They weren’t superstars. But Tommy Kirk and Sam Riddle defined ’60s Hollywood

- Share via

Two midcentury pop cultural figures passed away last week; neither was a superstar by objective standards, but if you were young or even not so young at a certain time and place, you might well have looked at them that way.

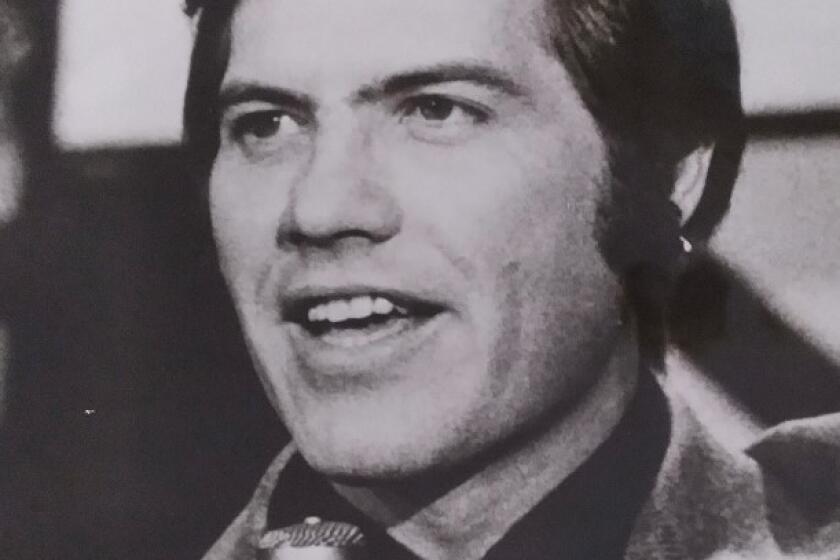

Tommy Kirk, who died Sept. 28 at 79, was a Disney boy-next-door type before Kurt Russell was a computer who wore tennis shoes or Justin Timberlake did whatever he did on whatever iteration of “The Mickey Mouse Club” he was on. Kirk was clean-cut, in the mid-’50s to early ’60s mold, but he was more Ricky than David Nelson, if that makes sense to you. That is to say, his characters were often unconventional for the times, in ways that were still acceptable for a Disney film. If you were a kid, he just seemed cool, but the sort of cool kid you could imagine yourself becoming. And the Disney image notwithstanding, there was room for complexity in its moral universe; Kirk never seemed simple or saccharine.

His Disney films include “Swiss Family Robinson,” “The Shaggy Dog,” “The Absent-Minded Professor” and its sequel, “Son of Flubber,” “The Misadventures of Merlin Jones” and its sequel, “The Monkey’s Uncle,” “Babes in Toyland,” “Bon Voyage!” and a pair of films originally made for television, shot overseas and co-starring Annette Funicello: “Escapade in Florence” and “The Horsemasters.” He was Joe, the younger and more intriguing of the Hardy Boys, in a couple of “Mickey Mouse Club” serials.

Pleasantly handsome, he could play both leads and character parts, though his leads usually had a bit of the character actor, and his secondary roles tended to make a bigger impression than the headliners. As toymaker Ed Wynn’s inventor assistant in “Babes,” it’s Kirk, and not star Tommy Sands, you want to watch. (Kirk often played characters with a bent for invention, including in “Swiss Family Robinson.”) His strong suit was comedy, for which he had a light, lively touch, but he was also the dramatic linchpin of “Old Yeller,” a western drama about a good dog the mere passing thought of will have me weeping before I finish typing this sentence.

Tommy Kirk, a child star who played in Disney films such as “Old Yeller” and “The Shaggy Dog,” has died.

Later, like Funicello, he transitioned into surf comedies — “Pajama Party,” “It’s a Bikini World” — before downshifting into mockable sci-fi and horror films, including “Village of the Giants” and “It’s Alive!” His acting career was effectively over by the mid-1970s.

This was not a matter of talent. Kirk was gay, and in 1964, when threatened with it becoming public, Disney fired him — though they brought him back for “The Monkey’s Uncle” after “Merlin Jones” proved a box-office success. He had problems for a time with substance abuse; one might reasonably speculate that the drugs were in some way a result of the firing. But, in interviews at least, Kirk almost never casts blame; when he talks about the direction of his career or conflicts with co-stars, he seems always ready to take the long view, to thoughtfully examine how things were with him in the time when they occurred. He was named a Disney Legend in 2006 and would show up for fan conventions.

As with many good actors who disappear from view long before they leave the world, it’s perhaps too easy to play the game of “What if?” and to feel, on their behalf as well as our own, a sense of disappointment; one doesn’t really want to project disappointment onto another person’s life. But there’s more to life than being in the movies. One only hopes he was happy at last, and, happily, I haven’t seen anything to suggest he wasn’t.

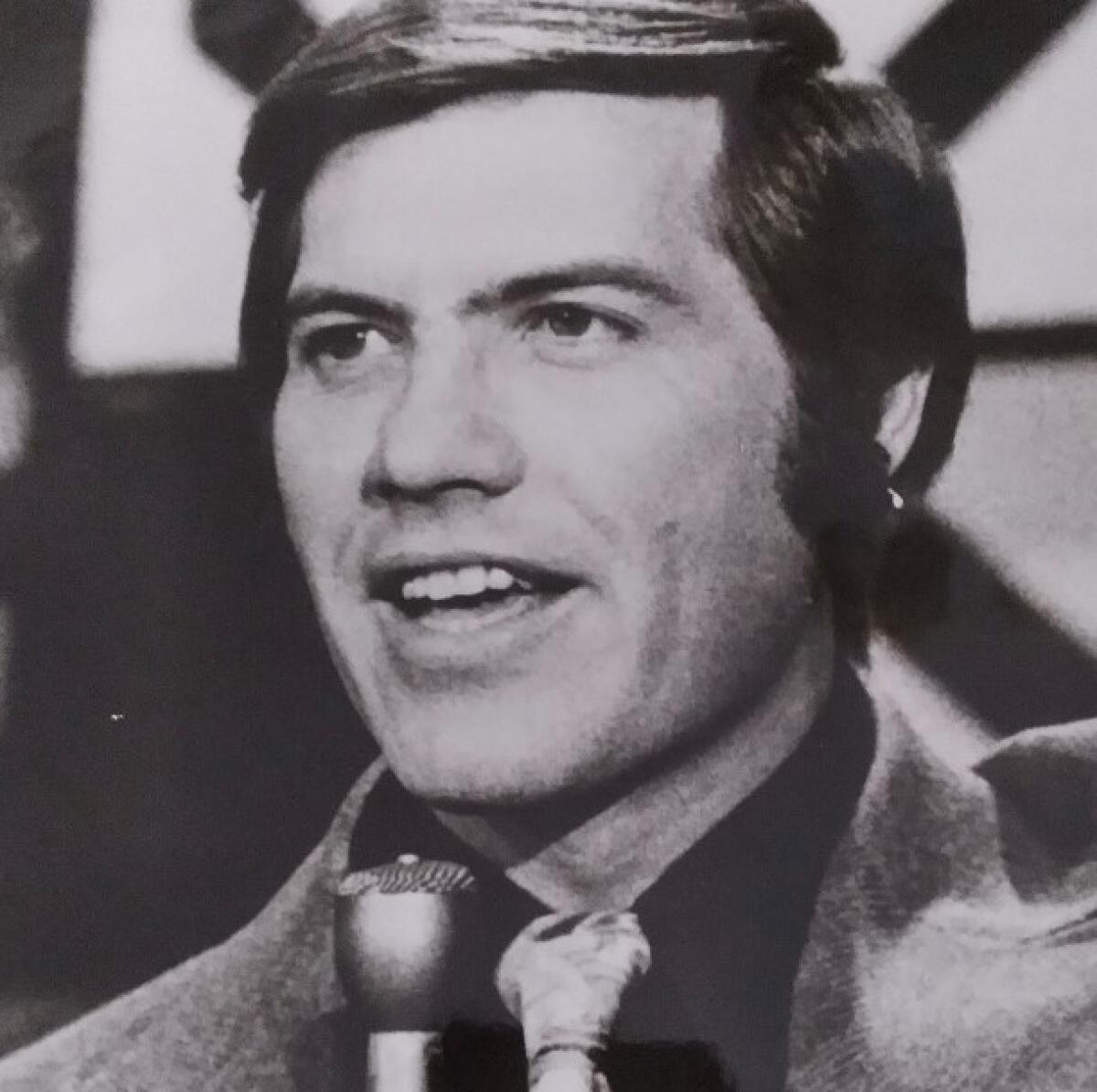

Sam Riddle, who died Sept. 27 at 83, was a Los Angeles disc jockey and the host, in the mid-1960s, of the daily television record hop “9th Street West” (the 9 was for Channel 9, where KHJ, now KCAL, resided on the VHF dial) and of the weekly prime-time “Hollywood a Go Go,” a performance show like ABC’s “Shindig!” and NBC’s “Hullabaloo.” (There were performances on “9th Street West” as well, and an audience of dancing kids on both.)

The two shows ran simultaneously. “Hollywood a Go Go” logged 58 episodes, plus an “Aloha a Go Go” special shot in Hawaii, from the end of 1964 to the beginning of 1966. Much of it is available to see online (and is minutely documented on a website dedicated to the Gazzarri Dancers, who brought Sunset Strip energy into the studio). “9th Street West” went out live and appears to have entirely disappeared into the ether, though rooting through the rummage of the internet, I did find that the Doors and the Supremes both made appearances. “9th St. West” carried on longer, becoming “Boss City,” in which Riddle was paired with Kam Nelson, who had a special way of dancing many Angelenos will recall, and “The Groovy Show,” which eventually morphed into “The Real Don Steele Show.” It is a little hard to piece it together; the record can be vague and sometimes contradictory.

The set was designed to suggest the close quarters of a discotheque. On the cusp of the swinging ’60s evolving into something more psychedelic, there was a suit-and-tie rule for the men. (This was still standard for many pop acts as well.) One can’t help but note the thoroughgoing whiteness of the dancing audience, but the bookings, like the charts, were more diverse: Alongside the Byrds, the Rolling Stones, the Lovin’ Spoonful, the Turtles and Sonny & Cher — and bands no one who has not made a deep study of the period will have ever heard of — there were appearances by Black artists including James Brown, Aretha Franklin, Bo Diddley, Tina Turner, Chuck Berry, Fontella Bass, Marvin Gaye, the Four Tops, the Olympics, Wilson Pickett and many more. The show was syndicated globally and banned in Ireland.

KHJ-93 DJ Sam Riddle helped bring Sonny & Cher and the Monkees to fame.

Riddle, who was one of the KHJ (radio) “Boss Jocks,” was smooth, good-looking in a clean-cut way but not conservative in manner, like a junior executive with a hipper cut to his jackets; he might have plausibly played the boyfriend on a ’60s sitcom. (His own TV shows called upon him to act a little, and he could act, a little.) But he was more of a piece with the kids than was, say, Dick Clark, like a high school English teacher out of college. Riddle might dance a little (he could dance, a little), or lip-sync to his own performance of “Long Tall Texan,” or lead the cast in a rendition of “Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious.” He issued at least one single, “Angela Jones” backed with “Lollipops & Teardrops.” (You can pick it up on EBay as of this writing, for $10 plus shipping.) It’s quite all right. He could sing a little, too. He was a little corny, at times — or the scripts were — but the enthusiasm was real enough.

Disc jockeys meant a lot then. Their names were sung in jingles, and though there may be disc jockeys in the world now who have some similar authority, I doubt many of them have their names sung in jingles. If you were young enough then, and were barely informed about the adult world, they seemed to know something mysterious and important. Theirs might be the last voice you heard before you fell asleep, radio tucked under your pillow. But Riddle was more than a voice, he was a familiar face, he was on television. And then he wasn’t. (Like Kirk, he became invisible. Like Clark, he went into production — “Star Search,” “The Ultimate Poker Challenge” and some other things.) But he left a mark on his decade, and his city, and people who were there, listening, watching.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.