Review: Wallis Annenberg Center in Beverly Hills off to a moving start

- Share via

No one should be surprised that the Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts, which began its inaugural season Friday night with an appearance by the Martha Graham Dance Company, is a high-end venue. It’s in Beverly Hills.

A pop-up Salvatore Ferragamo store is its first attraction, just in case you find that your shoes suddenly feel out of fashion for the promenade from the entrance in the historic post office and past impressive donated contemporary art to the new Bram Goldsmith Theater. The catering (far finer and more reasonable than Patina at the Music Center) and the inviting indoor-outdoor lobby are quality all the way.

Nothing is modest here. The proportions of the 500-seat Goldsmith are grand, with seats wide enough to be love seats for ultra-skinny Beverly Hills models. Legroom is more than ample. The rake is steep. The stage is wide and deep. This is not an intimate space, that’s for sure, but the first impression is that you couldn’t really ask for a better theater in which to look at dance.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

As for listening in a multipurpose venue meant to also serve theater, music and opera, that will have to wait. The Graham company, unfortunately, used prerecorded music, so nothing much could be learned of the acoustics other than that the display of luxury stopped short of the sound system.

Opening with an 88-year-old dance company, which has remarkably managed to survive considerable crises since Graham’s death at age 96 in 1991, was an oddity.

The rationale was that Graham has a notable connection to Los Angeles, if not quite to Beverly Hills. Born in Pennsylvania, she moved to L.A. in her teens and studied at the pioneering Denishawn School on the edge of downtown. An exhibit about Graham in the Wallis lobby began by noting that, thanks to the school’s founders, Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn, modern dance was born in L.A.

But if that’s the case, then we can thank Graham for making sure that L.A. would not remain the seat of dance. As the evening’s program meant to reveal, Graham revolutionized dance once she set out on her own in New York in 1924 and broke away from the Denishawn exoticism by devoting herself to the expression of intense inner essence through wrenching outward movement.

Janet Eilber, the company’s artistic director and a former Graham dancer, began by using slides and film to help narrate Graham’s roots and development. There were excerpts and short dances by St. Denis (“The Incense”) and Shawn (“Gnossienne”). We saw a bit of Graham dancing Denishawn in the Greenwich Village Follies 1923-1925 — her first fame was in adding a dollop of high culture for the masses.

CHEAT SHEET: Fall arts preview

As the early music movement learned the hard way, recapturing history requires imagination, not attempts at slavish reproduction. Too many things have changed. For one thing, the bodies of today’s dancers are sculpted differently than those of a century ago. And then there was the sound. In re-creating “Gnossienne,” which had its premiere in 1919 in L.A., solo dancer Tadej Brdnik was undone by an unrealistically loud and distorted recording blasting an elephantine performance of Satie’s fragile piano miniature.

Can Graham’s breakthrough 1930 solo, “Lamentation,” her body contorted in tight burka-like costume as a study in the cathartic power of shape and movement, survive in the environment of an overly loud recording of Kodaly’s Piano Piece, Opus 3, No. 2? No, but Katherine Crockett made a noble attempt.

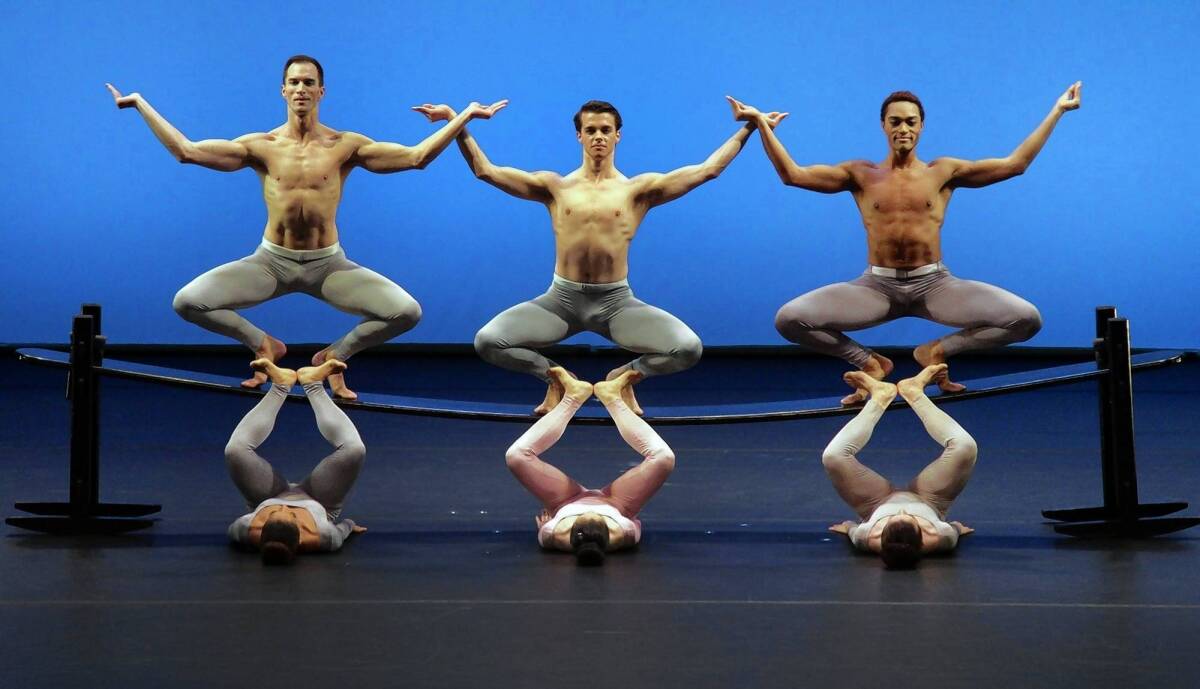

It was a huge jump over the years from the “Lamentation” solo to two late full company works, the stunning 1981 “Ritual to the Sun” from “Acts of Light” and Graham’s astonishing, playful last work, “Maple Leaf Rag,” from 1990. Both here looked great, especially “Ritual” in Beverly Emmons’ stunning lighting.

The modernity of the work, furthermore, made the recorded music (Nielsen’s “Helios” Overture in the former, Joplin rags in the latter) feel less anachronistic, if hardly ideal. These late works, playful and wisely self-aware, are dances of rejuvenation, still fresh and alive, needing not restoration but simply care and joy.

The revelation of the evening, though, was in the powerfully successful reconstruction of three sections from “Chronicle,” a 1936 feminist response to war for 12 women. Graham’s first real masterpiece, the dance begins with a solo lament with Blakeley White-McGuire convincingly conveying Graham’s physical contractions. It concludes with the dozen women, in stirring, defiant formations.

GRAPHIC: Highest-earning art executives | Highest-earning conductors

Impressively, the extraordinary performance was not, like the other, earlier reconstructions, dutiful. A lot of creative imagination clearly went into what amounts to restoring about half of the original work, which was described in a review of the 1936 New York premiere as nearly an hour of overlong, tortuous dancing. For the middle section, “Steps in the Street,” the company no longer uses Wallingford Riegger’s original score but his more famous (and perhaps more effective) “New Dance.”

Eilber introduced “Chronicle” by reading a thrilling letter Graham wrote to Hitler’s propaganda chief, Joseph Goebbels, refusing an invitation to take part in the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, protesting the Nazi persecution of artists.

But maybe Graham should have gone to Berlin after all and treated the Germans to her American Valkyrie spirit. She would surely have given German director Leni Riefenstahl something startlingly different to shoot for her Nazi propaganda films.

The Wallis has wrinkles to yet work out, and only time will tell about the acoustics, but it has, at least, with “Chronicle,” opened with an important statement.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.