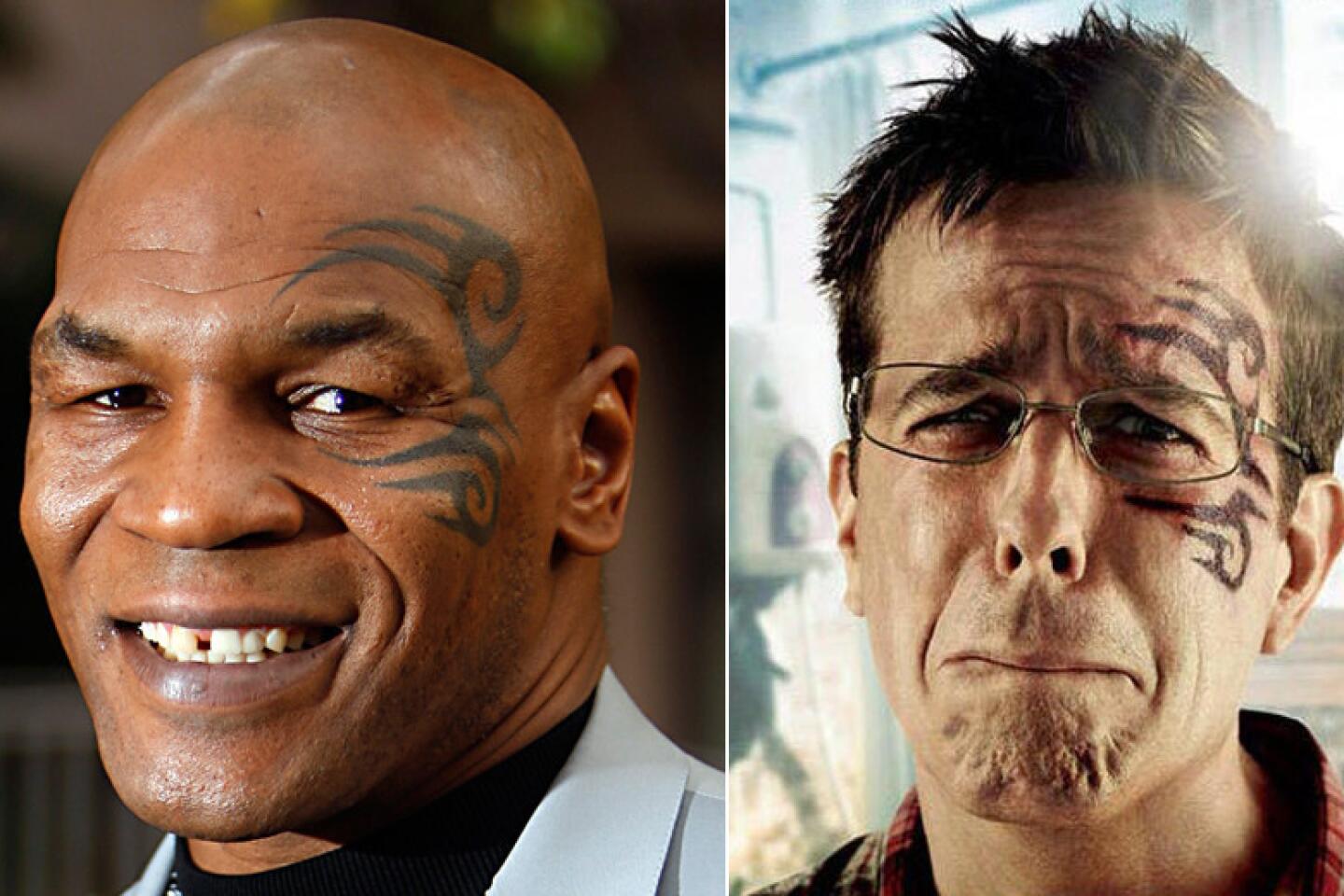

Tyson might have 100 pounds more muscle on him than I do, not to mention a facial tattoo out of my mother’s worst nightmare, but I was the one trash-talking all week about our upcoming bout.

“I want a piece of him,” I said loudly to no one in particular in the newsroom. “When I’m through with him, he’s going to wish he was touring as an uncredited extra in ‘Wicked.’”

PHOTOS: Mike Tyson in pop culture

But like all those mouthy contenders who ended up flat on their back in the first round, I underestimated the former heavyweight champion of the world. He came to box with himself, to thrash out his story before his fans, leaving no controversy unturned and me dazed with a sympathy I hadn’t expected.

Yes, he threw a few rabbit punches at sensitive moments and resorted to rope-a-dope in a couple of anecdotes that made him seem more victim than assailant. But there were steady jabs aimed squarely at his own foolishness. I thought I’d be cold-cocking him right now in print, but his mix of street swagger and newfound humility conquered me.

Tyson’s diction isn’t meant for the stage. (“Julius Caesar” isn’t in his future). But he has something that isn’t encountered all that often in the theater — an authentic voice.

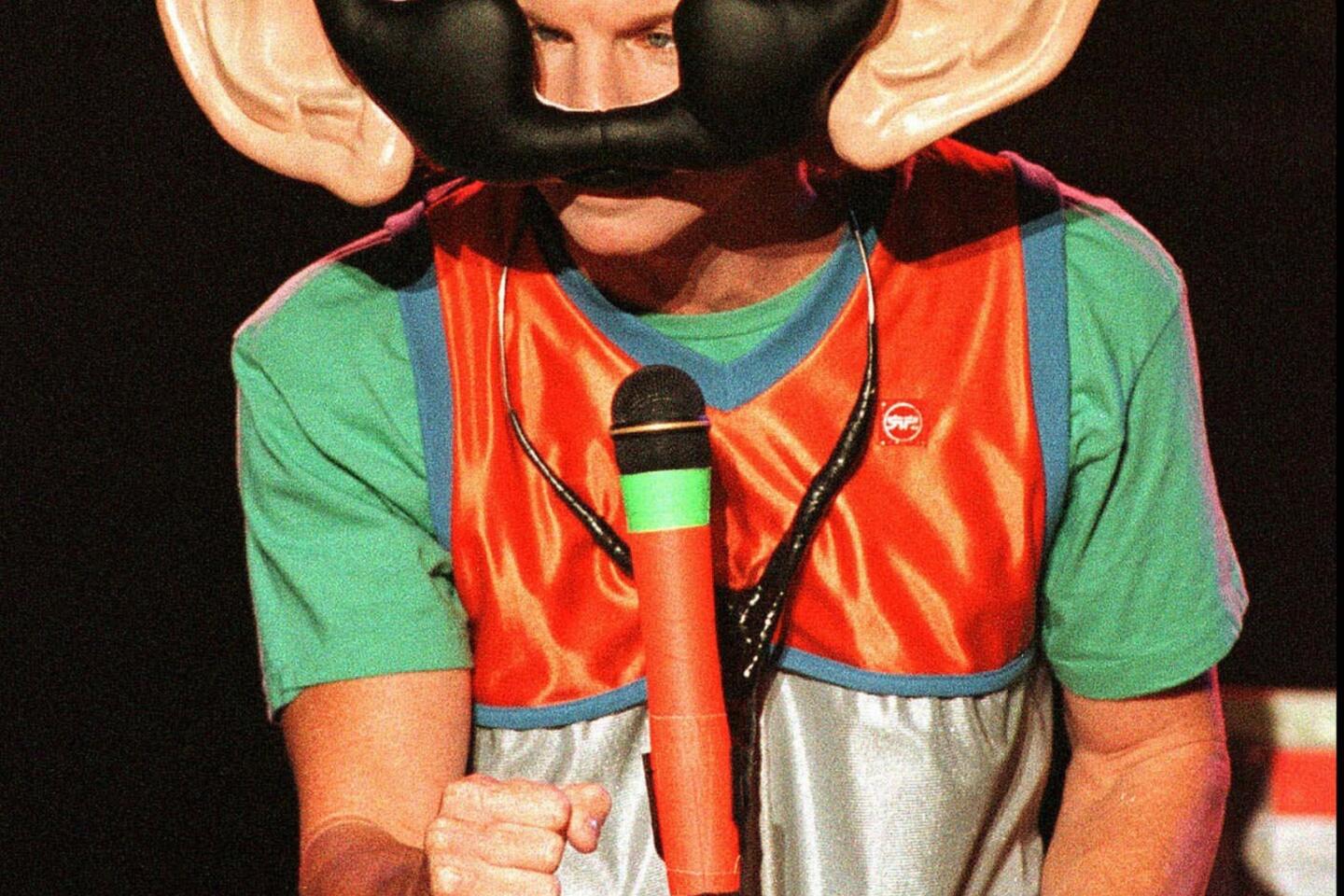

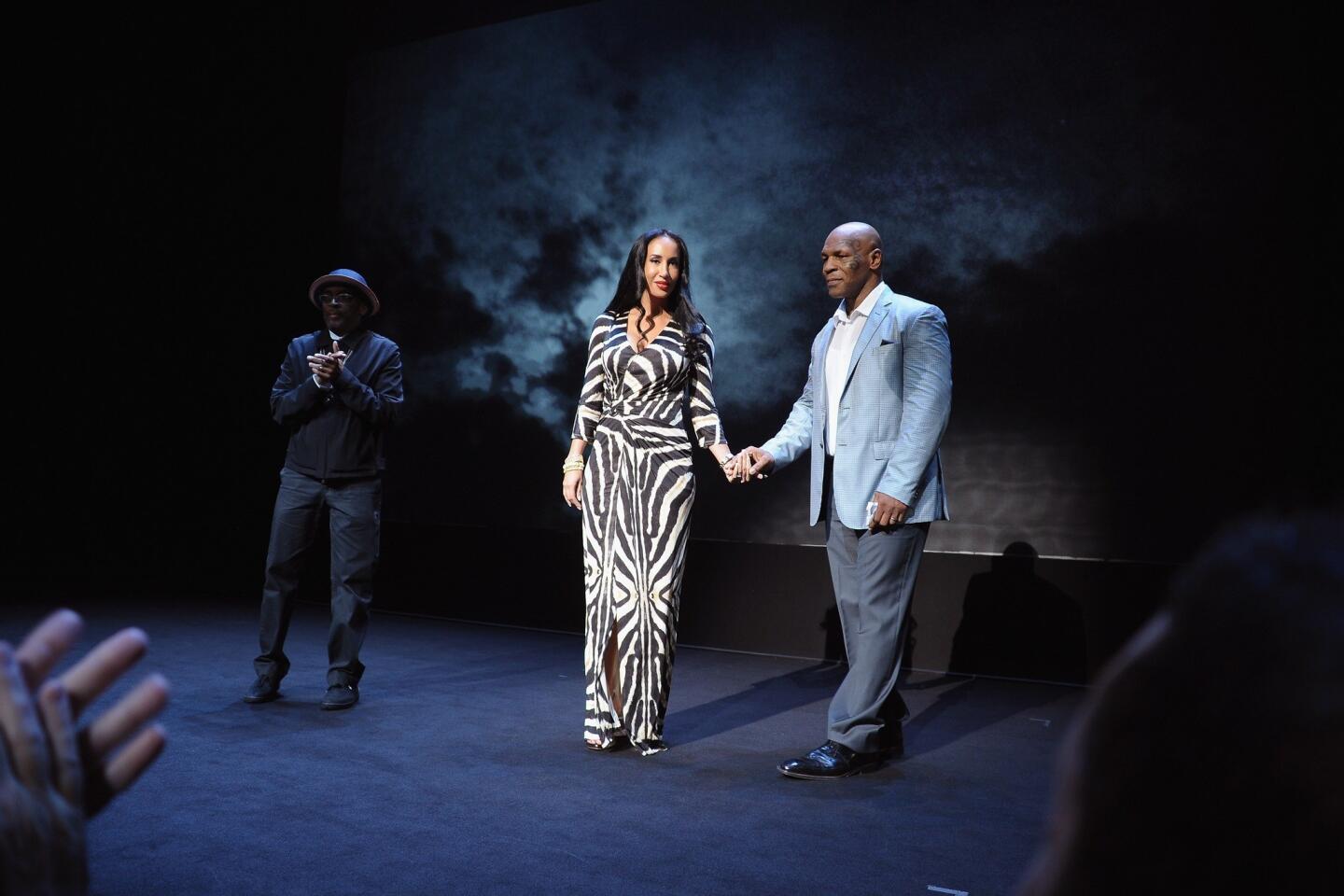

Directed with finesse by filmmaker Spike Lee and written by Tyson’s wife, Kiki Tyson, the production is more of an autobiographical show-and-tell with video backdrop than an apology tour. A rebranding campaign is obviously underway at financially strapped Tyson headquarters, but the compassionate context that’s provided for this recovery tale isn’t misplaced.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

An early photo of a white mother and her baby are projected in place of the baby pictures that weren’t taken when Tyson was born. Tyson palms this off as a joke by Lee, but it’s a poignant indication of the deprivation that marked Tyson’s Brooklyn childhood.

Tyson tells us that his mother, a “country girl” at heart lost in the inner city, drank to ease the pain and that for a long time he was confused about the identity of his real father. Living in drug-infested, crime-ridden neighborhoods (his family moved from hell to the devil’s toilet is how he characterizes it), Tyson developed a reputation as a street fighter. At 10, he was battling bullies who traveled to his block to take him on. Beating the daylights out of people gave him his identity, his self-respect.

Juvenile detention led to boxing mentors, who could see at a glance that those metal fists of his were being wasted in alleyways. His life was eventually changed by boxing manager and trainer Cus D’Amato, who became a surrogate father to him and got him to take his athletic talent seriously. At one time he was on the fast track to a lifetime behind bars; instead he became the youngest boxer ever to win the WBA, IBF and WBC titles. Fame and fortune followed, and that’s when a new set of troubles began.

Tyson recollects his scandals with a tranquillity that thankfully doesn’t dilute the absurdity. He’s found sobriety, but he hasn’t undergone a personality transplant. His own outrageousness leaves him slightly awe-struck. He knows he’s a character, and while he may be too old and tired at 46 to play the tabloid clown, he appreciates that some of his antics are hilarious (as well as potentially lucrative) in the retelling. After bankruptcy, a media pariah with a loyal fan following needs to think outside the box.

His relationship with actress Robin Givens naturally gets its own section. To call their divorce messy would be like calling World War II noisy. Tyson reveals that the two were regularly sleeping together even as their lawyers were battling. He recalls the time he caught Givens with a young Brad Pitt and the deep confusion he felt over whether to beat this pretty boy to a pulp or — how shall I delicately put this? — brutally make love to him.

PHOTOS: Mike Tyson in pop culture

Tyson acknowledges that much of this autobiographical material was surveyed in the 2008 documentary “Tyson,” but he says his recovery has given him new clarity. He’s a vegetarian now, but Iron Mike isn’t exactly donning a Buddhist monk’s robe. When he recounts the story of his infamous brawl with Mitch Green at the Harlem clothing store that dressed rap’s royalty, he conveys regret for having been drawn into this altercation, but he also takes a coroner’s delight in detailing what happened to Green’s face.

His sorriest emotions are reserved for family members who have died — his mother who didn’t get to see all that he achieved (and subsequently trashed), his beloved sister who was a light in the darkness of his early years. A devoted father who is proud that his kids correct his misspellings when he texts them, Tyson remains visibly heartbroken over the 2009 accidental death of his 4-year-old daughter.

He doesn’t whitewash his bad behavior, but he’s better at taking blame for general situations than for specific ones. He’ll happily inventory the 1,001 ways impulse control isn’t his strong suit, but he feels the need to remind us that when he bit a piece of Evander Holyfield’s ear off, the two were in a fight, not sitting down to tea. As for his 1992 rape conviction, Tyson pleads not guilty, offering only his reduced sentence as proof.

The show, which was originally going to be titled “Boxing, Bitches and Lawsuits,” provides plenty of evidence of Tyson’s ongoing problem with women. To fix this will require more than rehab — he needs to be re-acculturated. He’s come a long way, but perhaps the next step in his recovery is the realization that while heavyweight champions may be undisputed, the truth is owned by no one, not even a guy with a story as hard-hitting as his.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.