How did ‘Homeland’ survive this long? By doing what TV does best: evolve

- Share via

Yes, “Homeland” is still on.

In conversation and on social media, the longevity of Showtime’s counterterrorism drama, which begins its eighth and final season Sunday, often comes as a surprise. After all, it’s been more than eight years since its gripping first season — which premiered almost exactly one decade after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001 — dominated the cultural conversation, and its favor with Emmy voters and viewers alike peaked shortly thereafter. But there’s a reason the series, created by “24” veterans Howard Gordon and Alex Gansa from Gideon Raff’s Israeli “Prisoners of War,” has survived a sea change — or several — in both the medium of television and the so-called war on terror.

“Homeland” is the most adaptable show on television.

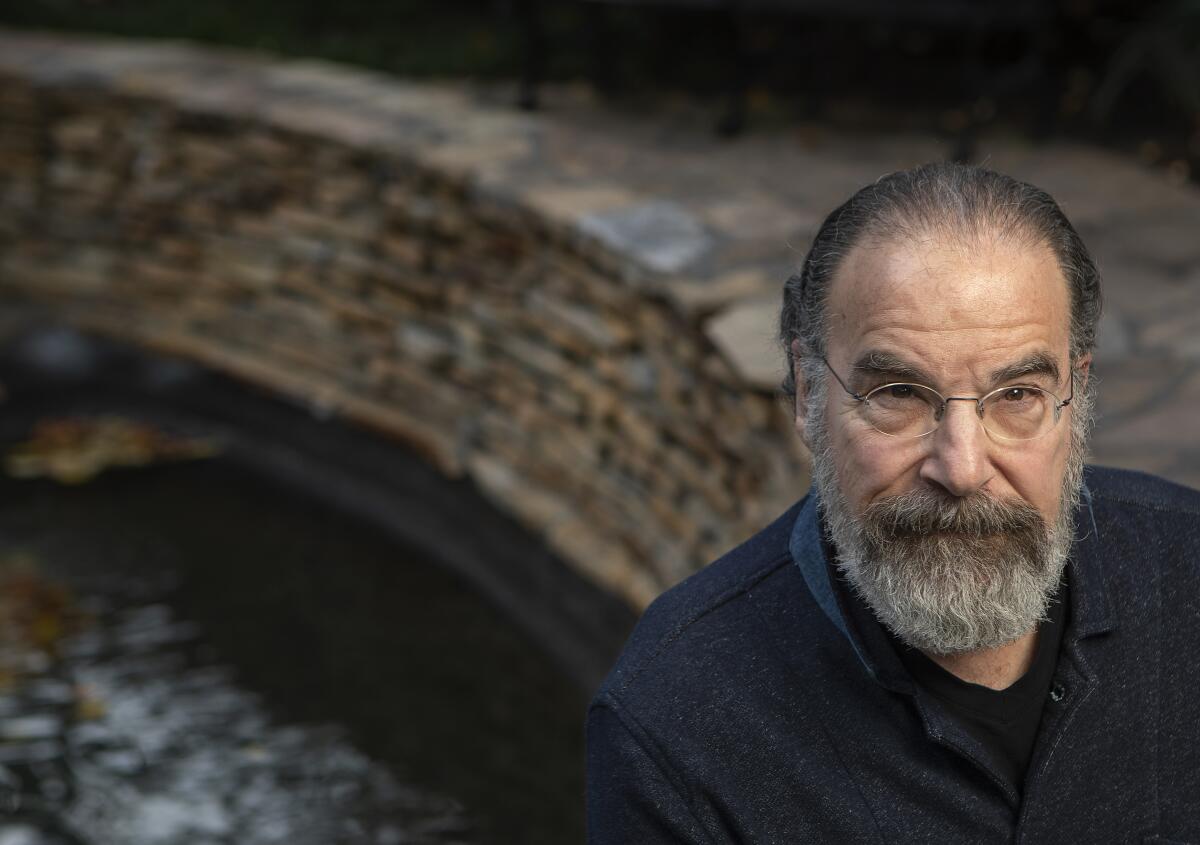

Conceived as the dual portrait of a mentor — Mandy Patinkin’s Saul Berenson — shepherding his protégé — Claire Danes’ Carrie Mathison — through the thornbush of the Central Intelligence Agency, the series has since been a cat-and-mouse game, a fraught romance, a stripped-down spy thriller and a domestic political drama; a critics’ darling, a disappointment, a comeback kid. It embodies, perhaps more than any series to emerge from the medium’s recent “Golden Age,” the feature that differentiates TV from most other art forms: evolution over time.

“The image that comes to mind is origami,” Danes says. “You can keep refolding the paper, and it can take a different shape.”

‘Insane enthusiasm’

Even at the outset, the shape of “Homeland” was far from certain. The first series under both Showtime chief David Nevins and Fox 21 head Bert Salke, “Homeland” attracted an “onerous” amount of attention, Gansa says — particularly in the form of “tremendous opposition” to Danes as Mathison, a bipolar intelligence officer, and Damian Lewis as Nicholas Brody, an American POW she suspects of being a sleeper agent for the terrorist Abu Nazir.

“I don’t think anyone wanted me to play him,” Lewis laughs.

Lewis, of course, landed the role, and Gansa and company ultimately held off executives’ desire to cast Robin Wright or Maria Bello in the lead — arguing that the character’s bipolar disorder necessitated a younger actress, because by her 40s a person with the disorder would typically have devised a way to manage it, or not. Once production was underway, what swiftly emerged was the electric chemistry between Danes and Lewis — to the point that a key scene in the pilot was rescripted and reshot to take advantage of the dynamic, according to writer and executive producer Chip Johannessen. Gansa remembers his assistant imploring him to watch the dailies of an early scene: “It was so visceral and apparent on the screen that [it] wound up changing the course of the show,” he says. “We started writing to that in a way that we hadn’t necessarily expected to before.”

The resulting arc, in which Brody and Carrie mix an illicit relationship with mutual mistrust, helped make the series an object of intense fan interest. Season 1 earned “universal acclaim” from critics, according to the review-aggregation site Metacritic, and eventually won Emmys for drama series, lead actress, lead actor and writing for a drama series.

“The first season started airing as we were filming, so I got pretty direct confirmation just from people on the street,” Danes recalls. “Insane enthusiasm. People were literally running out of buildings and grabbing me and saying, ‘I’m obsessed with your show!’ It was hard to ignore the impact.”

For Patinkin, the confirmation came closer to home. A screening of the pilot episode at a party in the Hamptons led his own children to warn him that “Homeland” was about to be a very big deal: “They turned to me and they said, ‘You better be prepared that your private life is over.’”

‘Q&A’ & after

Though Brody’s abortive attempt on the life of the president of the United States in the Season 1 finale attracted more attention, the main characters’ romantic arc culminates in Carrie’s unbearably tense interrogation of Brody in the Season 2 entry “Q&A” — one of the finest hours of television produced in the last decade. (“I got the script and I went into pure panic, because it was 40 pages in one room,” says the episode’s director, “Homeland” executive producer Lesli Linka Glatter.) But “Q&A” is also the moment to which a number of “Homeland” veterans trace the series’ ensuing struggles: By the end of Season 3, scarcely two years after it was hailed as one of TV’s best shows, the New Yorker wondered, “Where Did ‘Homeland’ Go Wrong?”

“After we wrote [‘Q&A’], it became much more difficult to write the show,” Gansa admits, describing as “strained” a subsequent subplot in which Brody turns double agent, with Carrie as his handler. “It became really hard to tell as compelling Brody stories as we did before that interrogation episode, because now everybody was on the same page.”

Complicating matters was Showtime’s interest in continuing the relationship that had fueled its smash hit for as long as possible. The writers had seen dramatic potential in extending Brody’s arc, originally planned for one season, into a second. But extending it beyond that came at executives’ behest.

“I remember the guys writing the end of Season 2 with me dying and going to pitch it to Showtime and Showtime’s jaws hitting the floor and [them] saying, ‘What do you mean? Brody’s not going anywhere,’” Lewis says.

“Keeping that thing going yet another year was very much a studio/network negotiation,” Johannessen recalls. “They said, ‘We’ll pick you up for two more seasons if you agree to keep that relationship in play.’”

As writing “Homeland” became more challenging in the face of these constraints, so did watching it: With the air let out of Brody and Carrie’s relationship, Carrie and Saul on the outs and Brody’s daughter, Dana (Morgan Saylor), embroiled in teenage mischief — with Timothée Chalamet! — more appropriate to a family melodrama, critics and fans alike began to turn against the series. Its impressionistic main titles and Carrie’s crying jags even came in for satire via Anne Hathaway on “Saturday Night Live.”

Lewis blames the abrupt change to his character’s fate for the “improbable” situations and “narrative leaps” that followed — criticisms of which the writers were acutely, even painfully, aware. “It was flattering that they wanted to keep Brody around,” he says. “But I was also aware that I was the problem.”

‘We were always starting over’

The solution came in the Season 3 finale, “The Star,” in which Brody is hanged in Tehran for killing the head of Iranian intelligence — a decision made against the network’s wishes. “At that point, there was some begging that went on,” Gansa says. “‘Please don’t do this.’”

It also left the writers to face that most seductive, and terrifying, opportunity: the clean slate.

Enter “spy camp,” an annual meeting at Washington, D.C.’s City Tavern Club between the “Homeland” team and an array of current and former intelligence officers, State Department officials and journalists. (One year, Edward Snowden was among the speakers.) Both Gansa and Johannessen say that the conclave was crucial to the next stage of the series’ evolution.

Since the start of Season 4, “Homeland,” inspired by these marathon sessions with the trade’s top insiders, has metamorphosed into a slim, spry thriller structured almost like an anthology, with each 12-episode arc focused on a new challenge and set in a new locale: drone warfare in Pakistan, for instance, or ISIS sympathizers in Berlin.

At the start of the fourth season, Carrie, now the CIA station chief in Kabul, Afghanistan, green-lights a strike on a Pakistani wedding, killing dozens of civilians but not her intended target, Taliban leader Haissam Haqqani. In reprisal, Haqqani kidnaps Saul, creating a diversion for his real endgame: a devastating attack on the U.S. embassy in Islamabad. The season climaxes with a pair of the series’ strongest episodes, “There’s Something Else Going on” and “13 Hours in Islamabad,” a riveting, two-part indictment of America’s conduct of the war on terror that felt like “Homeland’s” return to form.

“The biggest triumph of the show, apart from the first season, was the fourth season,” Gansa says. “The show could have ended much more quickly if that season didn’t work.”

Though Season 4 constituted “proof of concept,” per Johannessen, this new narrative approach also forced “Homeland” to become even more nimble — shifting the focus to Berlin, ISIS and Russian interference in Season 5, and then to domestic politics and locations in Seasons 6 and 7.

“Usually, with series TV, it gets easier year by year. You have it dialed in,” Glatter explains, comparing the experience to making a pilot episode every year. “‘Homeland’ never got easier, because we were always starting over.”

While the success of Seasons 4 and 5 revived the series’ critical reputation, and may have stanched the flight of its fans following Brody’s death, the same period saw increased scrutiny of “Homeland’s” depiction of Muslims. Detractors called it “bigoted” and “Islamophobic,” Pakistani officials complained that it maligned a close U.S. ally, and graffiti artists hired to create background art for Season 5 wrote “‘Homeland’ is racist” in Arabic in a scene that made it to air. As if in response, the next two seasons turned their attention to Russian meddling, “the deep state” and the American far right.

“I think there was some validity to those criticisms,” Danes says. “It was unfortunate that we were a little too glib or a little too reductive in our portrayal of those characters, but I think our response to it was quick and sincere.”

Gansa agrees, adding that the criticisms “100%” made the series’ creative team more cognizant of the messages it conveyed about Muslims. “I thought that was great,” he says of the graffiti incident. “It was a nonviolent, subversive way of getting a message across.”

Still, the accusations of Islamophobia left a lasting mark on “Homeland.” According to Johannessen, two scribes set to join the writers’ room for the final season — one of Lebanese background and the other Iranian — dropped out at the last second, which he believes was a result of pressure from people in their communities not to support “Homeland.”

“The diversity of our writers’ room was not great. And we made an effort all the time to bring in writers, and we had trouble staffing,” Johannessen says. “By the time it’s maybe keeping you from getting people you want, that’s not good.”

Back in the U.S.A.

After filming consecutive seasons on location in South Africa (standing in for Pakistan) and Germany, Danes, Patinkin and the rest of the team were ready to come home. A discussion at that year’s spy camp about the practice of briefing the president-elect on national security issues inspired the New York-set Season 6, in which Carrie advises Sen. Elizabeth Keane (Elizabeth Marvel), newly elected president on an antiwar platform that antagonizes the intelligence community. And, as with a number of key moments in “Homeland’s” evolution, the timing of the series’ homecoming was serendipitous: The season premiered on Jan. 15, 2017, five days before the inauguration of President Donald Trump.

Though Gansa, Johannessen and Glatter maintain that Keane was not specifically modeled on Trump or his opponent, Hillary Clinton, the real-life campaign cast an unavoidable shadow over Season 6 — one that resulted, yet again, in exasperated critics wondering what went wrong. They were not alone in the sense that the series had, for once, been outflanked by events.

“There was definitely a feeling like, ‘You cannot match the craziness of this situation, so you just have to stay away from it,’” Johannessen says, citing HBO’s “Veep” as another series to face the same problem.

“That was the hardest moment for us, actually — that period during the election, when we were waiting to see who was going to actually come into office,” Danes recalls of developing the season. “[The writers] were really stymied. I felt them to be creatively frustrated because of that lack of direction.”

Both Keane’s character and the “deep state” machinations that propel the season’s plot are an awkward fit, too far from the facts to seem prescient and too near to feel original. Even so, certain aspects of the production dovetailed eerily closely with events on the ground.

“There was a moment that we were staging a protest outside of the Intercontinental Hotel in New York,” Glatter says. “It was probably 300 people with signs saying ‘Not my president.’ Meanwhile, there was a rally at Trump Tower with signs saying ‘Not my president.’ And people walked into our rally, normal people, going, ‘What’s going on here? What rally is this?’ And we were shooting ‘Homeland.’ That was very discombobulating, to say the least.”

An ‘elegant’ ending

As “Homeland’s” penultimate season began, with near self-parodic bluster, now-President Keane has imprisoned hundreds of members of the intelligence community in retaliation for an attempt on her life. Absent longtime ally Peter Quinn (fan favorite Rupert Friend), who sacrifices himself to save her and Keane at the end of Season 6, Carrie must take the fight to the woman in the Oval Office all by her lonesome. By the seventh season’s brilliant end, with Keane’s resignation and our heroine released to Saul after an extended stint in Russian captivity, “Homeland” returns to its foundational bond — and recaptures the taut terms of its finest hours.

It also sets up the final season’s “elegant” conceit, as Danes describes it. Though Carrie’s bipolar disorder is a running theme throughout the series, coming in and out of focus as her circumstances change, it returns to the forefront after her stint in prison, during which she has been denied her medication. The possibility that she has revealed sensitive information while under such duress, and does not remember it, leads some in the intelligence community to question her allegiance.

Or, as Danes puts it, “Carrie becomes Brody.” This effect is underscored by the title sequence, which combines sounds and images from the first seven seasons, and the season’s plot, which Gansa says is designed in part to tie up loose ends from Season 4, including the fate of Haissam Haqqani. Very purposefully, in other words, the series’ closing arc conjures the feeling of vintage “Homeland.”

The list of TV series to survive long enough, in enough configurations, for such a phrase to be applicable at all is vanishingly short. Certainly, none in the past decade have swung quite so wildly from the ridiculous to the sublime as “Homeland.” But the series’ end has a valedictory quality: As perhaps the last of the “Golden Age” dramas to go off the air, “Homeland” is an emblem of a form — the ongoing, “prestige” drama — that appears to be in decline.

In “Homeland’s” case, it’s not for lack of material; if anything, as we approach 20 years of the war on terror, the series’ continued relevance has become an objective correlative of the conflict’s endlessness. As Patinkin suggests during the course of our conversation, by turns tearful at the significance of the journey and relieved by its conclusion, “Homeland’s” ability to evolve in tandem with its troubled times is also what left those involved too drained to continue.

“It could go on forever, a show like this,” he says. “If you can endure it.”

‘Homeland’

Where: Showtime

When: 9 p.m. Sunday

Rating: TV-MA (may be unsuitable for children under the age of 17)

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.