Review: ‘Transatlantic’ is a clunky, quasi-historical melodrama about Varian Fry

- Share via

The story of Varian Fry, the Emergency Rescue Committee (later to become today’s International Rescue Committee) and its efforts to spirit refugee artists and intellectuals out of Vichy France in the early years of World War II has become a historical, ahistorical, quasi-historical romantic melodrama, “Transatlantic.” Written by Anna Winger (“Unorthodox”) and Daniel Hendler, and premiering Friday on Netflix, the seven-episode series was “inspired by,” though not adapted from, the 2019 novel “The Flight Portfolio,” in which author Julie Orringer imagined Fry’s life as a closeted gay man. It’s a storyline here, along with other tales of love in a time of fascism, whose heroes get up close and personal while handling collaborationist French policemen, obstructive American bureaucrats, unpredictable border guards and difficult creative types.

In a note to the press, the IRC, evidently both flattered to be noticed and concerned that a viewer might mistake “Transatlantic” for a straightforward recitation of the facts, pointed out, in boldface, that the account was “fictionalized.” While true to the essence of the story, with sundry facts pinned to the dialogue, the series rewrites many particulars and creates or alters events and characters in the service of a conventional brand of screen excitement — though the actual facts of the case, widely available in print and online, are dramatic enough.

I first became aware of Fry and the ERC from Ken Burns’ documentary series “The U.S. and the Holocaust,” and, as someone interested in that intersection of political, cultural and art history, I was excited to see this. (It’s not every TV series, or any other TV series, that has Max Ernst as a character.) You can’t blame filmmakers for not making the work you imagine. Though “Transatlantic” is made with evident affection for its subject, and is not without entertainment value, it can also be clunky, corny and clichéd, scattered and perfunctory and at times unintentionally laughable.

Many characters share the names and attributes of actual people, but whether somewhat real or entirely fictional, they mainly serve at the pleasure of the screenwriters, delivering exposition, trivia and philosophy, engaging in acts of derring-do and intimate clinches, moving the story along without becoming full-bodied people. (Given their cardboard nature, it’s the villains, such as they are — Corey Stoll as the unhelpful American consul and Gregory Montel, an amalgam of generations of French movie police chiefs — who seem to be having the best time.)

Filmmaker Ken Burns’ latest documentary series, ‘The U.S. and the Holocaust,’ draws parallels to the recent rise in American nationalism and antisemitism.

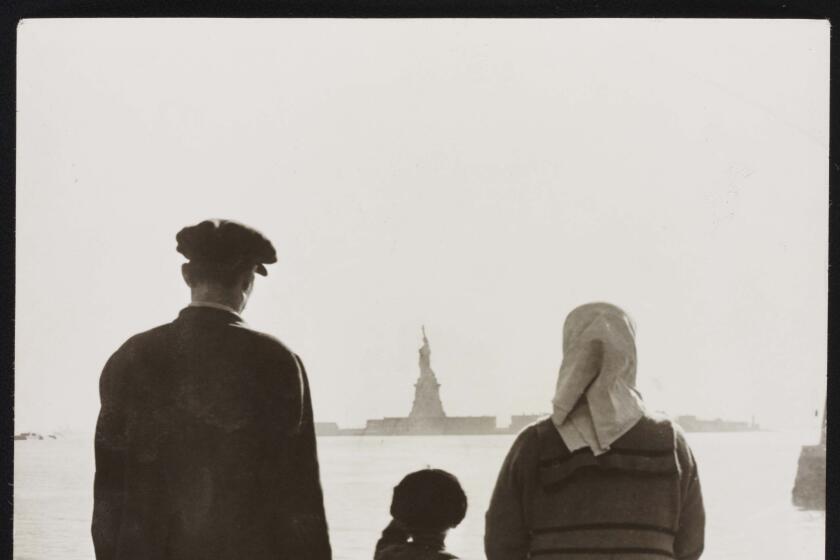

Fry (Cory Michael Smith), an American journalist who had reported from Berlin on the persecution of the Jews when the U.S. could barely be bothered to cluck its tongue, was only 32 when, in 1940, he went to Marseille to run the ERC, a group he co-founded with the encouragement of Eleanor Roosevelt. Ostensibly (and partially) a relief organization, in the 13 months before Fry was kicked out of the country, it helped some 1,500 refugees — not all of them cultural VIPs, many of them Jews — leave France, often by extralegal means, some by ship, others on foot to Spain over the Pyrenees, which in the series’ fuzzy geography seem a stone’s throw from Marseille. (They’re not.) Assistance was provided to thousands more.

But in this telling, Fry comes across as not just inexperienced but insecure: wet behind the ears, a little timid, wary of crossing lines. It’s his colleagues who encourage risk-taking, law-bending and clandestine ops, most notably top-billed Gillian Jacobs as Mary Jayne Gold, an American heiress living in France who fell in with the ERC (and is the subject of another work of historical fiction, Meg Waite Clayton’s “The Postmistress of Paris”). Here, she’s a driving force — at times the driving force — a plucky, All-American gal game to do anything to help those in need.

“That is settled then,” declares Mary Jayne, after Fry’s justice league has suddenly grown by two new members, the refugee smuggler Lisa Fittko (Deleila Piasko) and Albert Hirschman (Lucas Englander), a dashing, daring economist seemingly conflated with Raymond Couraud, Gold’s underworld-connected real-life lover, who would become a much-decorated war hero. “Varian, you remain the face of the operation; Lisa, you are the muscle; Albert’s definitely the criminal … I’m just the bank” — at which self-deprecating remark Mary Jayne is told she’s being too modest. Later, another character will point out — as if arguing for Gold’s centrality in the series — that as a woman, Mary Jayne knows what it’s like to downplay her presence, accomplishments and intellect, and so she already has what it takes to make a spy.

It’s a mishmash. On the one hand, it’s a multilingual, multicultural, international adventure. On the other, it’s an earnest lesson in history — that thing we must learn from or else repeat — addressed not just to the period, but the period we’re living in. We meet a representative from a company not called IBM, but it’s most definitely IBM, who represents capitalists happy to do business with fascists. Paul (Ralph Amoussou), the Black concierge at the Hotel Splendide — where the ERC and various refugees are housed before moving out to the Villa Air-Bel — dreams of taking the fight for freedom back home to Dahomey after the war. (“You’ve never come face to face with your oppressor before, have you?” he asks Albert, who has just crossed paths with a Nazi officer. “For me it happens every day.”) The description of presidential candidate Wendell Willkie as a businessman who’d never held public office feels pointed at our current political scene, as is the reply of vice-consul Hiram Bingham (Luke Thompson), as generous in providing visas as his superiors were loath to issue them, when asked the meaning “electoral college”: “I would explain it to you. But you’ll never understand it, because it doesn’t make any sense.”

On the art-history side, there’s something sort of delightful — even when it feels silly in the execution — about a series in which a character can announce, of an arriving couple, “It’s the Chagalls.” It might help to know something about 20th century European art and philosophy going in, why the people represented here — including Ernst (Alexander Fehling), André Breton, Walter Benjamin and Hannah Arendt — are important, or even what their art was like. The informed may spot the references: the Jeu de Marseilles deck of cards produced by artists sheltering and partying at the Villa — here the property of Thomas Lovegrove (Amit Rahav), an original character who serves double duty as Varian’s former lover and Mary Jayne’s conspirator in some extracurricular espionage — as well as Hans Bellmer breaking up baby dolls for his erotic sculptures and a game of “exquisite corpse.” A madcap Peggy Guggenheim (Jodhi May), of the art-collecting Guggenheims, puts in an appearance.

And, of course, the series as a whole shines a light by association on the ongoing plight of refugees, on resurgent nativism and antisemitism, and the deaf ear we are liable to turn to any crisis not literally on our doorstep. “Transatlantic” may not be the most effective translator of these issues, but neither does it demean them. And that light can’t shine too often.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.