How a new wave of Native stories took a ‘sledgehammer’ to Hollywood’s closed doors

- Share via

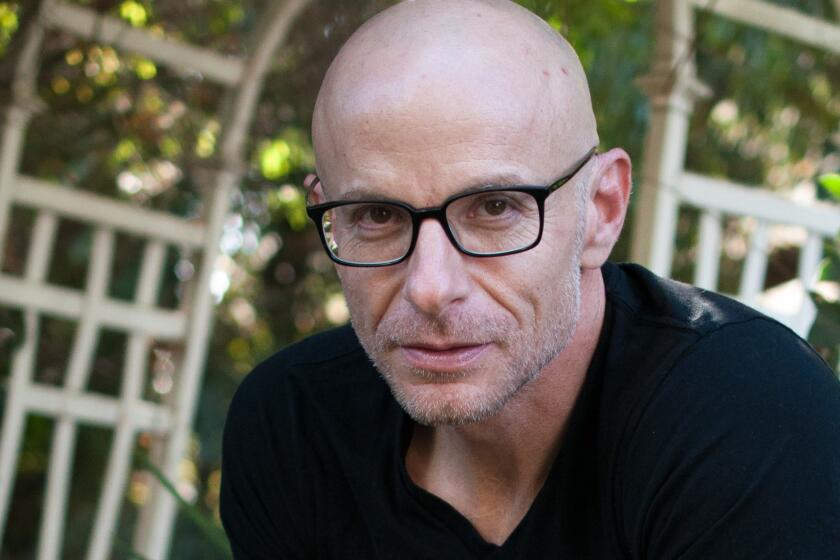

Three-decade stage and screen veteran Michael Greyeyes cemented a new phase of his artistic life this year when his acclaimed performances on Peacock’s sitcom “Rutherford Falls” and in the thriller “Wild Indian” landed mainstream attention and awards laurels, including career-first double Gotham Awards acting nominations in both film and television categories.

As tribal casino boss Terry Thomas in “Rutherford Falls,” set in a fictional American town confronting its own colonialist history, the Nêhiyaw actor and theater director from Muskeg Lake Cree Nation in Saskatchewan, Canada, brings depth and pride to a type of figure often shallowly defined in narratives involving contemporary Native characters.

In “Wild Indian,” arguably his darkest turn yet, he lends nuance and pathos to a portrait of generational trauma as Makwa, an Anishinaabe man hiding his true self and an abusive childhood behind a veneer of success.

On paper, the characters would appear to be polar opposites. “But the view from the inside is actually that they’re incredibly similar,” said Greyeyes, 54, “in that these characters afforded me a chance to be challenged in ways that I as an artist have not been asked to challenge myself.”

Peacock’s “Rutherford Falls” stars Ed Helms as a good man with a big blind spot: He believes history is to be celebrated rather than examined.

In Hollywood, Indigenous artists have been fighting invisibility, misrepresentation and erasure on screen for over a century, and even recent industry statistics indicate not much has changed. UCLA’s 2021 Hollywood Diversity Report found that in the 2019-2020 season, not a single broadcast, cable or digital scripted show featured a Native person in a lead role; across the top films of 2020, Native actors constituted only 1.1% of leads.

By comparison, 2021 has witnessed important strides in Native-led storytelling in TV and film: In addition to “Wild Indian” and “Rutherford Falls,” there’s FX’s wry dramedy series “Reservation Dogs” and indie films like Tracey Deer’s Oka Crisis coming-of-age tale, “Beans,” and Danis Goulet’s sci-fi allegory, “Night Raiders,” starring Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers.

This outpouring has sprung from unprecedented opportunities for Indigenous talent in front of and behind the camera. Instead of stereotypical, historically romanticized or vilified characters and one-dimensional tropes, the new wave features complex Indigenous protagonists from different communities and cultures; rather than being sidelined in support of non-Native leads, they are the centers of their own narratives.

It’s no coincidence that these projects hail from Indigenous creators, with two of the season’s breakout TV hits boasting Native cast, crew, writers and directors and led by Native showrunners: Sierra Teller Ornelas, co-creator of “Rutherford Falls” with Ed Helms and Michael Schur, and Sterlin Harjo and Oscar-winning “Jojo Rabbit” filmmaker Taika Waititi, co-creators of “Reservation Dogs.”

“It’s beautiful to show Native people in a contemporary way, like we exist and are multifaceted,” said Leah Salgado, chief impact officer at IllumiNative, a nonprofit that works to increase visibility for Native peoples in American society. “‘Rutherford Falls’ and ‘Reservation Dogs’ are two very different looks at Native communities. Both are incredibly valid and show a range that we have not seen before. ... We can only show that complexity because there were Native creators in the writers room and helming the show.”

The difference that authentic voices bring to these narratives is undeniable, says Mohawk actor, filmmaker and activist Devery Jacobs, who admits to feeling uncertain about her career before being cast in “Reservation Dogs.”

Even after an acclaimed star turn in Mi’kmaq filmmaker Jeff Barnaby’s 2013 drama “Rhymes for Young Ghouls,” which earned her a Canadian Screen Award nomination, and appearances on Starz’s “American Gods” and Netflix’s “The Order,” opportunities to play characters she felt defied shallow stereotypes remained few and far between. On auditions, she was made to feel that certain attributes that tied her to her community, like her accent, would prevent her from a successful career.

“I quickly learned that working with Indigenous creatives at the helm of a project was actually the exception instead of the norm,” said Jacobs, 28.

“It’s not like we’re underrepresented, we’re not represented,” says Ojibwe author David Treuer, who is joining Pantheon to edit emerging writers.

But in “Reservation Dogs’” tenacious Elora Danan Postoak, one of a group of teen misfits growing up on a rural Oklahoma reservation inspired by Seminole and Muscogee (Creek) showrunner Harjo’s upbringing, she found qualities she recognized from her own experience growing up in Kahnawà:ke Mohawk Territory in Quebec, Canada. Over the course of the show’s debut season, she peeled back Elora Danan’s exterior to reveal the hurt and heart driving her to leave her community and head West — with or without her friends, as the season finale teased.

“Devery brought a layer to it that wasn’t on the page,” said Harjo. “Elora Danan could have been looked at as just a tough girl and that’s it, and I think that’s what a lesser actor would have portrayed. But there’s so much going on in her eyes and so much that’s not said in her performance, which is crucial because that character is dealing with a lot of internal things.”

The performance landed Jacobs a Gotham Awards nomination for outstanding performance in a new series alongside Greyeyes (with whom she also appeared on “Rutherford Falls” as Terry’s flighty assistant, Jess, and before that in Barnaby’s 2019 zombie action picture “Blood Quantum”). The series, which won the Gotham Award for breakthrough series — short format, also snagged a Critics Choice nomination for best comedy series.

Last year, while filming the pilot, Jacobs realized the mostly Indigenous cast and crew were tapping into something special as a scene called for the eponymous squad of teenage rebels — including D’Pharaoh Woon-A-Tai as Bear, Paulina Alexis as Willie Jack and Lane Factor as Cheese — to mark the one-year anniversary of their friend Daniel’s death.

The sense of loss felt all too familiar to many on set; Indigenous people in North America die by suicide at a higher rate than other racial or ethnic groups, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Statistics Canada. But the communal support and healing were just as palpable.

Episode 7, “California Dreamin’,” which flashes back to explain how deep Elora Danan’s grief over Daniel’s death runs, “was incredibly challenging and also triggering” to film, said Jacobs. Written and directed by Tazbah Rose Chavez and described by Harjo as “the Elora Danan episode,” it was accompanied by a smudging ceremony, sensitive conversations and prayers on the day of filming to ensure the subject matter and mental health of the cast and crew were protected.

“I had never experienced an opportunity for us to collectively mourn and heal and celebrate while filming a project before, surrounded by community,” said Jacobs. As filming on the debut season wrapped, she found herself in tears, “because I realized just how much I had been craving an experience like that before.”

The new comedy, set on an Oklahoma reservation, uses its rich, highly specific sense of place to offer a refreshing take on contemporary teen life.

In Greyeyes’ case, working with Indigenous creatives on “Wild Indian” and “Rutherford Falls” — “pinnacles of my career at this point, projects that are actually life-changing” — allowed him to trust that the storytelling would be balanced, freeing him to explore new and at times complicated terrain within himself as a performer.

In the former, he and Chaske Spencer play Makwa and Ted-O, respectively, two Anishinaabe men linked by a brutal act of violence. Knowing that director Lyle Mitchell Corbine Jr. would temper his character’s darkness with Spencer’s vulnerability meant “I could lean in completely to his self-loathing and his anger, and that wouldn’t be the only reading that audiences were allowed in terms of our culture,” said Greyeyes.

Thanks to the pandemic, he had only a week after finishing pickups on “Wild Indian” to jump into the mindset of “Rutherford Falls’” Terry Thomas. Portraying the polished family man and CEO of the fictional Minishonka tribal casino, who makes an intimidating impression on heroine Reagan Wells (Jana Schmieding), involved a radical shift. Peacock renewed the series for a second season in July.

“He is filled with the joy of being Native and being from strong communities,” said Greyeyes. “When I started playing Terry, it was jarring because no trauma was present in the writing. We were being asked by Sierra [Teller Ornelas] and the writers and the other producers to stand on firm ground and emit joy and emit power, but without any of the trappings that Hollywood’s used to or that American audiences are used to — that we were used to.”

Teller Ornelas describes what made Greyeyes, whom she calls “Native actor royalty,” the only actor who could deliver Terry’s monologues and bring humor and humanity to his quest to build a thriving future for his community.

“He just had this incredible cadence and demeanor,” said Teller Ornelas, who is Navajo and Mexican American. “People think I’m crazy, but he read it, and it reminded me of Barack Obama. There was a grace and humility, but also strength and power and real intimidation, dancing back and forth between those two ideas.”

Building the character, they discussed Terry’s “hyperawareness” of how he is perceived as a Native man in Rutherford Falls, a thread that stretches across the season but is especially highlighted in the episode “Terry Thomas,” in which the character pauses an interview with a white NPR reporter to deliver a showstopping monologue about his approach to tribal legacy and capitalism.

“I think there’s a lot of power to a character who is unapologetically Native and unapologetically inhabiting the space,” said Teller Ornelas. “To watch him do that with a wink and still be funny and still be not infallible, but aspirational in a really wonderful way ... it’s a real high-wire act.”

Even as their work is met with awards and acclaim, both Greyeyes and Jacobs express the bittersweet twinge of being recognized with honors when so few of their predecessors were acknowledged.

Holding his phone up to the video chat lens, Greyeyes shows off a sticker by Indigenous artist Gregg Deal depicting Wes Studi‘s Magua in “The Last of the Mohicans.” “I look back on the people who are my heroes, like Gary Farmer, Sheila Tousey, Chief Dan George, Gordon Tootoosis, Augie Schellenberg, Tantoo Cardinal — all these people that have had extraordinary careers,” he said, adding Studi and Will Sampson in “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” to the list. “These are [performers] I idolize, and these people should have won Oscars.”

“I recognize that we’re trying to turn this massive ship, and massive ships don’t turn easily,” continued Greyeyes, whose upcoming films include director Bretten Hannam’s indie drama “Wildhood,” about a two-spirit Mi’kmaw teenager. “And there’s a few of us pushing against the hull, moving it towards work and achievement that are erased or ignored or simply unseen.”

Producers must identify as Native and be attached to a current project to qualify for Netflix’s IllumiNative Producers Program. Here’s how to apply.

A similar instinct drives Jacobs — who has directed short films inspired by Canada’s epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women, as well as her mother’s childhood — to continue to develop passion projects that reflect her experience as a queer Indigenous artist. Adding to her behind-the-camera résumé, she also joined the expanded “Reservation Dogs” writers room for Season 2, which she and Harjo say will broaden the scope of the show and its characters.

Meanwhile, cognizant of how creatives like Teller Ornelas kicked Hollywood’s door open to more new and emerging talent, Greyeyes started making his own moves. After starring for Blumhouse Productions in the upcoming Stephen King remake “Firestarter,” Greyeyes inked a first-look deal with the company in August to develop his own projects as writer and director. His goal is to bring fellow Native artists and performers the kinds of opportunities they’ve never been granted before.

“What I’m hoping is, if I’m allowed through a door, the first thing I’m going to do is get out a screwdriver and a pry bar and tear the hinges off the door,” he said. “Maybe you get a sledgehammer and just open up the doorway a bit wider.”

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.