How Johnny Canales, the Mexican American Dick Clark, helped make Selena a star

- Share via

In the third episode of Netflix’s “Selena: The Series,” the burgeoning star and her family band are booked by television variety host Johnny Canales (Luis Bordonada) to play in the Mexican border town of Matamoros. It’s a pivotal sequence, one that not only highlights the first time Selena y Los Dinos performed in Mexico, but the moment they successfully crossed over into the Mexican market.

It is one of Selena’s many big breaks.

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

That April 26, 1986, taping of “The Johnny Canales Show” was also a historic television moment: It was the first time an American production had recorded in Mexico with a live audience. And as with Selena, it proved a watershed moment for Canales, a sign of successes to come.

For younger and/or non-Latino viewers, “Selena: The Series,” which premieres Friday, will be their introduction to the host, who is credited with helping launch the U.S. careers of many Spanish-singing musicians, Selena Quintanilla-Pérez being the most notable example.

For older audiences, it will be a chance to reacquaint themselves with the man responsible for spreading the gospel of Tejano, conjunto, norteño and other Mexican and Texan regional genres internationally.

“Johnny Canales is the Mexican American equivalent of Dick Clark because he broke everyone in,” said Ramón Hernández, a writer, photographer, historian and musicologist considered to be one of the foremost experts on Tejano. He also served, without pay, as Selena’s first photographer and publicist.

It was Hernández who booked her first appearance on “The Johnny Canales Show” in 1985 — an episode that, much like the one the following year in Matamoros, has become part of Selena’s lore. It was during that first appearance that Canales gently ribbed Selena by telling her she needed to work on her Spanish.

“You didn’t have to be famous, you didn’t have to have a top selling record,” Hernández said. “He would just put you on.”

‘Please don’t think I think I’m her,’ Christian Serratos says of her headlining role in the Netflix series about Tejano icon Selena. ‘I know I’m not her.’

Canales’ relationship with music began at an early age. Born in the tiny Mexican town of General Treviño in 1947, he was raised in Robstown, Texas, where as a child he tagged along with his father and performed at local bars for change.

It was a fitting place to grow up: Robstown gave Texas hold’em poker to the world, and Canales has spent much of his life betting on himself.

After a brief stint in the Army, he formed Johnny Canales y su Orchestra. In 1977, he became a disc jockey at a Corpus Christi radio station. Within a year, a local Coors distributor tapped him to host a Tejano and conjunto music variety show.

That was the genesis of “The Johnny Canales Show.”

Canales’ program was a big hit. By the mid-1980s, “The Johnny Canales Show” was one of the most syndicated programs in the United States despite being mostly in Spanish. It was also broadcast in Mexico, where the show was sponsored by department store Soriana.

Dr. Norma E. Cantú, humanities professor at Trinity University in San Antonio and an expert on Texas borderland culture, chalks up Canales’ success to his ability to tap into the Tex-Mex zeitgeist, bookings acts like Little Joe y La Familia and the Texas Tornados, a band that fused rock, conjunto and country, and whose members included Freddy Fender, Flaco Jiménez, Doug Sahm and Augie Meyers — Texas music royalty.

Canales didn’t book just musical acts. Latino luminaries like politician Henry Cisneros, comedian Cheech Marin and even Mario Moreno — better known as Cantinflas, Mexico’s answer to Charlie Chaplin — were among his many interviewees.

“You didn’t see that anywhere else in the media,” Cantú said, “so one of the legacies of the show is that it was a place where we could finally see ourselves.”

Canales capitalized on the so-called “Decade of the Hispanic” — a term coined in the early 1980s to acknowledge the large swath of bicultural people who inhabited what became the United States and shaped its history and culture long before it was even formed. In 1980, there were an estimated 14.6 million Latinos in the U.S. A decade later, that figure had grown to 22.4 million.

“Selena: The Series” turns the focus to the men behind her — creating a self-serving, controlled narrative that fails to illuminate the late singer herself.

Cantú, who grew up in Laredo, also points to Canales’ gift of Spanglish gab as a reason for his mass appeal.

“The language that he used was familiar. It was how we spoke,” she said.

A perfect example of Canales’ linguistic mannerisms can be found in a 1988 Texas Monthly profile, in which he jokingly claims that the first part of his ubiquitous catchphrase “You got it, take it away!” was actually an attempt to help his Mexican viewers.

“Well, Mexican people, first thing they want to do is learn a little English, and I help them a lot because I use the term ‘You got it,’” he explained. “When they go down there to cross the border and the immigration says, ‘Are you an American citizen?’ they say, ‘You got it,’ and the immigration says, ‘OK, go ahead.’” (Canales declined multiple interview requests for this story.)

In 1988, the already popular variety show exploded after it was picked up by Univision, giving Canales international distribution. By that point, he had expanded the types of acts he booked. Household names like Bronco, Los Tigres del Norte, La Sonora Dinamita and La Mafia graced television screens from places as far as Fairbanks, Alaska, to Managua, Nicaragua. “The Johnny Canales Show” became part of the Sunday morning ritual for millions of households across Latin America.

As his show grew, Canales always made it a point to center his fans.

“One of the things I really liked about his show was how he would give shout-outs to different Latin American countries and regions,” said Eduardo Martinez, a barrio historian from the Rio Grande Valley and former newspaper columnist.

Canales was of and for the people — not unlike Selena, who made several appearances on the program as her own star rose. During these visits, Canales’ demeanor was akin to a proud uncle, more than happy to boast about the accomplishments of someone he considered one of his own.

In a 1994 episode, Selena’s last appearance on the show before she was murdered the following year, the television host kept calling her the queen of Corpus Christi, the queen of the Spanish-speaking world.

“We wish you the best that life has to offer,” he gushed in Spanish, “and don’t forget us, which you’ve never done.”

“Claro que no! I’ll always remember you,” Selena replied.

Producer Jaime Dávila wants the industry to know this about Latinos: “We’re not a separate category. We’re part of America. We’re part of the mainstream.”

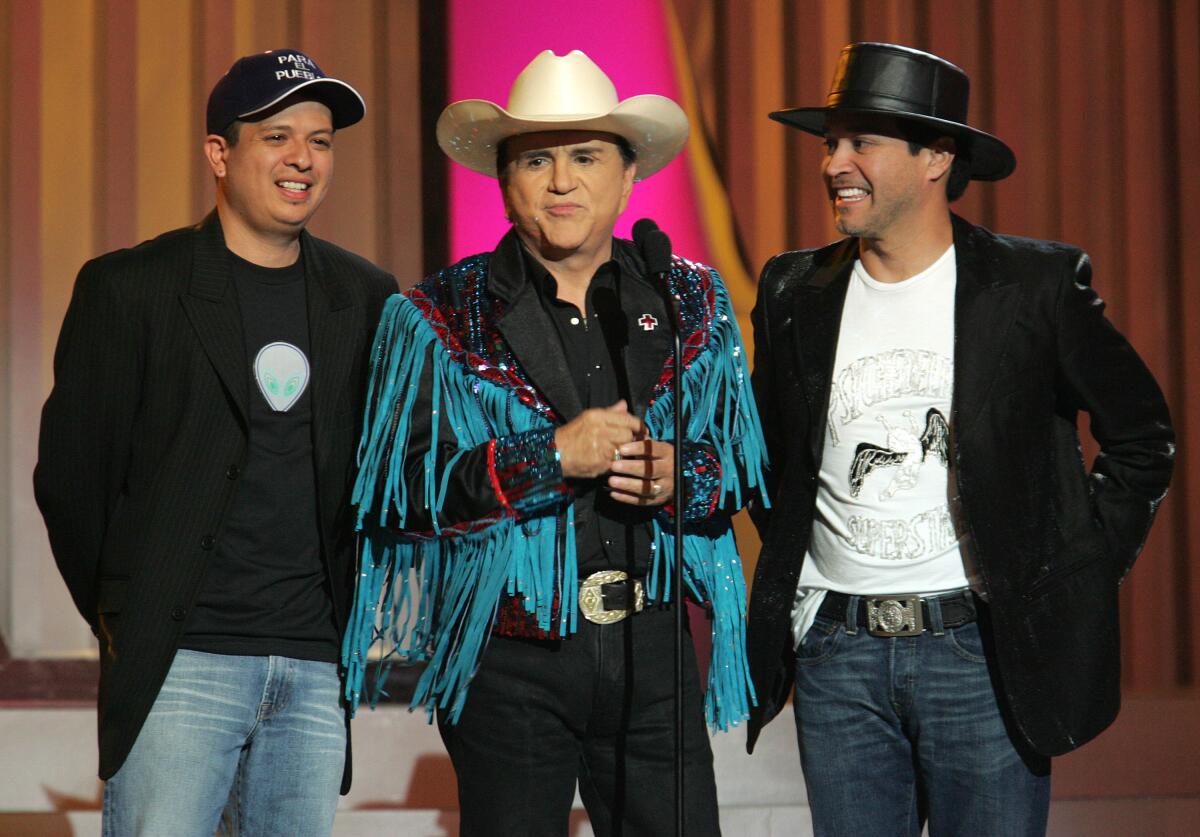

Norteño music stars Ramon Ayala and Eliseo Robles reunite on “El Nuevo Show de Johnny y Nora Canales” in 2017.

Canales’ relationship with Univision soured after the network was bought by a group that included Mexican television giant Televisa in 1992, and in 1996 he took his show to rival Telemundo — where it thrived, despite Telemundo’s lower Latino market share. The host’s audience followed, and he remained a tastemaker.

“He’s pivotal. One of our primary focuses of our promotion of artists is to get them on the show,” an EMI Latin executive told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram in a 1998 story about Canales. “It creates interest, and we can use the applause level at the show as a gauging system to see if a song should be released as a single.”

The turn of the new millennium marked the decline of “The Johnny Canales Show”: With the rise of the internet, the need for a weekly variety show to introduce audiences to up-and-coming bands declined. In 2005, Telemundo canceled the program. Canales faded from the spotlight because of health concerns, undergoing five bypass surgeries in the years that followed.

“I think the world changed in a lot of ways, and he represented a particular time and place in music,” Martinez said. “We tend to always think of him as being from that time and place.”

In 2013, Canales rebooted his show, added a co-host — his wife — and redubbed it “El Nuevo Show de Johnny y Nora Canales.” The program lasted a few years, albeit at a much smaller scale. Canales was no longer recording in an auditorium, instead taping his shows in the back of a musical instrument store in McAllen, Texas.

Despite his diminished profile, Canales still had the ability to draw big acts. In 2017, his show reunited Ramon Ayala, el rey del acordeón, with his estranged former singer, Eliseo Robles. In the world of norteño music, this was like bringing the Beatles back together.

Canales never really went away, the internet, which contributed to his show’s demise, also keeping his legacy alive. YouTube is rife with clips from his old show. That aforementioned Ayala/Robles performance is available on the platform, where it has amassed more than 10 million views since it was posted.

Don’t be surprised if those uploads gain even more viewers because of “Selena: The Series.” As long as they live on somewhere, Johnny Canales, and his show, have still got it.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.