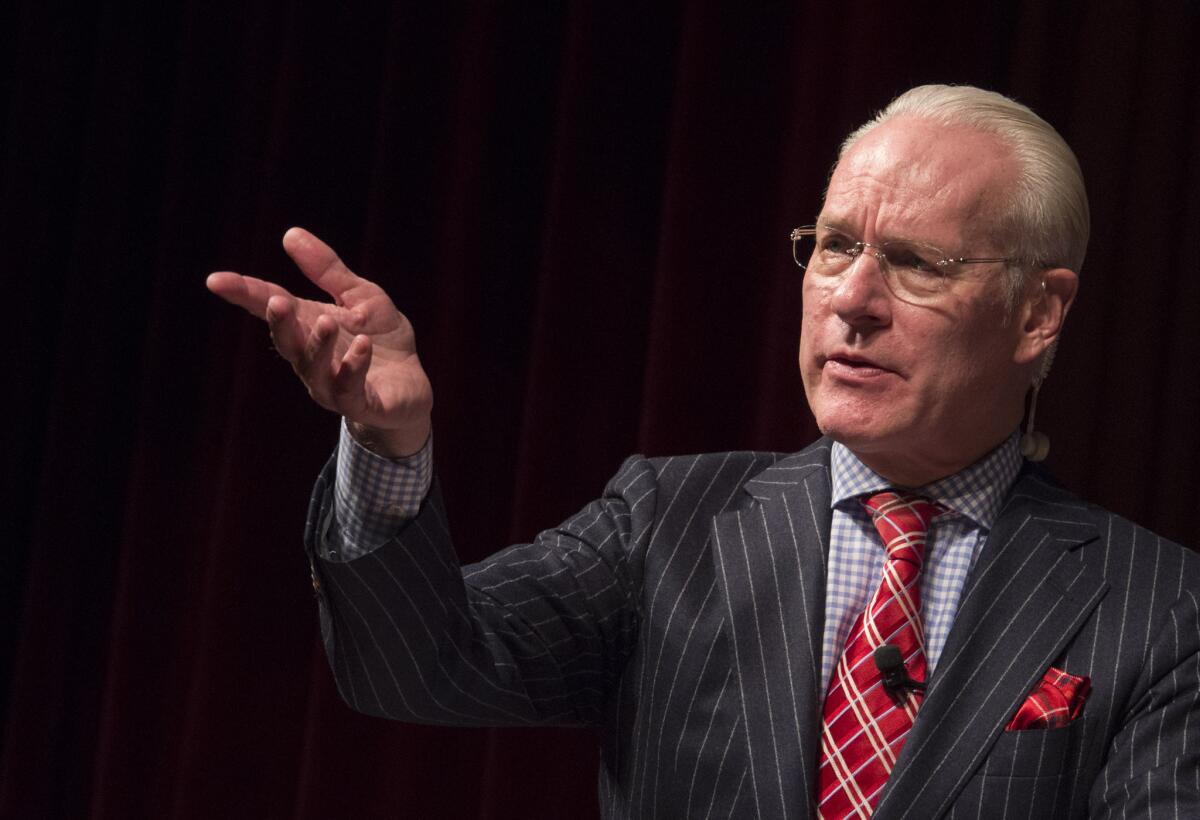

TV mentor Tim Gunn is freaked out too: ‘Every night at 7 o’clock I burst into tears’

- Share via

“How’s Los Angeles holding up with this horrible virus?”

Fashion guru Tim Gunn is concerned about us — you, me, L.A., New York, everyone. And having made his name as TV’s most effective mentor on the reality-competition series “Project Runway,” it’s no surprise he lobs the question before I do. After all, the former chair of fashion at New York’s Parsons School of Design prefers “the Socratic method” to what those in education call the “sage on the stage” approach.

“I never assert my own design aesthetic on the designers because it would be self-defeating,” Gunn tells The Times in a phone interview from his home in Manhattan. “I’m not who they are. I’m not the person they’re clothing.”

Gunn’s encouraging, unfailingly honest guidance of up-and-coming design talent helped turn “Runway” into a sensation when it debuted in 2004, and also inspired his most recent book, “The Natty Professor: A Master Class on Mentoring, Motivating, and Making It Work!” Now, with supermodel co-host Heidi Klum and longtime “Project Runway” showrunner Sara Rea at his side, Gunn’s trusty advice has a new outlet: Amazon’s globe-trotting, ultra-luxe design competition “Making the Cut,” which is to its forerunner what a Michelin-star restaurant is to your favorite neighborhood haunt.

While “Making the Cut” features a number of twists on the “Project Runway” template — an international cast; more established designers; Naomi Campbell as the sharpest-tongued reality TV judge this side of Simon Cowell — Gunn remains an irrepressible (if often tearful) advocate for his charges. He’s even willing to throw the tiniest modicum of shade at the boldfaced names he’s encountered in the guest judge’s chair over the years, even if he’s not naming them.

“There are so few times when a fashion designer can really just leave their own aesthetic at the door,” Gunn says. “It wasn’t your assignment! It’s not your work! None of that is even remotely helpful. But that happens a lot.”

I spoke with Gunn about how much New York during the coronavirus outbreak feels like New York after Sept. 11, the “a-ha” moment that changed his approach to teaching forever, and why he, Klum and Rea aren’t content just to “tweak” “Making the Cut” if it’s renewed for a second season. The interview has been edited for clarity and condensed.

Where are you right now? What are you doing to stay healthy and sane at this moment?

Well, I’m staying healthy — I don’t know how sane I’m staying. I’m on the Upper West Side of New York, and it’s just freaky. I have a view of Amsterdam Avenue for about a mile and a half. No cars. No people. The only thing you can see are emergency vehicles with the sirens going. It’s apocalyptic.

The noise of the sirens is what keeps being mentioned as the thing that is most striking.

It is. And they say that the emergency vehicles have never had this much activity since Sept. 11. Which is understandable. The city feels very much the same [as it did then].

In addition to the frightening aspect, do you feel similar about the solidarity aspect — New Yorkers banding together?

There are not as many opportunities to show solidarity, since we’re not allowed out. But I will tell you, at 7 p.m. every evening, there is a minute of clapping. People are throwing open their windows. They’re stepping out on their balcony. They’re banging pots and pans. It’s to celebrate the emergency rescue workers and hospital staff. And every night at 7 o’clock I burst into tears.

Heidi and I were so concerned about “Making the Cut” premiering at this time, thinking, “Oh, God, this doesn’t seem appropriate.” But then we thought, “You know? The world needs a pick-me-up. We need something that lifts our spirits. We need something that’s inspiring and that’s also a distraction.”

I have been especially taken with the gorgeous locations you have been to thus far. Being trapped at home, there’s something very seductive about it — and maybe a little bit bittersweet.

How spectacular is the footage? It’s cinematic. It’s otherworldly. After watching the premiere, I wanted to talk to you about your mentoring style. Was there an “a-ha” moment for you as a teacher in terms of what worked and what didn’t about mentoring up-and-coming designers?

I’ve had a lot of “a-ha” moments. One was early on in teaching, I would say within the first year. I approached my teaching responsibilities as though I was the answer man, and I had to know all. I would make myself into a wreck just anticipating what students may ask: “Do I know how to answer that?” But I thought: “This is ridiculous. ... I need to put this back on the students.”

So someone would ask a question and I would say: “Great question. For our next class, I want all of you to research this question, and I want you to find an answer or a point of departure for discussion that you think no one else will have found.” It was so liberating! First of all, the students were much more engaged in what the issues were, and it took this huge weight off of my shoulders.

Is there a trick to boiling down your advice to the designers that makes for compelling television?

Oh, Matt! Want to hear the truth? I’m with each designer for 10 to 15 minutes, easily. So, in the edit, they boil it down to a few sound bites. Because it looks as though I’m in and out of that room in an hour. And in fact, on “Project Runway,” when we would have 16 designers, that critique session would be four hours long.

It’s not that I’m long-winded — I have a very Socratic approach to this. I pummel people with questions, because I can’t begin to respond to their work until I know what’s going on. What are their goals? What was their point of departure? How do they feel about the work?

From slapstick comedy to snooty stoicism, British television is a soothing escape from troubled times. Plus all those great accents.

I try to ask enough questions to get them to see what I see, whether that’s something good, bad or indifferent. Frankly, on “Making the Cut” we’re not talking about janky hems the way we did on “Runway.” It’s to get the designer to say, “Oh, this asymmetrical look is not what I’m going for.”

Occasionally on “Making the Cut” I’ll do this, but I did it a lot on “Runway.” Because of the camera placement, I would say, “I want you to come over here and look at it from my point of view. You’re standing 18 inches from it and I’m standing six feet from it. So come over here and look at it. Now tell me what you see.”

I see it as a kind of spiritual partnership. But it’s also about waking the individual up — helping them realize that they already have the tools to do this analysis.

Do you have a philosophy around the balance of positive and critical feedback that you offer designers? You want to be honest, but you don’t want people to feel beaten down, either.

This is true with my students, it was certainly true on “Runway,” and it’s true of “Making the Cut”: The longer you have the relationship with the individual, the more you know them and they know you. For instance, I’m reminded of Season 13 of “Project Runway,” when I think I was the bluntest instrument I’ve ever been. I went to Alexander Knox and just said to him: “This is the most hideous garment I’ve ever seen in my entire life. What happened to you? You were so talented! You were so capable! You’re still here! What happened?” Because I can’t mince words. And he knows I have great appreciation and respect for his work. I needed to wake him up, because it was just horrendous.

It’s never intended to be mean-spirited. It’s only meant to help. I just want the designers to achieve the highest level of work that they can under the circumstances. ... But I try to mix it up. I found early on teaching that if you’re just critical, the students discredit what you’re saying. They shut you out. It’s as though they’ve pulled down a garage door.

Do you think your approach to mentoring has changed with the more accomplished contestants on ‘Making the Cut’ versus the average ‘Runway’ contestant?

Yes. And there’s another factor that’s critically important to all of this. With “Making the Cut,” we’re looking for the next big fashion brand, so my conversations with the designers are largely about, “How do these designs” — and there are always at least two for every assignment — “fit into the larger vision of your brand?” As opposed to looking at the minutia of the stitching or how the sleeve is set into the bodice. It’s a much broader dialogue, and I find it much more interesting.

And the judging format on ‘Making the Cut’ repurposes the Socratic method you’re talking about in a way that goes beyond ‘Runway.’

The frequency with which I agreed with the judging on “Runway” was ... infrequent. I frequently disagreed. And on “Making the Cut,” I never once disagreed, and it’s because of the depth of the discussion with the designers — the depth and the breadth. It makes a huge difference to the outcome. It means that the outcome is much more rational. It’s less intuitive. ... It’s really fair. I wasn’t expecting that. I thought, “Oh, God, here we go again, I’m going to be getting mad every time we have a judging panel.”

If you do another season of ‘Making the Cut,’ is there anything you would tweak to improve it?

Sara [Rea] and I speak several times a week, and we’ve already said to each other — and Heidi — that we can’t get stuck in this format. That was the problem with “Runway’s” success. No one would let us budge from the format.

We need to establish now that if we do in fact do a Season 2, we need to change things up. And if there’s a [Season] 3, change it up again. It’s not so much that we’re thinking about tweaking as we’re thinking about big change. Whether there is a Season 2 remains to be seen ... but we’re intent on not getting stuck. What inspired me to reach out for this interview is the moment in ‘Making the Cut’s’ second episode in which contestant Martha Gottwald has a bit of a crisis. You’re tasked with talking her out of leaving the show. Would you mentor me and our readers a moment and give them a piece of advice for how to bear up when things are hard?

For one, and I know this from my own life crises, we’re not a solo act. We need people around us who can help us, whoever that may be — a family member, a friend, a teacher, a coach. And we need to be honest with ourselves about what we’re going through.

Is there anything you think I missed, or want to add?

I have one little anecdote I’d like to tell you about Season 1, episode one of “Runway,” when I was transitioning from teaching to being a mentor.

I am in the sewing room threading a bobbin, and one of the executive producers came into the sewing room, knocked — because the cameras are rolling — [and says], “Tim, can I speak to you for a minute out in the hallway?” So I went out into the hallway and she asked me, “What are you doing?”

“What am I doing? I’m threading the bobbin.”

“But why?”

“Well, Designer X is having trouble with it.”

“I want you to know something. If you’re threading the bobbin for her, then you have to thread the bobbin for all the other designers in each and every episode.”

“What? I’m getting out of there!”

It’s a fairness issue. You need to keep some distance.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.