The true story of the women who made ‘The Daily Show’ — and were ‘erased’ from its legacy

- Share via

At least in the public imagination, Jon Stewart is the person most responsible for “The Daily Show’s” improbable rise. He’s the visionary host who transformed the late-night show, once considered Comedy Central’s answer to “SportsCenter,” into a powerful force in American politics, a launchpad for a new generation of comedy talent and, for many, a trusted source of information.

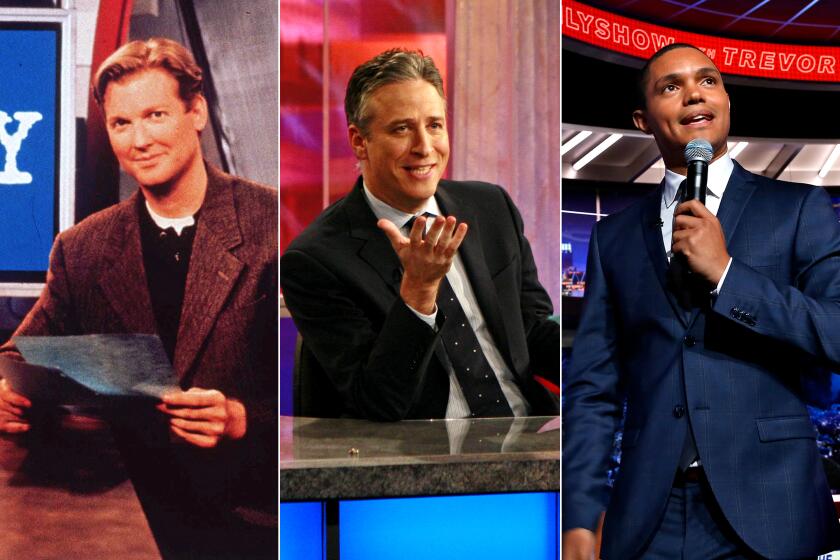

But the Great Man Theory of “The Daily Show,” which also includes Stewart’s predecessor and inaugural host, Craig Kilborn, and successor and current host, Trevor Noah, overlooks the contributions of two women essential to the series’ success: its creators.

The story of one of the most influential programs of the last 25 years can be traced back to the day, circa 1994, when TV producer Madeleine Smithberg and comedian Lizz Winstead moved into the same building on West 20th Street in Manhattan, a brownstone where Jack Kerouac had written some of “On the Road.” When given the opportunity to develop a late-night show on a shoestring budget for what was then a cable backwater, the neighbors-turned-friends created an enduring and surprisingly adaptable new form of satire that remains ubiquitous in late-night TV.

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

And they’d be happy if their contributions were more widely acknowledged.

“It’s astounding how many people don’t know that two women created ‘The Daily Show,’” says Winstead, who gathered with Smithberg and several original correspondents for a virtual reunion this week. “Madeleine and I did a lot of work to lay out this cool show. It exists for a reason — because we worked for hardly any money to make it happen.”

Doug Herzog, who commissioned the show while president of Comedy Central, agrees: “They put this thing on the air, they brought it to life, they nurtured it. There’s obviously no ‘Daily Show’ without Madeleine and Lizz,” he says. “This was a show led by two women at a time when late night was a boys’ club.”

Times television critics Lorraine Ali and Robert Lloyd discuss the profound influence of “The Daily Show” in its 25 years on air.

Back when they became neighbors in 1994, Smithberg was producing“The Jon Stewart Show,” a quirky late-night show that had started on MTV before moving into syndication. At the time, Stewart was a sharp young comedian best known for losing the “Late Night” hosting gig to Conan O’Brien.

Smithberg recruited Winstead, a stand-up comedian who specialized in politically charged material, to work for her as a segment producer. “The Jon Stewart Show” was soon canceled, going down in actual flames when Marilyn Manson started a fire onstage.

But Smithberg and Winstead were on to their next idea: a scripted series, inspired by “The Larry Sanders Show,” set behind the scenes of a fictional cable network.

They pitched the idea to Herzog. At the time, Comedy Central was “a network in search of an identity and an audience,” he says. It had a few original productions, including the panel show “Politically Incorrect” and the animated series “Dr. Katz, Professional Therapist,” but other than that it was mostly “Absolutely Fabulous” reruns and old Gallagher specials. When Bill Maher unceremoniously decided to take “Politically Incorrect” to ABC, Herzog had a void to fill.

Herzog thought the “Larry Sanders”-style show Smithberg and Winstead were developing would be too expensive to make. Instead, he urged them to focus on what he’d started referring to as “The Daily Show” — a nightly broadcast that would function as the network’s home base. His fuzzy idea was for something “part ‘SportsCenter,’ part Howard Stern, part ‘Weekend Update’” featuring someone at a desk, he says.

When Herzog guaranteed Smithberg and Winstead a year on the air, with no pilot necessary, they could no longer refuse.

“Just knowing that you’re not going to be canceled tomorrow, which I’ve had on almost every other show I’ve ever worked on, takes that weight off of a creative team,” says Smithberg, who had spent six years as a talent producer at “Late Night With David Letterman” before branching out on her own.

With ‘The Daily Show’ turning 25, we look back on major turning points in the series’ first quarter century, as covered by The Times.

Resisting pressure to focus on pop-culture headlines, she and Winstead came up with the idea to turn “The Daily Show” into a parody of the news.

At the time, the hyper-partisan media landscape we now take for granted was still years away — Fox News and MSNBC launched in 1996, the same year as “The Daily Show” — and newsmagazines were in the ascendance. The major broadcast networks had discovered they could pad their lineup with inexpensive shows like “48 Hours,” “20/20” and especially “Dateline NBC,” which aired as many as four times a week in the mid-1990s.

The tone of these shows — and the local news broadcasts that still garnered big audiences — was relentlessly alarmist, Winstead recalls: “Every piece was like, ‘Your mattress: What you don’t know might kill you!’”

She had enlisted her then-boyfriend, Brian Unger, early in the development process. A former producer for CBS News who had grown disillusioned with broadcast journalism, Unger would vent about the business. They studied “Dateline’s” anchor, Stone Phillips, taking note of his earnest listening face and other self-important mannerisms.

In the middle of one of those sessions came “the aha moment of all aha moments,” Smithberg remembers. “We all kind of looked at each other and said, ‘Oh, my God, we can pretend that we’re them. And if we pretend we’re them, we can make fun of them while we’re also delivering the news!’”

“I often say that Stone Phillips deserves a ‘created by’ credit with me and Lizz, as does Brian Unger,” she adds.

For the joke to really land, “The Daily Show” had to look just right. The goal, according to Winstead, was that “if you turned the volume down, you would have no idea it was a satire.” Unger taught the other correspondents, including former “Saturday Night Live” writer A. Whitney Brown, to light and shoot their segments.

I think that the first 2 ½ years of the show, where the bones were being built, have been systematically and intentionally erased from public record.

— ‘The Daily Show’ co-creator Madeleine Smithberg

In this regard Kilborn, a “SportsCenter” anchor, was perfect for the job: tall, blond, looked good in a suit, understood the cadence of TV news. He didn’t have a very strong political point of view — his trademark bit was the cheeky “Five Questions” — but Smithberg, as showrunner, and Winstead, as head writer, didn’t necessarily need that.

“He was like Ted Baxter,” says Smithberg, comparing him to the newsman played by Ted Knight on “The Mary Tyler Moore Show.” “It was like our writers had a ventriloquist’s dummy. They could put any words into his mouth.”

The show’s slogan was “When news breaks, we fix it,” and from Day One it offered sharp commentary designed for a media-savvy audience.

A recurring segment called “Trial of the Century of the Week” skewered the very ’90s obsession with high-profile criminal cases. Beth Littleford did Barbara Walters-style celebrity interviews with a literal soft focus: The lens was so blurry you could hardly make out her features.

Winstead and Smithberg looked for correspondents with improv training because they were nimble enough to do the deadpan interviews that instantly became a “Daily Show” hallmark. (In the show’s very first field piece, Unger interviewed a woman obsessed with her dead cat.)

Stephen Colbert joined the show in 1997 and elevated the correspondent shtick to an art form, Smithberg says: “We saw what comedy genius was up close.”

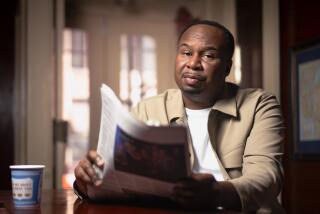

‘Daily Show’ correspondents Ronny Chieng, Michael Kosta, Desi Lydic, Dulcé Sloan and Roy Wood Jr. take us behind the scenes of the ‘comedy PhD program.’

“The Daily Show” was not a massive hit, but it caught on with younger male viewers — even more so once “South Park” premiered on Comedy Central in 1997 — and, of course, the self-obsessed news media.

“It was like this thing that was missing from our lives that we never knew was missing,” says Winstead, who also appeared as a correspondent.

Kilborn quickly became a star, but the attention also led to trouble. A story published in Esquire in January 1998 detailed the behind-the-scenes tensions between Kilborn and the show’s female creators. After several rounds of Scotch, Kilborn referred to some of the women on staff as “bitches” and said that Winstead would perform oral sex on him if he wanted. He later issued a public apology and was suspended for a week.

Soon after, Winstead walked away from the show she had created. Even now, she declines to elaborate about the decision. “I hardly ever talk about it,” she says. “This show was my passion for a reason. And every single thing that I’ve done since has been a reflection of that.”

By year’s end, Kilborn was gone too, heading to CBS to take over for Tom Snyder at “The Late Late Show” — a job many had thought would go to Stewart. In a statement to The Times, Kilborn said he remains grateful for his time on “The Daily Show” because it helped him land his dream job but believes that creatively “there were major disconnects” because he was hired after the concept was already in place. (“Don’t drink and interview,” he adds.)

Smithberg stayed on as showrunner, convincing her old friend Stewart to step behind the “Daily Show” desk. (Herzog says he tried unsuccessfully to get Jimmy Kimmel to take the job.)

Smithberg steered the show through the extended chaos of the 2000 election — “the moment where the show became ‘The Daily Show With Jon Stewart’ that everybody knew and loved,” she says — and eventually left the show in 2003, just as the war in Iraq was ramping up.

“The Daily Show” won the Emmy for variety series for the first time that September, but Smithberg was not onstage to receive the award.

For the series’ 25th anniversary, we look back on a few of its most memorable guests, with insights from ‘The Daily Show’ bookers and showrunner.

“He bought a house and renovated it,” Smithberg says of Stewart’s role in transforming “The Daily Show,” “but he didn’t build the house.” (Stewart did not respond to The Times’ request for comment on this story.)

Over the next 12 years, millions of fans would look to Stewart as a voice of reason in an increasingly skewed media landscape. “The Daily Show” became a legitimate platform for politicians, authors and even sitting presidents to reach the public. NBC even considered offering Stewart a job anchoring “Meet the Press.” When Stewart announced in February 2015 that he would be stepping down later that year, it overshadowed the news that an actual anchor, NBC’s Brian Williams, had been suspended from his job the same day.

Though widely revered, Stewart also faced occasional criticism for enabling a boys’ club atmosphere at “The Daily Show.” For much of his tenure, the show had no female writers, a fact that became glaringly apparent every year at the Emmys.

Though she and Winstead have been minimized in the narrative of the series’ legacy, Smithberg still sees their creative imprint on “The Daily Show,” from the “moment of Zen” — inspired by her cat’s love of Charles Kuralt — to the intro she wrote for longtime contributor Lewis Black. But she wishes their work were recognized alongside that of the series’ male hosts.

“I think that the first 2½ years of the show, where the bones were being built, have been systematically and intentionally erased from public record,” she says. (You can still watch 20-year-old episodes of “The Daily Show With Jon Stewart” on the Comedy Central website, but clips from the Kilborn era are not available online except through a few dubious YouTube accounts.)

Smithberg now lives outside Seattle and recently started a cooking show on YouTube called “Mad in the Kitchen.”

Winstead, who went on to co-found Air America, the liberal talk radio network that helped launch Rachel Maddow’s career, and Abortion Access Front, a reproductive rights organization, still watches “The Daily Show.” And she’s surprised whenever people are surprised by this.

“I’m so excited it didn’t fizzle out,” she says. “I love seeing my instincts pay off.”

The sheer longevity of “The Daily Show” — and the many shows it inspired — proves “you can be factually accurate, funny, and punch up,” she says. And Winstead doesn’t buy the idea, put forward by many, that “The Daily Show” sowed distrust in the media.

“Don’t say, ‘Oh, “The Daily Show” is creating cynics.’ No, the news media created the cynics,” she says, “and those cynics created ‘The Daily Show.’”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.