Review: Goya gave Frankenstein’s monster his Hollywood face. Now this museum shows the artist’s larger power

- Share via

If you’re exhausted by all the criminality, outrageous racism, gaslighting, antediluvian misogyny, pedestrian hatreds, cruel religiosities, fascist violence, rank cowardice and power-mongering greed that have characterized our national political life since at least 2015, I recommend a visit to the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena.

Seriously.

There you will find a bracing refusal of all such things from another, similarly rancid era 200-plus years ago, produced by one of the paramount artists to emerge from Enlightenment Europe. The exhibition “I Saw It: Francisco de Goya, Printmaker” might not fix things today, but at least you will find solace in knowing that survival is possible.

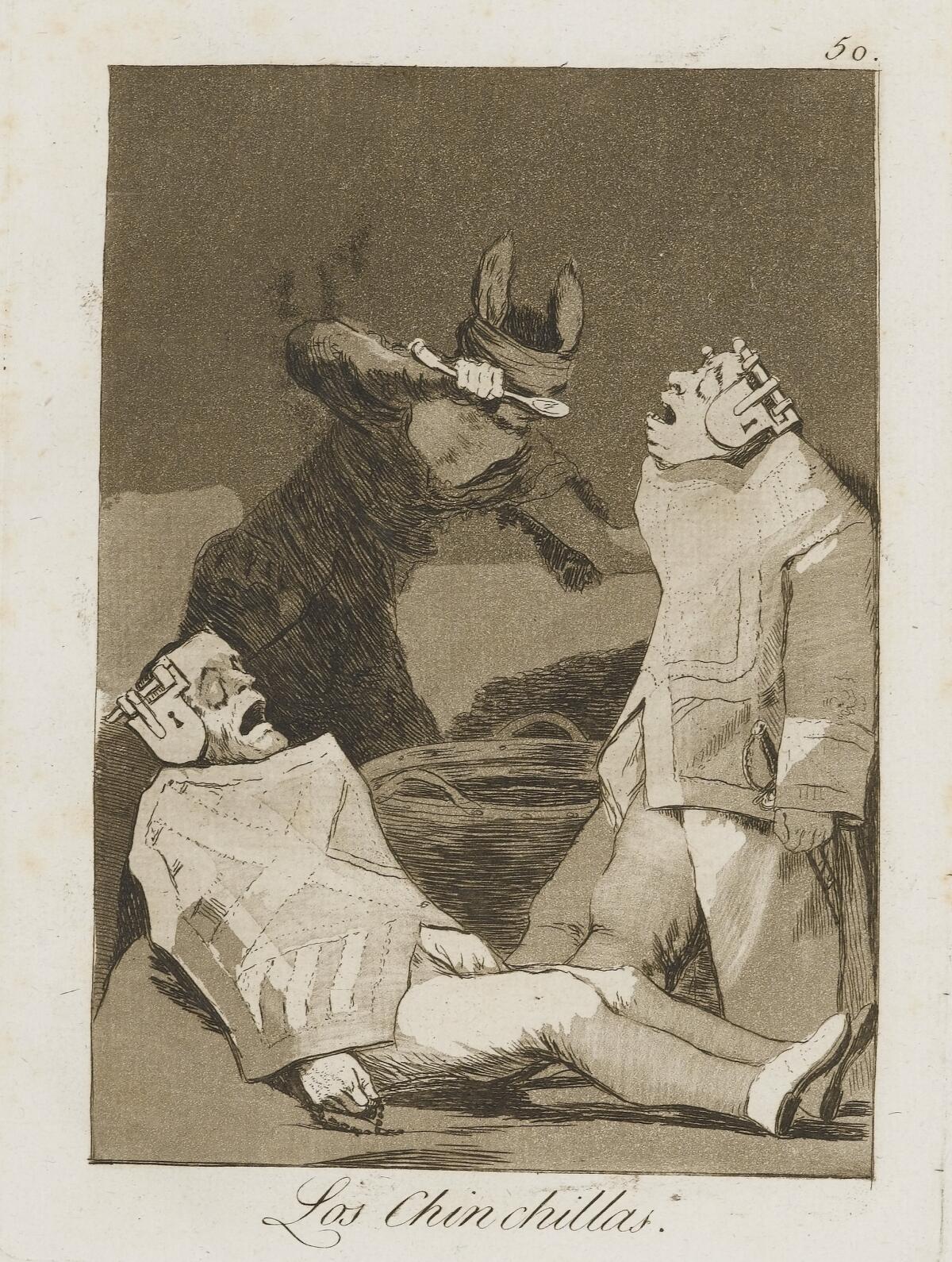

As a bonus, not one but three versions of “Los Chinchillas (The Chinchillas)” are on view. Self-shackled nobles, bound in family crests with ears padlocked against learning, are shown dining on a big spoonful of ignorance dished out by a donkey-eared being. That’s the etching that actor Boris Karloff and makeup designer Jack Pierce turned to for inspiration in creating the look of their Frankenstein movie monster. Fitting horror in 1799, 1931 and 2024.

The show is satisfyingly large. For the first time ever, the Simon museum is exhibiting its extraordinary holdings of all four of Goya’s main print series. In fact, according to press materials, no museum on the West Coast has ever shown the four together in their full sweep — perhaps because of the total size, which strains the usual limits for an ordinary show. But these are not ordinary times, and there is a lot to see and take in.

Displayed are the 80 plates in “Los Caprichos (The Caprices),” 82 in “Los Desastres de la Guerra” (The Disasters of War), 33 in “La Tauromaquia” (Bullfighting)” and 22 in “Los Disparates (Nonsense or Follies).” The etchings were made over a tumultuous quarter-century between 1799 and 1823, when Goya was a mature artist, and the vast Spanish empire was coming apart at the seams. He started them in his early 50s and finished in his late 70s. (Born in Aragon in 1746, Goya died at 82 in self-imposed exile in Bordeaux, France.)

In addition to those 217 etchings, the museum has added a number of trial and working proofs as well as hand-colored editions. One display case, for example, includes a bound first-edition book of “Los Caprichos,” open to Plate 35. “Le descañona (She fleeces him)” mocks a goofy aristocrat in a brothel swooning as he is being shaved by a comely prostitute. (Take “shaved” any way you’d like, from barbering to robbery.) Adjacent are three single sheets: a 1799 first impression, a somewhat darker second edition printed posthumously (around 1855) and another 1799 impression that was hand-colored almost two decades after printing to enhance the imagery’s sensuality, heighten the drama and — with luck — improve chances for a sale.

The exhibition has a number of such intriguing juxtapositions, which amplify the unique characteristics of the printing medium that Goya meant to exploit. His paintings had mostly been for grandees, Goya’s patrons at the Spanish court, but his prints were instead about them — and about ordinary Spanish people. His flamboyant portrait painting of the Marqués de Caballero, acquired last year by the Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Gardens in San Marino, is both a dazzling likeness of the self-made man and a slyly buried take on the court official’s personal grandiosity, thanks to the painterly fireworks in the rendering of his overweening wardrobe. In the prints, Goya took the gloves off.

L.A.’s most popular art museum can be overwhelming. Critic Christopher Knight offers his favorites: must-see paintings, sculptures and more, and what to know about each.

Among the most compelling additions is the public debut of working proofs for “The Disasters of War,” the justly famous chronicle of unspeakable butchery, one of just two such sets known to exist. The differences between what the proofs indicate Goya originally intended and what finally appeared in the bracing first edition, which wasn’t printed until 35 years after his death, can surprise.

Take Plate 7, a scene of a woman who has taken command of a military cannon, dead bodies piled beneath her feet. It’s gloomy, melancholic and vaguely desperate in the published edition, where the sky has been grayed through aquatinting and the overall tonal sharpness tamped down.

In the working proof, however, Goya left the paper clean for the sky, its blazing whiteness drawing a stark visual contrast with the murky machinery of death below. The inky black upper body of the woman is now silhouetted against pure whiteness, while her long white dress is set against the blackened wheel of the cannon. (That layering made me think of the so-called Catherine Wheel, a favorite of Baroque painters who tagged the torture device in which martyred St. Catherine of Alexandria was torn apart.) Visually, black against white and white against black animate the dramatic central figure, distinguishing her from the inanimate corpses that lift her up, like a morbid human pedestal.

Titled “Que Valor! (What courage!),” the working proof’s image is stirring rather than dismal, its grim aura of inescapable doom leavened with the inspiration of powerful resistance. The battle story was an actual event in which a woman named Augustina Zaragoza manned a cannon against Napoleon’s army in the epic 1808 siege of Saragossa, capital of the Aragon region. Among the dead on whom Augustina stood was her lover. Goya no doubt read about the “Maid of Aragon,” the instantly mythologized heroine from his home region in Spain, in newspapers and pamphlets. Several years later, when he began the project to chronicle war’s horrors, he rose to the occasion.

As an artist, Goya ranks as the virtual definition of social consciousness. Official court painter to not one but two kings of Spain, terrorized nonetheless by the Roman Catholic Church’s brutal Inquisition, he navigated the dangerous shoals of a disintegrating empire that had made a select aristocracy fabulously rich, and where one in every 50 Spaniards hid behind righteous sanctity as a priest, nun or friar. It was anything but easy, but it did yield close-up insights into the complexities around humanity’s worst features.

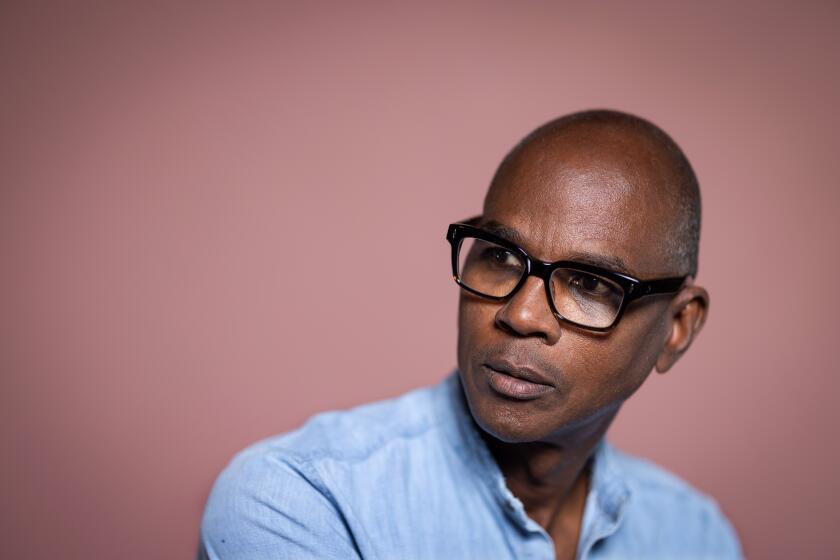

Mark Bradford ranks among the top artists to have emerged in — and defined — American art in the 21st century. His work demonstrates the power of abstraction.

The show, organized by Simon museum curator Gloria Williams Sander, devotes a separate space to each of the four series. Work is installed in royally colored rooms — painted red, green, gold and purple — in the sequence of plates the artist intended. Occasionally, the order breaks to insert multiple examples that illuminate the printmaking process. There is no catalog (the museum published a scholarly book on all the Goya works in its collection in 2016), but the informative wall texts and object labels are well done.

“Los Caprichos” begins with unsparing social observation, including the destructive avarice of the Catholic Church, which might put you in mind of today’s predatory Christian nationalists. The narrative pivots halfway through to supernatural allegory, with “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters,” arguably Goya’s most widely known print, in which flocks of birds and a cloud of bats swirl in the night. The final etching, “Ya es hora (It is time),” is a screeching dance of four grotesque clerics who throw up their hands in a frenzy — sleeping reason’s worldly monsters identified. (I could swear one of them is the spitting image of Franklin Graham.)

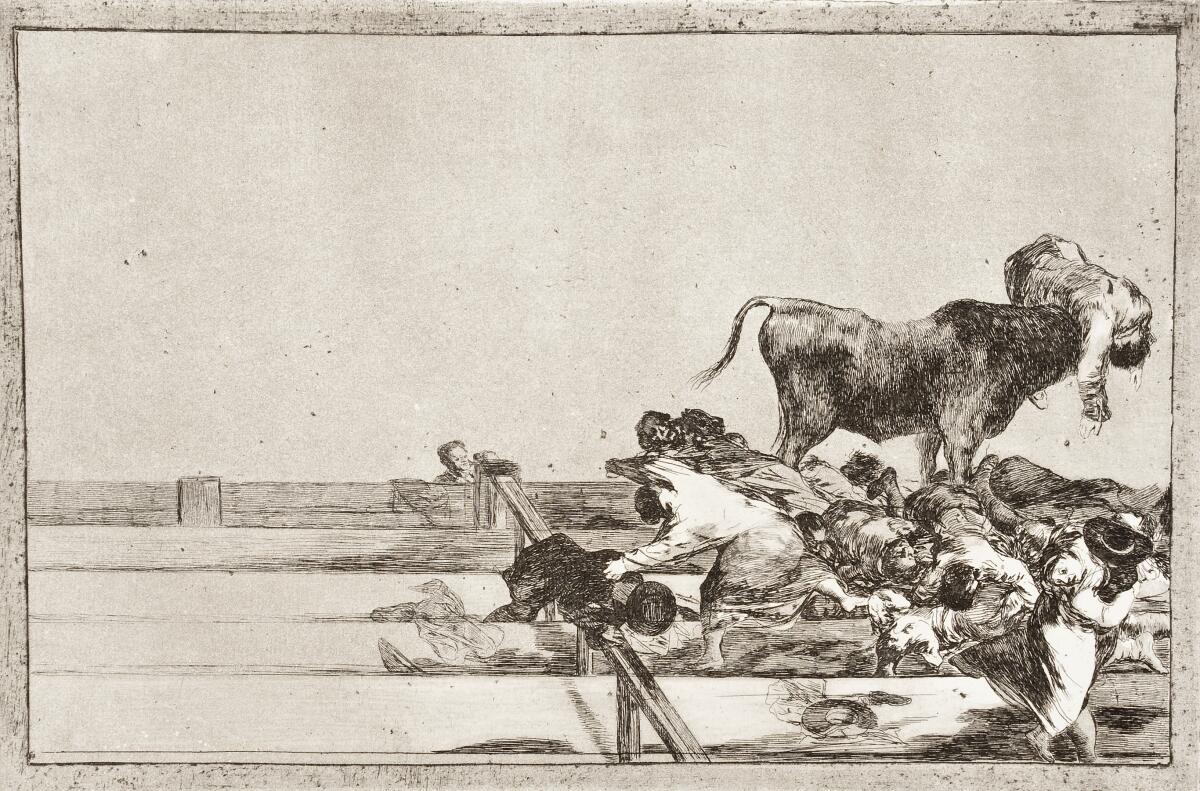

Inside the grim room for “The Disasters of War,” a free-standing space features the bullfight prints (some inspirations to Picasso). Its chronology begins with the ancient practice of hunting bulls in the wild for meat and skins, then traces the hunt’s evolution as sport with the emergence of celebrity toreadors in a theater of cruelty and courage.

One extraordinary plate records a purported real-life disaster when a bull leaped into the stands and gored a town’s mayor to death. Goya divided the sheet into halves: At the right, the dense chaos of catastrophe is packed in, while at the left the bull ring’s stands are virtually empty, fans having fled. The bifurcated composition, which relies on a pictorial void for its comparative punch, is shockingly modern.

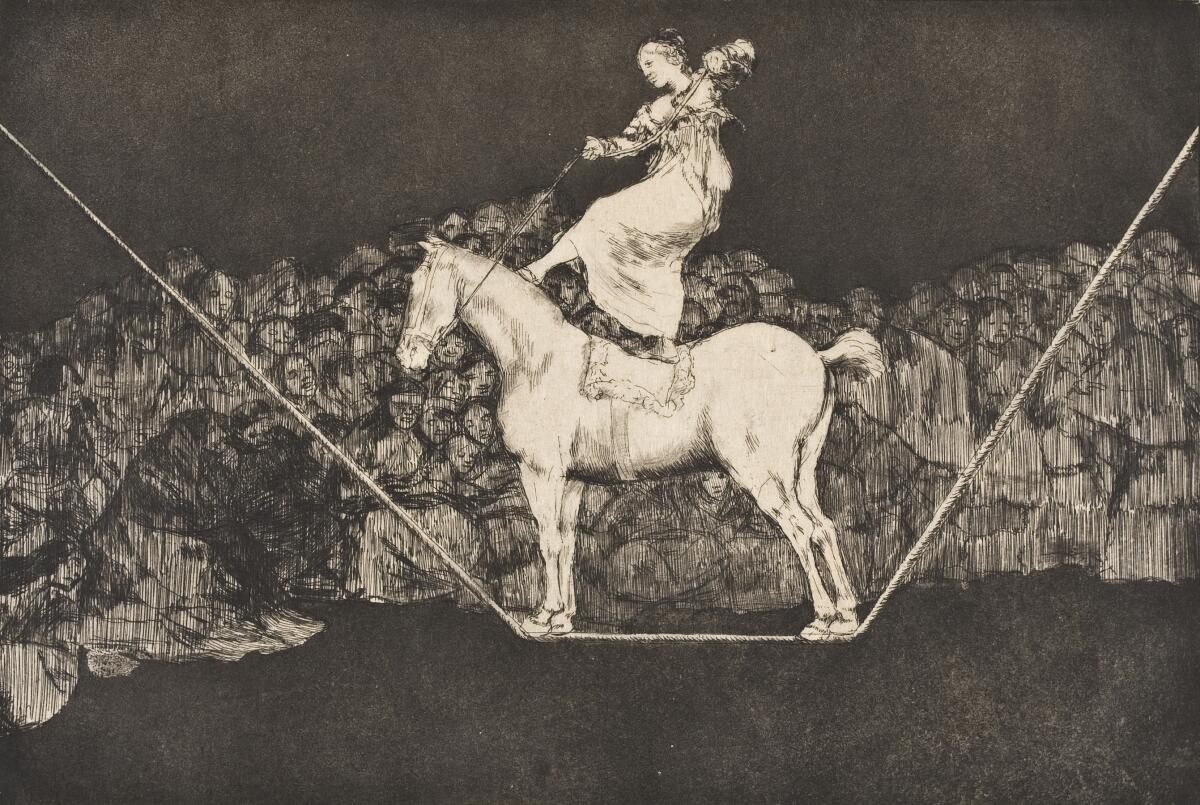

Lastly, the follies and dark satires of “Los Disparates,” sheets considerably larger than the rest, suggest life as a raucous carnival of nearly inexplicable mystery. Produced during the return of absolute monarchy under King Ferdinand VII — el Rey Felón, as the corrupt and reactionary sovereign who abolished the nation’s hard-won liberal constitution was soon known — it flays the disastrous social shift desired by much of the war-weary populace. (When beaten down enough, a public sometimes yearns for an all-powerful autocrat to take the reins.) The stunning picture of a woman dancing on the back of a horse impossibly balanced astride a narrow tightrope is a historic exemplar of the diversionary power of bread and circuses. As a mesmerized crowd gapes, our own cartoonish media landscape today comes into focus.

As many museums do now, this bracing show of historical achievement is joined by a modest separate installation, “Modern Artists Respond to Goya,” with more recent works. Current relevance is sought for old art (as if Goya needs help). But in this nuanced context, something like the satirical screenprint of Jacqueline Kennedy by Andy Warhol just doesn’t cut it. Yes, it’s also a print; and yes, the photographic image taken at the funeral of her murdered husband derives from a national tragedy connected to the government. But complex, incisive social critique is not at all what Warhol was after.

“Jackie II” (1966) repeats a stock photograph of mourning, but it is a lament for intransigent New York art culture. Warhol’s screenprint pictures Mark Rothko’s reigning dictum that “only that subject matter is valid which is tragic and timeless,” while giving a commercial platform to images of women, Willem de Kooning’s Abstract Expressionist trademark. In a nutshell, that’s the widowed Jackie Kennedy (and suicided Marilyn Monroe too).

The cloistered art establishment was keeping Warhol out, so he found a way in. Goya wasn’t in a remotely similar situation. Kings were his patrons, and his prints reported what he discovered from being in proximity to power. The small contemporary show can’t help but feel superfluous by comparison to the absorbing Goya of “I Saw It.”

'I Saw It: Francisco de Goya, Printmaker'

When: Thursday-Monday, through Aug. 5

Where: Norton Simon Museum, 411 W. Colorado Blvd., Pasadena

Admission: $15-$20; youths 18 and younger free

Information: (626) 449-6840, nortonsimon.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.