‘We wanted to sing all along’: A new documentary seeks to reframe the Milli Vanilli controversy

- Share via

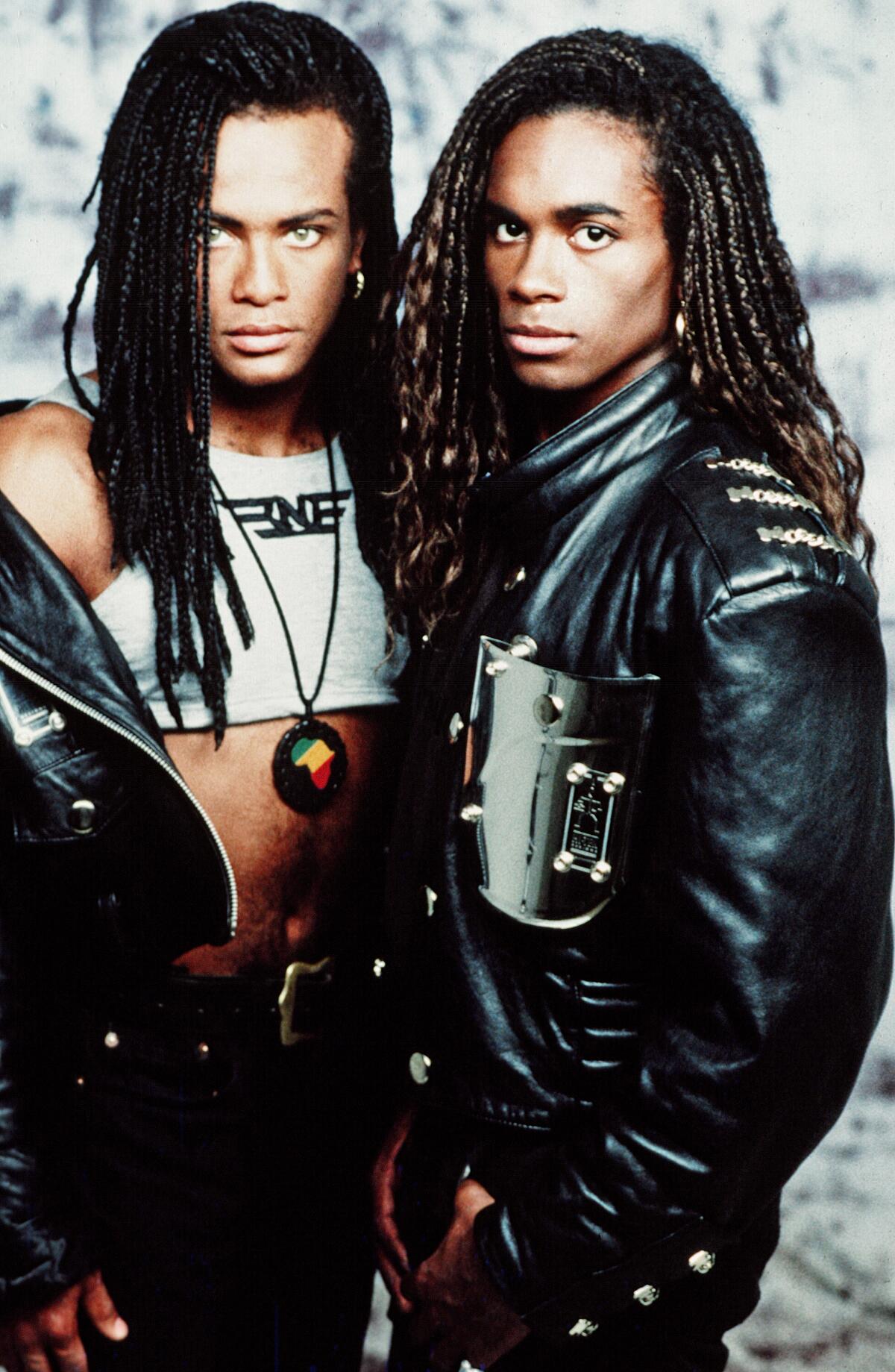

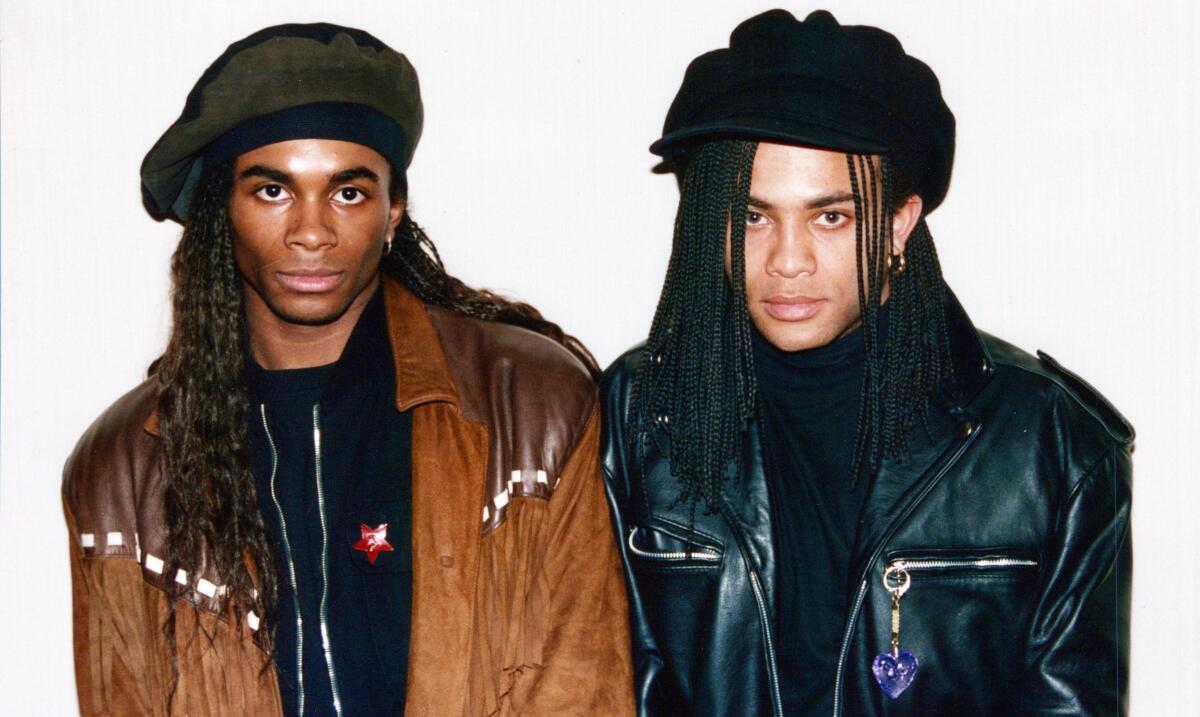

Before they became an international punchline, Milli Vanilli was one of the biggest pop acts of the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. Their North American debut album, “Girl You Know It’s True,” featured a distinct blend of R&B, rap and dance music, produced three No. 1 singles and sold more than 6 million copies in the US alone. With their striking looks and distinctive style — long braids, Spandex and broad-shouldered blazers — the duo of Fabrice Morvan and Rob Pilatus were telegenic stars tailor-made for the MTV era.

The problem, as the world eventually learned, was that they didn’t sing a single note on the album, and at concerts and live performances — including the Grammy Awards — were lip-synching to music recorded by other singers. The scheme was devised by German producer Frank Farian, who signed Morvan and Pilatus to a recording contract but used session musicians including Brad Howell, Charles Shaw and John Davis on the album. The ruse collapsed in November 1990 when Farian, angered that the duo wanted to sing on their next album, decided to out them as “impostors.” In a subsequent interview with The Times, Pilatus admitted the claims were true.”We are true singers, but that maniac Frank Farian would never allow us to express ourselves,” he said.

While Morvan and Pilatus bore the brunt of the vicious backlash that ensued, Farian and executives at record company Arista, including founder Clive Davis, escaped largely unscathed. The downfall was particularly devastating for the German-born Pilatus, who struggled with drug addiction and died of an overdose in 1998, at the age of 32.

The Milli Vanilli duo said today they made a “pact with the devil” when they pretended they sang on a hit album, and they contended it was all with the knowledge of their record company.

For the last 30-plus years, the Milli Vanilli scandal has been viewed as a semi-farcical cautionary tale about seeking fame at any price. But a new documentary reframes the ordeal as a tragic story about the exploitation of artists — particularly Black artists — in the music industry. “Milli Vanilli,” now streaming on Paramount+, features interviews with Morvan as well as several musicians who performed on the “Girl You Know It’s True” album, including Shaw and Howell, who have moved on from the controversy but still feel they were taken advantage of.

“It’s what I wanted for a long time — to tell my story. You knew the headlines, but you didn’t know the story,” said Morvan recently in a Zoom conversation from Majorca, Spain.

Clad in a denim vest with his dreadlocks piled atop his head, the singer — yes, he does sing — looked scarcely older than the performer who bumped chests with Pilatus in the “Girl You Know It’s True” video. “What I want people to know is that during this whole process, we wanted to sing all along,” he said. “We just fell into this whirlwind and this dream/nightmare. None of this was premeditated.”

“We remember this story so wrong, I think partially because we want to,” said director Luke Korem. “It seems like we know the sensational headlines. I wanted to tell a very personal journey about Rob and Fab but also the real singers, like Charles Shaw.”

“I hope that people don’t think of these guys as a joke anymore,” he added.

The filmmaker became interested in the subject after watching a video of Morvan performing at the Moth, a storytelling event in New York.

“I could tell he had put this behind him in a way I found really amazing,” he said. “But then at the end, he sang and he had this wonderful voice and I thought, ‘Wait a minute. I thought [Milli Vanilli] was these two guys with no talent who conned everybody. Why would this guy ever agree to lip sync? And that’s what led me down a rabbit hole.”

He spent a year convincing a wary Morvan to participate because, without him, “There was no documentary.” Nearly everyone else involved was reluctant to participate, but Korem eventually won over most of the key players, including Shaw, Howell, backup vocalists Jodie and Linda Rocco, and Ingrid Segieth, Farian’s ex-girlfriend and assistant. “I went to every person involved and said, ‘I want to hear your truth even if it conflicts with someone else.’ ”

Another key element was an audio recording of an interview Pilatus gave during a stay at a rehab clinic a few weeks before his death, which “brought Rob’s spirit alive,” said Korem, and brought his perspective into the story. “He was very clear and his words are very powerful and haunting at times.”

The story begins in 1980s Munich, where Pilatus, who was raised by his adoptive family in Germany, and Morvan, who is originally from France, met, formed a fast friendship and began performing together. Young, broke and eager to make it, they hastily signed a contract with Farian, one of the most successful music producers in Germany at the time, without giving it a second thought — or even reading it. However, they soon learned that he only wanted them to lip-sync songs performed by other people and was more interested in their unique look and dancing skills than whatever musical abilities they may have had. Fearing the financial and legal consequences of breaking the contract, they went along with the scheme.

The problem was that Milli Vanilli’s debut single, “Girl You Know It’s True” unexpectedly blew up, becoming a top 5 single in 23 countries. Then came the album, which included several other chart-topping hits, including “Don’t Forget My Number” and “Blame It on the Rain,” written by Diane Warren. Morvan and Pilatus became international superstars whose thick accents and halting English aroused suspicion. As their fame grew, so did the pressure to keep the secret — and the inevitability that the truth would come out.

“We embraced the lie because we didn’t know any better,” said Morvan. “It was exciting. Love was not prevalent or even existent in our backgrounds. So when we experienced this love from the audience, it was amazing. The dream was always to become singers, songwriters, producers, performers. People think we were the ones orchestrating everything when in fact we fell into a trap, signed a contract with no attorney, no management, no protection.”

Shaw is an American from Houston who had been working as a musician in Germany for years when Farian hired him to perform the rap vocals on the single “Girl You Know It’s True” and ordered Shaw to keep his mouth shut. “He said, I’ve got two guys that are gonna front it. You just keep your mouth shut,’” recalled Shaw. Farian replaced Shaw before recording the album because he believed the vocalist was telling people the truth about Milli Vanilli.

“The contract that he did was a dirty deal,” Shaw said by phone from Germany, where he continues to perform with his group, the Classic Brothers. “‘Girl You Know It’s True’ sold god knows how many millions. Everybody’s talking about these two guys. What about the voices that was in the back? Right? What about the voices that did the work?”

Shaw was never able to secure a major contract with another label in Germany, and he believes he was blacklisted by the producer. “This is one of the biggest producers in Germany and Europe. You think they’re gonna listen to the little Black guy coming out of Texas?” he said.

The documentary also raises questions about how much Arista knew about Farian’s scheme. The European version of Milli Vanilli’s album — known as “All or Nothing” and released prior to the American version — listed credits for Shaw and other vocalists, but not Morvan or Pilatus. The duo was also allowed to lip sync their performance at the Grammys in 1990, where they won new artist over acts such as the Indigo Girls.

“I find it funny how to this day — hopefully this documentary changes things — how people have just given Clive Davis a free ride on this,” said Korem. “There’s a bunch of white people that made the lion’s share of the money. And then the people like Rob, Fab, Charles — they got kicked to the curb.”

“Milli Vanilli” depicts Farian as a Svengali-like figure who treated Black artists as easily replaced cogs in his hit-making machine and also had a track record for recording studio chicanery dating back a decade before Milli Vanilli’s debut. The film revisits his history with the disco group Boney M. — known for their eccentric hit single “Rasputin” — whose Black frontman, Bobby Farrell, did virtually no singing on their records. (Farian sang his parts.)

“Seeing how he repeated [himself] was very disturbing,” said Korem.

“Milli Vanilli” explores the ugly backlash that was largely directed at Morvan and Pilatus, rather than people like Farian. It includes a brief clip of a blackface sketch from “The Howard Stern Show” and footage of a press conference in which the duo was angrily berated by reporters. Many fans also joined a class-action lawsuit against the group.

Korem believes that the controversy — and the vitriol it unleashed — “100% contributed to Rob’s death.” Morvan also thinks that his partner “died of a broken heart because it was rough. The jokes were bad” and the label “threw us to the wolves.”

Morvan suspects he was able to weather the storm better than his partner because he never fully came to believe the lie. “We were different emotionally. He didn’t see it coming. I saw it coming.”

Morvan was slowly able to rebound, working as a French teacher for a time to make ends meet but always focusing on music. Now a father of four, he continues to perform — including songs by Milli Vanilli. He only betrays a hint of anger when talking about the continued use of his image in association with the group. “After 30 years now, my likeness is still being used. I don’t see a cent. They’re still exploiting my image,” he said.

“The reason why I’m still here is because of my love for music and my passion for music. I never let up.”

Likewise, Shaw has gained perspective on the Milli Vanilli debacle over the years, and now feels empathy for Morvan and Pilatus. “I respect them for what they did. And I feel with them for what they went through,” he said.

But he also feels shortchanged — denied the credit, not to mention the money, he was due long ago.

“I’m not asking for a Grammy. I’m not trying to say I’m the best,” said Shaw, “but if it wasn’t for my voice, there would be no Milli Vanilli.”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.